By John R. Barrows

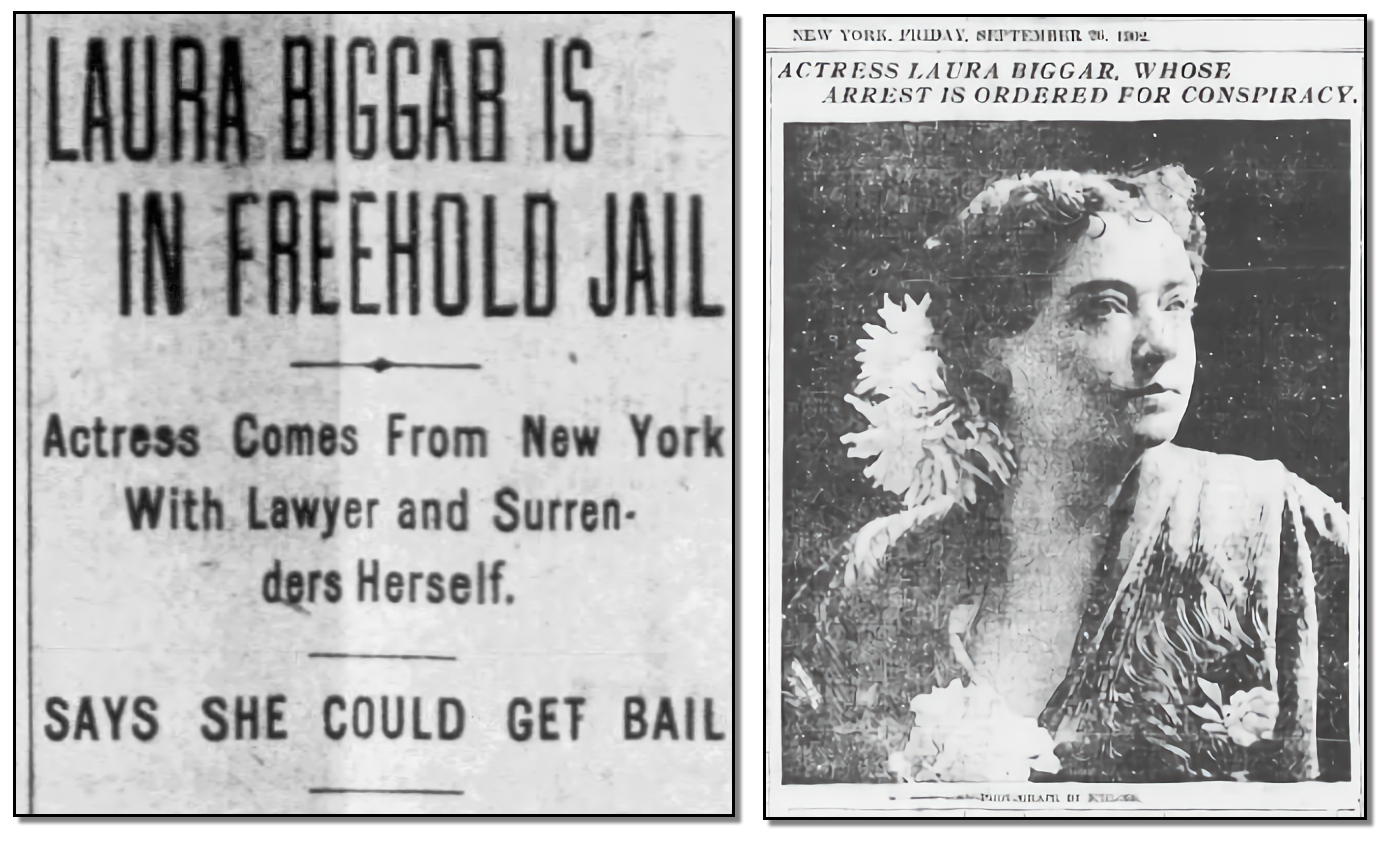

On November 4, 1902, nationally famous vaudeville stage actress Laura Biggar surrendered herself to Monmouth County authorities in Freehold, where she was placed under arrest, arraigned, and confined to the county jail there. She had arrived from her home in New York City with her attorney, Samuel Frankenstein. According to the Asbury Park Press, “Miss Biggar seemed at ease and walked unconcernedly with her lawyer to the sheriff’s office.” A crowd gathered around hoping to get a glimpse of the woman claiming to be the widow of Henry Martyn Bennett, millionaire owner of the Bijou theater chain and the Windsor Stock Farm horse ranch in Farmingdale. Biggar was facing charges along with her doctor/lawyer and a justice of the peace of conspiracy to commit fraud, a crime that allegedly involved a sham marriage, a baby’s corpse, a Bayonne sanitorium, and an odd clause in New Jersey’s inheritance laws. For most of the first decade of the 20th century, the nation’s newspapers were breathlessly focused on the sensational and scandalous happenings in Monmouth County.

Who WAS Laura Biggar?

Laura Bigger was born in Delaware in 1866, the only child of Joseph and Jane Bigger. Although she claimed in later interviews that her parents were wealthy, they seem to have been a modest working-class family, her father a carpenter, e.g. She changed the spelling of her last name to Biggar after she began her acting career. From the very beginning, she had a penchant for self-promotion and exaggeration.

In 1876, 10-year-old Laura appeared in charades in Delaware City, playing her part “in a manner truly wonderful for one of her age” according to a local paper. As a teenager she sang and gave dramatic readings in student recitals and charity concerts in Wilmington and nearby towns. By 1884 she was appearing in Philadelphia in light operas such as Princess Ida. She performed with several touring companies, primarily on the west coast.

In 1886 she married James W. McConnell, a fellow actor, in Winnipeg, Manitoba. They had one son, J. W. McConnell Jr., and eventually divorced, but continued touring and performing together. By 1887 she and McConnell had joined producer William A. Brady’s touring company, initially playing supporting roles in the musical stage productions of After Dark and Sir Henry Rider Haggard’s She. By 1890 she was playing the lead in Brady’s production of The Clemenceau Case, a popular melodrama with a scandalous nude modeling scene.

In 1892 she began appearing in her most successful role, as the lead in the hugely popular musical, A Trip to Chinatown. This show was so popular that at one point there were two productions running in New York City at the same time, as well as multiple touring shows.

Laura starred with Bert Haverly, a popular actor. Biggar and Haverly were reported to be married, although Haverly would later deny it. They toured together throughout most of the 1890s.

While in Pittsburgh performing in a vaudeville performance, Biggar met, and eventually moved in with Henry M. Bennett, a married millionaire some 40 years her senior, who owned a chain of theaters and various hotel properties in New York and New Jersey.

Who WAS Harvey M. Bennett?

Henry Martyn Bennett was born March 2, 1831, in Burlington, Vermont. He made money investing in a New York City hotel, and by serving as a sutler, or supplier to the military, during the Civil War. In 1870, he moved to Pittsburgh and was elected president of the Consolidated Gas Company. He became interested in theaters and owned Bijou playhouses in Boston, New York, Baltimore, Brooklyn and Pittsburgh. At some point in the 1880s, he purchased land in Farmingdale, N.J., and began operating a horse ranch called the Windsor Stock Farm.

On May 24, 1897, Laura Biggar and Bert Haverly starred in a new show titled, She Would Be an Actress, which opened (to disappointing reviews) at the Hopkins-Duquesne Theater, owned by Henry Bennett, where he first met the actress. Although married, Bennett was clearly infatuated with Biggar, such that it aroused the ire of Haverly, who reportedly sued Bennett for alienation of affections, but in the end won only a legal separation.

