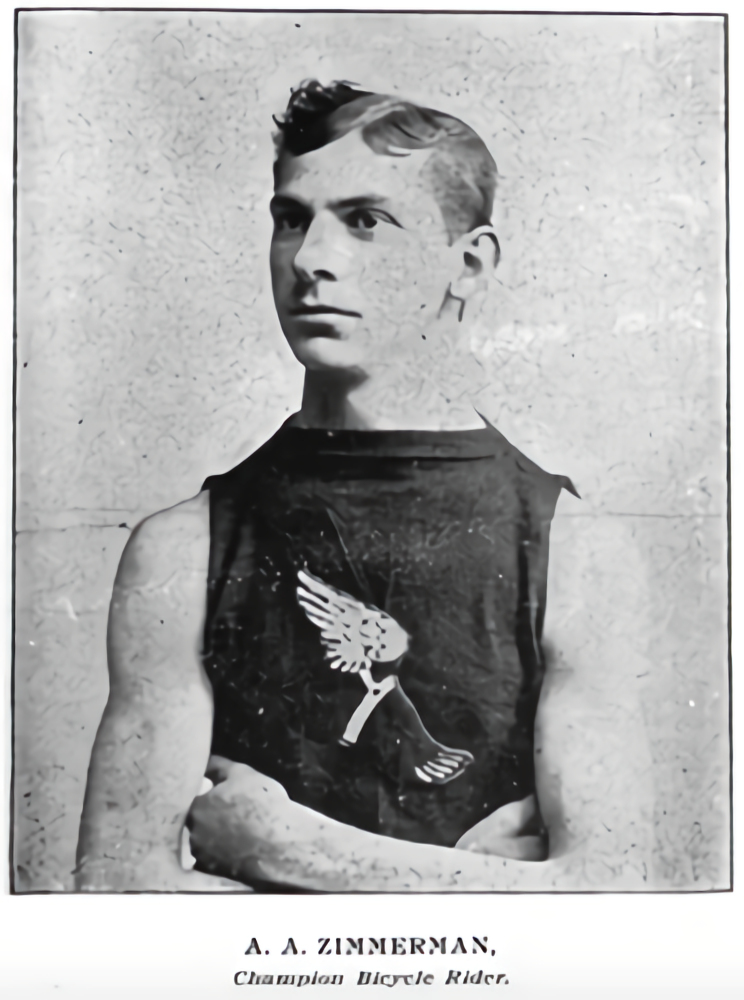

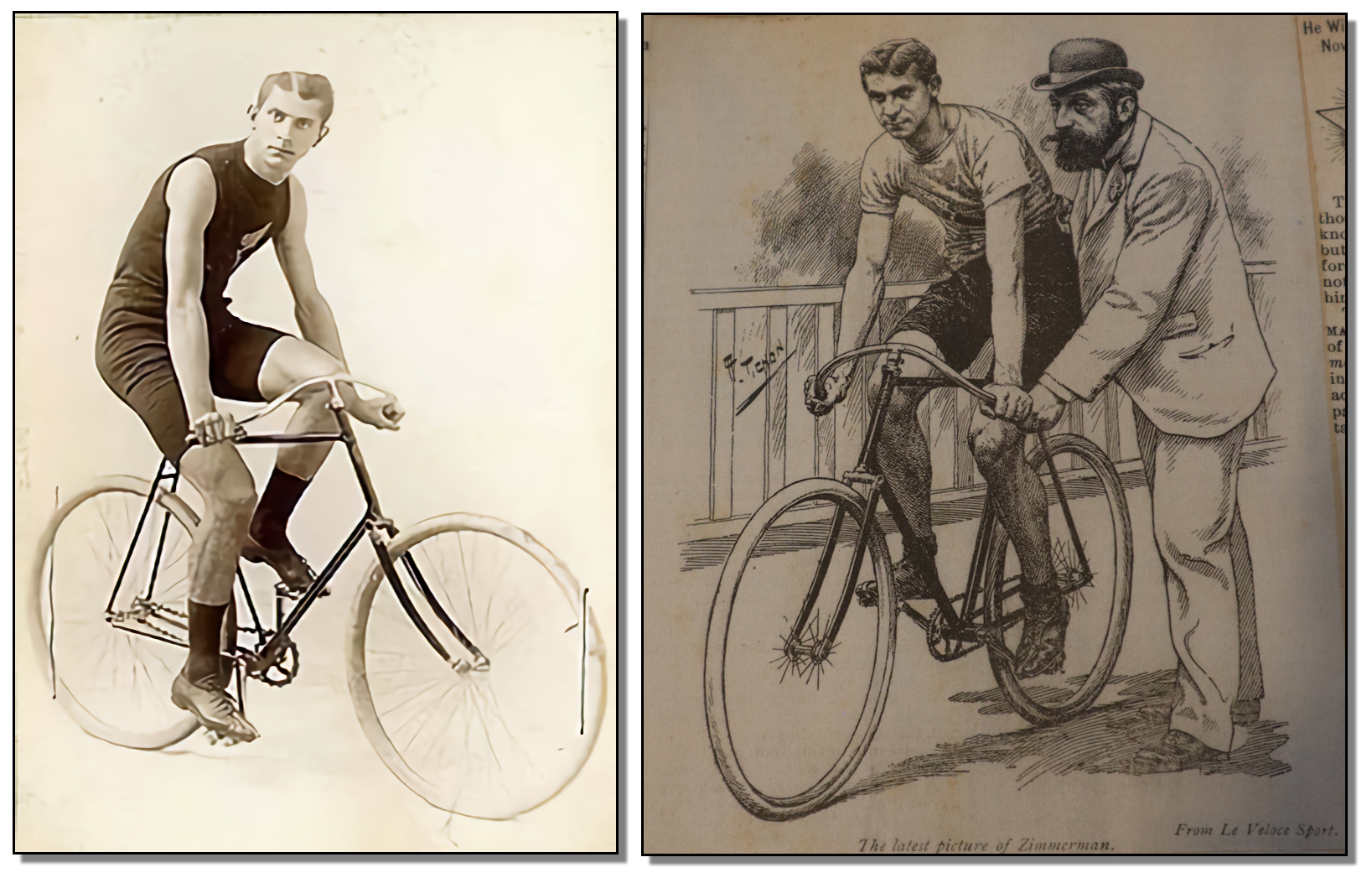

Editor’s note: On June 30, 1892, in London, Arthur A. Zimmerman of Freehold broke the world’s record for the fastest time covering a half-mile on a bicycle from a standing start, with a time of one minute and five seconds. That same month, Zimmerman won the one-mile and five-mile cycling championships held at Leeds. For Zimmerman, it was just another example of his domination of international bicycle racing.

By Mark A. Wallinger

Arthur Augustus Zimmerman might be considered the “Athlete of the Century” in New Jersey – the 19th century, that is.

Born in Camden on June 11, 1869 – just four years after the Civil War ended – he was the third child born to Anna and Theodore Zimmerman, a real estate broker, but Arthur mostly grew up in Freehold. He was a good athlete in the high jump, long jump, and triple jump at his military school, and considered a career in real estate law, but instead opted to become one of the greatest cyclists in world history.

He was a three-time U.S. champion, in 1890, 1891, and 1892. In 1893, he was the first-ever world cycling champion. During this time, and for most of his adult life, he lived at 1106 Fifth Avenue in Asbury Park, with his wife, C. Blanche Zimmerman, and their daughters Ella and Hortense.

But Zimmerman was more than just a champion in an era when cycling became a booming obsession. He was an athletic innovator, who literally wrote the book on cycling tactics and training. His ideas on nutrition were years ahead of their time and influenced performance-based training.

He was also popular, which could not be said of all his peers.

Zimmerman was a fun-loving, agreeable character from New Jersey who could get three hours of sleep the night before a race and then go out and break a time record. The working-class Zimmerman broke down class barriers by changing amateur racing from a sport for the wealthy to a sport with universal appeal. He appeared in advertisements for bicycle companies, and people were fascinated with his effortless victories. Zimmy was known for his short bursts of incredible speed, holding back until the last lap when he would surge forward to defeat his competitors.

Graham Jones, Capo Velo Cycling Collective

Zimmerman’s success and career trajectory resulted in the very definition of what it meant to be an amateur versus a professional athlete. And his impact reached past simply sports, but into the arena of promotion and marketing as well as civil rights.

He was one of the first world-famous athletes. After all, basketball had just been invented (1891); athletes like Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey had not been born (1895); and the modern Olympics were still…just a committee (1894). Boxing, golf, and horse racing were big sports at the time, but cycling emerged and captured the nation’s forward-thinking imagination.

Example: In 1892, Gentleman Jim Corbett knocked out John L. Sullivan in New Orleans to win the world heavyweight boxing championship before 10,000 fans in a one-time event. Zimmerman routinely raced before more than 10,000 fans.

“Zimmy,” as he was known, stood nearly six feet tall and had long legs that gave him exceptional acceleration and the ability to pedal fast. He won nearly 1,400 races, according to The New York Times. Although his losses were not recorded, he dominated when he rode. During the 10-year peak of his career (1889-1899), he averaged a major win per week throughout the U.S., England, Ireland, Europe, and Australia.

It’s hard to compare different eras, but modern racers Greg LeMond had 79 professional tour wins and Lance Armstrong 72. Those numbers do not reflect wins in heats, but only final tour-sanctioned events. Zimmerman’s race results probably do include heats and all of his competition occurred in an era before athletic governing bodies and sanctioned events.

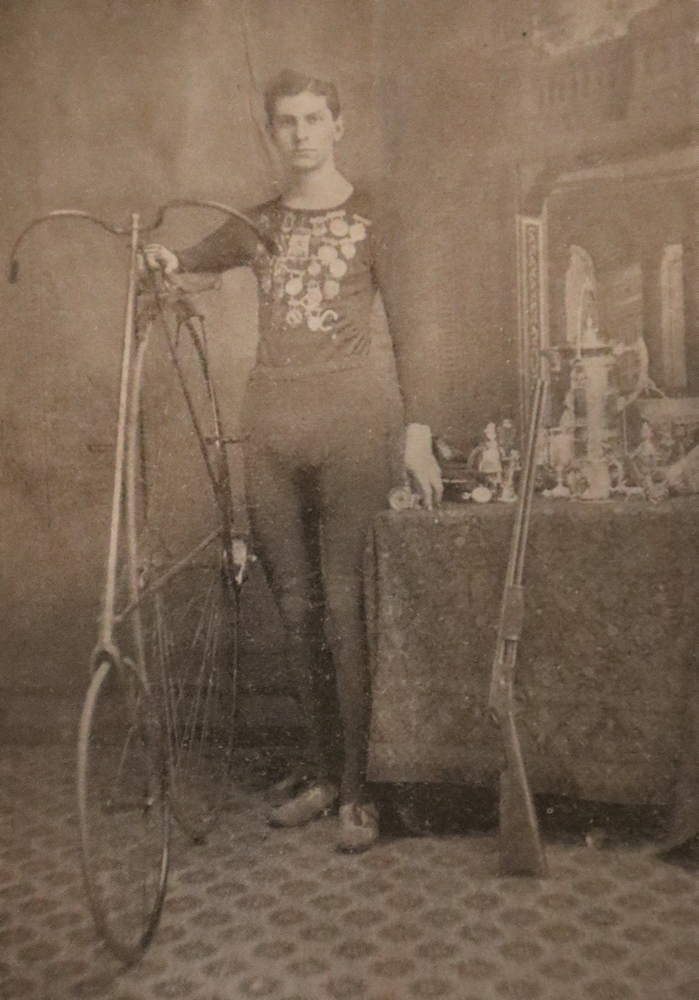

Back in the early stages, cyclists rode the “penny-farthing,” that odd-looking old bicycle with the massive 55-inch front wheel and the much smaller back wheel. They rode on solid tires riding on mostly horse trails and mostly east of the Mississippi. Rain could make trails muddy, or unrideable. Falls were common, often leaving riders seriously hurt, or at least unconscious.

Zimmerman also raced on another type of penny-farthing that had the small wheel in the front for steering, with the large wheel still used for pedaling. These penny-farthing bicycles were eventually replaced by the more traditional two-wheeler we think of today, with both wheels approximately the same size, which made cycling accessible to the masses.

