Book Review: Reaping the Whirlwind, by Dominic Etzold

©2023 Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, Pa., $34.99, available from Schifferbooks.com, Barnes & Noble, AbeBooks, Amazon, and other retailers.

Book review by John R. Barrows

The Battle of Monmouth is an example of an important event in military history in which both sides claimed victory. It is by no means unique in that regard, but it points to the complications inherent in making such determinations. In 1778, the British completed their march from Philadelphia to New York City with no involuntary delays, and what they considered relatively minor casualties from their encounters with rebels. George Washington’s Continental Army awoke the morning after the battle to find themselves alone and in control of the disputed territory, an ages-old definition of victory.

But focusing on who won diminishes the greater implications of the Battle of Monmouth. It cemented George Washington’s position as commander-in-chief, silencing his critics. It contributed to the British abandoning their northern campaigning in favor of a new southern strategy, which ultimately failed. Further analysis from historians suggests that the colonials, in the end, came out of the Monmouth encounter with the upper hand going forward.

The German submarine attacks against shipping off the coast of North America during World War I is another example where both sides believed they had achieved their objectives. The Americans, both while clinging to neutrality and even after entering the war, viewed most of the damage as happening to smaller sailing cargo vessels, and other mostly non-strategic or non-military targets. The U.S. strategy made a priority of providing military vessels and shipping war materiel to the Entente Powers, and the loss of a few thousand tons of fish, or lumber, or coal, was considered an acceptable cost that showed that this strategy was the right one.

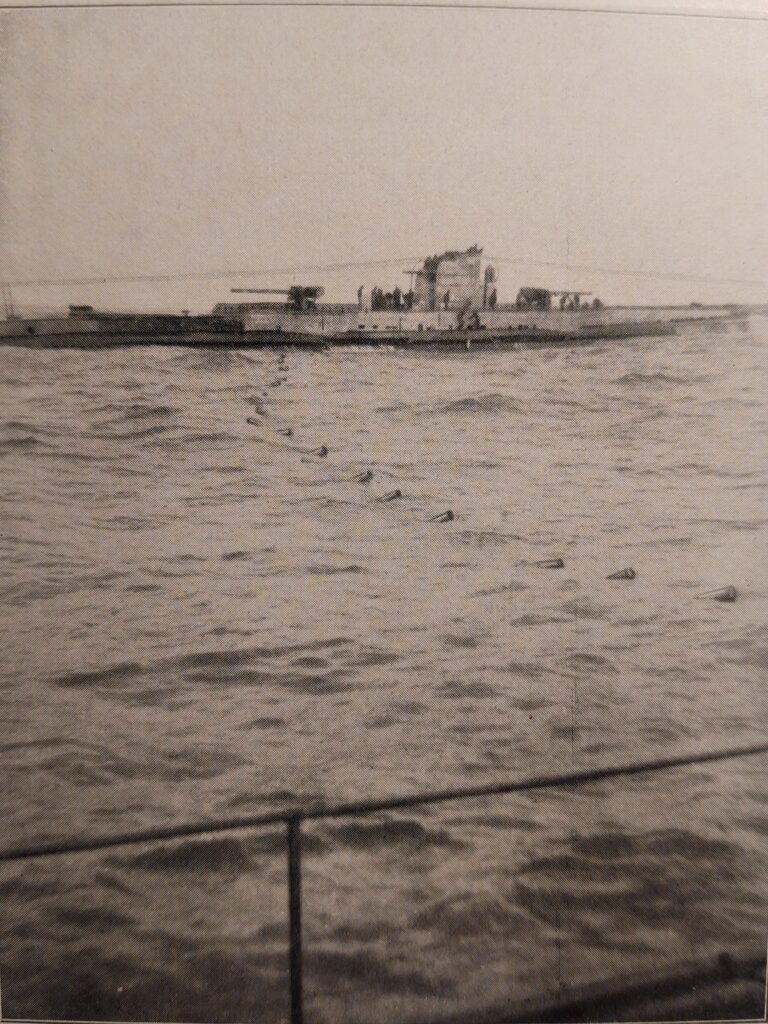

The Germans, however, saw that they had advanced their submarine technology such that their U-boats were capable of striking quite literally anywhere in the world, and wreaking havoc in many different ways, from laying mines to shelling lightships (causing shipwrecks), in addition to sinking vessels with torpedoes, portable explosives and deck guns. The German high command saw U-boats as capable of causing fear and panic among the coastal residents of the U.S. and Canada. After the Battle of Jutland (another encounter in which both sides declared victory), the German surface fleet mostly stayed in port for the duration of the war out of fear of facing the mighty British Navy, but the U-boats proved to be among the most effective weapons for the Central Powers. In just a few years’ time, Germany would go on the offensive again, and submarines would once again be the tip of the spear for their maritime warfare.

There can be little doubt that the Germans ultimately came away holding the upper hand in the World War I submarine war off North America after reading Dominic Etzold’s new book, Reaping the Whirlwind (©2023 Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, Pa., $34.99). This is an outstanding work, and an important book, as it represents the first real telling of this story based upon original German source materials, including U-boat deck logs, war diaries, official German government records, and letters and correspondence from U-boat captains and crew members, most of which represents completely new information. The result is a much more balanced, complete, and interesting telling compared with previous efforts that typically present a U.S.- or Allied-centric view of events, based on primary sources from just one side in the clash.

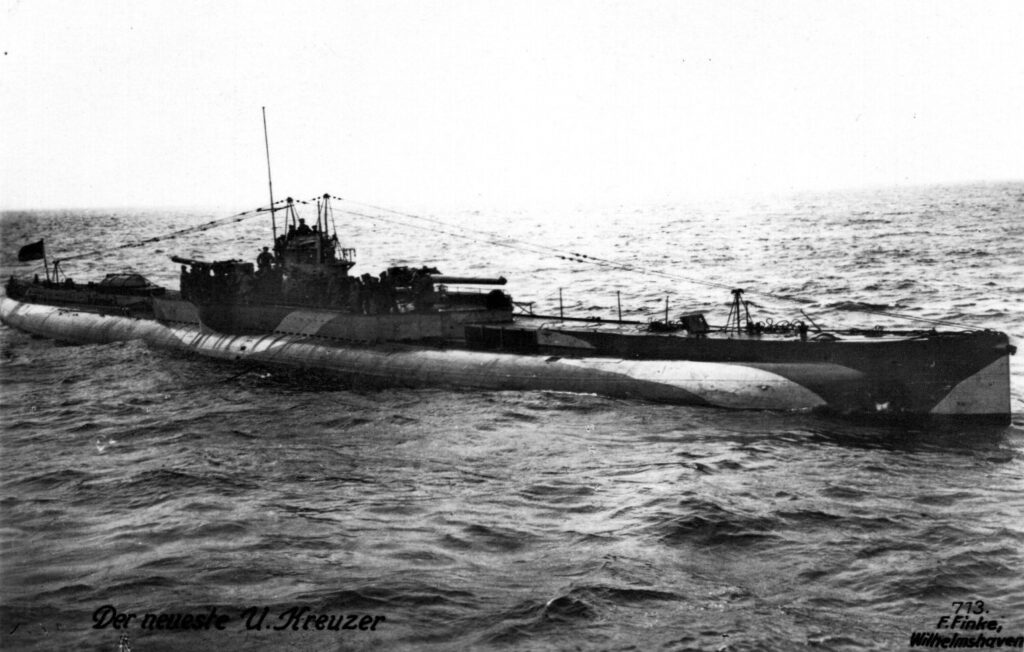

This book focuses on the new class of large ocean-going U-boats that Germany created specifically to be able to reach North America and other far-flung places, well beyond the range of their smaller submarines that were wreaking havoc in European shipping lanes. The first chapters relate the events that led up to Germany’s decision to create submarines that could reach America, and their subsequent decision to embark on a campaign of terror through long-range submarine warfare. Subsequent chapters follow each sub as it puts out to sea all the way through to their return to port at the end of each mission. Accounts of some of these submarines have been the subject of previous books, but this version presents copious facts, quotes, and photographs never before published about all of them. That is why this is essential reading for any serious student of naval history, or U.S. history.