On October 13, 1897, Bennett’s wife Frances passed away. She was interred at the Mount Prospect Cemetery in Neptune, where her husband erected a seventy-five-foot-high monument that still towers over the cemetery today.

Over the years, Bennett made millions in gas and entertainment, and then sold his theatrical interests outside of Pittsburgh and became a full-time horse rancher in Farmingdale. Biggar and Bennett were living together during this time, Bennett said to have been in very poor health.

On April 9, 1901, a newspaper report stated that Bennett had made out a new will before undergoing surgery to amputate his leg, which had become gangrenous resulting from an ingrown toenail. The New York Times said that Laura Biggar had “nursed Bennett back to life when it seemed almost impossible that he could live.” She was described as “a blonde of medium height” at the time of Bennett’s death.

Henry Bennett died “of dropsy,” (an obsolete term for the swelling of soft tissues due to the accumulation of excess water) on April 4, 1902, age 71. Bennett’s coffin was said to be “the most expensive one ever used in this vicinity.” At the time of his death, his Windsor Stock Farm in Farmingdale was valued at $200,000, the horses valued at $50,000, one horse alone worth $10,000.

After Bennett’s death, newspaper reports including The New York Times immediately leaked that he had left Laura Biggar the majority of his fortune. Bennett’s only relatives, a niece and nephew and a third distant family member, all from Boston, quickly hired lawyers and announced that they intended to challenge the will, claiming that Biggar had come into her inheritance via “undue influence.”

Thus began a courtroom drama that would play out over the next decade on the front pages of newspapers across America. Each week, new sordid details emerged, lawyers from all sides played their angles in the press, and it would have a shocking conclusion.

The Courtroom Battle for Henry Bennett’s Millions

On April 14, 1902, Henry Martyn Bennett’s will was read in Asbury Park, and while the details were not confirmed until later, The New York Times reported that “the larger portion of the estate” was left to “a former star of the stage named Laura Biggar.” The size of the estate was estimated at about $1,500,000, which would amount to more than a half a billion dollars in today’s currency.

Bennett’s will included bequeathals to his brother-in-law, his secretary, and his former business partner, while Biggar inherited New York City properties at 119 East 83rd Street and on 56th Street, four tenements on Second Avenue and 72nd Street, and all of the jewelry, household furnishings, and personal belongings of the late Mrs. Frances Bennett. Probate hearings began in Freehold, but were soon moved to Red Men’s Hall in Long Branch. As part of normal proceedings, Biggar appeared before the judge and asked that the will be approved and probated, and denied any undue influence.

On June 23, 1902, the Asbury Park Press reported that Laura Biggar “has been living for some time at Dr. Charles C. Hendrick’s sanitorium on Avenue A, Bergen Point (Bayonne)…Dr. Hendrick, who is also a lawyer, will represent Miss Biggar” in her inheritance claim. Newspaper reports covering this sensational case sometimes identified Hendrick as “Hendricks,” “Kendrick,” or “Kendricks” at various times. Hendrick, a graduate of Seton Hall College, was married and a father of three, and also worked as an inspector for the Hoboken board of health.

On August 16, 1902, the Asbury Park Press ran a large headline asking, “Were Laura Biggar and Bennett Wedded?” and a subhead reading, “Arrival of Little White Casket Supposed to Contain Body of her Dead Child and this Causes No End of Gossip and Speculation.”

It seems that earlier that week, a Monmouth County undertaker had received a telephone call from a Bayonne undertaker, asking the former to receive the body of a child to be interred at Mount Prospect Cemetery next to Henry and Frances Bennett. When the casket arrived, it bore an engraved plate that read, “Henry M. Bennett, died August 13, 1902, age 15 days.”

A lawyer for the executors of the estate moved for and was granted an immediate order forbidding the opening of the Bennett lot.

Observers immediately cast suspicion as to what was really behind these new developments – a Bennett-Biggar marriage and child. “Lawyers who are acquainted with the circumstances as related say that in case there was a marriage between Bennett and Laura Biggar, and that child was born after the making of the will, that instrument, unless it made some provision for the birth of the child in its contents, would be null and void.”

This was a peculiar notion in New Jersey state law that only applied in the rare circumstances wherein a man fathered a child, and the father died, and the child was not mentioned in the will. In these circumstances, per state law, the child heir inherited everything, regardless of what was in the will. And if the child then died, the mother inherited everything from the child. Through this gambit, Laura Biggar would have an even larger claim over the Bennett estate.

On September 12, newspapers reported that Biggar had presented the court with affidavits that she and Bennett had been married on January 2, 1898.

A week later, Friday, September 19, Samuel C. Stanton, a justice of the peace from Hoboken, took the witness stand and testified that he performed the marriage ceremony for Biggar and Bennett on January 2, and identified the marriage certificate he had signed. Stanton, a law clerk and city health inspector, “appeared to be a disconcerted witness,” according to one onlooker. He testified that he had been “routed from his bed” at 11 p.m. by Biggar to perform the ceremony. Despite his wife and daughter being present nearby, Stanton went elsewhere to find a witness for the ceremony, a Mrs. Anna Weber (some reports named her Webster or Webber), whose name was on the marriage certificate, signed in a clearly different hand and different color ink.

A Flimsy Story

Stanton then said that Mrs. Weber had since died. He then told a curious story about what happened to the original marriage certificate. At that time, in Hoboken, marriage certificates were filed with the city board of health. Stanton was employed as an inspector by the health department, and so was present in their offices on a regular basis, just six blocks from his residence. Yet in his sworn testimony he said that he had sent the certificate to the department to be filed via the mail, and it had never arrived, and was now considered lost. He also testified that the stub in his certificate book for keeping his own records was also lost.

A Dr. John T. Connolly was sworn in and testified that he had been called to Dr. Hendrick’s sanatorium to care for Biggar. Dr. Connolly said he saw Laura Biggar deliver a male child 15 minutes after his arrival, and that he attended the mother for one day but saw the child for each day of his brief life. Dr. Connolly admitted that he had made no record in his appointment books about these visits, nor had he recorded any fees being charged; he also testified that he had a prior professional relationship with Dr. Hendrick and the sanitarium.

Dr. Hendrick took the stand next, and over two hours testified that he had been present at the birth of the child and had produced both the birth and death certificates. He also acknowledged that he was serving as Biggar’s lawyer, under power of attorney, with respect to the probate of Bennett’s will. Hendrick said that he had sought out Biggar, whom he claimed to know to be Mrs. Henry Bennett, at the Stock Farm in Farmingdale, and from there, he brought her to his sanatorium.

While the trial was underway, one newspaper reported that Laura Biggar “has been in New York city endeavoring to collect rents from tenants in buildings on Seventy-second street owned by the Bennett estate, but without success, and the courts will likely be called up on to decide he matter.”

Drama in the Courtroom

On Friday, September 26, the Laura Biggar trial exploded.

It began with Charles C. Black, the attorney representing Biggar and her interests in this lawsuit, when he announced “the complete abandonment” of the challenge to the “undue influence” lawsuit.

Lawyers for the Bennett family members and estate executors then brought charges before the judge in the case, asserting “a gigantic conspiracy to steal the millions of the late Henry M. Bennett.” The charges named Biggar, Hendrick, Stanton, and Henry Bennett’s nurse. Hendrick and Stanton, present in the courtroom, were immediately placed under arrest, arraigned, and jailed with bond set at $5,000 each, which would be approximately $170,000 today. Laura Biggar was not present, or she would have been placed under arrest as well. The Bennett estate’s lead attorney said that Charles Black was “innocently duped.” Bennett’s nurse had been fired three weeks after his death and was nowhere to be found.

