Thousands of Black people were the victims of racial terror lynching in the United States between 1865 and 1950, including hundreds of lynchings that took place outside the South. Violent resistance to equal rights for African Americans led to fatal violence against Black men, women, and children throughout the country. Although New Jersey was not part of the Confederacy, chattel slavery remained legal in the state until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, making New Jersey the last northern state to abolish slavery.

After the Civil War, white mobs – emboldened by the ideology of white supremacy and a commitment to white political, social, and economic control – used lynching as the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism. Almost 25 percent of documented lynchings were sparked by allegations of sexual assault, at a time when any contact between a Black man and white woman could be characterized as assault and arouse violent mobs. State and federal officials were complicit in the lawless killings of Black people by failing to prosecute white people who participated in racial terror violence. Locally, law enforcement failed to prevent lynchings and at times incited and participated in mob violence.

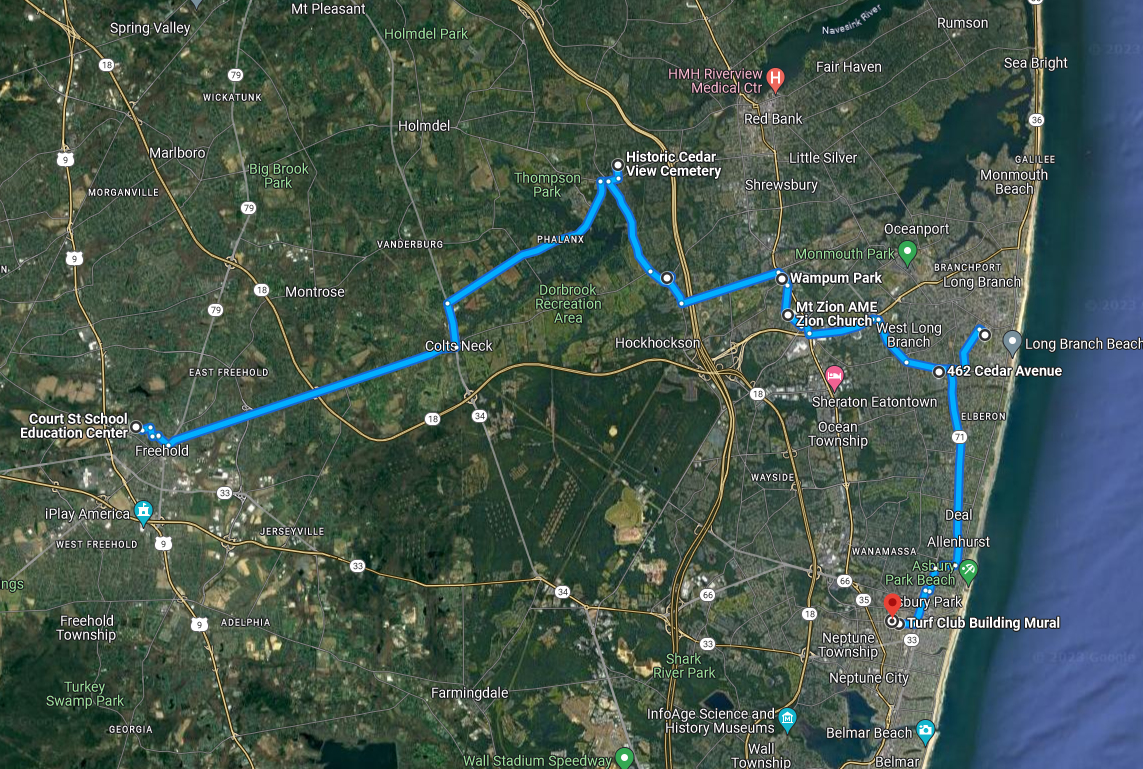

While many of the victims were not recorded by name and remain unknown, at least one victim of racial terror lynching has been documented in Monmouth County, New Jersey. On Saturday, June 18, 2022, a new historical marker was unveiled in Eatontown to commemorate this tragic event. There is free parking at Wampum Park for visitors.

