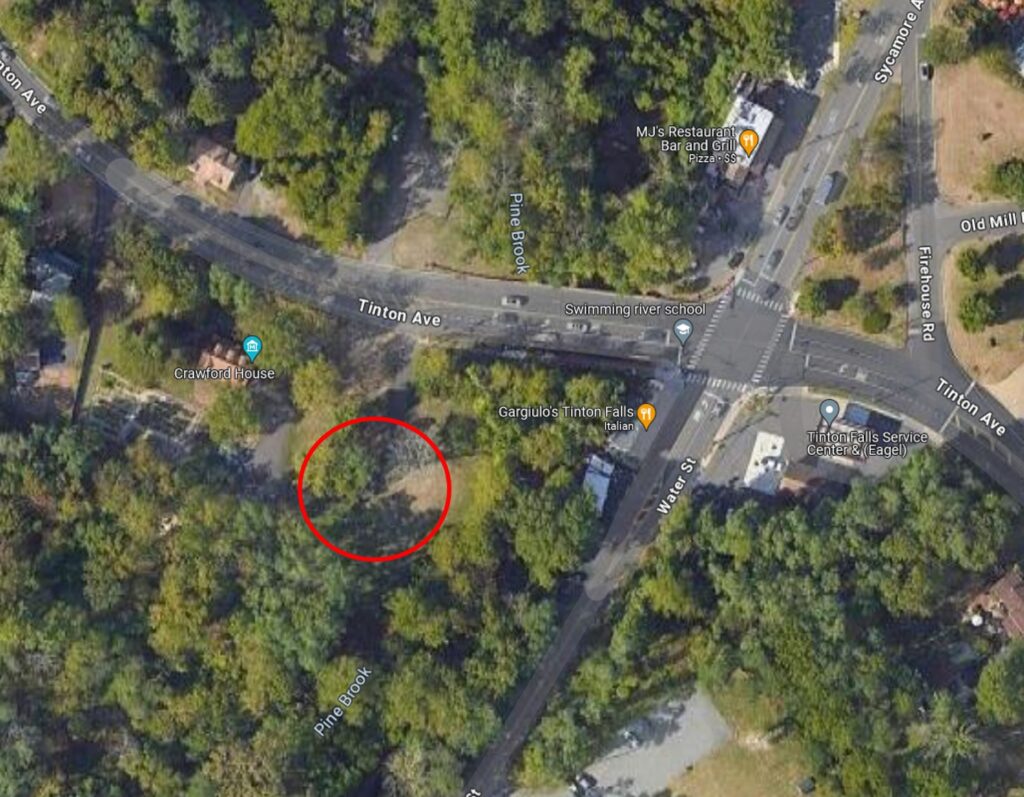

Editor’s note: On December 29, 1675, the entrepreneur Lewis Morris purchased a one-half interest in a bog iron property in Monmouth County near Colts Neck. He built an iron forge on the river in what today is Tinton Falls, and brought slaves in from his Caribbean properties to provide bonded labor. This is the beginning of slavery in Monmouth County. Noted regional historian and author Rick Geffken, a leading scholar into the history of bonded labor and slavery in New Jersey, tells the full story of how our region came to have one of the largest slave populations in the colonies. The burial ground for the enslaved people at this forge is located roughly at 741 Tinton Ave, Tinton Falls, on the grounds of Crawford House, across the street from the row of shops along Pine Brook. Parking is available near Crawford House (see map below).

This article is adapted from his Rick Geffken’s book Stories of Slavery in New Jersey (The History Press, 2021), available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Costco, and other retail booksellers. For a personally signed copy, contact the author via email at [email protected].

by Rick Geffken, copyright ©2022

The entrepreneur Lewis Morris brought slaves to an East Jersey ironworks in 1675, but he was not the first to introduce slavery to the Jerseys. Dutch traders had forced Africans to work their Bergen plantations fifty years earlier. Still, the sheer scale of Morris’s use of chattel slavery was new to the colony. He brought dozens of enslaved workers from his sugar cane plantation in Barbados. They toiled on his Tinton Manor estate, located in what he would christen Monmouth County. Both his estate and the county were named for the Morris family seat in Tintern, Monmouthshire, Wales.

Lewis and his brother Richard Morris were already successful sugar planters when they took advantage of the opportunity to expand their fame and fortunes in the English colonies two thousand miles to the north on the Atlantic Coast.

