On November 15, 1775, the former Colts Neck slave named Titus, now calling himself simply “Tye,” took part in the first armed conflict in American history involving an organized unit of African American soldiers. But they were fighting for the British, and their reason for doing so was it promised a path to freedom.

The role of African Americans in the British efforts to quell the colonial revolution was always a tricky question. The British were much more humane and compassionate with respect to bonded labor, but still permitted it in their colonies, where it was the engine that drove economic growth. But Blacks could not serve as uniformed soldiers either in the British regular army units, nor in the Loyalist American brigades. They largely performed manual tasks such as chopping wood, clearing roads, and helping wagons cross rivers and streams. They were called the “Black Pioneers,” and they served with a promise of freedom at the war’s end.

With matters in Virginia in an uncertain state, Lord Dunmore, John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore (1730-1809) and Royal Governor of Virginia (1771-1776), decided to take a calculated risk and demand all residing in Virginia to declare their loyalties, including slaves and indentured servants, and invited all to take up arms against the insurgents.

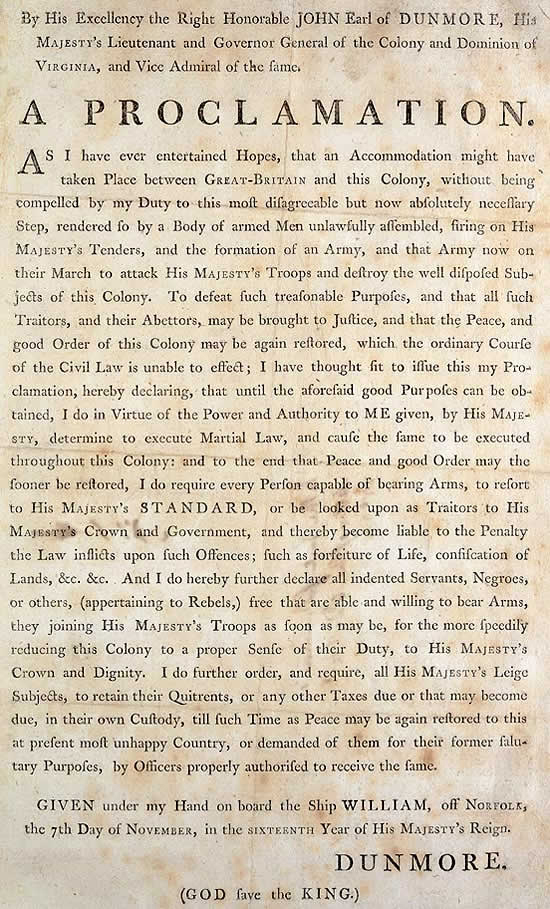

On November 7, 1775, issued a proclamation that was published a week later. In addition to an announcement of martial law, “Dunmore’s Proclamation” read in part:

…the Peace and good Order may the sooner be restored, I do require every Person capable of bearing Arms, to resort to His Majesty’s Standard, or be looked upon as Traitors to His Majesty’s Crown and Government, and thereby become liable to the Penalty the Law inflicts upon such Offenses; such as forfeiture of Life, confiscation of Lands, &. &. And I do hereby further declare all indented Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His Majesty’s Troops as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper Sense of their Duty, to His Majesty’s Crown and Dignity.

He intended to exploit the growing public fear of a general slave revolt or insurrection when issuing his proclamation. Summoning slaves and indentured servants to his Majesty’s standard was a form of economic warfare, denying the colonists a vital source of labor. It was aimed at a significant vulnerability in the economy, social identity, norms, emotions, and ideologies of Virginians and the southern colonies in general. Enslaved persons also provided Dunmore a potential source of military manpower.

