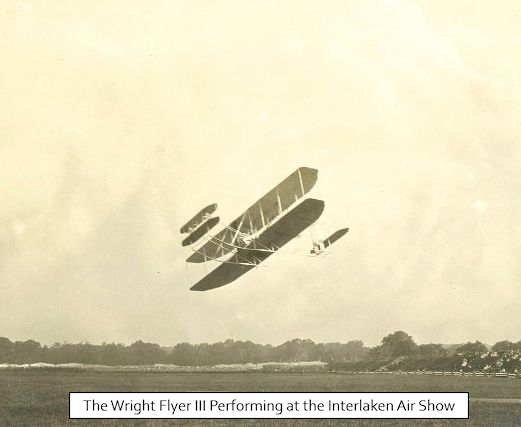

On August 10, 1910, the Wright Brothers came to Monmouth County to stage “America’s Greatest Aviation Meet.” It was designed to be a grand exhibition of manned heavier-than-air flight using the aviation system the Wrights created. The aircraft, called the Wright Flyer, on this occasion were flown by other aviators; the Wrights were present as observers and organizers. Over the next 13 days, large crowds in a specially built airfield in what is now Interlaken were thrilled by a number of aviation “firsts,” not all of which were positive achievements.

The Wright Brothers – Orville (August 19, 1871 – January 30, 1948) and Wilbur (April 16, 1867 – May 30, 1912) – were American aviation pioneers generally credited with inventing, building, and flying the world’s first successful motor-operated airplane. They made the first controlled, sustained flight of a powered, heavier-than-air aircraft with the Wright Flyer on December 17, 1903, near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The brothers were also the first to invent aircraft controls that made fixed-wing powered flight possible.

In 1904–1905, the Wrights further developed their flying machine to make longer-running and more aerodynamic flights with the Wright Flyer II, followed by the first truly practical fixed-wing aircraft, the Wright Flyer III. The brothers’ breakthrough was their creation of a three-axis control system which enabled the pilot to steer the aircraft effectively and to maintain its equilibrium

From 1904 to 1907, the brothers focused on improving their aircraft, working in secrecy to protect their patent rights. They told the world they were making longer and more complex flights, but witnesses were few and skepticism abounded, especially in Europe.

The Wright Brothers and the U.S. Army Signal Corps

By 1907, the Wrights were eager to sell their invention to government agencies. In November of that year, Wilbur met with the heads of the Army Ordnance Department, which was considering the application of aircraft for warfare, and the U.S. Signal Corps, which was tasked with evaluating the bids for the Ordnance Department. Although Fort Monmouth in New Jersey was home to the U.S. Army Signal Corps, the Wright Brothers, as far as we can determine, only interacted with the Corps in Washington, D.C.

The Signal Corps established criteria for the government aviation contract, and at that time, only the Wright Brothers had an aircraft capable of meeting them. The government, however, was obliged to entertain dozens of bids even though only one was able to fulfill the mission. Other opportunities loomed in Europe, and in 1908 the brothers split up to demonstrate their invention to audiences in the U.S. and Europe at the same time. Wilbur sailed for France; Orville would fly in the U.S.

The Wrights’ bid was finally accepted on February 8, 1908, pending successful demonstrations. Orville began conducting flights in Virginia for Signal Corps officers. Local press opined that the Army had gone daft, thinking that aircraft could ever have military applications.

Wilbur’s public demonstration flights near Le Mans, France, instantly proved that they had indeed conquered the challenge of flight, and the brothers became worldwide celebrities. Orville made his own demonstration flights, including one that lasted more than an hour, as well as others with passengers, namely, officers from the Signal Corps.

The successful demonstrations ultimately resulted in the Wrights receiving the full $25,000 the Army had earmarked for the winning bid. Problems with safety and reliability plagued the Wright Flyer in those early years, and the Wright Company would never become a major competitor in military aviation.

“America’s Greatest Aviation Meet”

In 1910, Orville and Wilbur traveled around the U.S. staging or attending aviation meets, to promote their business and bolster their patent claims. The brothers hired and trained two pilots to perform demonstrations, and worked with other early aviators to help show off their invention.

Walter Richard Brookins (July 11, 1889 – April 29, 1953) was the first pilot trained by the Wright brothers for what they called the “Wright Exhibition Team.” Frank Trenholm Coffyn (October 24, 1878 – December 10, 1960) was another member of the Team. Other aviators who flew at the meet were Ralph Greenley Johnstone (September 18, 1880 – November 17, 1910), and Archibald Hoxsey (October 15, 1884 – December 31, 1910). Johnstone and Hoxsey were known as the “heavenly twins” for their attempts to break altitude records.

The exhibition was staged in what was then Ocean Township, today the Borough of Interlaken, near where Interlaken Park now sits, although newspapers at the time reported that the event was held in Asbury Park. It had been conceived by local businessmen seeking to draw national attention to Asbury Park and the shore region.

This event followed a similar one that was staged in Atlantic City in July. Grandstands built for the meet could accommodate 10,000 spectators. The airfield was enclosed by a ten-foot-high canvas privacy wall so only those who paid the fifty cents admission could watch. The Asbury Park Aero and Motor Club sponsored the event, and offered $20,000 in prizes.

Each day of the show featured a variety of activities, such as kite flying and dirigibles, with the Wright Flyer being the star of the show. The day usually culminated with pilots attempting to set or break a record, e.g., in highest-ever altitude reached or longest amount of time airborne, or to establish another aviation first. The prize money was for the pilots who achieved these milestones.

The show got off to a dubious start. On the first day, Walter Brookins took off and achieved an altitude of 300 feet, and then crashed into the grandstands, injuring 11 people. This represented the first time in aviation history in which a crash involved spectators. Over the next few days, a debate arose over the high risks of aviation demonstrations. But the public was not put off and attendance soared.

Another milestone was the first night flight. Johnstone and Hoxsey each went aloft after 10:00 p.m. and landed safely, showing night aviation was viable. It was the first time the Wright Flyer had ever been flown at night by anyone.

On the third day, tragedy struck. A balloonist attempting a parachute jump accidentally fell from the basket in front of aghast spectators, dying immediately upon impact.

Later, another aviator flew a dirigible around the airfield, flying a little too low and shaving off the top of the roof of the administration building on the site, but no one was injured.

On August 20, the last day of the show, Frank Coffyn went aloft and flew a distance of about a mile, landed, and delivered a letter to a civic leader, who dashed off a reply that was then delivered via air back to the sender, representing the very first air mail delivery in U.S. history.

Because of bad weather, the show did not officially close until August 27. The organizers had realized their objective, as news coverage of the meet was widespread. Afterwards, the airfield and grandstands were taken down, thus ending Interlaken’s modest chapter in aviation history.

Sources:

Ciavaglia, James. (1970). Interlaken’s Air Show. Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., February 8, 1970, P. 18.

Kelly, Fred C. (1943). The Wright Brothers. Harcourt, Brace and Company, Inc., New York, N.Y.

Special to The New York Times. (1910). Wright Biplane Will Carry Five. The New York Times, New York, N.Y., August 16, 1910, P. 4.

Featured image: The Wright Brothers’ airplane in flight at the 1910 air show in Interlaken. Image source: Borough of Interlaken Historical Society, used with permission.

My grandfather took pictures of the event in 1910 and his uncle made a little book. I found this homemade book a few days ago while going through my grandfather WW1 letters to my grandmother. The Asbury Park Press had a story that day regarding an astronaut falling down the skies and hit an apple tree with his head. It also mentioned that he broke every bone in the body. There was a few pictures of planes .. it also looks like someone ripped a few pages off the book that was signed by the Wrights Brothers. My father had told me about when his father met the Wright Brothers.