What happened?

It seems that Samuel Stanton had gotten a little too clever.

Joseph Tucker, a clerk in the Hoboken board of health offices, was a surprise witness this day who testified that, over the weekend following his testimony on Friday, Stanton had asked Tucker for a blank marriage certificate. Stanton left for 15 minutes, then returned with the certificate filled out and signed, and filed it. Then Stanton returned and said, “Joe, I’ve been trapped. I had no right to sign that certificate.” Tucker said Stanton asked that, if asked, Tucker would say that Stanton had been drunk at the time this occurred, but Tucker refused.

Stanton had apparently then made an appearance at the offices of Hoboken lawyers for Bennett’s family and the will’s executors that weekend; they in turn notified Charles C. Black, Biggar’s attorney, and that began the complete unraveling of the conspiracy.

Biggar was now officially a fugitive from justice. In the meantime, lawyers for executors of the Bennett estate declared before the court that they had evidence that the baby used in the conspiracy had been born in Hendrick’s sanatorium, but it was not Biggar’s child, rather, the baby had been birthed by “a poor woman used as a paid confederate of the conspirators.”

Dr. Hendrick was said to have been fully aware of the deception, but gave assurances that Dr. Connolly was “an innocent actor.” Yet Dr. Connolly had testified that he had witnessed Biggar giving birth. Was he deceived into thinking the “poor woman” was Laura Biggar?

For her part, Biggar was facing a possible prison sentence of up to two years, and/or a fine of $500, if convicted, and could lose the bequest that she was originally due under the will, if it survived the “undue influence” challenge.

Bennett estate lawyers also said they had obtained evidence that Anna Weber, the witness whose name was written on the bogus marriage certificate, in fact had never existed, and they also now claimed that the child had not been born at the sanatorium, and that they had witnesses from the sanatorium prepared to testify to this.

The judge that day noted in his remarks that “Miss Biggar appeared in court with a doctor and insisted upon the validity of the will at a time when, according to her later contention, she must have been about to become a mother. It seems strange that a woman in that condition, and being advised by counsel, and knowing that if she gave birth to a child alive, and that if the child died that the will was no will, that she should insist upon having the will probated.” He declared the current proceedings to be over, and that all testimony and evidence would be turned over to a grand jury to determine if criminal charges were warranted, and which would adjudicate the challenges to the will.

Bert Haverly, ex-husband of Biggar, was found by reporters and commented, “She’s moneymad. That’s what she is, moneymad; crazy after money.” Haverly denied ever having married Biggar, and denied having ever sued Bennett for alienation of affections. He later gave lengthy interviews in which he portrayed her in a very negative light.

On September 30, Bennett estate lawyers moved for perjury charges against Stanton to be added to the fraud and conspiracy charges, and his bail was raised to $10,000. A new charge of grand larceny was added to Hendrick’s case; he also remained incarcerated, while Biggar was still at large. Investigators presented additional evidence showing that the Biggar-Bennett marriage and child were both a sham.

Laura Biggar is Finally Heard From

Stanton refused to confess, and Hendrick remained mute. Through her lawyer, a statement from Biggar was read before the court: “I am not guilty of any conspiracy. On the contrary, if there is a conspiracy it is on the other side. But I do not care to surrender myself until I am sure of being able to furnish bail. However, I have no intention of running away. So far, only the other side has been heard, and I am placed in a very bad light, but when my case is presented I expect to turn the tables.”

Biggar’s statement leveled a number of accusations against the lead executor of the Bennett estate, calling him “an employee of Henry M. Bennett – not a confidant, and yet we find him mentioned in the will to the extent of a half a million dollars. He simply hypnotized Mr. Bennett.” She leveled a number of similar insinuations against another opponent.

Biggar’s statement said, “I did not authorize my counsel, Mr. Black, to discontinue the will contest unconditionally. I told him I was ill and not strong enough to wrangle in the courts over it and would withdraw further contest if assured of my 60 percent. It has been made to appear as if I was glad to drop the whole matter. That is not true.”

Biggar repeated her claim to have married Bennett on January 2, and that the certificate given her at the time by Stanton was the same one that was placed in evidence in Long Branch, that it had never left her possession, and that she had no knowledge of nor involvement in the copy that Stanton tried to file with the board of health.

James Willis McConnell Jr., Biggar’s 14-year-old son, told reporters that his mother had visited him during her time staying at the sanatorium, and had told him about her marriage, and the birth and death of the baby.

How the Plan was Hatched

Bennett estate lawyers said that Hendrick and Biggar had cooked up this scheme in a Long Branch hotel room on the night of July 2, 1902, while the hearings were ongoing. That night, 21 absinthe frappes were sent up to the room, ordered by Hendrick. The next morning, Hendrick approached the court with a newly executed power of attorney to represent Biggar. One newspaper reported that at the end of that day’s court session, Hendrick remarked that “We have things cinched so that no matter what happens, Miss Biggar can’t lose.” One wonders why he forgot to call her Mrs. Bennett, as she was supposed to have been married to the millionaire back in January. Hendrick went on to reveal that Biggar was at his sanatarium, “a mental and physical wreck.” The bogus claims of motherhood and matrimony followed shortly thereafter.

It was a plan that was doomed to fail. From the first reports of Biggar being at Hendrick’s sanatorium, lawyers for the opposition said they had witnesses who would contest the marriage and motherhood claims even before they had been brought before the court. Lawyers also found out early on that Hendrick had approached two other justices of the peace in Hoboken, seeking a fake marriage certificate, but they refused. Having first offered $1,000, Hendrick then upped the payment to $1,200, and that was enough to get Stanton to join the conspiracy. Stanton was a man of very little financial means and known debts who suddenly had cash on hand to spend.

In a curious statement, a lawyer for Bennett’s estate said that they had detectives watching everything at the sanatorium, and that “we had a few detectives watching our detectives, and, fortunately so, because we discovered in time to save our case that the other side had brought over one of our men.”

Detectives apparently observed Stanton when he visited the board of health and approached Joe Tucker seeking assistance.

An International Celebrity Offers Bail for Biggar

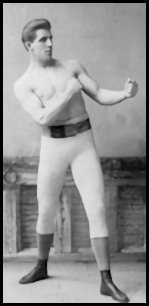

On October 1, 1902, the Asbury Park Press reported that James J. Corbett, former world heavyweight boxing champion and an international celebrity, had offered to pay bail for Laura Biggar. Corbett, nearing the end of his pugilistic career, may have been looking for publicity to draw interest in one of his final fights. He had trained for his first championship bout in Asbury Park, and found the region much to his liking; he met and married his second wife here.

Corbett had arranged for a theater owner in Bayonne to get in touch with Biggar’s lawyer to say that if she surrendered herself immediately, Corbett would pay her $5,000 bail. Biggar did not surrender, and Corbett was not heard from again in this case.

On October 8, 1902, prosecutors made their case to the Monmouth County grand jury that Biggar, Hendrick and Stanton had engaged in conspiracy to commit fraud, and that Hendrick and Stanton had perjured themselves during their testimony. The grand jury was also to determine if Biggar’s claim to motherhood and matrimony were valid, and, if so, then she was entitled to the entire estate.

On October 13, a reporter for the Asbury Park Press succeeded in locating Laura Biggar, who made a lengthy statement that she was not in hiding; that New Jersey officials knew where she was; that she was the victim of a conspiracy, not a conspirator herself; that she was not “money-mad,” and that she did not want anything for herself, but only what was due her, for her son. She stated that Bennett estate lawyers had offered Stanton $10,000 to make a false confession. She described in detail how Bennett had sought her sexual favors while still married, and she had rebuffed him, but after Bennett’s wife died, she agreed to marry him. She said that Bennett had wanted not to go public with the marriage as his wife had only been deceased a short time, and it would cause a scandal.