In 1890, Zimmerman witnessed a race in Illinois where English rider Herbert E. Laurie used a new kind of tire – pneumatic – an air-filled tube pioneered by John Boyd Dunlop (think: car tires) just two years earlier. First greeted by “hoots and jeers,” it was at first considered an unfair advantage. But the innovation continued to evolve.

Because following riders over many miles was difficult, and foul weather often ruined the experience, local fairgrounds were used, or stadiums were built – often called velodromes, exclusively for cycling – and these were the first places the sporting masses could gather to watch racing, which morphed from long distances to sprints around a banked track.

The racing in those days extended over a greater part of the country. Nearly every state and county fair had bicycle racing as an attraction. [We] rode principally on dirt tracks – trotting tracks – and we made a regular circuit, going from one town to another and riding practically every day. It was often the case that the riders, after spending several hours on a train, would be obliged to go immediately to the track where they were billed to appear and, without any warming up, go out and ride. This happened day after day.

A. A. Zimmerman, in the Newark Evening News, 1912

According to cycling historian and author Peter Nye, “Zimmerman was reputed to win 47 races in one week, which probably included heats, from the quarter mile to 25 miles, and finished some seasons with 100 or more victories.”

When the most lucrative racing moved to the track, Zimmerman could still dominate in the distance races. In the 1893 championships there was a 50-mile event and English distance star Frank Shorland, who left a dozen rivals drifting behind and gasping for air. Not Zimmerman, who won giving him a sweep of the English cycling titles as well.

