By John R. Barrows

Editor’s note: Most of what we present here about hero pilot Bill Frayne’s wartime exploits is owed to Steve Ruffin and his exhaustive work with original source records as published in Over the Front, the official publication of The League of World War I Aviation Historians. Colonel (Dr.) Ruffin served as Managing Editor of Over the Front from 2007 – 2010. Before that, he served as an issue editor. He is a retired U.S. Air Force officer with a lifelong interest in World War I aviation. He has traveled extensively in Europe, locating important WWI aviation sites, and he has spoken and written on a variety of aviation topics. Monmouth Timeline is also grateful to Mike O’Neal, a member of the board of trustees at the Golden Age Air Museum in Bethel, Penn., who also provided information and photographs for this story. The Golden Age Air Museum, just over two hours away from Monmouth County, offers a wide variety of hands-on and close-up experiences with World War I aircraft, and for anyone interested in or curious about New Jersey aviators in the first world war, this is a must visit. Mr. O’Neal, besides being the foremost historian with respect to New Jersey WWI aviators, is a published author, editor of Over the Front, and an amazingly talented artist to boot.

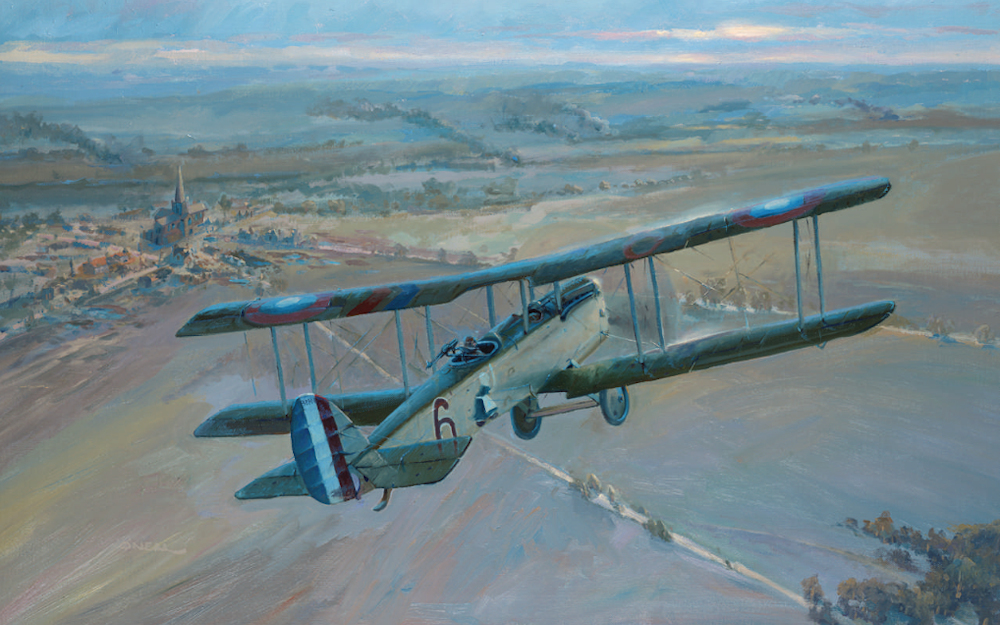

On October 17, 1918, 2nd Lieutenant William D. Frayne was the pilot at the controls of a DeHavilland DH-4 “Liberty Plane” over France. The DH-4 was a two-seater outfitted with four machine guns, but was mostly used for reconnaissance observation, as it was on this occasion. Frayne and observer 2nd Lt. Howard C. French were part of the 50th Aero Squadron out of Remicourt Aerodrome, a temporary World War I airfield located in the Marne region in northeastern France near Belgium.

The warplanes of this era — barely a decade after the Wright Brothers first proved heavier-than-air manned flight was even possible — were extremely dangerous to operate, and those serving in the fledgling U.S. Army Air Service experienced among the highest casualty rates of any arm of the U.S. war effort in World War I. These planes were typically made of wood frames covered with fabric coated in a flammable substance called “dope,” held together with wires and glue. Pilots and observers had neither heat nor pressurized cabins, and so performed their duties while exposed to extremes of cold and wind. The guns mounted on such aircraft routinely malfunctioned, making crews sitting ducks for enemy fighters. Engines were unreliable as well, and the Allies at this time still did not offer air crews parachutes. Ground troops, most of whom were unfamiliar with aircraft, tended to shoot at anything in the air regardless of whether it was friend or foe. They were sometimes also reluctant to cooperate with aerial observers who needed signals from the ground to make precise notes. And if anything went wrong in the air, survival was a slim prospect.