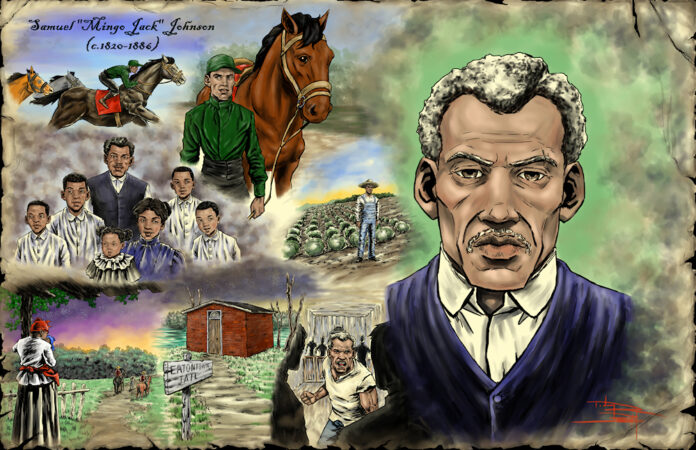

The Murder of Mingo Jack

By Gary Saretzky

On Friday, March 5, 1886, a sickly, 24-year-old white woman, Angelina Herbert (1862-1893), was raped by an African American male in the woods near Whale Pond Brook, south of Eatontown, while on her way to visit a friend, Jackson Brown. Upon reaching the Brown home, she identified the perpetrator as Samuel Johnson, 66-year-old, 120-pound former jockey, known as Mingo Jack because he had ridden the race horse, “Mingo Chief.” Mingo was born in slavery on the farm of Samuel Laird in Colts Neck about 1820 and probably freed in 1845. [i]

Mingo lived with his wife, daughter and several [grand?] children a half a mile from the Herberts and worked as a “rubber” at the Monmouth Park stables. On the same afternoon as the rape, Mingo was arrested at his home by Constable Hermann Liebenthal, who was also said to be the chief of police at Monmouth Park, where Mingo worked. Liebenthal boasted that he didn’t put handcuffs on prisoners because he had a 53-inch chest. Upon hearing the charge, Mingo calmly expressed ignorance of the crime and Liebenthal took him to the jail at Eatontown. The constable then went around town saying that he wouldn’t be surprised if Mingo were lynched before morning. Liebenthal then went home to sleep, leaving Mingo to his fate.

That night, a number of men were at Allen’s saloon in Eatontown; two were seen there tying a noose on a rope. Later, a mob, which may have been as large as 75 men, at least some of whom had been drinking, went to the jail. At about 11:40 p.m., after unsuccessfully trying to shoot Mingo three times through a window, the men broke into the jail, probably using a crowbar one of them found on the railroad tracks nearby and a fifteen-pound sledgehammer taken from Stephen Billings’ marble cutting shop. Mingo’s screams of “murder” were heard by an African American couple, William and Sarah Burford, who lived nearby and, terrified, stayed in their home. Mingo put up a terrific fight and there was blood found in two different cells. He was beaten with two three-foot clubs and one of his eyes was gouged out. According to the medical examiner, he died before he was lynched in the doorway of the jail, but this finding was probably conjectural. His body was found by a six-year-old boy, Dick Stevens, early the next morning.

Ninety witnesses testified at the coroner’s inquest, which was held at the Wheeler House, a hotel owned by Peter Hall, who was said to have provided the rope used for the lynching. The coroner was J.T. Smith of Red Bank, who had cut down Mingo’s body two hours after it was discovered. He was assisted by a Mr. Van Woert, who during the inquest drank liquor from a bottle of cough medicine. Although it was obvious that many of the witnesses had participated in the lynching, none of them cooperated on the witness stand. Henry S. Potter, for example, described in the press as an opium eater, said that, “as a general rule,” he slept soundly from 9:00 p.m. until noon the next day. One of the suspects said to an undercover detective that the lynchers had taken an oath of secrecy.

James Steen, the prosecutor at the inquest, pursued the case vigorously even though threatened with death if he didn’t drop it. Steen (1852-1909) was born in Trenton and graduated from Princeton University at the age of nineteen in 1871. He began practicing law in Eatontown in 1877 and for many years was counsel for the Township. Steen was very active in Eatontown affairs. In 1881, he organized the hat factory and helped organize the Eatontown Fire Department. Two years later, he became the mayor of the borough of Eatontown. Steen also had substantial land holdings in Eatontown, including the saw mill that was very near the jail where Mingo was lynched. Like George Beekman, another prominent attorney of this era, Steen had a passion for local history and he researched and he published a number of articles relating to Scotch immigrants and the Presbyterian Church in Monmouth County. [ii]