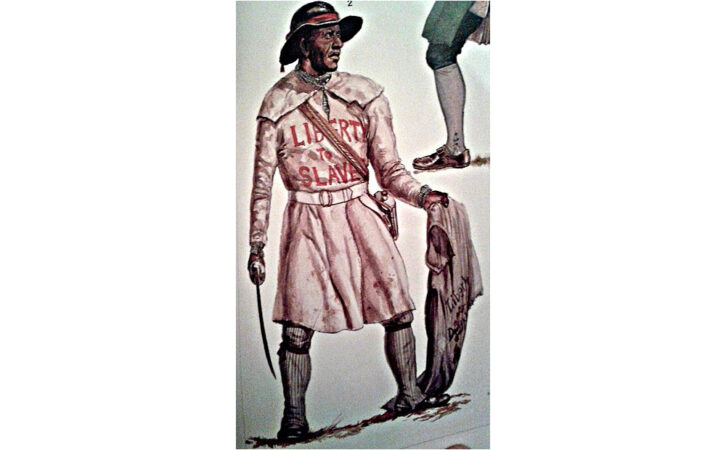

In 1775, Dunmore formed the “Ethiopian Regiment,” made up of slaves seeking an opportunity for freedom. They were not actually from Ethiopia; they were mostly all American-born slaves along with others born in West Africa. During the eighteenth century, “ethiopian” was a generic term to describe anyone with a dark complexion. Dunmore also formed an all-white loyalist regiment. The Ethiopian Regiment consisted of Black soldiers under the command of white officers. Ethiopian Regiment regimental uniforms had sashes inscribed with the words, “Liberty to Slaves” (see picture above). Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment numbered about 300 soldiers during late 1775, and grew to an estimated 850 to 1,400 serving through the summer of 1776.

It is not known how Titus the Colts Neck slave might have learned about these developments in Virginia, but one historian has claimed that after Tye ran away, he first engaged in foraging raids with Loyalists operating out of the British-held Sandy Hook. But from there he might well have been able to find passage aboard a ship headed south. It’s difficult to imagine a fugitive slave being successfully able to cover the 300 miles from Monmouth County to Virginia, mostly through slave states, with a reward for his capture, by land. The gap in time between when he ran away and when he joined Dunmore’s regiment also suggests a mode of transport faster than walking.

The Ethiopian Regiment first saw action on November 15, 1775 at the Battle of Kemp’s Landing, a relatively small engagement that saw Dunmore’s defeat a contingent of militia, capturing two of its leaders. On December 9, 1775, the Ethiopian Regiment took part in the Battle of Great Bridge near Chesapeake, Va. Lord Dunmore saw a growing army of militia gathering and digging in on one side of the Albemarle River and wanted to disperse them. His combined regulars and volunteers charged across the bridge, attacking the militia, who were well-protected by earthworks. They easily fended off the attack and sent Dunmore’s men into full retreat, spiking and abandoning cannon as they fled.

These actions were not enough to prevent Virginia from falling under Whig control. Both the Ethiopian and all-white regiments disbanded in New York after Dunmore’s evacuation from Virginia in 1776. The majority of the surviving Ethiopians who evacuated north joined the Black Pioneers while the white volunteers formed a significant part of the Queen’s American Rangers. One exception was the man now called Colonel Tye, who led a group that became known as the “Black Brigade,” who struck terror throughout Monmouth County in the aftermath of the Battle of Monmouth.

According to one prominent historian, on June 28, 1778, Tye took part in the Battle of Monmouth, and fought with great courage for the Loyalists. Tye captured Captain Elisha Shepard of the Monmouth militia, dragging him across enemy lines, and brought him to his imprisonment at the infamous Sugar House prison in British-occupied New York City.

Tye’s leadership and bravery lead to him receiving the honorary title of Colonel. The British army did not allow Loyalists or blacks to be royal officers, or even uniformed combatants, but a tradition of referring to black military leaders by military rank was a tradition that had begun in other British colonies, e.g., in the Caribbean.

Sources:

Adelberg, Michael S. (2010). The American Revolution in Monmouth County. The History Press, Charleston, S.C., P. 75-97.

Allen, Thomas B. (2010). Tories: Fighting for the King in America’s First Civil War. HarperCollins, New York, N.Y. P. 316-320.

Hannum, Patrick H. (2017). The Battle of Great Bridge: Preserving the Site, Honoring the Soldiers. Journal of the American Revolution, November 27, 2017.

Hannum, Patrick H. (2019). Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation: Information and Slavery. Journal of the American Revolution, December 30, 2019.

Hodges, Russell Graham (1997). Slavery and Freedom in the Rural North: African Americans in Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1665-1865. A Madison House Book, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Md., P. 91-107.

Leave a Reply