After a number of breathless reports that Biggar would surrender, finally, on November 4, she and attorney Frankenstein walked into the sheriff’s office and gave herself up, saying that as long as Hendrick and Stanton were incarcerated, she should be as well. Biggar said that she had been staying the entire time in an apartment Bennett had willed her on East 33rd Street in New York City, and that she had made no effort to conceal herself. Laura Biggar spent one night in jail and then was released on $5,000 bail.

While the Monmouth County grand jury considered the Biggar case, Laura Biggar announced that she planned to return to the stage, appearing in a 20-minute sketch called A Strange Baby, set to open in Pittsburgh, where she would earn $1,000 per week. Newspapers also reported that Biggar had obtained copies from several hotel check-in registers showing that Bennett and Biggar had stayed there as “H.M. Bennett and wife.”

On November 14, the grand jury handed down indictments against Biggar, Hendrick, and Stanton for conspiracy, and one count of perjury for Stanton.

The grand jury indictment included the following:

That…persons of evil minds and dispositions, together with divers other evil disposed persons…knowingly, wickedly, and unlawfully devising and intending to nullify and make void the last will and testament of the late Henry M. Bennett.

Biggar returned to the stage in Pittsburgh, billing herself now as Mrs. Laura Biggar Bennett. The judge in the case agreed to a request from defense counsel to postpone the trial until December.

The Trial of Laura Biggar

On December 17, 1903, the trial of Laura Biggar, C.C. Hendrick and Samuel Stanton began. Biggar, on advice of counsel, refused to plead to charges against Laura Biggar, saying she would only plead as “Laura A. Bennett.” Prosecutors refused, the judge agreed, but Biggar would not relent, and so as per standard court procedure, a plea of “not guilty” was entered for her by the court.

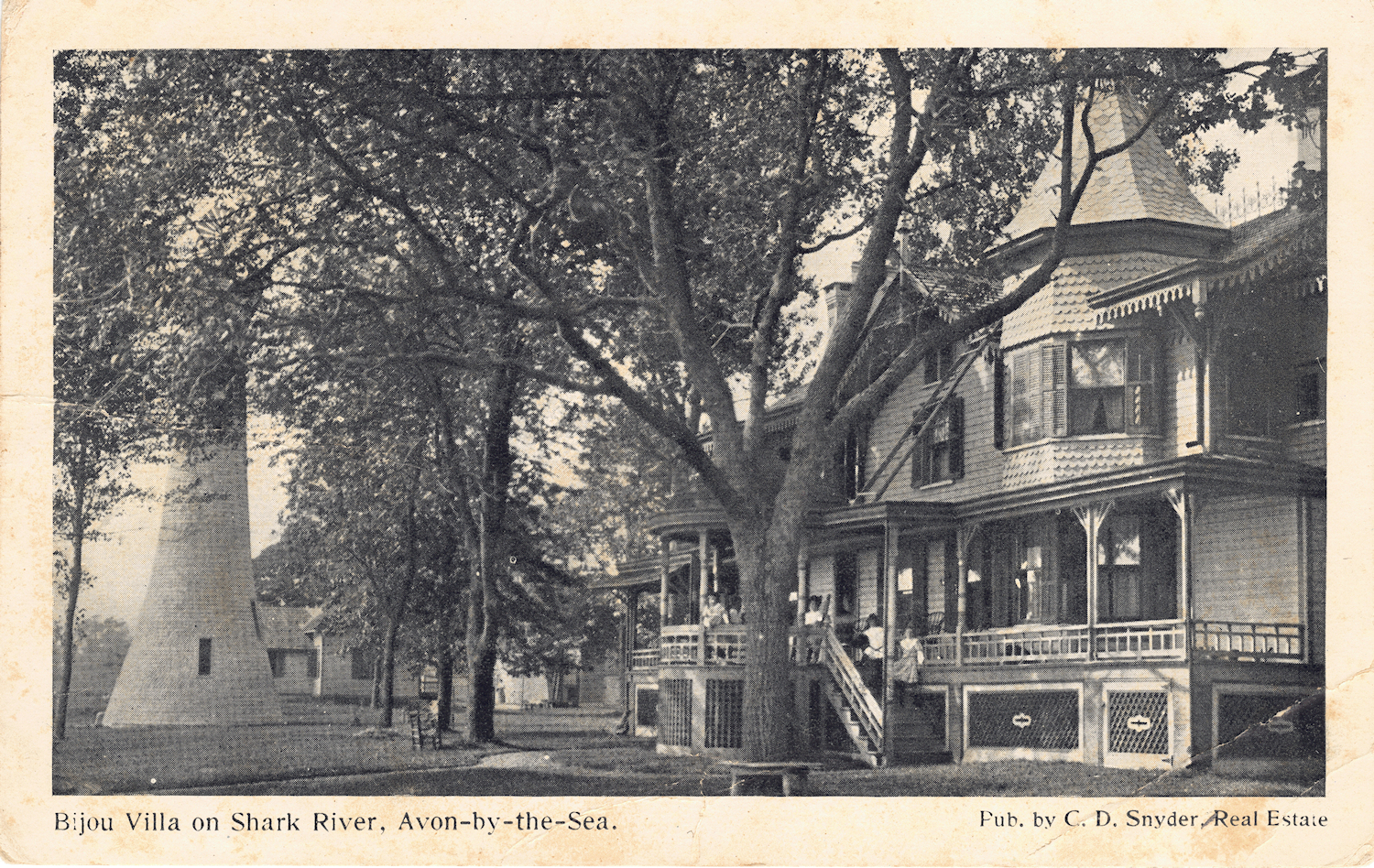

Prosecutors needed only one day to lay out their case, focusing on evidence such as the wedding certificate from 1898, saying it had been made out on a certificate pad that was printed in 1900, and hence, was fraudulent. Joseph Tucker repeated his story. A surprise witness for the defense was James W. McConnell, Biggar’s first husband. McConnell stated that he had been invited to Henry Bennett’s home in Avon-by-the-Sea, called “Bijou Villa,” on the north bank of Shark River, where Bennett, noting that he and Biggar were now married, could afford to take much better care of McConnell and Biggar’s son. McConnell agreed, and the son was left in the care of mother and putative stepfather. McConnell also testified that his ex-wife had continued using her maiden name after their marriage. Other witnesses were called who testified that Bennett had referred to Biggar as his wife on numerous occasions. Dr. Connolly took the stand and repeated that he had witnessed Laura Biggar giving birth to an infant son who died two weeks later.

In response to prosecutors who introduced letters Biggar had signed as “Laura Biggar” after her January 2 wedding to Bennett, defense attorneys argued that it was common practice in the entertainment industry for stars such as Laura Biggar to continue using the same stage name in their work even after marriage.

On December 19, Hendrick and Stanton each testified about their roles in the alleged conspiracy. Stanton claimed to be unable to remember many of the details sought by prosecutors, saying he was drunk at the time. He repeated that he had presided over a wedding ceremony of Bennett and Biggar.

Finally, Laura Biggar swore an oath and took the witness stand. She was “becomingly attired,” said to have “recovered her equanimity” and “evinced a degree of firmness that…was somewhat surprising.”

A Startling Verdict

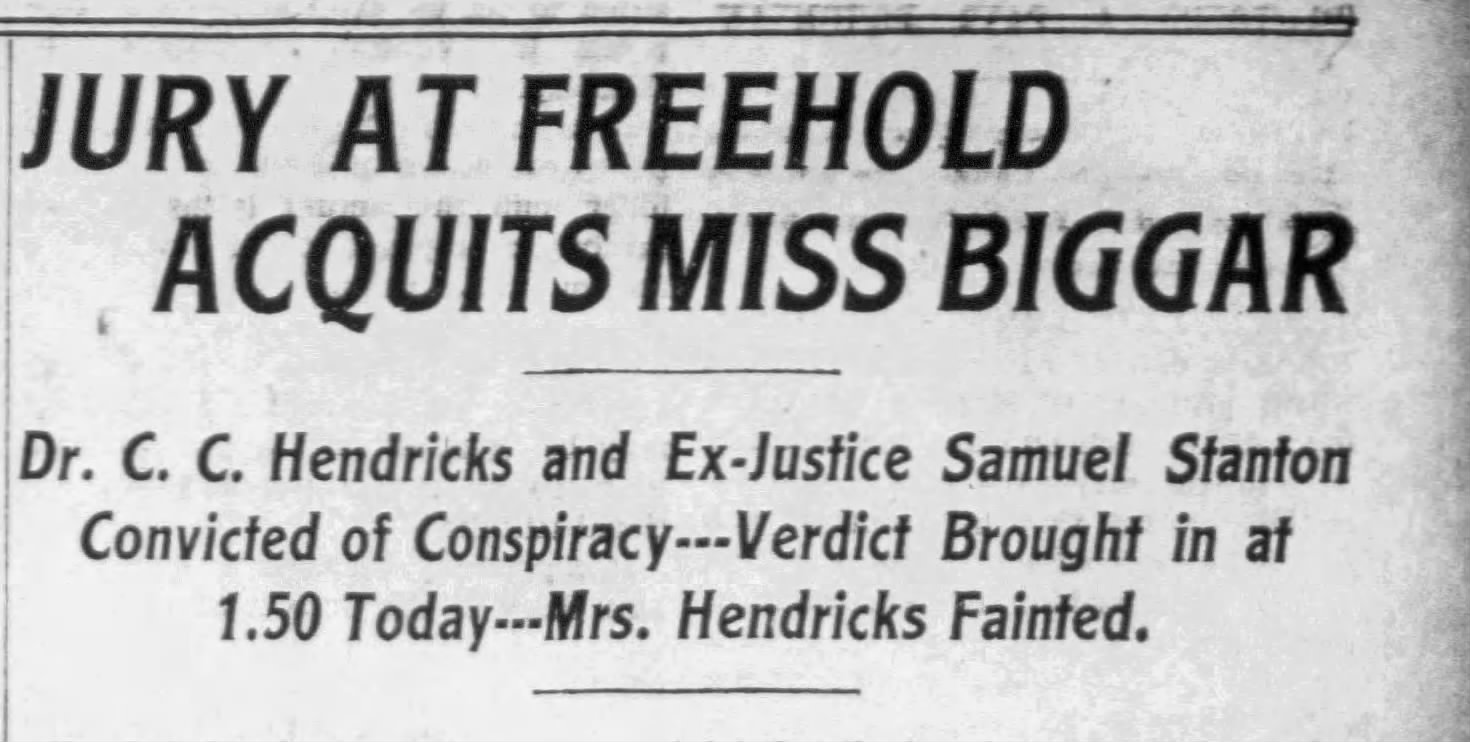

On December 24, Christmas Eve, 1902, Laura Biggar received gift of freedom and redemption when she was found to be not guilty by the Monmouth County jury. C.C. Hendrick and Samuel Stanton were both found guilty, Hendrick of conspiracy, Stanton of conspiracy and perjury.

Jurors said they were unanimous in seeing the clear culpability of Hendrick and Stanton, but that there was sympathy for Biggar, a likeable sort, and that jurors were even at 6-6 for conviction at first, then voted 11-1 to acquit, and then finally 12-0. Biggar spent Christmas in Freehold, having her dinner at the jail, saying she had no money and no place to go.

Observers were quick to find fault with the jury’s decisions. An editorial in the Asbury Park Press noted:

Everywhere the verdict of the jury in the Laura Biggar conspiracy case…is laughed at as a travesty on justice…How could there be a marriage conspiracy without a woman? The jury that could acquit Laura Biggar and convict Hendrick and Stanton ought to be kept together as a traveling show. Hendrick and Stanton should be let go. If Laura Biggar is not guilty then Hendrick and Stanton are equally innocent.

On another occasion, the Park Press opined, “On what grounds such a verdict was rendered no sane man has been able to discover.”

On December 27, Laura Biggar returned to New York City, telling reporters that she preferred now to be called “Mrs. Bennett,” and that she would focus her energy on freeing Hendrick and Stanton on appeal. She then renewed her career, but not without drawing the ire of some. Local clergy in Bridgeport, Conn., protested her stage appearance of A Strange Baby on moral grounds, saying that it would “degrade the morals of the community.”

On January 15, the judge in the Biggar case sentenced Hendrick and Stanton each to two years and six months in state prison.

The Doctor/Lawyer Becomes an Actor and Co-Star, and Biggar Returns to Monmouth County

On February 3, 1903, the Asbury Park Press reported that Dr. C.C. Hendrick, convicted of conspiracy but out on bail pending appeal, would become the co-star of Laura Biggar in a new production of the vaudeville stage production, A Strange Baby. It was not immediately known what sort of part or role Hendrick would perform.

Four days later, Hendrick returned to Freehold “to make arrangements for the appearance of Laura Biggar in a benefit for the Freehold fire department to be given soon.” The doctor was also said to be tending to affairs relating to his appeal, assisted by Laura Biggar.

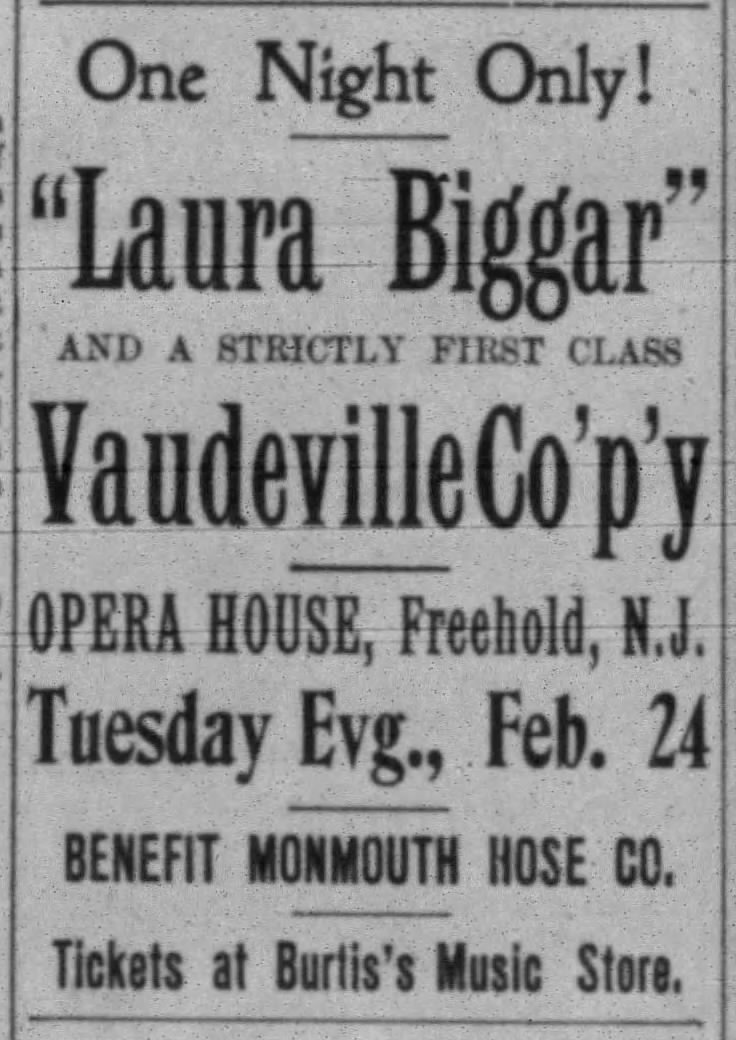

On February 12, the manager of the Asbury Park Opera House announced that he had arranged for a performance on February 16 by Laura Biggar, Dr. C.C. Hendrick, “and a chaste, polite vaudeville company direct from Proctor’s theatre, New York.” Shortly thereafter, Biggar and Hendrick were booked to play the Freehold Opera House on February 24. The Asbury Park performance was well-attended and well-received, and the Freehold performance was likewise praised:

The Laura Biggar Vaudeville Company gave an excellent entertainment in the Opera House on Tuesday evening. The Monmouth Hose company netted about $100.

Meanwhile, Stanton – remember Samuel Stanton, the other convicted co-conspirator? – he remained in the county jail, still unable to secure bail. He was stuck there for another month.

But, true to her word, Laura Biggar and C.C. Hendrick had not stopped in their efforts to get Stanton freed, and they ultimately managed to round up enough to satisfy a bail bondsman, and Stanton finally was able to walk out while his case remained pending under appeal on March 25.

Hendrick was not having as much luck in his efforts to break into the entertainment industry:

Dr. Hendrick’s engagement at the Bon Ton Theatre, in Jersey City, came to an abrupt termination Saturday, when he did not appear at the matinee performance. The former Hudson County health inspector has had far from a good week. He was to have received all over and above $1600 taken in at the theatre, but he failed to prove the drawing card expected and there was nothing left for him and his company.

While out on bail, Stanton repeated his claim that an attorney representing Bennett’s estate executors had offered him $10,000 and passage to Europe if he would make a false affidavit.

A Scorned Wife Extracts Her Restitution

Meanwhile, Mrs. Agnes M. Hendrick – Charles having been married with children this entire time – finally had enough and sued C.C. Hendrick for abandonment in court in Coney Island, saying, “He would rather follow that woman and see her act than remain at home with his wife and children.” Hendrick was ordered to pay his wife $100 per month.

While performing in a production of East Lynn at the Taylor Opera House in Trenton, Biggar took ill and was unable to continue after the first act. But as the Asbury Park Press put it, “Empty Seats Didn’t Mourn When Laura Biggar Was Replaced.” The audience was apparently fairly small and a poor performance by the understudy made this vaudeville company “the poorest seen at the Trenton Opera House this season, it is said.” Biggar performed once more, in her home town of Wilmington, Delaware, and then announced she was retiring from the stage once more.

On May 28, the regular list of Monmouth County real estate transfers included two from Laura Biggar Bennett to the two Pittsburgh men, one being Bennett’s Neptune residence, and the other the Windsor Stock Farm, each for one dollar, as part of liquidating her inheritance.

On June 11, Mrs. Agnes M. Hendrick announced that she had brought a lawsuit against “Miss Laura Biggar” for alienation of affections relating to her husband, seeking $100,000 in damages. Two weeks later, Hendrick filed for divorce, claiming that she was unfaithful. On August 19, Agnes went public, telling her side of the story in lurid detail, and declaring her husband of being “intimate” with Laura Biggar. Mrs. Hendrick named a man and denied accusations that she had had an affair with him. She named several places and dates where she claimed Hendrick and Biggar carried on their own affair. Despite all this drama, in the end, the judge found in favor of Agnes in the amount of ten dollars per month separate maintenance.

On Monday, November 8, 1903, the New Jersey supreme court ordered a new trial for both Hendrick and Stanton. The basis for overturning the convictions stemmed from Laura Biggar’s testimony during their initial trials, in which evidence was introduced from her own trial, in which she was acquitted. The court decided that this was therefore improper evidence introduced by the prosecution. The court’s decision said in part:

She was a witness for the plaintiffs, in error, and the tendency of the evidence was, if believed, to reveal in her a condition of extreme moral degradation. We can see where the effect of exposure might be to discredit her testimony with the jury.

On December 30, 1903, a breathless story told of a brazen street kidnapping in which C.C. Hendrick picked up his son Thomas and took him away in a speeding horse-drawn coach. The boy cried out for help and onlookers stopped the cab and demanded to know what was going on and the man told them, “I’m his father…and I guess I know what I’m doing.”

Later, reports appeared suggesting that Biggar and Hendrick had taken the child to Vermont, en route to Canada. But the boy turned up in Boston in March, and Mrs. Hendrick immediately went before a supreme court judge to make a claim for custody, which was ultimately granted.

On December 13, 1904, a judge decreed that Laura Biggar would have to wait for five years to be able to take possession of her bequeathal from Henry M. Bennett. Saying that she was denied the opportunity to present her case, she appealed to the supreme court to have the judge in the case replaced.

And yet, just a day later, it was announced that the Bennett estate was finally settled. In light of the convictions for Stanton and Hendrick being overturned, and no indication that there was any intention to bring them to trial again, lawyers for the estate reached a settlement in which “Mrs. Bennett” would receive securities in the amount of $240,000, paid in monthly installments, and another $40,ooo in cash.

Biggar’s next challenge was suing to recover or reduce some of the exorbitant legal fees she had incurred during this time, claiming she was coerced into signing contracts for payments. These complex legal wranglings went on for some time, but at the same time, Charles Hendrick, acting as Biggar’s lawyer, was now initiating procedures to have the executors of Bennett’s estate removed, but this ultimately failed.

In 1905, Agnes Hendrick finally succeeded in winning a divorce from her husband, and she moved forward with her lawsuit for $100,000 in damages from Laura Biggar.

On July 18, 1906, it was announced that Biggar had finally reached a settlement with the Pittsburgh heirs for Bennett’s real estate holdings, with the actress to receive approximately $500,000 for her share.

Laura Biggar: Actress-Heiress-Newspaper Editor?

In April of 1908, The New York Times reported that “Laura Biggar Bennett” had become the new editor of the Daily Sun newspaper in Albuquerque, New Mexico. She had fallen in love with the climate of the region, and purchased the newspaper from the proceedings of her inheritance. Charles C. Hendrick, doctor-lawyer-actor, now added newspaper editor to his career as well. In less than one year, the newspaper folded from “small patronage.”

In 1909, Biggar announced that she would once again return to the stage. But what she was mostly doing throughout this period of her life was making appearances in various courtrooms, as the various legal complexities of all of her transactions generated a seemingly endless stream of lawsuits of various types.

On July 5, 1909, The New York Times reported that Biggar had received her payment for her share of the Pittsburgh Bijou Theatre, just under $160,000, in gold coins, over 700 pounds worth, said to have required six porters and clerks to transport it aboard a train in Asbury Park, where she had negotiated the sale with the theater’s other owners. Later, bank officials denied the story. As part of completing that transaction, it meant an end to one of the lawsuits against her. But not all verdicts were going her way.

On February 11, 1910, Agnes M. Hendrick prevailed in her lawsuit against Laura Biggar for alienation of affection, and Biggar was ordered to pay $75,000 in damages, which on appeal was reduced to $50,000. The lurid details that came out in court made national news. In October of 1911, Laura Biggar asked the court to set aside the judgment and reopen the case, citing new evidence. That request was denied, but upon appeal, the sum for damages was further reduced to $30,000. Hendrick had never paid his wife a single penny.