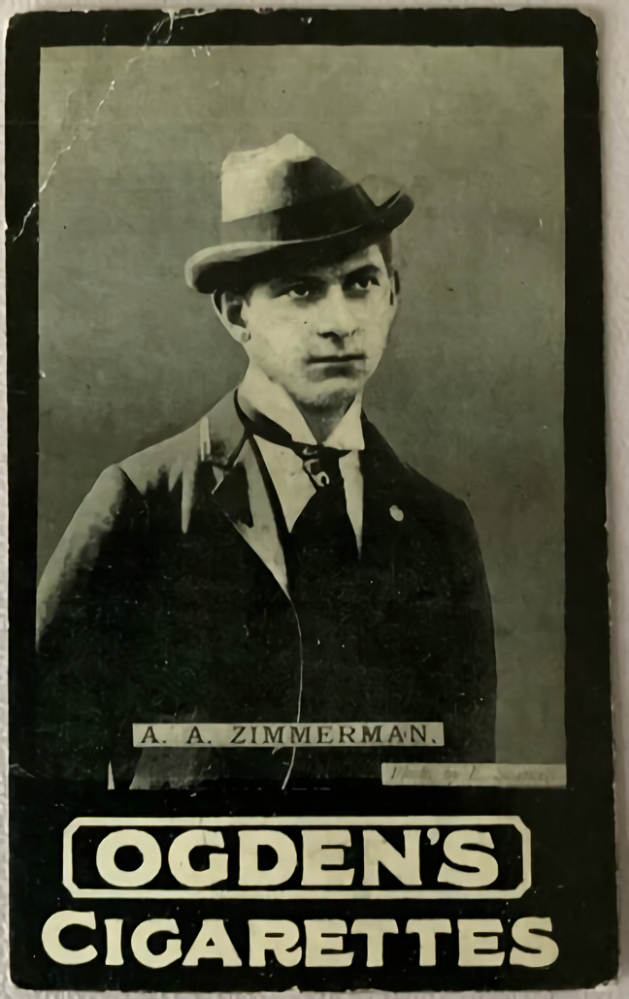

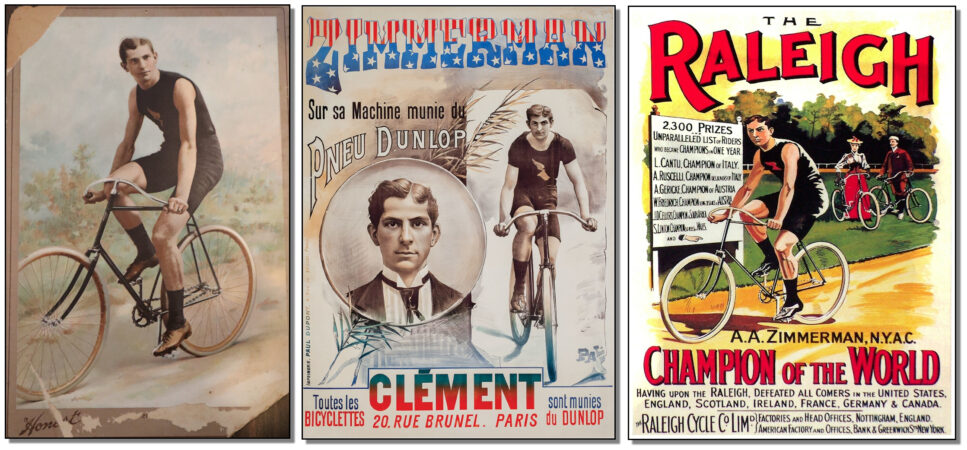

The bicycle boom was on, and he capitalized. There were Zimmerman shoes, and Zimmerman toe clips (used later in his career after copying someone else) and Zimmerman racing clothes. He also did advertisements for cigarettes and was lured by promoters for complete tours of Europe and trips to Australia.

The Zimmerman Problem

In 1893, the first-ever cycling world championship was for track sprints and only open to amateurs. Zimmerman’s father was a member of the New York Athletic Club (NYAC) and so the son also wore the trademark winged foot on the front of his jersey. But the NYAC was dedicated to amateur athletes. In fact, The International Cycling Association – the first international body for cycle racing – was formed because of the “Zimmerman problem,” which was that he had been gifted 29 bicycles, several horses and carriages, a half dozen pianos, a house, land, and furniture, for winning races. He also had an agent, who booked events in Europe and derived additional income for endorsing several products. Although amateurs also received medals, gifts, and payments from promoters, Zimmerman’s compensation and financial benefits made it all but necessary for him to turn professional.

Internationally, he was offered $10,000 in appearance fees, paid in gold, plus 30 percent of the gate. Race purses were secondary, but he could win $1,000 (of the total $5,000 event prize money) for winning, which he often did. Raleigh bicycles offered him $1,000 to ride its bikes. Promoters in Italy and Belgium formed syndicates to lure him there.

It is hard to truly grasp what that era of cycling was like and how it fed the imagination of a population that had yet to experience cars (which would overwhelm the bicycle craze shortly thereafter – bankrupting many bike manufacturers) and airplanes.

Cycling became such a craze that thousands of cyclists rode by the White House on July 19, 1892, calling for President Benjamin Harrison to build better roads. A petition for better roads was signed by 150,000 Americans and it greatly increased the use of macadam for paving in the U.S. Why? Transportation at that time was dominated by horses, mostly walking at a gait of around four miles per hour. Bikes could easily go 15 miles per hour.

Bicycles started out at $65 to $150 and were initially for wealthy urban riders, who enjoyed the freedom of avoiding horse-drawn carriages. In June 1896, the opening of a five-mile, bicycle-only riding path from Prospect Park to Coney Island in New York City had a parade of 10,000 bicycles and 100,000 spectators five rows deep – roughly the entire population of Newark, N.J. at that time.

The NYC Police commissioner took note and pedaled himself four miles daily to his office at 300 Mulberry Street, and later established a “scorcher squad” of 29 bicyclists who frequently chased after criminals or runaway carriages. That was just four years before the Police Commissioner – Teddy Roosevelt – became U.S. president in 1901.

In 1896, there were four million bicycles in the U.S., and across the nation, bicycle factories ran 24 hours a day. Many riders were women, who took advantage of the opportunity to be independent, and this was seen as revolutionary:

Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. It has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.

Suffragist leader Susan B. Anthony, 1896

The cycling craze contributed to a significant increase in demand for rubber worldwide, to such an extent that it affected the economies of rubber-producing countries in the 1890s.

The Wright Brothers opened their famous bicycle shop in Dayton in 1892 at the peak of Zimmerman’s fame. Many manufacturers used his innovations for bicycles and applied them to early cars, which would become its own craze, and airplanes, which would also usurp bicycles. Motorcycles (first called “motocycles”) were invented to be “pace setters” for bike racers.