Imagine the horror of those on the ground who noticed that Frayne and French’s aircraft had suddenly caught fire while flying at 2,000 feet. French’s flare gun had accidentally discharged, and the airplane’s fuel tank, located in the space aft of the pilot and forward of the observer, was now in flames.

It might have been a fairly simple matter for Frayne to immediately and directly bring his plane in for an emergency landing, but flying in a straight direction would blow the flames of the burning fuel tank right at French, who had no place to go to evade the smoke and fire. The tank could explode at any moment.

Onlookers saw Frayne take the extra time and extraordinary risk of bringing his aircraft down in a side-slip motion that kept the wind blowing the flames off to one side and then the other, rather than in a straight line.

According to Steve Ruffin, an author and aviation historian who has extensively studied the 50th Aero Squadron, “a forward or side slip allows a pilot to quickly lose altitude without gaining airspeed. It would normally be used to rapidly descend during final approach, in cases where the aircraft is too high and would otherwise overshoot the runway. It is also necessary for landing in a crosswind. It is not particularly risky — providing your airplane is not on fire, as was Frayne’s — but it does require some skill. It is accomplished by crossing the controls — left stick with right rudder or vice-versa, depending on the wind direction.”

Frayne’s actions required bravery and great presence of mind. He was able to bring the plane down onto an open field; he and French jumped out while the plane was still rolling, and just seconds later, the fuel tank exploded. Frayne and French were both mostly unharmed, and were back flying again in just days.

According to Ruffin, “It was obvious to everyone that Bill Frayne had risked his own life in the attempt to save that of his comrade. And, owing to this harrowing experience, the squadron instituted a new policy of carrying Pyrene fire extinguishers in the rear cockpit going forward. This would prove within just the next week to be a very wise policy.”

Frayne was awarded the Army Silver Star, one of the highest awards for valor following the Medal of Honor and the Distinguished Service Cross. His citation reads:

By direction of the President, under the provisions of the act of Congress approved July 9, 1918 (Bul. No. 43, W.D., 1918), Second Lieutenant (Air Service) William D. Frayne, United States Army Air Service, is cited by the Commanding General, American Expeditionary Forces, for gallantry in action and a silver star may be placed upon the ribbon of the Victory Medals awarded him. Second Lieutenant Frayne distinguished himself by gallantry in action while serving with the 50th Aero Squadron, American Expeditionary Forces, in action on 17 October 1918, in safely piloting his machine to the ground after it had caught fire.

GENERAL ORDERS: GHQ, American Expeditionary Forces, Citation Orders No. 2 (June 3, 1919)

Bill Frayne: Early Years

According to his Army service card, William David Frayne was born October 22, 1899, in Middletown, Connecticut. This date of birth is incorrect, as Frayne noted in three different census reports that he was born in 1889. He studied at Cornell, graduating in 1913 with a degree in mechanical engineering.

When hostilities broke out in Europe in 1914, America clung to neutrality, but despite the likelihood that the U.S. might be drawn into the war, little was being done in the way of military preparation. A few visionaries, seeing the role of aircraft being used by both sides in the escalating war, saw the need to establish aviation schools and begin the process of grooming American men to be pilots. Prior to this, some Americans with any kind of flight experience had already been volunteering to serve as pilots for the French, as well as the British, in military aviation units. These volunteers risked everything to help the Allies. With the U.S. maintaining its neutrality, the government issued warnings that anyone who went overseas to take up arms on behalf of another country could be stripped of their citizenship. And yet, this did little to dissuade those who were committed to joining in the fray. One such man was Charles Maury Jones of Red Bank, who was a prominent wealthy socialite of Monmouth County before the outbreak of war. Jones risked losing his family fortune, his citizenship, and his life, by becoming a pilot for France. But the net effect of his and the service of other such volunteers was to inspire hundreds of men to enlist.