Meanwhile, Biggar was still wrangling with various interests in Pittsburgh, filing her 19th lawsuit there in 1911, in her attempts to complete a settlement of Bennett’s real estate holdings there.

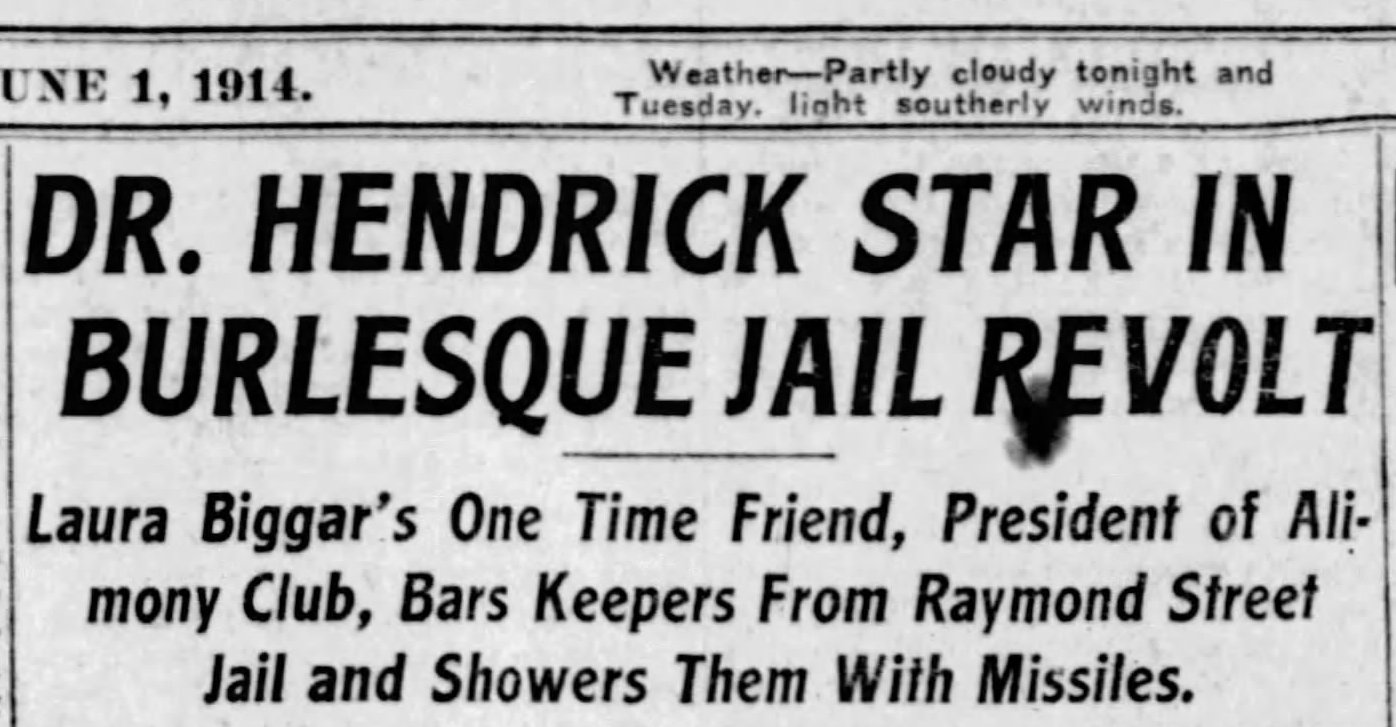

In December of 1913, Hendrick was arrested and thrown in jail for failure to make required payments to his wife. In a Brooklyn jail filled with other men there for the same reason (newspapers called it “the alimony club”), Hendrick apparently led a prison riot. On a hot steamy night in June, jail wardens went outside to cool off, and when they went to return, found themselves locked out. Inmates from the second-floor dining room began hurling pots, pans, plates, silverware and other missiles at the hapless guards. Eventually, order was restored, and Hendrick, considered the organizer of the revolt, was placed in solitary confinement on a diet of bread and water. He was eventually released on a writ of habeas corpus, after having served a six-month sentence.

In August of 1914, the Los Angeles County Sheriff announced the sale of the Biggar/Hendrick property on Bretherton Place to Agnes M. Hendrick as she continued pursuing her judgment payments.

On May 11, 1916, C.C. Hendrick and Laura “Biggar-Bennett” were married in Plainfield, N.J. They moved into the Dunellen home formerly of boxing champion Robert “Ruby Bob” Fitzsimmons. Coincidentally, Fitzsimmons was the pugilist who in 1897 had dethroned world heavyweight champion James J. “Gentleman Jim” Corbett, who had at one time offered to post bail for Laura Biggar.

Their ownership of that property became the subject of yet another round of contentious and complex litigation at the behest of Agnes. J.W. McConnell Jr., Biggar’s son, paid Agnes a settlement of $15,000 which finally “wiped out” the alienation of affection judgment. The couple said they planned to establish a sanitarium for invalids. “Mrs. Hendrick is also a practitioner of chiropractic, having taken it up after her own experience with the treatment which she credits with having saved her life.”

Charles C. Hendrick died suddenly of a heart attack on June 26, 1918 in Dunellen, age 55. After his death, his brother tried to claim the Fitzsimmons estate, saying that Dr. Hendrick had no children, but of course, he had three, and the once-kidnapped son Thomas showed up and the entire matter became yet another a criminal investigation in which Laura was compelled to testify.

After 1918 Laura Biggar finally dropped out of the spotlight and lived the rest of her life quietly, at 3527 West Adams Street in the wealthy Jefferson Park section of Los Angeles with her son and his wife. She died on January 5, 1935, of heart disease, age 69. It is not known where either she or Dr. Hendrick are buried. After his release, nothing was heard from Samuel C. Stanton again.