After Peter Stuyvesant surrendered Dutch New Amsterdam to Colonel Richard Nicholls in August 1664-65, the Englishman renamed the promising seaport New York for James, Duke of York, his patron. In 1668 the Morris brothers partnered on a 520-acre tract in what had once been Jonas Bronck’s land east of Harlem Creek. They called the plantation Morrisania. A section of the Bronx retains that designation to this day.

Lewis Morris also owned a house at the southern tip of Manhattan, next door to one of New York’s most prominent merchants, Cornelius Steenwyck, who made his money selling tobacco, salt, and slaves. The two ambitious men became friends and sought business deals together. By 1672 Steenwyck was on the governing Council of New York. He later served two terms as mayor.

Lewis Morris, not ready to abandon living at his West Indian plantations despite a collapse of the sugar market, returned to Barbados. The deaths of both Richard Morris and his wife Sarah in 1672, caused Lewis to go to New York once again to administer to their estate, and, not inconsequentially, to care for their infant son named after him, Lewis.

In 1674-75, Lewis Morris joined Cornelius Steenwyck in financing a bog iron mill in Shrewsbury, East Jersey. James Grover, Richard Hartshorne, and John Bowne had started the iron works and needed additional capital to keep the enterprise running. The two New York investors were eager to expand their influence and fortunes.

Back in Barbados, a slave conspiracy to murder their masters was discovered in 1676, a week before it was to be conducted. White European planters and island authorities put this plot down brutally – suspected conspirators were “burned alive, beheaded, and otherwise executed for their horrid crimes.” The island government proposed that none of the “rebellious negroes” could be bought or sold, afraid the contagion would spread elsewhere. The potential economic loss was another reason for Lewis Morris to ship dozens of his slaves to East Jersey. He had another business incentive as well.

As the late noted scholar Giles Wright wrote “Because West Indian slaves were familiar with Western customs and work habits, they were highly prized in New Jersey, where master and slaves usually worked and lived in close proximity.” When Lewis Morris decided to bring his slaves north with him, he knew their capabilities well, especially that of one particular man, as we shall see.

Extant Morris Iron Works accounting records from 1676 list expenses for building a “negro house” on the property. A contemporary map calls it a cellar, no doubt a primitive shelter for the first enslaved men brought here. The building, whatever it was, was separated from the “white man’s house” where paid workers lived.

Lewis Morris eventually took over complete ownership of the iron works and purchased additional surrounding lands, eventually accumulating 6,200 acres. He was well on his way to becoming the richest man in East Jersey thanks to the mill’s production of valuable bar iron, his mercantile interests in New York, and his trading contacts in the Caribbean.

A 1679 description of what Morris owned in East Jersey notes “There is within its jurisdiction Colonel Morice (sic), his Mannour, being about six thousand acres, wherein are his iron Mills, his Mannours, and diverse other buildings for his servants and dependents there, together with 60 or 70 negroes, about the Mill and Husbandries, in that plantation.”

The iron mill was located on the “Falles Creek,” now known as Pine Brook, a tributary of the Swimming River. Well into the 21st century, the Tinton Falls area called Pine Brook continued as an African-American community. No contemporary Pine Brook family has self-identified as descendants of Morris slaves despite the likelihood.

An interesting aspect of Lewis Morris’s early life is that he was a Quaker. Despite our modern perceptions, early Quakers were not abolitionists. He became a member of the Society of Friends (the sect’s formal name) in Barbados. Quaker proselytizers often visited the island looking for converts. Morris was swayed by their appeal to former soldiers disillusioned by war. He and his brother had played active military roles in the mid-century English Civil Wars. In any event, Lewis Morris was described as a “severe Quaker.”

The Morris bothers had originally supported the Parliamentarians. Lewis switched sides and advised Admiral Sir William Penn during naval actions in the Caribbean. Lewis Morris saw enough futility, death, and destruction during wartime, and impressed by visiting Quakers, he embraced Quaker tenets. Admiral Penn was the father of the William Penn who founded Pennsylvania.