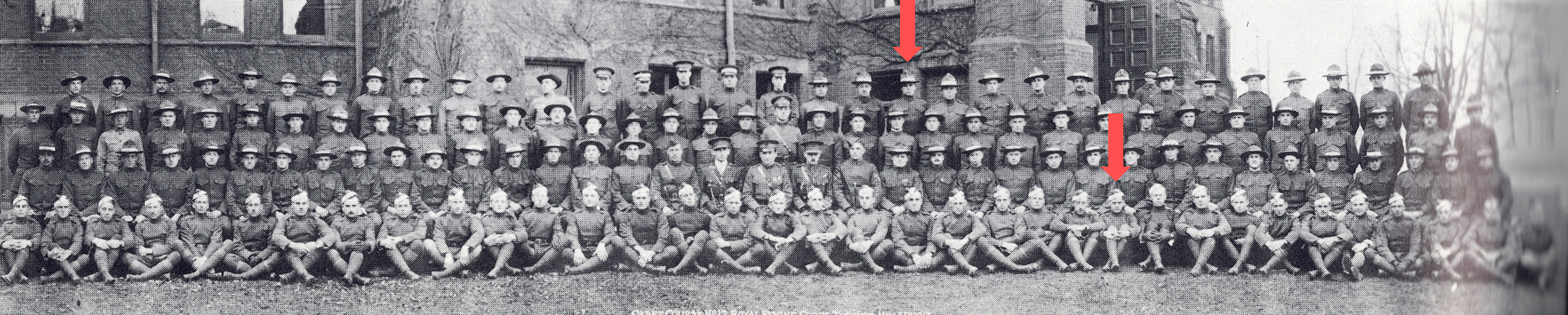

Bill Frayne was likely one of these men, inspired by the tales of derring-do of units like the famed Lafayette Escadrille squadron, with images of dashing pilots on newspaper front pages across the U.S. According to Ruffin, “In 1917, he was accepted into the U.S. Army aviation program and sent to one of the new schools of military aeronautics, which were ground schools being established at major universities throughout the country. After successfully completing this, he traveled to Canada as one of the so-called ‘Toronto 300,’ the first Americans to receive flight training conducted by British and Canadian instructors.”

Another member of the Toronto 300 was Theodore D. “Ted” Parsons of Little Silver. In fact, Parsons was with Frayne at the RAF school in the same class, Cadet Course No. 17, which graduated November 5, 1917, so they clearly must have been acquainted during this time. Parsons went on to be a celebrated New Jersey Attorney General, and in an interview late in his life, said he had a picture in his hallway that “recalls the Liberty DH-4 he had tested in France for famed combat pilot Bill Frayne.” Parsons was a very public figure living in Little Silver, but it is not known if he and Frayne reconnected during their postwar years.

After Canada, Frayne went to Fort Worth, Texas, for further training. According to Ruffin “as was typical, he [Frayne] was temporarily assigned to a training squadron (probably the 22nd) until receiving his operational assignment. He first landed in England, where he received additional training.”

When ready, Frayne and others were transferred from England to France, where he and six other pilots from his group joined the newly formed 50th Observation Squadron, flying the DeHavilland DH-4 “Liberty Planes.” The 50th was a part of the 1st Observation Group, along with the 1st and 12th Aero Squadrons. Squadron responsibilities included “visual reconnaissance; surveillance of enemy artillery activity and fugitive targets; infantry contact patrols, adjustment and control of fire of Divisional Artillery; alert planes for special missions for Division and Corps Commander; and planes for protection for photo missions of 1st and 12th Aero Squadrons.” Frayne initially served as a flight instructor teaching the newer arrivals all the ins and outs of the notoriously troublesome DH-4.

Leaders of the 50th chose the “Old Dutch Girl” as their squadron insignia, based on a logo made famous by the popular cleaning agent, “Old Dutch Cleanser.” The product’s slogan in those years was “Chases Dirt.” It was selected to signal the 50th Aero’s intention to “clean up the Germans.”

Frayne’s abilities as a pilot must have been evident from early on, as he and French were the very first crew of the 50th to see action over enemy lines.

The Lost Battalion

On October 2, 1918, about 550 men of the U.S. 77th Infantry Division launched an attack into the Argonne Forest in France, against the mostly German Central Forces. The 77th believed they had other Allied units protecting their flanks, but those units were delayed, and the 77th found itself completely surrounded, cut off from the main group, and dangerously short on supplies, food, and water.