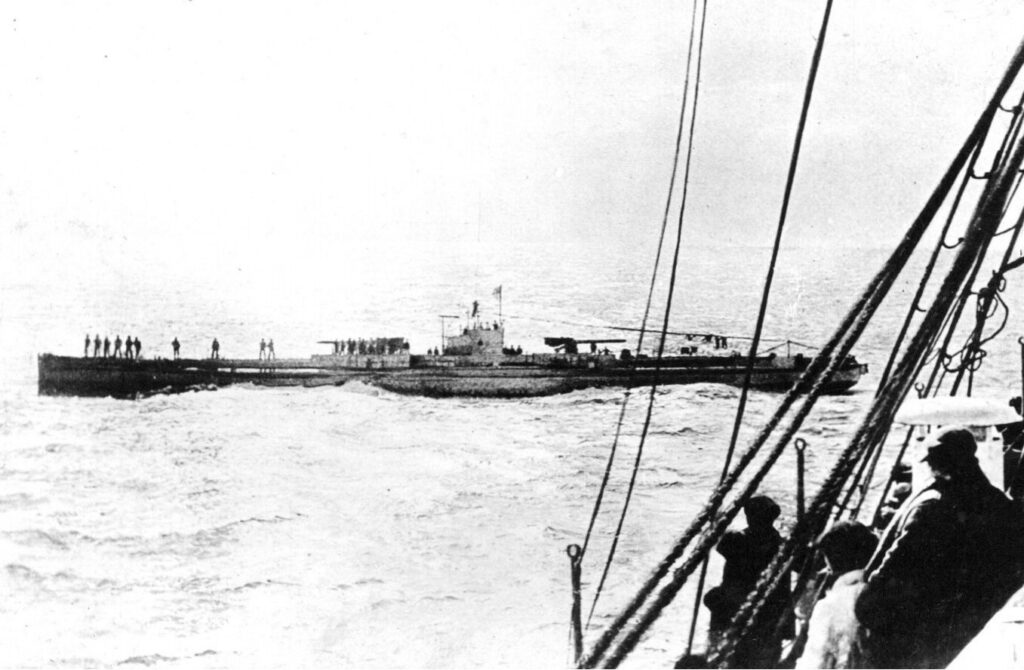

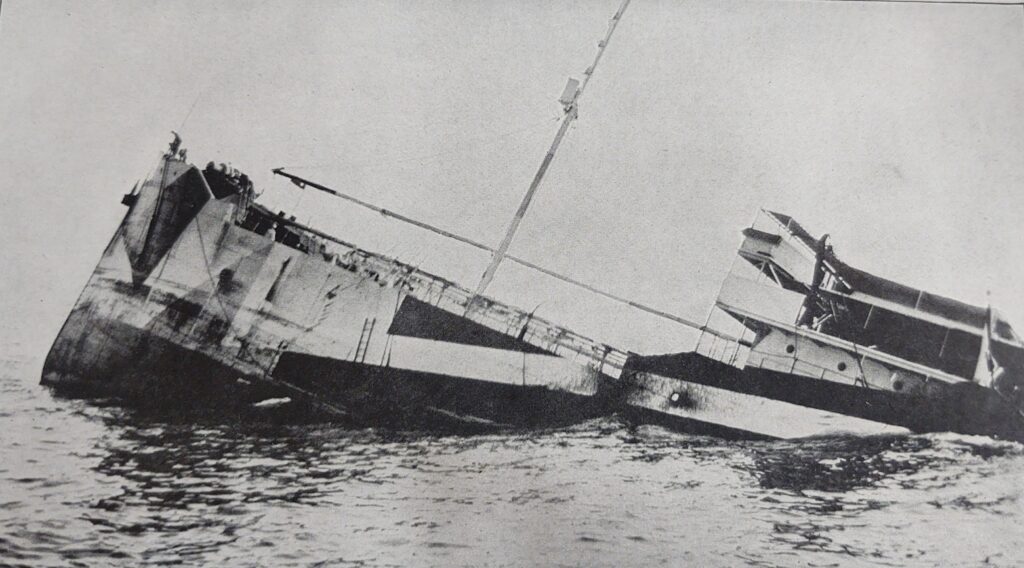

Dismissing the World War I submarine assault on North America as having nominal impact usually results from looking at how small the numbers are: Only five ocean-going German submarines – called “U-kruezers,” or U-cruisers – set out to cross the ocean to attack shipping, and of those, only three achieved something close to their objectives for tonnage sunk. Had the U.S. taken the threat seriously, and adopted almost any kind of meaningful defensive measures, it would have been seen that these U-cruisers were slow, difficult to maneuver, prone to mechanical failures, and susceptible to depth charges or airborne bombs. Owing to the sagacity of the U-boat commanders, and the utter lack of a U.S. response, the Germans operated with impunity and proved that they had the capacity to do significantly greater damage if they chose to engage in all-out unrestricted warfare, where ships were sunk without warning or regard for loss of life. This was the German strategy, to disrupt mercantile shipping as much as possible, creating fear and panic among Americans, all while staying within certain rules of engagement, and as much as possible, avoiding direct confrontations with American destroyers or other naval vessels.