At his death in 1690-91, the inventory of Lewis Morris’s properties listed sixty-six enslaved men, women, and children valued at £844, the equivalent of over $2.3 million today. His two plantations (Tinton Falls and New York) were valued at £6,000 ($16 million plus now), so the Morris slaves made up almost 15% of his estimated worth (we don’t know exactly how many of slaves lived in each Morris plantation. Some of the more skilled may have worked in both). A private inventory of slaves made by the nephew Lewis Morris indicated there were actually twice as many slaves, and thus would have represented just short of a third of the total value of Morris’s holdings. Even that higher estimate undervalues the true worth of these Black men and women to the Morris family in the last years of the 17th century. The Morrises could not have attained their great wealth without the literal blood, sweat and tears of these enslaved human beings, a contribution both extraordinary and incalculable.

Princeton University’s John Strassburger wrote in his 1976 doctoral thesis “Lewis Morris inherited more slaves than the total number owned by anyone else then living in New York or New Jersey. Even in Virginia, Morris would have qualified as a large slave holder.” The sixty-six inventoried enslaved people were 60% of all the slaves in East Jersey in 1691, according to researches done by Colgate University scholar Dr. Graham Russell Hodges.

A confounding aspect of the Morris family relationship to slavery involves George Keith. A Scottish Presbyterian by birth, Keith was an early convert to the Religious Society of Friends. He travelled on missions with Quaker founder George Fox and William Penn. In 1685, Keith was appointed Surveyor-General of the East Jersey Province and was rewarded with a huge tract of Monmouth County land for his efforts.

During this period, the senior Lewis Morris hired Keith to tutor his nephew. Just two years after the death of the older Morris, George Keith published An Exhortation & Caution to Friends Concerning Buying or Keeping of Negroes which is considered an early abolitionist tract. In this searing document, Keith argued for observance of “that Golden Rule and Law, To do to others what we would have others do to us.” He advocated setting the enslaved free and educating their children. Quite a different view from that of both Lewis Morrises.

Keith and the younger Lewis Morris remained so close that when Keith converted yet again, this time to Anglicism, the pair began to hold religious services at Tinton Manor. In fact, Christ Church Shrewsbury, only a few miles east of Morris Manor, considers the two men among the founders of their parish. Despite all Keith believed and taught about the inherent evil of slavery, there are no records indicating that either Lewis Morris ever freed their slaves. The profit motive overrode any religious and moral rationale they may have held.

Over and above any monetary value the Morrises realized from their chattel slaves, the influence of the two men in the very early formation of New Jersey commerce allowed the concept of owning Black human beings to become a deeply entrenched and socially-accepted practice. In effect, the success of the two Lewis Morrises gave imprimatur to others who wanted the status and prestige of holding Black people in bondage. Slaveholders thought of their enslaved men and women strictly as machines to generate profit.

The enslaved who created great wealth for Tinton Manor did so through back-breaking labor. Abetted by white indentured servants, the slaves worked at two mills on the property along the Falles Creek. A sawmill turned lumber culled from the thousands of acres of surrounding forest into boards for use on the Manor and for export to New York markets. A grist mill produced flour from the acres of wheat, rye, barley, oats, and corn. The slaves planted, tended, and harvested these crops. Some of these enslaved were valuable because of the agricultural skills learned in the sugar cane fields of Barbados. Other slaves learned the art of iron forging from experienced white iron mongers from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Henry and Samuel Leonard. Originally contracted by James Grover, the Leonards directed enslaved workers in the dangerous and heavy work required to make the valuable bar iron.

Treated as efficient and inexpensive semi-human devices, the enslaved worked long days and nights with minimal sustenance to keep them going. That “negro house” would have been rudimentary – slaves resting on a dirt floor with some hay or straw to ease their weariness. They would get barely tolerable foodstuffs and whatever they could grow, or steal from Morris’s grain fields. Many died from exhaustion – no matter, they were replaceable.

The enslaved also became good animal husbandmen tending to Tinton Manor’s variety of cattle, pigs and hogs, sheep, and horses. These chattel slaves would have milked cows and made cheese for the Morris family, consuming what little they could for their own survival.

We can infer that enslaved women performed domestic and agricultural tasks, and any other jobs deemed below men’s work. The women were abused as sexual objects for the satisfactions of the men controlling them. Like slaveholders everywhere, Morris understood that the easiest and least expensive way to increase his labor supply was by forced propagation. If Morris himself never participated, he’d look the other way at the behavior of his white workers who would have seen this sexual exploitation of enslaved women as part of their entitlements. Not for what it really was. Rape.