Over the next six days, nearly 200 men were killed in action and approximately 150 went missing or were taken prisoner. This being an era before field radio sets were viable, couriers were sent to try and sneak through the enemy lines and reach Allied command with a plea for help; they were all either captured or killed. Attempts were made to resupply the troops by air, including efforts by the 50th Aero Squadron. Bill Frayne was among the pilots attempting these dangerous missions. But commanders on the ground were relying on older means of communication.

The most effective means of long-distance wartime communication in that era involved the use of homing pigeons, a system developed and enhanced to a very high level of efficacy by the U.S. Army Signal Corps at Fort Monmouth. On October 4, a pigeon was sent with a message that unfortunately included inaccurate location coordinates, which precipitated an Allied artillery bombardment of friendly fire on the beleaguered 77th. Two pigeons were shot down by the Germans, who knew exactly what they were shooting at. A third, named Cher Ami, was given another message and sent off. After several seconds, he was shot down but soon took flight again. Cher Ami arrived back at his loft at division headquarters, 25 miles to the rear, in just 25 minutes. He had been shot through the breast, blinded in one eye, and had a leg hanging only by a tendon, but he was able to deliver this message:

We are along the road paralell [sic] 276.4. our artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heavens sake stop it.

Cher Ami became the hero of the 77th. Army medics worked to save his life. When he recovered enough to travel, the now one-legged bird was put on a boat to the United States, with General John J. Pershing seeing him off. Cher Ami was awarded the Croix de Guerre Medal with a Palm Oak Leaf Cluster for his heroic service in delivering 12 important messages in Verdun. He died at Fort Monmouth on June 13, 1919, from the wounds he received in battle.

Meanwhile, on October 5, the 50th sent out four aircraft—two in the morning and two in the afternoon—to drop messages onto the last reported location of the entrapped men. They also carried with them all the chocolate and cigarettes they could scrape together to drop to the doughboys below. Visibility was poor in the foggy drizzle, and the crews were unable to deliver their supplies to the exact location. This was a history-making event—the first attempt ever to resupply a ground unit from the air—but it was not successful. According to Ruffin, it is now generally accepted that none of the messages or supplies dropped by the airmen of the 50th Aero Squadron were ever received by the men pinned down by enemy gunfire on the ground below. As Ruffin points out, these crews were being asked to accomplish something wholly unprecedented:

- Fly at treetop level into the teeth of a concentrated enemy force with hundreds of enemy guns leveled at them;

- Locate a tight group of men hiding below in a hazy, over-grown ravine, who were—as it was later shown—200 yards east of where they said they were, and who were doing their level best not to be seen; and,

- Drop packages of supplies from the open cockpit of a speeding airplane with surgical accuracy, a feat that had never before been accomplished, or even practiced.

“On October 6, from daybreak until dark, one mission after another—13 in all, that day—took off in support of the Lost Battalion,” said Ruffin. “Some of these flights took baskets of carrier pigeons, each of which was dropped gently with the aid of approximately eight small parachutes taken from parachute flares. By day’s end, a thousand pounds of supplies and three baskets of pigeons had been dropped. Where they fell was anyone’s guess, however.”

How dangerous were these missions? Three planes of the 50th were shot down that day. The third plane was piloted by 2nd Lt. Harold E. Goettler, with his observer, 2nd Lt. Erwin R. Bleckley. “It was their second mission of the day to try to locate and supply the men of the Lost Battalion,” said Ruffin. “They made their way to the purported location of the pocket of men and began flying back and forth, parallel to the lines at very low altitude, trying to pinpoint where to drop their supplies. During this entire 20-minute period, they drew continuous ground fire from both German and French troops below, the latter of which were apparently unfamiliar with the American Liberty Plane. Finally, Goettler was hit in the head by an explosive machine gun bullet and instantly killed. The airplane, with a still-uninjured Bleckley in the back seat, suddenly turned towards the south, and dove into an open field just to the southwest of the town of Binarville. Bleckley was thrown clear of the crash but sustained internal injuries and died on the way to the hospital.

On November 15, 1922, Goettler and Bleckley joined flying ace Frank Luke, Jr. as the only U.S. Army Air Service officers to receive the Medal of Honor for actions performed during World War I. It was not until 1930 that Capt. Edward V. Rickenbacker, America’s “Ace of Aces,” joined their ranks, when his medal was finally approved.

Finally, one of the planes of the 50th sighted a signal on the ground that indicated the true location of the Lost Battalion. They then flew over to division headquarters and dropped a message with the critical information. Later that day, a ground attack was launched, based on these coordinates, and at 6:00 p.m. what was left of the decimated Lost Battalion—194 men from an original cadre of nearly 550—was rescued.

The heroic effort put forth by the squadron was noted, and on November 10, one day before the Armistice went into effect, Frayne was promoted to 1st Lieutenant. All told, Frayne was a pilot on 17 missions, accounting for 29.5 hours of flying time. Lts. Frayne and French had the distinction of making the first flight over the lines for the 50th Aero Squadron, and they also made the last flight for their unit a couple of days before the armistice. According to Ruffin, the legacy of the 50th Aero Squadron is:

They made history even though it was ‘only’ an observation squadron with no famed flying aces.

Bill Frayne Postwar Life

According to his veteran’s bureau card, Bill Frayne was discharged on February 20, 1919. He listed his address as 506 W. 111th Street in the Riverside Park neighborhood of New York City. The card also listed an address in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

During this time, 1919-1920, the commander of the 50th, Daniel Parmalee Morse, wrote a history of his squadron, and in his introduction, gave special thanks to Bill Frayne:

Much credit is due “Bill” Frayne for his help in writing the log and operations, as much of his composition has been included without change.

DANIEL P. MORSE, JR. New York City, January, 1920.

In this book, Morse states that, in fact, Frayne had been denied a commendation for his heroic action, as it was “not in the face of the enemy.” Some of the official Army records are missing, as are a great many military records, so it may be impossible to know for certain what is behind this discrepancy (On July 12, 1973, a fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis destroyed approximately 16-18 million Official Military Personnel Files. Approximately 80 percent of personnel records for Army personnel discharged November 1, 1912 to January 1, 1960 were permanently lost).

But, one explanation seems plausible: Frayne and Morse were both discharged in February of 1919. Frayne’s citation is dated June 3, 1919, more than three months later. Morse was a resident of New York City, which Frayne also listed as his address when discharged. It is possible that Frayne and Morse collaborated on their unit history while things were fresh in their minds, after they were discharged, and Frayne’s citation came either after the book had gone to print, or was simply overlooked by Morse as he completed the work. What is certain – and most important – is that Frayne did indeed win the Silver Star.

In the April 1920 census for Pittsburgh’s Ward 7, William D. Frayne is listed as a “lodger,” age 29, from Connecticut, occupation “Mechanical Engineer” and under Industry it reads, “Machine Shop.” Interestingly, the next person listed in that census is another lodger, named Leroy Morris, from Pennsylvania, age 33, who listed his occupation as “Mechanical Engr” and for industry, “Consulting.” It seems likely that Frayne and Morris were involved together in some way, but this is conjecture.

Later that year, a notice in the Buffalo Evening News announced that “Mr. and Mrs. F. J. Hussey of Grand Island, N.Y., announce the marriage of their sister, Helen Betty Hoff, to Mr. William David Frayne of New York on August 6.” All other references to Helen Frayne give her middle initial as E, so we may deduce her correct middle name was Elizabeth.

In July of 1926, the Fraynes bought a house from Henriett Jenkinson on Shrewsbury Way in Sea Bright, a house they owned for the rest of their lives, although it appears that Bill Frayne traveled a lot as part of his career pursuits, sometimes with Helen.

For example, in the 1930 census for Brooklyn’s First Ward, William D. Frayne is listed, age 40, from Connecticut, occupation “engineer” in the oil industry; Helen is listed immediately after.

