Editor’s note: A complete transcript of Dr. King’s address to Monmouth College is available online here

And an audio recording is available here

On October 6, 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., described by a local newspaper at the time as “one of the most influential negro spokesmen in the United States today,” came to Monmouth County to address the students at Monmouth College in West Long Branch, which today is Monmouth University.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist who became the most visible spokesman and leader in the American civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. King advanced civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi. He was the son of early civil rights activist and minister Martin Luther King Sr. At the time of his visit to Monmouth College, he was president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization formed to provide new leadership for the burgeoning civil rights movement.

King’s speech was held in Alumni Memorial Gymnasium, and was not open to the public due to space limitations. When King’s appearance was announced, The Daily Record predicted that “Most of the college’s 4500 students will be on campus and are expected to attend.” (Editor’s note: Alumni Memorial Gymnasium is now called Boylan Gymnasium and is still on the campus of Monmouth University, next to the bookstore. Enter the University from Cedar Street via the Estate Street entrance and use the visitor’s parking lot there to visit the site of Dr. King’s appearance.)

By October 1966, turmoil had erupted on college campuses across America, from Stanford to the University of Buffalo. Opposition to the war in Vietnam was the primary impetus, but confronting racial discrimination and promoting civil rights were other important aspects of this student movement. Monmouth College was experiencing this upheaval as well.

As King was being introduced by University President Dr. William Van Note, a group of Black students occupied his office in a sit-in demonstration to protest the college’s indifference to discrimination in off-campus housing.

King’s speech was on the topic “The Future of Integration.” He spoke about the history of Blacks in America, and the great strides made by the civil rights movement.

But despite that progress, King cautioned the audience that they were “victim of an illusion wrapped in superficiality.” He spoke of dozens of Blacks who had been murdered that year alone, with no one ever brought to justice. He spoke of Black churches being burned, and of grown white men beating Black children as they attempted to enter an integrated school. The progress of the civil rights movement came at the cost of the blood of many, and complacency threatened to curtail progress unless further action was taken by just-minded people. The country, King said, still had “a long, long way to go.”

“No racial group is an island; all are tied together. When there is injustice, it diminishes all,” he said.

After his lecture, King fielded three questions from the audience. The first came from a Black student representative of the group protesting racial discrimination in housing, and whose members were at that moment occupying the president’s office in protest. They asked Dr. King to visit their protest. King said time constraints would not permit a visit and noted that he lacked specific knowledge of the situation, but he did make a point to emphasize his opposition to housing discrimination in any form. (The protestors and the college ultimately came to agreements regarding housing policies, and the demonstration ended on October 11, 1966.)

Monmouth College Professor Martin A. Watkins, a candidate for United States Congress running on the “Peace and Civil Rights” platform, asked for, and received King’s endorsement. At this, the audience mostly cheered, but boos could be heard as well, “particularly vehemently from Freeholder Marcus Daly,” who was a college trustee. At a faculty meeting later that month, a resolution apologizing for Daly’s behavior was handily defeated.

A student, presumably white, asked Dr. King why Blacks did not do more for themselves, why they needed others to help them achieve success. King adroitly spoke of the great disparity in such things as public libraries in Black communities compared with white, and how such institutional racism has been in place for generations.

“It’s all very well to say ‘lift yourself up by your own bootstraps’ if you have boots. But to say so to the bootless man is cruel,” said King.

Dr. Gilbert Fell, retired professor of psychology at Monmouth College, and an ordained minister, was asked to represent the college and greet King upon his arrival and escort him to the gymnasium for his address. Dr. Fell later recalled that the college’s invitation to Dr. King was not popular in some quarters.

“The college depended on the largesse of the Board of Freeholders who were largely Republican, and they weren’t happy that he got invited,” Fell said. “So his coming was controversial, so controversial, in fact, that it was rumored that William Van Note, the president of the college, was under pressure not to introduce Dr. King before his speech.”

“I went and talked with Dr. Van Note and told him I didn’t see how our college could just ignore the man who was a Nobel Prize winner that fall,” added Fell, an Atlantic Highlands resident. “To his credit, Van Note gave a fine introduction to Dr. King.”

Sentiments ran high because shortly before the speech, King had come out against the Vietnam War, Fell said.

“The atmosphere in the gymnasium became tense and moved toward celebratory because he could really preach,” Fell recalled. “He gave a powerful speech. It began quietly and built up to a crescendo. People were moved. Even those who had come in anger left with a sense of profound respect for the man. Even if you didn’t agree with his position, he had this charisma great leaders always have.”

