By John R. Barrows

Editor’s note: Almost 100 percent of the details of military service in this story of Theodore D. Parsons come to us courtesy of Mike O’Neal, a member of the board of trustees for the Golden Age Air Museum, in Bethel, Pa. Mr. O’Neal has made it his life’s work to research, archive, and keep alive the stories of the courageous men who volunteered to fly in rickety airplanes made of wooden frames covered in fabric, without parachutes, in service to America and its allies in the War to End All Wars. He is a regular contributor to Over the Front, the journal of the League of World War I Aviation Historians. Monmouth Timeline is grateful in the extreme for the time and effort Mr. O’Neal has made so that we could bring forth a fresh telling of the story of Ted Parsons of Little Silver, may he never be forgotten.

Many heroes lived… but all are unknown and unwept, extinguished in everlasting night because they have no spirited chronicler.

Horace (65 BCE – 8 BCE)

On September 15, 1917, Theodore D. Parsons arrived at Long Branch, Ontario, Canada, near Toronto, to begin flight training as a member of the U.S. Army’s brand-new first-ever aviation corps. He was born in Shrewsbury, graduated from Red Bank High School, and served as a test pilot in France during World War I, where he crashed five times, but without significant injury. After the war, Ted Parsons earned his law degree from Columbia, opened a practice in Red Bank, and moved to Little Silver. He bought, renovated, and lived in a spectacular mansion on Fox Hill Road called “Sky High.” In 1948, he was appointed Attorney General for the state of New Jersey by Governor Alfred E. Driscoll, where he won acclaim for organizing the new Law and Public Safety Department under the state’s new constitution.

A Brilliant Young Student

On May 24, 1894, Theodore Dwight Parsons was born in LaCrosse, Wisconsin, the first son of Minnie and the Reverend Dwight Parsons. His father was born in Alabama and by the time of Theodore’s birth was employed as a minister in LaCrosse. In 1901, when Ted Parsons was seven, the family re-settled in Shrewsbury, N.J. His father was pastor of the Presbyterian Church in Shrewsbury, on Sycamore Avenue, near the famous Shrewsbury crossroads. He had a younger brother, Reginald, and a younger sister, Miriam.

In 1910, Parsons graduated Red Bank High School at age 15. Thinking him too young for college, Rev. Parsons enrolled Ted in a post-graduate course at Long Branch High School where he finished a four-year program in Greek in 19 months. He attended Princeton University, where he studied aviation and played quarterback for the football team. His brother Reginald also attended Princeton and likewise studied aviation.

Princeton: An Early Center of Aviation Training and Research

According to Mr. O’Neal, Princeton University had two aviation organizations between 1917 and 1919. “The so-called ‘Aviation Corps at Princeton University’ was a civilian-sponsored group whose members actually learned to fly, but was very limited in scope,” he said. “There were only 47 known members, and neither Parsons was among them.”

The other was the United States School of Military Aeronautics (USSMA), one of a series of government-run ground schools (meaning, no actual flying), that graduated a couple of thousand trainees. According to Mr. O’Neal, neither Ted nor Reginald Parsons appears on the “complete” list of those graduates. The Aviation Corps was a “flying only” organization, with virtually no academic content, while the USSMAs were entirely academic, no flying, so the curricula at the schools were very different.

Reginald Parsons enlisted May 18, 1917, attending ground school at Cornell (another USSMA like Princeton), and was then assigned to Selfridge Field, Mich. He was discharged from the Air Service in October of 1917 and re-enlisted in November and was stationed at Rantoul, Ill., and Ellington field, Texas. For unknown reasons he entered the U.S. Navy Reserves on May 4, 1918, as a coxswain (i.e., an enlisted sailor who has physical control of an open boat small enough to be carried aboard another vessel). Reginald was commissioned with the rank of ensign December 31, 1918, and was discharged March 17, 1919.

On May 4, 1917, Ted Parsons enlisted in the Army Officers’ Reserve corps. In June, 1917, he registered for the national draft. According to Mr. O’Neal, his draft registration card indicated he was working as a law clerk in Red Bank at the time.

On July 25, 1917, a local newspaper reported that Ted Parsons was “home from the military camp at Princeton. He intends to become an aviator and is spending today at the aviation grounds near Philadelphia.” And soon he was headed to Canada for more training.

According to Mr. O’Neal:

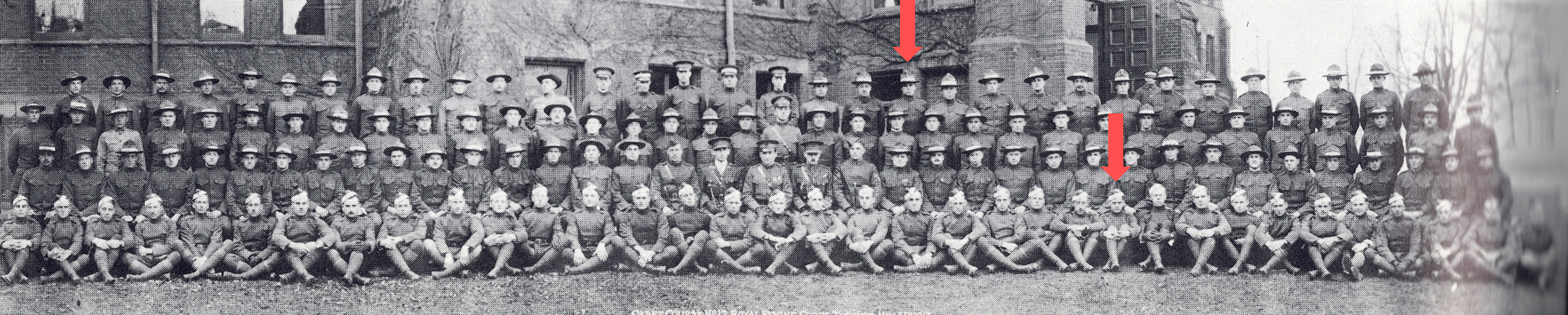

It is a certainty that Parsons was among the group commonly referred to as ‘The First 300,’ a group of 300 aviation cadets who were trained by the British Royal Flying Corps in Canada. Because the U.S. Air Service was ill-prepared to supply flying officers at the U.S. entry into the war and there were few training fields in the U.S. to even produce such officers, the U.S. and Great Britain struck a deal to exchange the flight training of 300 U.S. pilots for use of flying fields in Texas. A Connecticut man named William D. Frayne was with Parson’s graduating class in Toronto, a man who would go on to win the Silver Star and live in Sea Bright most of his life.

Serving as a Test Pilot in the War to End All Wars

When war broke out in Europe in 1914, it had been just eleven years since the Wright Brothers first proved the viability of heavier-than-air manned flight. In that time, development of new aircraft happened largely in Europe, with the United States taking a back seat. The possible applications for aircraft in wartime became readily obvious to the combatants in 1914 on both sides.

The earliest airplanes used in war served primarily reconnaissance roles, gradually finding new ways to contribute to the war effort, such as attacking enemy observation balloons. The earliest bombers involved pilots dropping bombs by hand from the open cockpit. The earliest air-to-air combat involved pilots with shotguns or other hand-held arms. The very first “kill” scored by the legendary German ace Manfred von Richtofen, the “Red Baron,” involved the use of a shotgun from a rear observation seat. Over time, engines were made more powerful, airplane designs improved speed, climbing, and overall aerial performance, and machine guns were fixed to the aircraft, firing forward, improving armament.

But this was still extremely hazardous duty. These early aircraft were made of wood, wrapped in fabric, often glued together with a type of highly flammable adhesive called “dope.” Only thin fabric stood between the pilot and incoming bullets. Cockpits were not only not pressurized, they had no heat, and pilots faced brutal cold temperatures at higher elevations, along with reduced oxygen. Early engines were prone to failure, fuel tanks leaked, and the parachute had not yet been perfected, and was not used until the very end of the war.

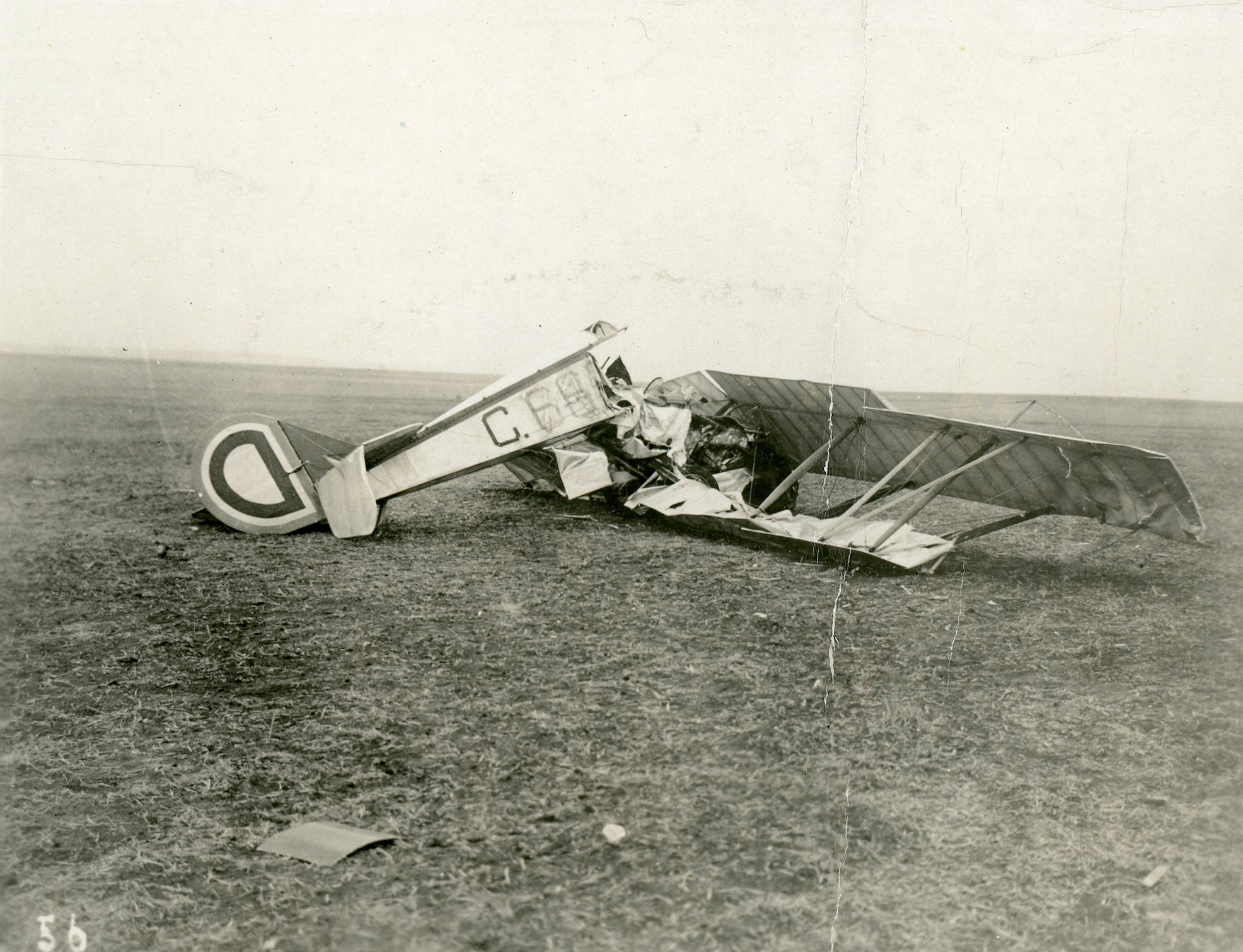

Aircraft of this era were also notoriously difficult to fly, and pilot error was commonplace, with rough landings and “ground loops” commonplace. A “ground loop” occurs when an aircraft becomes unstable while in motion on the ground, resulting in a wing tip touching the ground, spinning the plane around in a loop.

It has been claimed that the role of a pilot in Great Britain’s Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the most dangerous job in the war, with 8,000 men dying just during their 15 hours of pilot training, never even getting a chance to engage the enemy. The average life expectancy of an RFC pilot was estimated to be just 18 airborne hours.

This was no secret. Those who volunteered for the various aviation squadrons knew they were taking one of the greatest risks of the war. Yet many were clearly undeterred by these dangers, especially after witnessing the horrors of trench warfare of the era. Better to die in a dashing and adventurous new flying machine, the most modern technology of the day, than go over the top into a cloud of mustard gas and a hail of machine gun fire across No Man’s Land.

Test Pilot Ted Parsons

Ted Parsons mustered in at the Essington Barracks, just outside of Philadelphia. Princeton records indicate the date of enlistment as August 23, 1917, at Bedloe’s Island (today known as Liberty Island, home to the Statue of Liberty), and note that he remained at Bedloe’s Island until September 15, 1917. That day, Parsons arrived at Long Branch, Ontario, Canada (yes, there is another town called Long Branch besides ours in Monmouth County), outside Toronto, to begin his flight training, and according to Mr. O’Neal, “Princeton records show that he remained just under a month, transferring to the University of Toronto on October 10 to begin his ground school training.” By September 26, 1917, local newspapers here reported that Parsons was “in the aviation corps stationed at Toronto.”

Around November 15th, according to Mr. O’Neal, Parsons was transferred from Toronto to Hicks Field, outside Fort Worth, Texas, a training field for the Air Service, along with the majority of the other cadets and instructors. Parsons continued his flight training at Hicks, eventually earning his Reserve Military Aviator Rating and receiving his commission to second lieutenant on February 5, 1918. On February 20, 1918, a local newspaper reported that “Theodore Parsons, son of Rev. Dwight L. Parsons of Shrewsbury, is home on a furlough from Camp Taliaferro, Texas, where he has been in service with the 139th Aero Squadron. He was recently commissioned as a second lieutenant He has made several flights and likes the work immensely.”

According to Mr. O’Neal, on February 26, 1918, Parsons, assigned to the 139th Aero Squadron when it was formed at Taliaferro, sailed for England with the squadron later in February, aboard the SS Olympic. The squadron was at Winchester, England, on March 1, but headed to France to continue flight training. Parsons was initially assigned to the 2nd Aviation Instruction Center (AIC) at Tours in central France arriving on March 2. He remained ten days before heading for the 3rd AIC at Issoudun in central France to continue his training on fighter airplanes.

Most sources show that Parsons remained with the 139th until the end of the war. He was assigned to the 139th in the U.S. and sailed to France with the squadron. Here the records diverge. Research done by John J. Smith, a WW I veteran and one of the foremost WWI aviation researchers in the U.S., indicate Parsons was at Issoudun until early May, then at Toul in northeast France, and finally at nearby Belrain with the 139th by September 25.

Ted Parsons’ service summary as submitted to Princeton University indicates that he was at Issoudun from March to July 1918, and that from July to February of 1919, three months after the end of the war, he was assigned as a test pilot at an unknown location. Since his name does not appear in the rather well-documented combat record of the 139th Aero Squadron, it is likely that he did in fact remain a test pilot and did not see service with the 139th at the front.

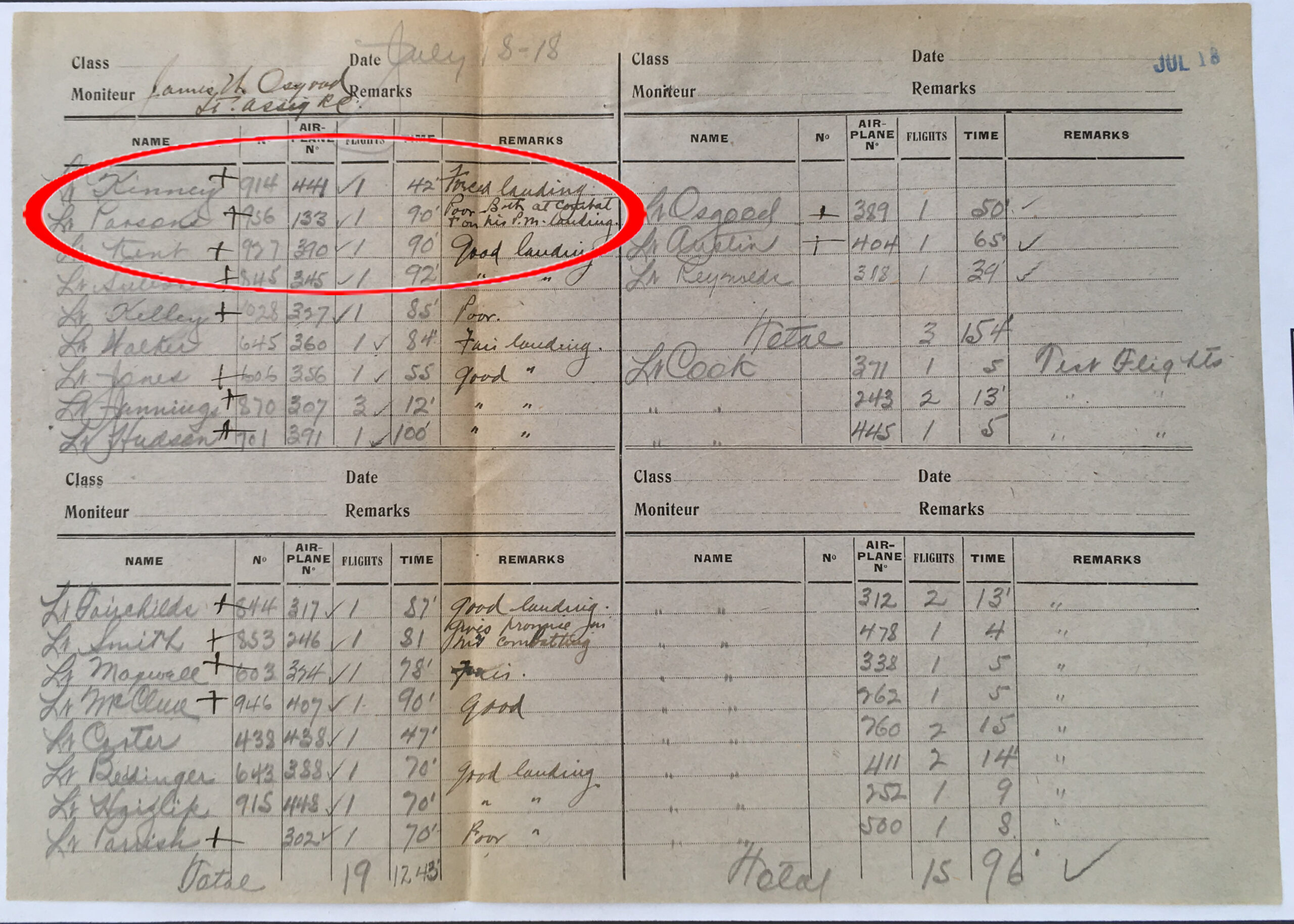

Daily field records from Issoudun reveal two different phases of Parson’s flight training. The first, from July 13, 1918, involved transitioning from trainers to the Nieuport fighters. He would have gone through a taxiing class, a couple of hours of dual-control flight with a second pilot aboard, about five hours of solo flight time, and practice at landings, formation flying, and cross-country flying. The second phase entailed learning aerobatics and fundamentals of air combat. If they survived all that, pilots like Parsons were then sent to Le Ecole de Tir Aerienne, the Aerial Gunnery School at Cauzeaux for couple of weeks, then back to Issoudun to await assignment to a combat unit. For Parsons, the war would come to an end before he could be assigned to a forward fighting unit.

According the records, Ted Parsons was inconsistent in his flight training performance, and received middling grades for landings, air work, etc., and so it is possible that his test pilot assignment was a result of his having been judged to need more time in the air before being transferred to the front, and going up against the formidable German fighters of the era, who had superior aircraft and aviation armament.

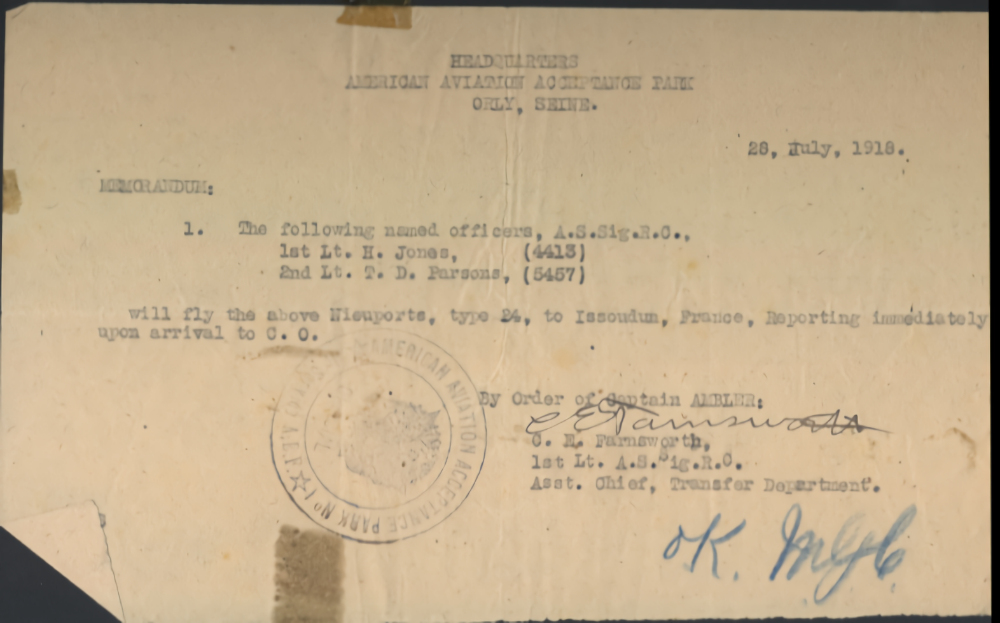

The copy of his orders to fly a Nieuport biplane from Orly to Issoudun is telling. Orly was a repair depot, so Parsons spent some time there as a “ferry pilot.” This was common for pilots who were awaiting new assignments. There were some full-time ferry pilots, but it was more common to simply shanghai a competent available pilot to move airplanes from one place to another. What is clear from the records is that Parsons was not assigned to Issoudun as a test pilot, he passed though as a student, but did not stay on staff as his name does not appear on any of the active duty rosters. “The 3rd AIC at Issoudun was easily the most active flight instruction center for American pilots in France,” according to Mr. O’Neal. Movement of aircraft from place to place was an everyday activity for pilots.

According to Mr. O’Neal, the records make it clear that Parsons was serving as a test pilot at some of his other stops in France, but in those early years of U.S military aviation there were a number of different types of test pilots performing very different roles. We typically think of test pilots as being responsible for trying out newly developed experimental aircraft prototypes, but that was clearly not Parsons’ job. He was either test-flying aircraft that were newly delivered and assembled for the first time, or he was test-flying aircraft that had been returned for repair and needed to be proven airworthy before being returned to the front. All those rough landings and ground loops happening to trainees meant a steady stream of aircraft coming into and then out of the repair hangar, and these planes had to be flown and tested before they could be returned to active duty.

Test pilots who worked on these newly assembled or repaired aircraft worked long days, flying 12-20 planes in a day for just ten to twelve minutes each. It was hardly the romantic adventure we associate with test pilots as portrayed by Hollywood over the years, such as Test Pilot (1938), a movie starring Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, and Myrna Loy, or the portrayal of legendary test pilot Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff (1983).

Accounts of Parsons life in later years noted that his time as a test pilot included his having survived five crashes without serious injury. As Mike O’Neal points out, there are degrees of crashes, and given the general unreliability of aircraft of the time, this is highly likely to be true.

With the war over, Ted Parsons finally sailed home on February 2, 1919, aboard the SS Stockholm, arriving on February 12 in New York City. He received his final discharge from the national service on March 31, 1919.

Postwar Domestic Bliss

In 1919, Theodore Parsons was admitted to the New Jersey Bar and then opened a law practice in Red Bank, and moved into a home on Branch Avenue in Little Silver. Still passionate about football, Parsons championed bringing the sport to his alma mater, Red Bank High School, and became the school’s first football coach.

In August of 1935, Parsons purchased “Sky High,” the former Brooks residence on Fox Hill Road, off Branch Avenue in Little Silver. The house has been described as “of a very unusual type of architecture with high wooden columns and flights of flagstone steps near the front entrance.”

Originally a mansion built by the late John T. Lovett, owner of Lovett’s Nurseries, one of the most prominent such businesses in the country, the property comprised eight acres, on a plateau 181 feet above sea level, described as the “highest point along the coast south of the North Shrewsbury River to Cape May.” After Lovett’s death, the property changed hands several times and was abandoned, during which time it was all but completely ruined by vandals. Parsons purchased the house, and invested in wholesale renovations that took more than a year to complete, and he and his family, including the Reverend Parsons, lived there the rest of their days.

Ted and his wife, Margaret Morford Parsons, had two sons, Theodore Jr., and John, and a daughter Margaret. The family was very active in the community, and hosted a number of prominent events at the family home.

A Call to Serve his Native State

On February 4, 1948, Parsons was appointed New Jersey Attorney General by Governor Alfred E. Driscoll, and served until 1954. Parsons joined Driscoll’s administration during one the most challenging periods in modern New Jersey history, the effort to overhaul the state’s badly outmoded constitution. The state court system of that era was a byzantine array of overlapping and bewildering areas of jurisdiction. Lawyers of the era often had to specialize in the inner workings of just one of the many different court systems in order to achieve success. A person being sued in, say, family court could counter-sue in chancery court, resulting in years of stalemate. For outsiders, it was a closed system that offered very little relief. The weaknesses in the state’s constitution helped contribute to a long era of rampant corruption in public officials, none more famous that Jersey City’s legendary “Boss” Frank Hague.

In 1947, New Jersey ratified a new constitution that overhauled the state’s judicial and executive functions. Parsons was not involved in creating the new constitution, but he was the first attorney general to serve under the new document. He immediately set about organizing a new state department to focus on criminal justice. The following year, Governor Driscoll signed the Law and Public Safety Act of 1948, N.J.S.A. 52:17B-1, et seq., which created the Department of Law & Public Safety, a new cabinet-level agency, headed by Attorney General Parsons. The law placed several agencies under his supervision, including the New Jersey State Police and the Department of Law (renamed the “Division of Law”). The 1948 Act also gave the Attorney General authority over divisions regulating alcoholic beverages, motor vehicles, professional boards, and weights & measures. “It was a hard, difficult task that required tact and diplomacy,” said Driscoll of Parson’s efforts.

Parsons also presided over the legalities the state faced in the construction of the New Jersey Turnpike in 1952, a major priority for Governor Driscoll, who wanted the vast numbers of out-of-state drivers passing through New Jersey taken off local roads. One major challenge was Turnpike construction in the city of Elizabeth, where either 450 homes or 32 businesses would have to be destroyed, depending on the chosen route. Either way, there would be lawsuits, but the Turnpike was completed in an astonishingly short time.

Parsons experienced some minor controversies during his period as attorney general, of the sort that comes with that territory, but he was generally considered to have been honest and effective in his role. After leaving office, he returned to his Red Bank law practice, and his home and family in Little Silver, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Legacy

Ted Parsons was a trustee for the New Jersey State Bar Association and a member of the American Bar Association, and he was involved in many community activities and groups over the years, e.g., president of the Lion’s Club. Ted’s brother Reginald became an apple rancher at Leavenworth, Washington; his sister Margaret Marion Parsons, later Mrs. Richard H. Foster, lived in Bath, England.

After leaving the military, Parsons never flew again, citing the danger and risk to his family. The Department of Law and Public Safety that he formed is still New Jersey’s law enforcement governmental division.

Sky High, the former J.T. Lovett mansion that Parsons saved from ruin, is still a prominent residence in Little Silver today.

Sources:

Aviator on Furlough. (1918). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., February 20, 1918, P. 13.

Clark, Don. (1972). Wild Blue Yonder: An Air Epic. Superior Publishing Company, Seattle, Wa.

The Danger of Flight. (2016). Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund, London, England, June 30, 2016. Available: https://www.rafbf.org/news-and-stories/raf-history/danger-flight

Former Attorney General Theodore Parsons Dies. (1978). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., October 21, 1978, P. 1.

History of the AG’s Office. (2022). State of New Jersey, Department of Law & Public Safety, Trenton, N.J. Available: https://www.njoag.gov/about/history/.

Items of Local Interest. (1917). The Freehold Transcript, Freehold, N.J., November 23, 1917, P. 3.

Johnson, Nelson. (2014). Battleground New Jersey. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, N.J., 2014.

Johnston, Charles A. (1949). Parsons Ready to Devote Active Career to Three-Fold Task in His New Post. Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., January 23, 1949, P. 1.

Joiner, Stephen. (2013). The First Test Pilots. Smithsonian Magazine, Washington, D.C., November, 2013. Available: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/the-first-test-pilots-7897494/.

Many Red Bankers Join Officers Corps. (1917). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., May 3, 1917., P. 6.

O’Neal, Michael. (2021). A Bad Day at Issoudun – 16 August 1918. Over The Front, League of WWI Aviation Historians, Warren, N.J., Spring 2021, Volume 36, Number 1, P. 16-38.

O’Neal, Michael. (2021). A Brief History of the United States School of Military Aeronautics at Princeton University. Over The Front, League of WWI Aviation Historians, Warren, N.J., Spring 2021, Volume 36, Number 3, P. 52-66.

O’Neal, Michael. (2019). The Original Flying Tigers – The Flying Corps at Princeton University. Over The Front, League of WWI Aviation Historians, Warren, N.J., Autumn 2019, Volume 34, Number 3, P. 251- 275.

Shrewsbury Church has 12 in Service. (1917). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., September 25, 1917, P. 2.

Shrewsbury News. (1917). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., July 25, 1917, P. 16.

Theodore Parsons Buys Lofty Home. (1935). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., August 8, 1935, P. 1.

much of the information about Theodore D. Pardsons, my father, is inaccurate.

You said that before. I asked what we should change, you never replied. Don’t just throw accusations around, be specific please!

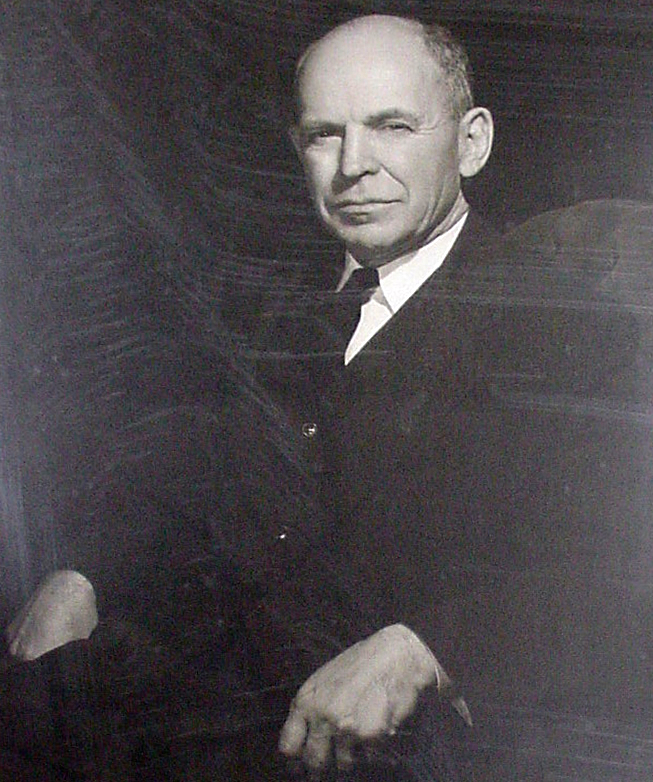

the pic in uniform is NOT

TedParsons, my father. Inaccurate infor.

It has been removed. Were you to provide an accurate photo, we would be DELIGHTED TO USE IT!!!