Reaping the Whirlwind provides a lot of fascinating detail about U-boat captains operating according to a kind of code of honor. Targeted ships were warned with a shot across the bow to come to a stop. Once stopped, U-boat “prize crews” typically took a small boat over to the target vessel and inspected it for its contents and papers (at times the target vessel would be ordered to send their captain and papers over to the sub via their own rowboat or tender). The ships had to meet certain criteria before the captains would act. Ships that could prove they were from neutral countries, hospital ships, these were typically allowed to pass without incident. In the other cases, the target vessel’s officers and crew were typically given time to gather their personal possessions, and take to their lifeboats, with food and water, and a compass heading so they could head toward land. First-hand accounts cited by Mr. Etzold show that the submariners consistently demonstrated courtesy toward their victims. In return, German sailors were often portrayed in U.S. newspapers as barbarians and ruthless killers. In World War II, there would be no gentlemanly interplay, any ship thought to be in service to the Allies was typically sunk completely without warning. But that die was largely cast in 1918.

Mr. Etzold’s book is not an introduction to submarines. Other books cover the evolution of underwater vessels in the decades preceding World War I. Other books delve into how incredibly dangerous submarines of that era were, and what a rough duty it was for a sailor to serve aboard such early subs. Any extended time submerged resulted in sailors gasping for breath in foul air; living on brackish desalinated sea water; hard-rationing food at times, and living with the threat of batteries spilling acid that turned immediately into poison gas. Early U.S. submarines were noted for losing entire crews to this sort of accident. But there is little of this in Reaping the Whirlwind. This book will be very well received by students of history who already know a little about the subject, but realize how many unanswered questions have remained. This book helps to answer a great many of these questions, and so its focus is welcome and also helps avoid an unwieldy length.

Indeed, there may yet be another entire book someday just about the utter futility of the U.S. military during this period. The U-boat threat was simply not taken seriously by many American leaders, and the debate about how to counter submarine warfare is a fascinating subject unto itself. For example, Thomas Alva Edison, “America’s Genius Inventor,” was at the height of his worldwide fame when he was approached by the U.S. Navy to help with their submarine battery problems. Following the U-boat sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, Edison perceived the potential threat to America from German submarines, and volunteered to lead a crack team of inventors and experts in a new type of think tank that would be devoted to helping the Navy defend against German submarine warfare.

Edison butted heads with Navy leadership over the location of this new research center, and was ultimately given a Navy patrol boat and a small detachment of sailors and allowed to conduct his own research, while the government sought to set up the think tank closer to Washington, D.C. In the end, Edison provided the Navy with 56 ideas for devices, systems, and weapons, not one of which was accepted and put into use, to his utter consternation. At the same time, the Navy never did get around to building the research facility.

This is just one anecdote that helps illustrate just how futile the American response was, but what Mr. Etzold focuses on is the American strategy of defending harbor entrances, while leaving offshore shipping lanes largely unguarded. Mr. Etzold said in an interview for this review, “I only wanted to focus on the actual defenses in place against the U-boats. If I focused on the experiments on either side, the book would have easily been another 100 pages.”

Reaping the Whirlwind follows on the heels of Hans Joachim Koerver’s The Kaiser’s U-Boat Assault on America: Germany’s Great War Gamble in the First World War (©2020, Pen & Sword Military, Yorkshire, England, U.K.). Koerver also utilizes primary sources, including many from Germany, but his focus is on how the U-boat campaign against America came to be in the first place, with far less emphasis placed on what actually happened. As with most books on this subject, one submarine, in this case SM U-151, is given extensive coverage, while the other four are given much less space, if any at all. This is likewise the case with Paul N. Hodos’s The Kaiser’s Lost Kreuzer: A History of U-156 and Germany’s Long-Range Submarine Campaign Against North America, 1918 (©2018, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, N.C.), and Peter Ericson’s self-published The Kaiser Strikes America: The U-boat Campaign off America’s Coast in WWI (©2008, www.Lulu.com, Morrisville, N.C.).

Reaping the Whirlwind is a great book that could have been even better, with a little more attention to copy editing. The book is organized chronologically, and some chapters are longer than others, and at times the narrative is interrupted with important anecdotes or supplemental information. The simple breaking up of these passage with sub-headings would help the reader understand when the narrative is merely being interrupted, and not turning from one subject to the next.

As is the case with many history writers, including this reviewer, this text tends to prefer two-word constructs to discuss events from the past, while seemingly avoiding the past simple tense. Reaping the Whirlwind doesn’t say much about what anyone “did,” but it is full of what people “would do.” For example: “The torpedo would miss, and yet again another merchant would evade the U-cruiser…” (p. 100). Another: “Ultimately the small convoy would reach France unmolested, and all the vessels would survive the war” (p. 203). The simple past tense would make these and many other such passages less prolix. This unfortunate habit does not detract from the overall quality of the book.

While the references to German sources, documents, and photos are among the book’s main strengths, the handling of translations of German words is inconsistent. Some German words have a simple translation that requires turning to the notes section, others have an adjacent parenthetical translation, still others are included in an appendix of translated German naval titles.

There is also a moment of unintended titillation during one of the more fascinating events of this story, the time that a U-boat apparently engaged in an artillery assault against targets on American land, in the town of Orleans on Cape Cod. On several occasions, a local historian is quoted. But in the very first instance, we hear only of a take on this event from “the author Henry James.” Later we learn that this is not the person considered by many to be “among the greatest novelists in the English language,” author of Turn of the Screw, The Bostonians, and The Portrait of a Lady, but rather a local historian with a keen eye for detail with the same very common name. Only English lit geeks are likely to trip over this.

These very minor nitpickings pale in comparison to the book’s considerable strengths. In particular, Mr. Etzold’s ability to compare American and German primary source materials relating to the same subjects and events show that many of the English-language books published about these U-boat attacks are highly inaccurate, and hew to a rose-colored-glasses view of the U.S. defense. And where there are gaps in those records, or contrarian views without a clear indication of which version is accurate, the author engages in educated speculation that proves to be persuasive as to what most likely happened given the known facts, and this helps complete the narrative.

Another major strength is the book’s illustrations, dozens of photographs of U-cruisers not seen in any of the other books examined for this review. As it turns out, Mr. Etzold, who says that he has a “limited working proficiency” with the German language, has been collecting U-boat pictures and memorabilia for many years, ever since his grandfather fascinated him with stories about the U-boat attacks along the Jersey Shore in World War II. This book – the author’s first – is the culmination of nearly a lifetime of the author’s learning, collecting, and researching this topic.

All of these things help make Reaping the Whirlwind clearly the best book in its class, and a must-have for any serious student of American military history. The failure of American leaders to perceive the dangers from enemy submarines, to learn the lessons from World War I, led to what one historian has called America’s “second Pearl Harbor,” when the Germans returned to America’s coastlines in World War II and operated with impunity for an extended period in which losses of vessels, cargo, and lives, became epidemic. Then, as before, the United States had sowed the wind with obstinance, and once again reaped the furious whirlwind unleashed by German submarines.

About the Author

Dominic Etzold, a resident of New Jersey, holds a degree in history and politics from Drexel University.

John R. Barrows is editor of Monmouth Timeline.

Sources:

Bilby, Joseph G. & Ziegler, Harry. (2016). Submarine War at the New Jersey Shore. The History Press, Charleston, S.C., August 22, 2016.

Ericson, Peter. (2008). The Kaiser Strikes America: The U-boat Campaign off America’s Coast in WWI. Morrisville, N.C., www.Lulu.com.

Gray, Edwyn. (1972). The U-Boat War, 1914-1918. Pen & Sword Books, Yorkshire, England, U.K.

Hodos, Paul N. (2018). The Kaiser’s Lost Kreuzer: A History of U-156 and Germany’s Long-Range Submarine Campaign Against North America, 1918. McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, N.C.

Koerver, Hans Joachim. (2020). The Kaiser’s U-Boat Assault on America: Germany’s Great War Gamble in the First World War. Pen & Sword Military, Yorkshire, England, U.K.

Newbolt, Henry. (1918). Submarine and Anti-Submarine: The Allied Under-Sea Conflict During the First World War. Longmans, Green & Co., London, England, U.K.

Thomas, Lowell. (1928). Raiders of the Deep. Garden City Publishing Company, Inc., Garden City, N.Y.

Leave a Reply