Zimmerman Takes the Next Step

Zimmerman wrote a book called “Points for Cyclists with Training,” which was one of the first-ever sports training books that combined workout with diet and exercise as well as technique. He outlined how to:

- Breathe and rest;

- Tuck the head for an aerodynamic position;

- Pedal with the proper cadence; and,

- Save energy until the sprint.

Zimmerman did more than just write the book on proper techniques to share with racing enthusiasts. Recognizing that the dynamics of racing were different in Europe compared with the U.S., he re-wrote and released a second training guide that focused on racing in Europe: Zimmerman Abroad and Points on Training in Europe.

He was nicknamed by reporters as “The Jersey Skeeter,” comparing him to fleet-flying mosquitos, while abroad he was just the “Flying Yankee.”

The New York Times described Zimmerman’s performance in Europe in 1892: “he started in 100 races, finished first in 75, second in 10, and third in 5. The same year he broke the 2,000-meter and 3,000-meter records in Germany.” He set world records, or broke his own, several times. In 1883, he won 101 of the 110 races he entered.

At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, he set two records – one for the fastest mile – and then boarded a train for Indianapolis. When he got off the train, he was greeted by a band and hundreds of cheering fans. That was for a race on August 24 with the former U.S. champion L.F. “Birdie” Munger and future champion Marshall W. “Major” Taylor, and the Indianapolis Sentinel called the race “far superior to anything of the kind ever seen in the world.”

The story-behind-the-story from that event was the dinner gathering Munger organized with Zimmerman and the African American teenager Taylor, as well as fellow champion cyclist “Wee Willie” Windle. These four are considered the “Mount Rushmore” of U.S. bicyclists of the Gilded Era (although of course it was 30 years before the actual Mount Rushmore would be started).

Zimmerman was idolized by Taylor, and he reached out on behalf of the young racer often, even helping him with strategy at times in the coming years as Taylor became a sensation himself.

Zimmerman won the race in Indianapolis, with a record of 2:12 – three seconds faster than the year before. He won a diamond-encrusted gold cup. It would be Munger’s last race (he later built two of the largest bicycle companies ever and later went into autos before going bankrupt) and Taylor would emerge as the young and future talent and one of the first African American champions in the U.S., and later the world. By the time Taylor retired, an era had ended, as the bicycle craze had been replaced by automobiles.

