Editor’s note: The author would like to thank Yvette Florio Lane, Ph.D., for her assistance with this important Timeline story.

On April 8, 1665, the English deputy-governor of New Amsterdam, Colonel Richard Nicolls, granted 12 white men, mostly Quakers from Long Island, the “patents” for a triangular parcel of land called the “Monmouth Patent” (also known as the “Navesink Tract”). This tract of land would later become Monmouth County, New Jersey.

The Monmouth Patent is noteworthy because it codified religious freedom in the colony 100 years before the Bill of Rights. But it also essentially established slavery as the basis for economic development of the region and began the process of displacement of indigenous inhabitants.

The Monmouth Patent extended from Sandy Hook to the mouth of the Raritan River, upstream approximately 25 miles, and then southeast to Barnegat Bay. It was first known as Navesink, likely after a band of the Lenape peoples who inhabited the area, and it was established into the settlements of Middletown and Shrewsbury, and later as Monmouth County. It was one of the first four counties in the proprietary East Jersey colony, along with Bergen, Essex, and Middlesex.

It is thought that calling the region Monmouth originated with the Rhode Island Monmouth Society, a group of investors who helped fund the purchase of the land, or from a suggestion from the settler Colonel Lewis Morris that the county should be named after Monmouthshire, in Wales, Great Britain. Other suggestions include that it was named for James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth (1649–1685), who had many allies among the East Jersey leadership.

The 12 patentees of Monmouth were William Goulding (Golder), Samuel Spicer, Richard Gibbons, Richard Stout, James Grover, John Bowne, John Tilton, Nathaniel Sylvester, William Reape, Walter Clark, Nichols Davis, and Obadiah Holmes.

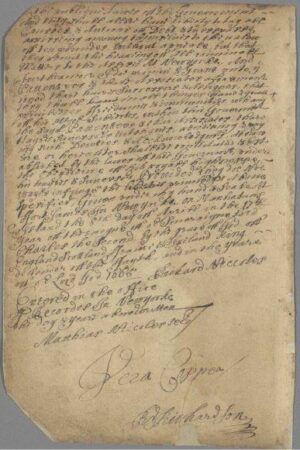

The Patent was recorded in the office of the Recorder of New York, November 8, 1665. It was the first such legal document recorded in the archives of the State of New Jersey in Trenton, as well as Monmouth County records in Freehold.

The issuing of the Monmouth Patent came during a period of nearly continuous warfare and strife between England and The Netherlands. From 1610 to 1673 there were three separate Anglo-Dutch wars and control over the New York-New Jersey region changed hands several times. The Dutch had claimed and settled New Netherland based on the explorations of Henry Hudson, who had been working for the Dutch West India Company when he first came to the Raritan Bay area in 1609. The English believed that they had a prior claim from the explorations of John Cabot in the 16th century.

In March of 1664, King Charles II of England, Scotland, and Ireland resolved to annex New Netherland and “bring all his Kingdoms under one form of government, both in church and state, and to install the Anglican government as in old England.” On August 27, 1664, four English frigates led by Colonel Nicolls sailed into New Amsterdam’s harbor and demanded that the city surrender the fort at the tip of Manhattan that served as the seat of the New Netherland colony. The lack of adequate fortification, ammunition, and manpower made New Amsterdam defenseless, and the Dutch West India Company had been indifferent to previous pleas for reinforcement of men and ships against “the continual troubles, threats, encroachments and invasions of the English neighbors.” New Amsterdam surrendered to Nicolls on September 8, 1664 and he assumed the position of deputy-governor of New Netherland for the crown. He instituted a legal system centered on English common law and issued conditions upon which plantations and land grants would be created.

During this time, both the Dutch and the English governments used a system of “patents” to grant lands in the new colony to settlers; the royal government offered a land patent for a specific area, and the recipient was responsible for negotiating a purchase with representatives of the local tribes, usually the sachem (high chief).

Although efforts were apparently made to ensure that dealings with the land’s indigenous inhabitants at least carried the appearance of propriety, in fact, the Lenape peoples unknowingly signed away their property rights, with permanent consequences.

Were the Lenape Treated Fairly?

In 1665, no white person lived in what is now Monmouth County. A group of men from Long Island visited the Raritan Bay region and had designs on settling the coastal area around Sandy Hook. Before issuing a patent, Governor Nicolls wanted to hear personally from the Lenape sachems that this was an amenable arrangement and that they had been paid in full. Accordingly, a group of the would-be patentees and sachems went to New York City to meet with the governor. After receiving the assurances he desired, Governor Nicolls was prepared to grant the patent.

This narrative of the sequence of events suggests that the Lenape were treated fairly in the transaction. That’s not how they view it. The official position of the tribe today is:

Our ancestors were asked to sign treaties giving up the land, but they had no idea that they were actually selling land any more than you would think someone could sell air. The belief was that all land was put here by the Creator for use by his children, and that you should not be stingy with it. The Lenape of those days thought they were granting the Europeans the use of the land for a while. They in turn received gifts for the use of the land, like rent. