By John R. Barrows

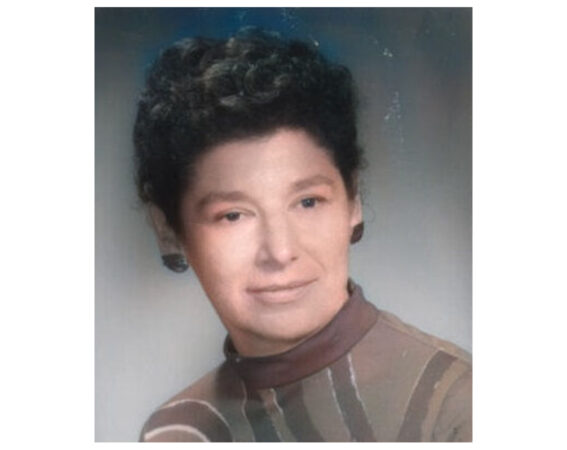

On November 14, 1973, the U.S. Army Electronics Command (ECOM) presented the Army Research and Development Achievement Award to three civilian Fort Monmouth employees: Dr. Pete H. Hudson Jr., of Freehold; Louis J. Jasper Jr., from Neptune, and Marilyn Levy, a photo-optics chemist then living in Red Bank. The most prestigious honor the Army gives to in-house laboratory personnel for outstanding technical achievement, the awards were presented at Fort Monmouth by Lt. Gen. John R. Deane Jr., Chief of Army Research and Development.

This award came just two years after Marilyn Levy was awarded the Army’s second highest award for civilian employees, the Meritorious Civilian Service Award, one of only four women at Fort Monmouth to be so honored.

For most of her career, Marilyn Levy was a chemist in the Photo-Optics Technical Area, Electronics Command Surveillance and Target Acquisition Laboratory at The Hexagon at Fort Monmouth. Her work involved research in high-speed photographic processing, both black and white and color; dry photographic techniques; and photography for aerial surveillance. Over her lifetime she was awarded 35 patents, primarily in areas involving light-sensitive materials, photographic chemistry, and image microstructure.

The Importance of Photography in Military Affairs

The first photographs of battle were taken using the Daguerreotype system during America’s war with Mexico in 1846-7. Similar systems were used to take early battlefield images of the Crimean War as well as the American Civil War. But cameras were not used by the military until World War I. The advent of aviation meant that photographs of enemy positions could be taken from airplanes or airships, providing critical intelligence about troop movements, defensive assets, the results of artillery bombardment, etc.

During the Vietnam War, which coincided with Levy’s career, enlisted soldiers were part of the Department of the Army’s Special Photographic Office (DASPO) — authorized by President John F. Kennedy in 1962 — which sent members to the war with cameras. Over 200 of the soldier-photographers were sent out over the course of a decade, and two of them were killed in action.

During Marilyn Levy’s career, digital photography was still in its infancy, and so during her time working at Fort Monmouth the Army still had to rely largely on single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras that used film, typically 35mm, which had to be developed in a darkroom, a somewhat laborious process. Mistakes in exposure by an Army photographer, working close to the front lines, often under enemy fire, often meant ruined images.

In the heat of battle, success often depended on how fast any given military command could receive reconnaissance photos of usable quality. Marilyn Levy’s entire career was devoted to this, to helping the Army get high-quality images from their photographers regardless of exposure, and accelerating the process of developing and printing as much as possible.

A Modest Genius from Forest Hills

She was born on a date unknown in 1922 to parents Moses and Rachel Levy of Forest Hills; she had a brother, Norman Lee (not Levy), who was a mechanical engineer also working at the Hex. Levy graduated from Hunter College in 1942with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and pursued graduate studies at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. Before going to work for the government in 1951 as a chemical inspector, she was a chemist for various firms in New York.

She was first employed at Fort Monmouth in 1953, and lived in a home at 100 McLaren Street in Red Bank, just outside the historic district, where she resided for 20 years. She never married or had children, but she was active in the Foster Parents Plan, sending financial support to needy children in foreign countries. Throughout her life, she was active in the Monmouth chapter of the Society of Photographic Scientists and Engineers (SPSE).

In 1958, Levy was among ten civilian employees at Fort Monmouth who were the first group to receive the Army’s new $150 cash (about $1500 today) incentive awards for invention patents. She was the only woman to receive this award.

In 1962 she was honored by the SPSE with their Service Sward for her work on “rapid photographic processes and related fields. By age forty she had already earned nine patents.

In 1963, Levy presented a paper at the annual conference of the Monmouth chapter of SPSE in Atlantic City, entitled “Applications of Photographic Emulsion Modulation-Transfer Curves.”

One of her most noteworthy breakthroughs was creating a “Heat Erasable Photosensitive Coating and Process of Using Same.” This now enabled a transparency, whether positive (like a color slide) or negative, to be reproduced “merely by exposure to suitable light. The picture remains on the sensitive material long enough to be scanned electronically or copied by a conventional photographic process. When it has served its purpose, the picture can be erased by the application of heat.” The benefit was enabling the copying of an image from a transparency in ordinary room light, not a darkroom. For the Army, this meant faster recon intelligence that no longer required special facilities.

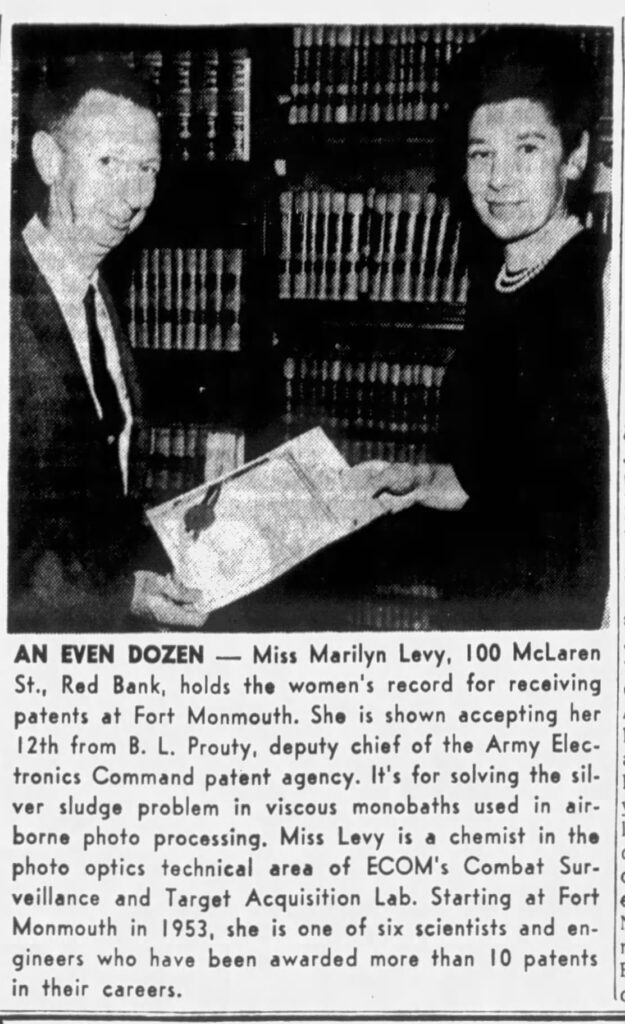

In 1965, Levy received her 12th patent, setting a new record for women-held patents at Fort Monmouth. She was one of six scientists and engineers who were awarded more than ten patents in their careers at Fort Monmouth. By 1966 she was working in the ECOM Combat Surveillance, Night Vision and Target Acquisition Laboratories.

ECOM recognized Levy’s efforts in 1968 with a Special Act Award for her breakthrough in “wide latitude photography.” Wide latitude photography involved chemical formulae that greatly extended the exposure range for color images, enabling excellent quality pictures even when film had received 100,000 times the correct exposure. Her work was used in in private sector applications by Xerox, Bell Telephone, and the Kitt Peak National Observatory.

She was awarded the Meritorious Service Award in 1971 for her work in significantly improving the speed at which photographs could be developed and/or printed. One of her patents was for a combined developer and fixer that enabled film processing in one solution rather than the normal four separate solutions required. By 1971, Marilyn Levy had authored 15 technical articles.

A Move to Little Silver

In 1974, Marilyn Levy moved into a new three-bedroom home at 56 Cheshire Square in Little Silver, where she resided for 40 years, the remainder of her life. The Cheshire Square development sits on the land that was once the home of John Thompson Lovett’s internationally-acclaimed nursery.

Levy served as chairman of the processing section of the SPSE, served on the editorial review board of technical publications Photographic Science and Engineering and the Journal of Applied Photographic Engineering. She was also a member of the American National Standards Institute’s standardization committee on photographic sensitometry.

In 1975, she discovered a new color film process for Kodak Ektacolor-S and Kodacolor-X film that reduced film development processing time from 53 minutes to 11, and a printing process that eliminated “many tedious hours” of darkroom work. Levy’s new process reduced the number of required sequential steps necessary to develop color film from ten to four.