King clearly made that impression on one newspaper reporter present for his address. G.B. Dyer of The Daily Record said that when one is confronted with “his personality, his logic, his eloquence, there is little room for doubt that one is in the presence of not only a good man, but a great man.” But that great man would become a martyr, dead from an assassin’s bullet, in just 19 months’ time.

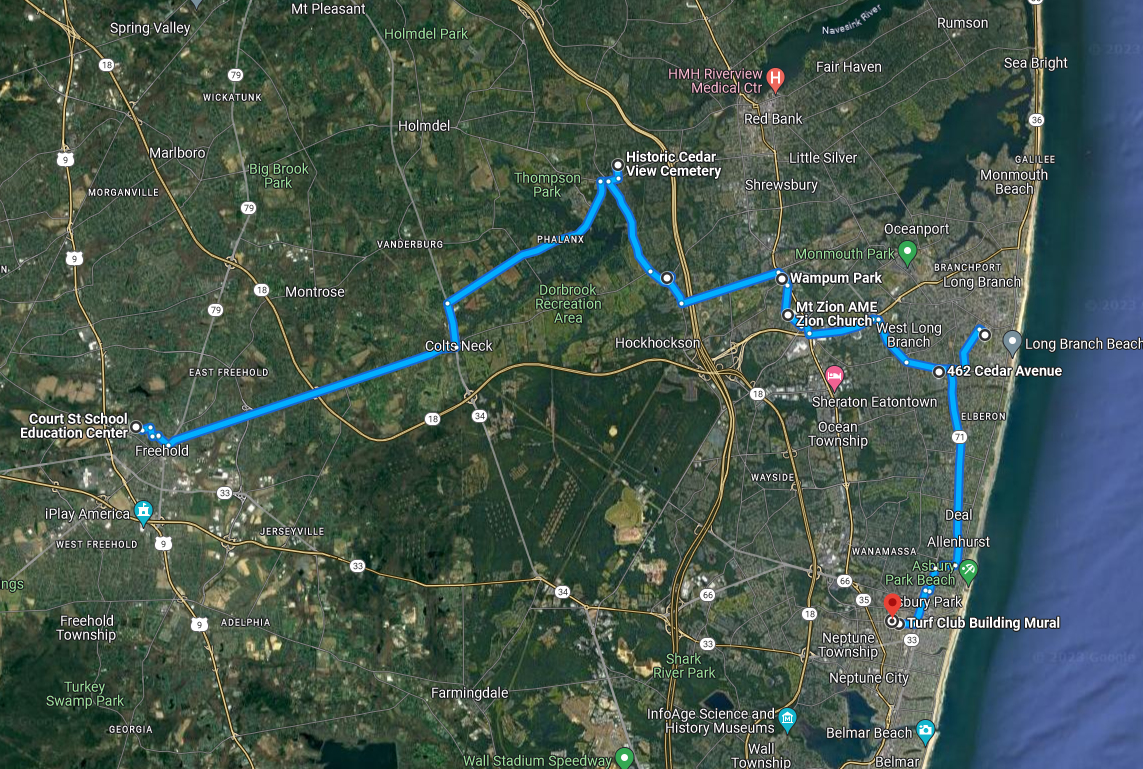

BLACK HISTORY TRAIL: Click here to go back to Day 2, Step 4, the monument to Samuel “Mingo Jack” Johnson. Click here to move forward to the Day 2, Step 6, Long Branch High School Stadium, where football hall of famer Sam Mills played.

Sources:

Dr. Martin Luther King To Speak at College. (1966). The Daily Record, Long Branch, N.J., September 15, 1966, P. 16.

Dyer, G. B. (1966). Dr. Martin Luther King Heard in College Lecture. The Daily Record, Long Branch, N.Y., 1966, P. 1.

Racioppi, Dustin. (2016). A Long, Long Way to Go. Monmouth Magazine, Fall, 2016. Available: https://www.monmouth.edu/about/dr-martin-luther-king-jr/

Stravelli, Gloria. (2003). Remembering a Man and a Movement. CentralJersey.com, January 17, 2003. Available: https://archive.centraljersey.com/2003/01/17/z%E2%80%A2e%E2%80%A2s%E2%80%A2tfor-living-13/

Nobel Lectures, Peace 1951-1970, Editor Frederick W. Haberman, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1972.

Martin Luther King Jr. – Biography. (2021). NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2021. September 23, 2021. Available: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/king/biographical/.

Leave a Reply