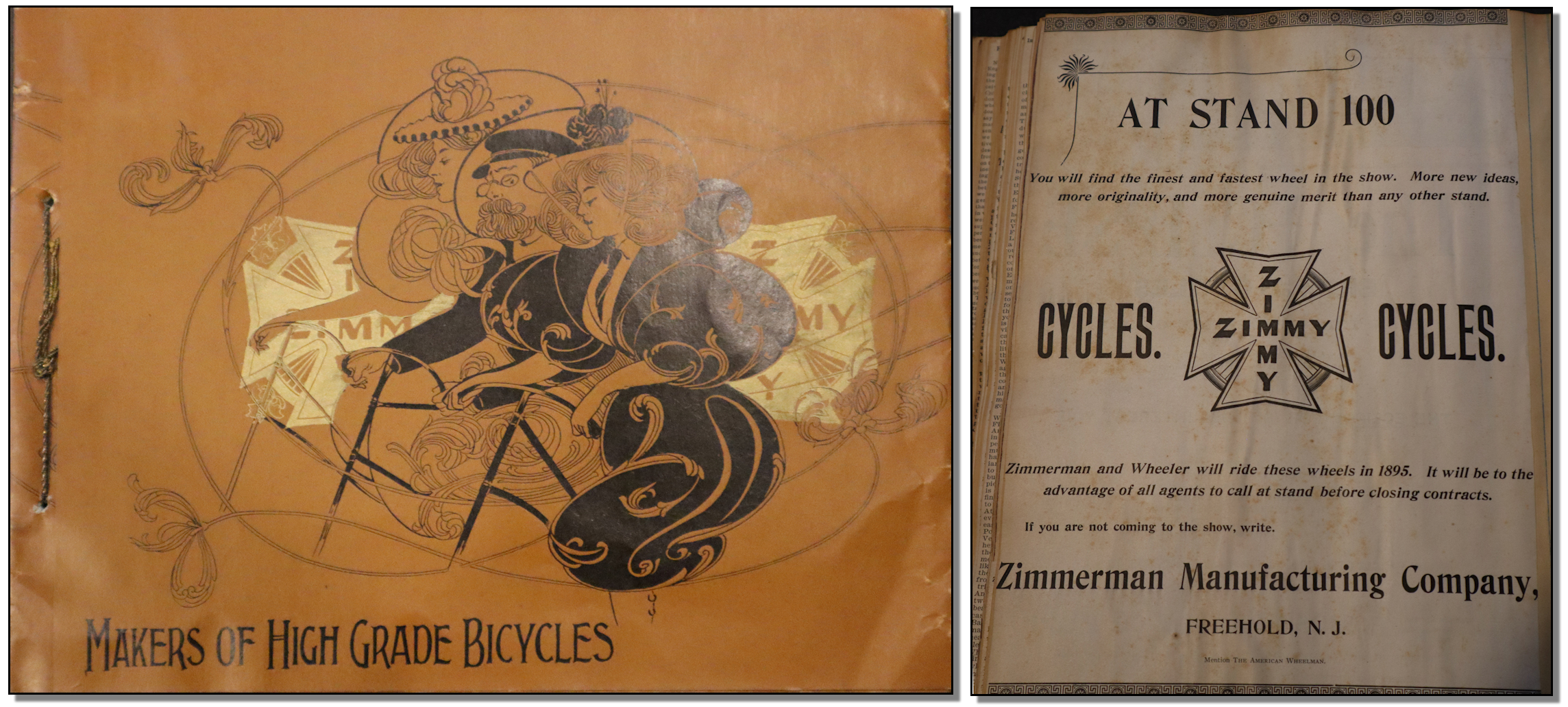

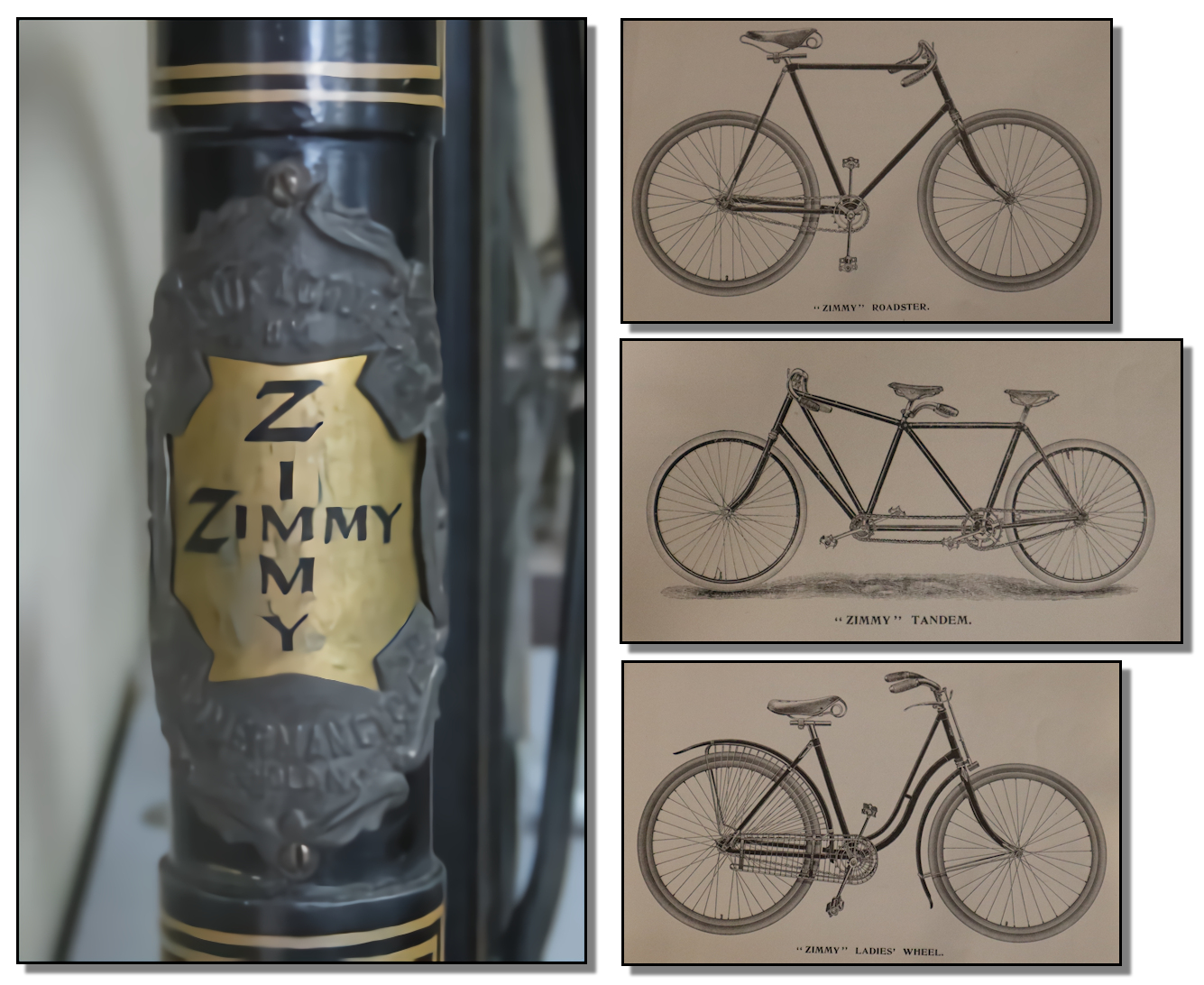

When he retired, Zimmy opened the Arthur A. Zimmerman Cycle Co. on Elm Street in Freehold, which manufactured several models of his “Zimmy” bicycle. The former Metz Bicycle Museum at 54 W. Main St. in Freehold, had a Zimmy on display. When Founder David Metz died in 2014, it was auctioned off for $15,210.

Legacy

So, he was a great athlete, perhaps the first sports superstar along with boxers John L. Sullivan and James J. Corbett (who also chose Asbury Park for his training camp). Zimmerman was a savvy marketer and promoter who was well-compensated for his talents. His arrival alone warranted appearance fees, and crowds and bands would meet his train when he visited for a race.

When the ship carrying Zimmerman home from the world championships in England crested the horizon, cannons boomed, and flags around town waved. He walked off the ship, and a procession formed to escort him to Ocean House – a civic hall – where he was the guest of honor. When he retired from racing, he managed a hotel down the shore and lived in nearby Point Pleasant.

He died of a heart attack while visiting Atlanta in 1936 at the age of 67, long forgotten by a world taken over by cars and airplanes and new sports superstars, who rode the path set by Zimmerman all those years before.