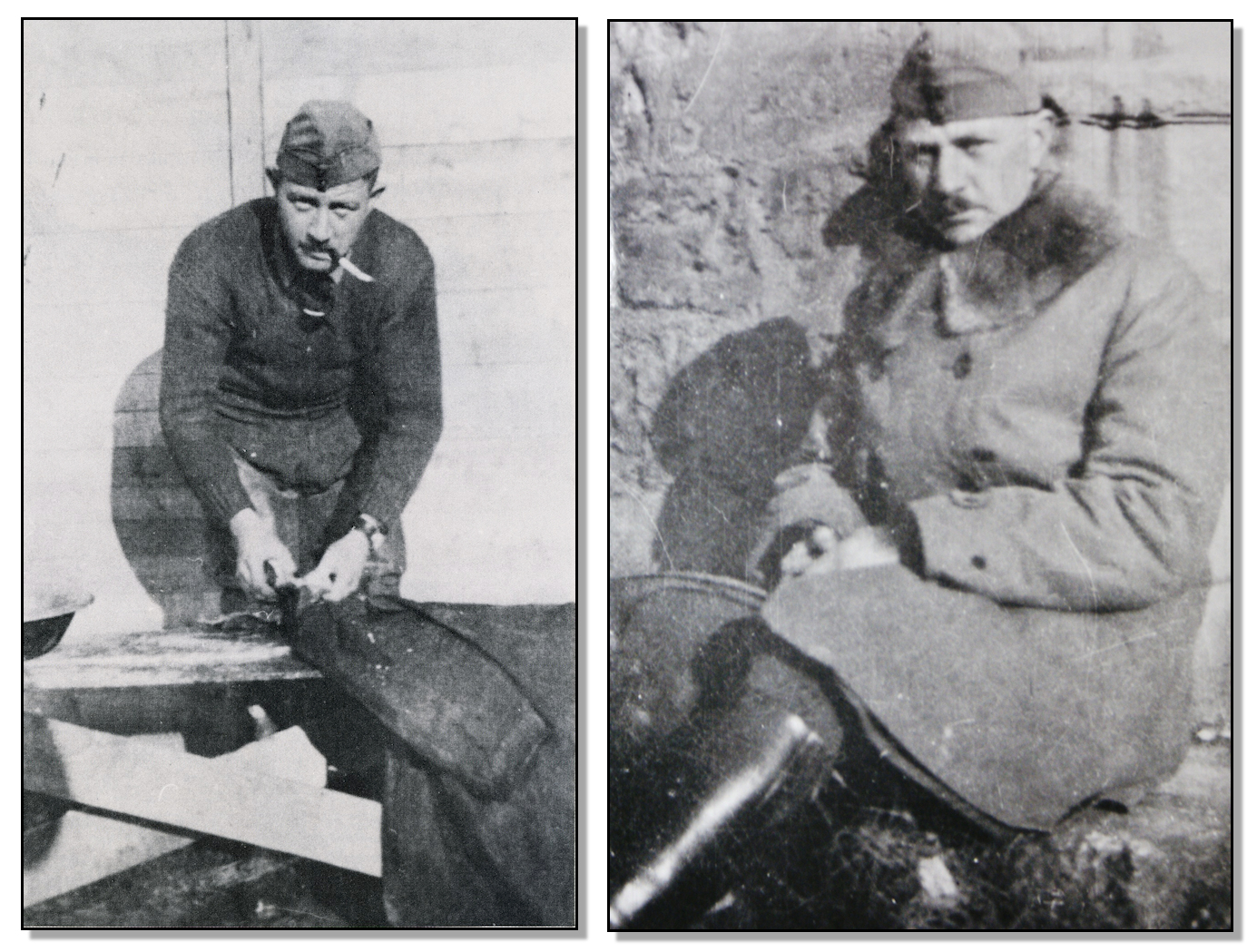

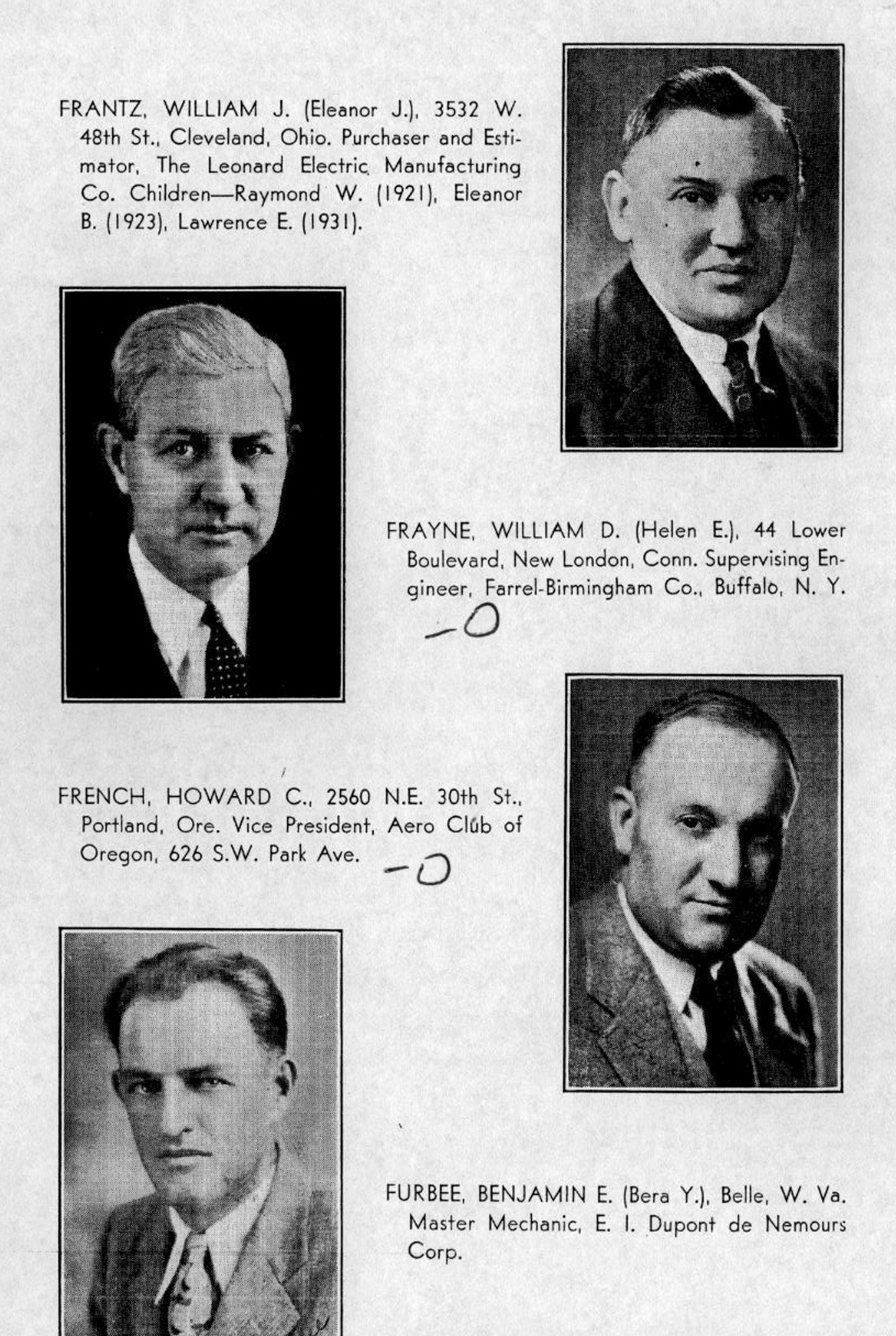

In 1936, the Harrisburg (Penn.) Evening News ran a story about a reunion of the 50th, and noted the following: “Native Pennsylvanians, who served with the 50th, now residing elsewhere are: …William D. Frayne, Ridgewood, N.J.” While this article seems to refer to our Bill Frayne, it seems that this is based on faulty information as he clearly was not a native of Pennsylvania. The official reunion publication ran the photos below of Frayne and French noting that the former was now residing in New London, Conn., as an employee of the Farrel-Birmingham Company, of Buffalo, N.Y.

This probably explains why, in April of 1940, William D. Frayne (age 50) is listed in the census as a guest staying somewhere in Ward 27 in Buffalo, N.Y. His residence is listed as Sea Bright, his occupation is “Supervising Engineer,” the industry “Mfg, etc. (Gear Reduction).

According to BrightHub Engineering, a “reduction gear” is typically a solution to a marine engineering challenge, wherein ship engines are efficient when running at high RPM, but some propellers are designed to be most efficient at lower RPM. A reduction gear allows both the input and output energy to be optimized. Farrel-Birmingham was a manufacturer of a marine reduction gear. Frayne was likely in Buffalo meeting with his colleagues and managers.

In 1941, Farrel-Birmingham would be chosen as a major contractor to produce a new reverse gear system that permitted Navy ships to go from full speed forward to full reverse in about three minutes. Was Bill Frayne working on this?

A newspaper report states that in early September of 1940, Frayne was working in Virginia for Farrel-Birmingham, near Norfolk. Frayne was apparently out at sea aboard a Navy “sub-chaser,” small fast boats equipped with torpedoes, depth charges, and other weapons for fighting enemy submarines. Something went wrong that day, and an explosion resulted in Frayne sustaining third degree burns about his face and arms. After ten days of local treatment, at his request, he was rushed by a special chartered airplane back to Monmouth County to be treated at Monmouth Memorial Hospital in Long Branch. He was said to be in fair condition the following day.

Frayne appeared to make a full recovery, at least as suggested by the 1950 census for Sea Bright, wherein he stated his occupation as a mechanical engineer, working for a machinery manufacturing company.

Bill and Helen Frayne were active in the community. Bill was a member of the Better Sea Bright Association, and the Sea Bright Board of Adjustment, and was appointed to the Conservation Commission in 1971. During World War II, Helen Frayne was active in efforts to support the U.S.O. and the Red Cross.

Helen E. Frayne died August 5, 1967. Bill Frayne died of undisclosed causes on August 17, 1974, age 75. Frayne’s obituary listed two surviving relatives, a sister-in-law and a niece, both living in Tustin, California. This may explain why Bill and Helen Frayne are buried together at Fairhaven Memorial Park in Santa Ana, Orange County, California.

Sources:

Aero Squad to Hold Reunion. (1936). The Evening News, Harrisburg, Penn., September 4, 1936, P. 18.

Clark, Don. (1972). Wild Blue Yonder: An Air Epic. Superior Publishing Company, Seattle, Wash.

Cornell Alumni News. (1937). Ithaca, N.Y., Volume 39, No. 35, 1937, P. 28.

County Wills Offered for Probate. (1967). The Daily Record, Long Branch, N.J., September 8, 1967, P. 5.

Johnston, Charles A. (1967). Photos in Office Tell a Long Tale. The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., March 20, 1968, P. 13.

Frayne-Hoff. (1920). Buffalo Evening News, Buffalo, N.Y., August 9, 1920, P. 17.

Morse, Daniel Parmelee. (1920). The History of the 50th Aero Squadron. The Blanchard Press, New York, N.Y.

Mrs. William D. Frayne. (1967). Obituary, Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., August 7, 1967, P. 2.

Real Estate Transfers. (1926). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., July 17, 1926, P. 15.

Red Bank U.S.O. Drive Advances. (1942). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., July 3, 1942, P. 10.

Ruffin, Steve. (2010). “Dutch Girl” Over the Argonne: The 50th Aero Squadron in WWI. Over The Front. The League of World War I Aviation Historians, Plymouth, Minn., Vol. 25, Number 2, Summer 2010.

Sea Bright Association to meet Tomorrow. (1954). The Daily Record, Long Branch, N.J., December 2, 1954, P. 1.

Sea Bright Awards Three Sewer Contracts. (1971). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., February 17, 1971, P. 8.

Sea Bright Man is Flown to Shore Hospital After Receiving Burns in Blast. (1940). The Daily Record, Long Branch, N.J., September 10, 1940, P. 1.

Secrecy Surrounds Injury of Sea Bright Man Aboard Sub-Chaser; Flown to Red Bank Airport, Rushed to Hospital. (1940). The Daily Standard, Red Bank, N.J., September 10, 1940, P. 1.

Sloan, James J. (1994). Wings of Honor: American Airmen in World War I. Schiffer Military/Aviation History, Atglen, Penn.

Stender, Walter W., & Walker, Evans. (1974). The National Personnel Records Center Fire: A Study in Disaster. The American Archivist, Volume 37, Numb3r 4, October, 1974.

What are Reduction Gears? What is Gear Reduction? (2022). BrightHub Engineering, Albany, N.Y,. Available: https://www.brighthubengineering.com/machine-design/47267-what-is-a-reduction-gear/

William D. Frayne. (2023). Silver Star. The Hall of Valor. Available: https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/47045

William D. Frayne, World War I Pilot. (1974). Obituary, The Daily Record, Long Branch, N.J., August 19, 1974, p. 4.

William D. Frayne and Helen E. Frayne. (2023). Findagravecom. Available: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/206288112/william-d-frayne

Leave a Reply