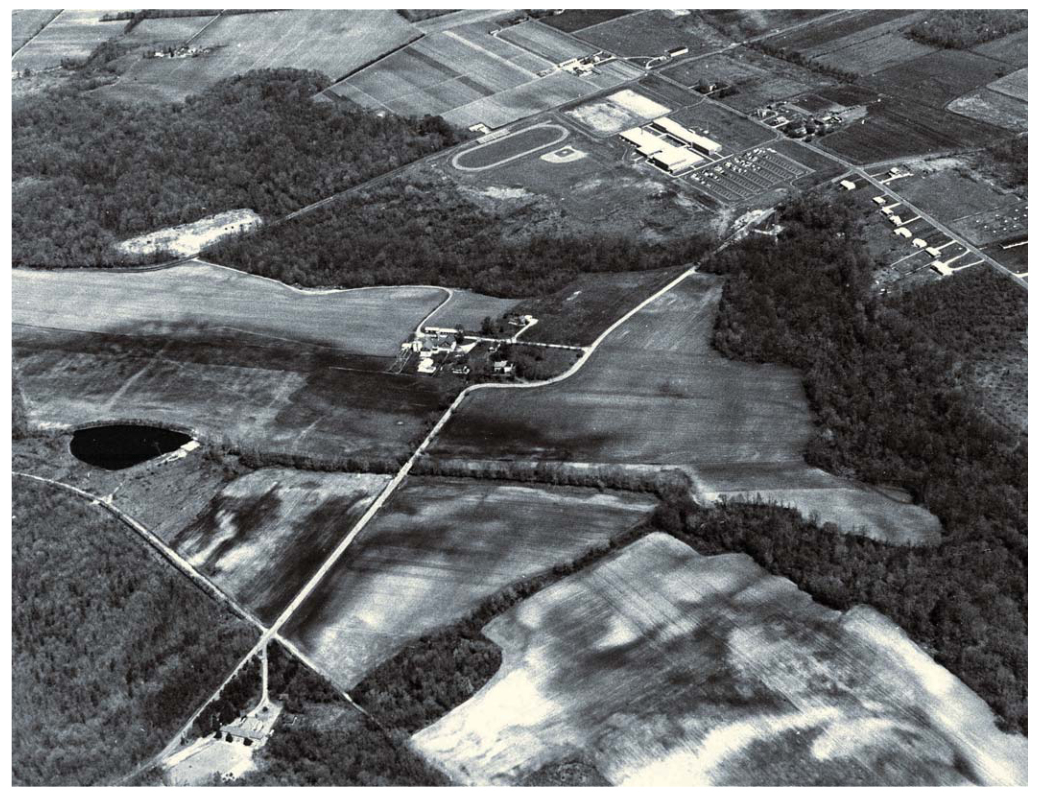

In 1967, the Monmouth County Freeholders voted to purchase the Windsor Stock Farm property in Farmingdale, so as to construct and offer to the public the Howell Park Golf Course that is in operation there today as a part of the Monmouth County Parks System.

WAS Laura Biggar a “gold-digger?”

Her second husband, Bert Haverly, certainly thought so, and said so in as many words. But what’s most revealing is in newspaper accounts of trial testimony, affidavits, and written accounts by the principals for the court, is that Laura Biggar never said she loved Henry M. Bennett. She seemed to imply that he was so smitten with her, and wanted to marry her, and she more or less went along with it, but not out of love, at least, according to the statement she made. She said she wanted to gain that which he wanted her to have, for her son. Newspapers were more polite in that era, so the phrase “gold-digger” was never used, but it has been consistently when young starlets marry elderly millionaires. In this case, who can know what’s truly in a person’s heart?

Sources:

$500,000 for Laura Biggar. (1906). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., July 18, 1906, P. 1.

Actress Eluded Deputy Sheriff. (1901). The Star Press, Muncie, Ind., April 20, 1901, P. 1.

Actress Now Claims the Entire Estate. (1902). Long Branch Record, Long Branch, N.J., September 12, 1902, P. 1.

Bennett Case Settled. (1904). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., December 14, P. 12.

Big Legacy for Actress (1902). Almost Entire Estate of Millionaire Henry M. Bennett of Asbury Park Left to Laura Biggar. The New York Times, New York, N.Y., April 15, 1902, Page 7.

Biggar Lawsuit Will Be Famous. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., September 20, 1902, P. 1.

Biggar Lawsuit will be Famous. (1902). The Monmouth Inquirer, Freehold, N.J., September 25, 1902, P. 1.

Condensed Dispatches. (1903). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., June 11,1903, P. 2.

CPI Inflation Calculator. (2013). Available: https://www.in2013dollars.com/.

Dr. Hendrick Star in Burlesque Jail Revolt. (1914). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., June 1, 1914, P. 1.

Dr. Hendrick’s Wife’s Troubles. (1903). The Freehold Transcript, Freehold, N.J., April 17, 1903, P. 3.

Evidence Favors Wifehood Claim. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., September 19, 1902, P. 1.

Freehold. (1903). The Monmouth Inquirer, Freehold, N.J., February 26, 1903, P. 1.

The Grand Jury at Work. (1902). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., October 8, 1902, P. 1.

Great Conspiracy to Steal Millions. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., September 26, 1902, P. 1.

H.M. Bennett’s Will is Read to Heirs. (1902). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., April 15, 1902, P. 1.

Heart Failure Kills Hendrick. (1918). The Brooklyn Daily Times, Brooklyn, N.Y., June 27, 1918, P. 2.

Heisley Sentences Biggar Conspirators. (1903). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., January 15, 1903, P. 1.

Hendrick Steals Child from Wife. (1903). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 30, 1903, P. 1.

Hendrick’s Wife Denies Charge. (1903). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., August 19, 1903, P. 1.

Hendrick Will Also Go on Stage. (1903). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., Feb 3, 1903, P. 1.

Henry M. Bennett Died Yesterday. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., April 12, 1902, P. 1.

In Monmouth County. (1903). The Daily Standard, Red Bank, N.J., February 7, 1903, P. 10.

Indictments in Biggar Case. (1902). The Freehold Transcript, Freehold, N.J., November 14, 1902, P. 1.

Interview on a Noted Case. (1916). The Courier News, Plainfield, N.J., May 22, 1916, P. 3.

Jury at Freehold Acquits Miss Biggar. (1902). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 24, 1902, P. 1.

Lindenmuth, Janet. (2017). Biggar Than Life: The Forgotten Story of How a Girl from Delaware Gained Wealth and Fame Through the Power of Charm, Talent, and Lawyers. Widener Law Library Blog, January 23rd, 2017. Available: ttps://blogs.lawlib.widener.edu/.

Laura Biggar at Sanitarium. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., June 23, 1902, P. 1.

Laura Biggar Claims She is Legal Widow. (1902). Asbury Park Press, August 18, 1902, P. 1.

Laura Biggar Coming. (1903). The Shore Press, Asbury Park, N.J., February 12, 1903, P. 2.

Laura Biggar is in Freehold Jail. (1902). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., November 4, 1902, P. 1.

Laura Biggar Must Wait. Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 13, 1904, P. 1.

Laura Biggar Now Editor. (1908). The New York Times, New York, N.Y., April 26, 1908, P. 1.

Laura Biggar Says She Married Bennett. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 19, 1902, P. 1.

Laura Biggar Stirs Clergy. (1903). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., January 5, 1903, P. 1.

Laura Biggar’s Fight for Bennett’s Wealth. (1902). Long Branch Record, Long Branch, N.J., September 19, 1902, P. 1.

Mattered Little to House. (1903). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., May 6, 1903, P. 2.

Miss Biggar is Still At Large. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., September 30, 1902, P. 1.

Miss Biggar May Surrender Today. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., September 27, 1902, P. 1.

Must Pay Wife $75,000. (1910). The Morning Call, Allentown, Pa., Feb 12, 1910, P. 1.

A New Trial Ordered. (1903). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., November 11, 1903, P. 12.

Prominent Actors in Biggar Conspiracy. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., September 29, 1902, P. 2.

Real Estate Transfers. (1903). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., May 28, 1903, P. 3.

Retired Actress is Heart Disease Victim. (1935). Stockton Independent, Stockton, Calif., January 5, 1935, P. 12.

Rite Near for Laura Biggar, Stage Figure. (1935). Los Angeles Evening Citizen News, Los Angeles, Calif., January 5, 1935, P. 6.

Sacks of Theater Money. (1909). The New York Times, New York, N.Y., July 5, 1909, P. 7.

Stanton Released. (1903). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., March 25, P. 1.

A Strange Baby. (1902). Long Branch Record, Long Branch, N.J., November 14, 1902, P. 13.

Take License Out to Wed. (1916). The Boston Globe, Boston, Mass., May 20, 1916, P. 10.

Theatrical. (1897). The Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., May 25, 1897, P. 8.

A Travesty on Justice. (1902). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 26, 1902, P. 4.

Trying Biggar Case. (1902). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., December 18, 1902, P. 1.

Victim of a Plot, Says Miss Biggar. (1902). Asbury Park Daily Press, Asbury Park, N.J., October 13, 1902, P. 1.

Were Laura Biggar and Bennett Wedded? (1902). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., August 16, 1902, P. 2.

Will Free Her Friends. (1902). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 27, 1902, P. 1.

Leave a Reply