How did the senior Lewis Morris regard his slaves? We can only speculate. The younger Lewis Morris was more forthcoming. He believed his Black enslaved were people, just not equal to white people. In a 1730 letter to his son, manager of Tinton Manor, he cautioned John Morris “not to Trust negroes” because “they are both stupid and conceited and will follow their own way if not carefully looked to.”

Copyright©2022 by Rick Geffken

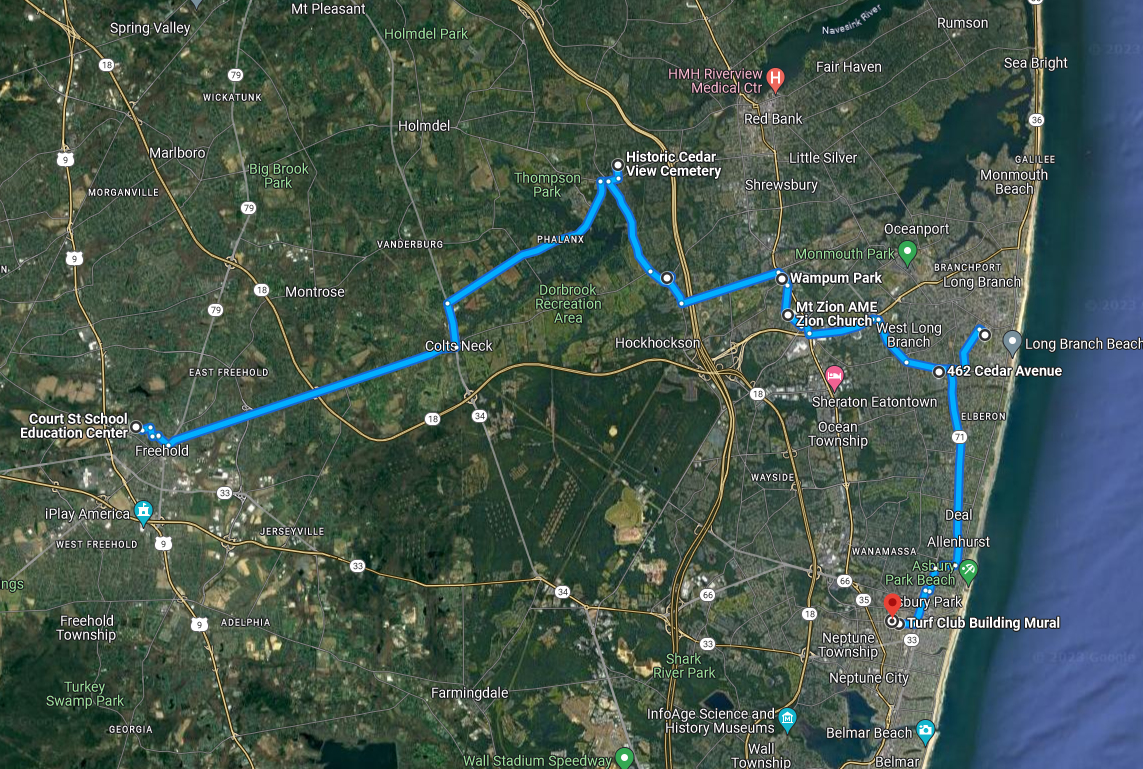

BLACK HISTORY TRAIL: Click here to go back to Day 2, Step 2, Cedar View Cemetery. Click here to move ahead to Day 2, Step 4: Memorial to Samuel “Mingo Jack” Johnson.

About the Author:

Rick Geffken has written numerous articles on various aspects of New Jersey history for local newspapers, magazines, historical societies, and newsletters. Rick has presented historical papers at the New Jersey History & Historic Preservation in 2014 and 2015. He has participated in Symposia for groups such as the Navesink Maritime Historical Association, and he has appeared on the New Jersey Cable TV show, Family Historian.

Rick’s books include The Story of Shrewsbury Revisited, 1965-2015; Lost Amusement Parks of the North Jersey Shore; Highland Beach, Gateway to the Jersey Shore, 1888-1962; Hidden History of Monmouth County; and To Preserve & Protect, profiles of people who recorded the history and heritage of Monmouth County, New Jersey. The History Press will publish Stories of Slavery in New Jersey in January 2021.