At the inquest, Steen, habitually chewing his mustache, was able to elicit from witnesses that Mingo probably was not the rapist. Some witnesses saw Mingo elsewhere near the time of the attack. Moreover, although Mingo’s reputation was not impeccable, Angelina Herbert’s description of the perpetrator’s clothing and hat did not match Mingo’s attire. She recalled that the perpetrator said, “Do you know Mingo Jack?” and it is likely that she took this to mean that he was Mingo Jack when in fact the rapist was someone else trying to put the blame on him. The inquest jury’s verdict decided that Mingo was murdered by unknown persons and that Jacob Coffin, editor of the Eatontown Advertiser, should be rebuked for condoning mob violence in an editorial published the day after the lynching. Subsequently, Frank Dangler, Edward H. Johnson, George Sickles, and William Snedeker were arrested for Mingo’s murder. Dangler, a painter by trade, was a prime suspect since he was seen with nose, throat, and hand injuries the day after the lynching. Johnson, a butcher, had been at Allen’s Saloon the night before the lynching, when the rope was passed around. Sickles was a young farm hand who testified that he walked by the jail around midnight and heard someone scream, “Murder! Murder!” Snedeker, a loafer who seemed to have been spending money even though he didn’t work, was very drunk the night of the lynching and was still drinking the next morning at the primary elections in Oceanport, where he boasted that he had helped pull the rope.

In addition to these four, authorities may have arrested Tom Little, a steeplechase rider whom Snedeker said put the noose around Mingo’s neck. Warrants were also issued for Joseph Anderson and William Kelly, but both of them escaped to New York. Anderson was also wanted for arrest on a charge of assaulting Mingo several months before his death. All the arrested suspects were released on bail and never prosecuted. Constable Liebenthal was also arrested, on a warrant for manslaughter, for not guarding Mingo Jack. He was released on bail and the case was dropped.

The Mingo Jack murder received a great deal of publicity, as it was covered by reporters from both New Jersey and New York City newspapers. Mingo’s death was described as the first lynching in New Jersey since the Revolution. The jail was marked as the site of the lynching in Wolverton’s Atlas of Monmouth County (1889) and picture postcards of it were produced. The building was torn down about thirty-five years ago and the site is now overgrown. The mystery of who really raped Angelina Herbert was never solved and two subsequent confessions only made the puzzle more complex. In 1888, Richard Kearney, on death row for murder, plausibly admitted to the rape, but recanted his confession before his execution. Later the same year, a sailor named John Miller also confessed to the rape before he died of typhoid fever on a three-masted schooner, The Congo, sailing out of New Bedford.

By Gary Saretzky, January 1999. Reprinted by permission from the New Jersey Social Justice Remembrance Committee.

BLACK HISTORY TRAIL: Click here to go back to Day 2, Stop 4: Overlook by the Falls. Click here to move ahead to Day 2, Stop 5, the site of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.s historic speech at Monmouth University.

[i]. Mingo

would have been automatically freed in 1845 at the age of 25, by virtue of the gradual emancipation law passed in 1804, which mandated male slaves to be free at age 25. A journalist reported that Mingo had been freed early because he was “unruly,” but no record of his manumission was recorded in the County Clerk’s Manumission Book. Also, he is not recorded in the Slave Birth Book, which suggests that he might have been born outside Monmouth County.

[ii]. Memorial, Monmouth County Archives.

Sources:

Hodges, Graham Russell. (1997). Slavery and Freedom in the Rural North: African Americans in Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1665-1865. Madison House Publishers, Lanham, Md.

Stone, James M. (2010). The Murder of Mingo Jack. iUniverse, Bloomington, Ind.

The Lynching Case. Continuation of the Proceedings Before the Coroners. (1886). Monmouth Democrat (Freehold), March 18, 1886, P. 2.

Two Frightful Crimes. (1886). Monmouth Democrat (Freehold), March 11, 1886, P. 2 .

“Mingo Jack” Strung Up. (1886). The Daily Register (Red Bank), March 10, 1886, P. 1.

Spahr, Rob. (2012). Lynching of former slave memorialized as ‘low point’ in Eatontown history. NJ.com, September 24, 2012. Available: https://www.nj.com/monmouth/2012/09/lynching_of_a_former_slave_memorialized_in_eatontown.html

Blackwell, Jon. (2008). Notorious New Jersey. Rivergate Books, an imprint of Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, N.J., P. 42-45.

Samuel Laird did not own slaves.

Where was this information derived from?

Is this included on memorial?

In his footnotes, the author states “he is not recorded in the Slave Birth Book, which suggests that he might have been born outside Monmouth County.” So the exact circumstances of his birth are not known. I will reach out to the author for his source on Laird.

First, you’ve made a declarative statement about slave ownership, and have not cited any sources to support your claim. While I wait for Mr Sareztky to respond, I can point you in this possible direction. Graham Russell Hodges’ version of the Mingo Jack story refers to a “Samuel Jackson.” The relevant passage on page 205 reads, “Jackson, formerly the slave of Samuel Laird of Colts Neck…” Source: Hodges, Graham Russell. (1997). Slavery and Freedom in the Rural North: African Americans in Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1665-1865. Madison House Publishers, Lanham, Md.