Oddly, it wasn’t until 1989 that he was inducted into the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame, which had moved from Somerville, N.J., to Davis, Calif. He is buried in Atlantic View Cemetery in Manasquan.

About the Author

Mark A. Wallinger is a former award-winning professional journalist and a senior marketing and sales executive with a passion for history. A native of New Jersey, Mr. Wallinger currently resides in Westerville, Ohio.

Sources:

A.A. Zimmerman Dies: Ex-Champion Cyclist. (1936). The New York Times, New York, N.Y., October 22, 1936, P. 25.

Images: Arthur A. Zimmerman Personal Scrapbook. (1936). Monmouth County Historical Association, Freehold, N.J.

Jones, Graham. (2022). Cycling’s Enduring Legacy: The “Golden Age” of Cycling. Capo Velo Cycling Collective, Concord, Calif., June 2022. Available: https://capovelo.com/cyclings-enduring-legacy-golden-age-cycling/.

Mrs. Arthur A. Zimmerman. (1962). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., August 24, 1962, P. 2.

Nye, Peter Joffre. (2010). Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Neb., 2010.

Our Zimmerman Wins. (1892). The Shore Press, Asbury Park, N.J., July 1, 1892, P. 1.

Pridmore, Jay, & Hurd, Jim. (2001). The American Bicycle. Motorbooks Intl., Beverly, Mass., January 1, 2001.

Leave a Reply