Rick has spoken about New Jersey historical topics – Lost Amusement Parks; Quakers & Slavery in NJ; NJ’s Submarine Inventors: Simon Lake & John Holland; The Morris Family of NJ – at dozens of historical societies and libraries. He has been a featured speaker at the Trent House Museum, the Quaker Meeting of Shrewsbury, the Battleground Historical Society, and other organizations. He is a Trustee of the Shrewsbury Historical Society; a Board member of Truehart Productions (film company) and the Friends of Cedar View; Past-president and a Trustee of the Jersey Coast Heritage Museum at Sandlass House; and a member of the Monmouth County Historical Association.

Rick is currently heading up a project called the New Jersey Slavery Records Index under the auspices of Monmouth University of West Long Branch, NJ. He is an active member of the New Jersey Social Justice Reconciliation Committee.

Rick retired from a career with Hewlett-Packard; owned and operated several small businesses; taught secondary school mathematics; and was an Adjunct Professor at Ocean County Community. A retired U.S. Army officer and Viet Nam veteran, he holds a BS in Economics from St. Peter’s University, a Secondary Teaching Certificate from Monmouth University, and an MA in Social Sciences from Montclair State University.

Partial List of Sources:

Geffken, Rick. Stories of Slavery in New Jersey. The History Press, Charleston, SC, 2021.

Barrett, William A. Ed. Historical Scrapbook of Tinton Falls New Jersey. Tinton Falls Bicentennial Committee, Tinton Falls, 1976.

Lewis Historical Publications. History of Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1664-1920. New York, NY: Lewis Historical Publications, 1922.

Mandeville, Ernest W. The Story of Middletown, The Oldest Settlement in New Jersey. Middletown, 1927.

Mulholland, James A. A History of Metals in Colonial America. Univ. of Alabama Press, 1981.

New Jersey State Archives. East Jersey Proprietors’ Records, et al.

Salter, Edwin & Beekman, George. Old Times in Old Monmouth, Historical Reminiscences of Old Monmouth County, New Jersey.

Smith, Samuel Stelle. Lewis Morris, Anglo-American Statesman ca. 1613-1691. Atlantic Highlands, NJ, 1983.

Stillwell, John E. Historical and Genealogical Miscellany, Early Settlers of New Jersey and their Descendants, Vol. III. NY, 1914; Vol. V, 1932.

Stillwell, John E. The Old Middletown Town Book, 1667 to 1700; The Records of Quaker Marriages at Shrewsbury, 1667 to 1731;

The Burying Grounds of Old Monmouth. New York, 1906.

Stuart, Andrea. Sugar in the Blood. Vintage Books, New York, NY, 2012.

Whitehead, William Adee, and Morris, Lewis. The Papers of Lewis Morris, Governor of the Province of New Jersey from 1738 to 1746, Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, Vol. IV. Newark, NJ, 1852.

Rick. Great article. I am researching my family genealogy and hoped you might know something. Could you email me please. Thank you.

Very interesting seeing so many familiar names from early Monmouth County history appearing in one another’s histories (Grover, Hartshorne, Bowne, Keith, etc.), although I suppose such a degree of interaction should be expected given the size of the population at the time.

As for the following segment from the text, beginning with “Over and above any monetary value the Morrises realized from their chattel slaves…” and ending in “Rape” (total 5 paragraphs), is this information derived from direct sources (contemporary records, letters, biographical information, etc.)? If so, much of this portion of the text could benefit from citations, without which it reads like speculation.

For example, with respect to the finer details of the overall image that is being presented of Lewis Morris (working his slaves to death by exhaustion, keeping them on the brink of starvation, raping and/or facilitating rape of the women), do contemporary records exist that confirm that these events took place at Tinton Manor, that this was in fact how Morris treated his slaves? Or is the reader meant to understand that these aren’t actually events which are known and proven to have taken place, but rather, assumptions of the kind of events which may have taken place (no doubt based on your personal opinion of the character of Lewis Morris, as informed by your research of his personal writings and other contemporary accounts of his life and character)?

It was also interesting to read that early Quakers were not abolitionists, which is certainly something new that I’ve learned. (I was also under the impression that Quakers have historically been abolitionists, and that this was a factor which strongly contributed to Pennsylvania becoming the first state to end slavery due to its historical Quaker influence). Perhaps you should do an article sometime about the evolution of Quakers, and how and when they came to be such a powerful voice in the abolitionist movement?