“I began my research about two years ago to produce a more rapid processing system in conjunction with the U.S. Army aerial surveillance operations,” said Levy. “And the public will benefit because it was supported by public funds. The reduced time consumed in processing will be a great help to the army and the general public.” Lt. Harmon A. Willey of Long Branch and Lt. Richard G. LeSchander of Trenton worked with Levy on this breakthrough.

As a result of her consistently strong work, Marilyn Levy was promoted in 1975 to civil service grade GS-15, the highest civil service grade, and which provides for the maximum financial compensation an Army civilian employee can earn. At that time, she was the only woman in the Army ECOM holding that grade.

In May of 1979 Levy received two patents, one for a new method of color film processing that reduced possible false color reproduction, a patent shared with Milan Schwartz. The other was an aerial photo-reconnaissance/surveillance system in which the landscape to be scanned was photographed on color film. The film was then developed in a high-speed processor and then scanned by photosensors. Electronic circuits compared the transmission of different colors of light through the film to identify a target by its “color signature.” This patent was shared with Vincent W. Ball. By now Levy was “chief” of the Photo Optics Division and had been at Fort Monmouth for more than 25 years. These two patents were Nos. 19 and 20 for Levy. By the time she retired, she had earned 35 patents in total, many of which after 1979 were extensions of existing patents into new countries.

In October of 1979, Levy retired. She was active in the Little Silver community, and she was passionate about art, travel, music, gardening, and languages. “She was by nature an experimentalist and took up a succession of artistic pursuits, largely by teaching herself and trying different forms and techniques. She became a skilled water colorist, silver jewelry maker, and innovative potter.” A lifelong swimmer, she was a regular at the Red Bank YMCA pool.

She died June 19, 2014, at age 92, after living in Little Silver for more than 40 years. She is buried in a family plot at Riverside Cemetery in Saddle Brook, Bergen County, N.J.

Legacy

Marilyn Levy was beginning her series of amazing patented inventions in the area of military photography at the time of the onset of the Vietnam War. Digital photography was still many years away, and so all reconnaissance intelligence gathering still involved the use of single-lens reflex cameras (SLR), and film that had to be developed and printed using a darkroom and a series of time-consuming steps. By the end of the war Marilyn Levy had eliminated the need for a darkroom, reduced the number of solutions from four to one, lowered the number of discreet steps in the development process from ten to four, and reduced development processing time from 53 minutes to 11. Her work ensured that even if a photographer significantly over-exposed his film, high-quality images were still a result.

If lives depended on military command getting high-quality images from Army photographers in minimal time, then Marilyn Levy’s legacy can be measured in those who may have become casualties in an earlier era of darkrooms and slow processing.

Sources:

Photo Chapter Elects Officers. (1958). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., June 26, 1958, P. 17.

Army Awards 10 Inventors. (1958). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., December 4, 1958, P. 46.

Destitute Foreign Youngsters Get Aid from Shore Residents. (1961). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., May 8, 1961, P. 13.

Pupils Offer to Help at Country Fair. (1962). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., June 15, 1962, P. 7.

Photographic Scientists to Convene. (1963). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., April 1, 1963, P. 2.

Photo Coating Patent Goes to Fort Chemist. (1965). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., March 23, 1965, P. 16.

An Even Dozen. (1965). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., September 9, 1965, P. 11.

Army Awards Miss Levy Meritorious Civilian Medal. (1971). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., June 13, 1971, P. D14.

High Honor Goes to Miss Levy. (1971). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., June 29, 1971, P. 8.

Army Research and Development Newsmagazine. (1972). Headquarters, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., January-February 1972, Vol. 13, No. 1.

Beardsley, Frank. (1972). Woman Speeds Color Print Processing. Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., June 18, 1972, P. C12.

Three ECOM Employees Get Army Achievement Awards. (1973). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., November 13, 1973, P. 12.

Three Honored by Army. (1973). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., November 14, 1973, P. 7.

Chemist earns GS-15. (1975). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., June 25, 1975, P. D 11.

Retired Scientist is Honored. (1979). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., September 27, 1979, P. 23.

Fort Employees Get 2 Patents for Photography Development. (1979). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., May 20, P. 43.

Local Happenings. (1979). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., October 7, 1979, P. E12.

Marilyn Levy. Age: 92. Little Silver. (2014). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., June 29, 2014, P. A15.

Marilyn Levy. (2014). Findagrave.com. Available: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/236744495/marilyn-levy

Zhang, Michael. (2016). The Soldiers Who Photographed the Vietnam War. PetaPixel.com, March 23, 2016. Available: https://petapixel.com/2016/03/23/soldiers-photographed-vietnam-war/

Excellent article!!!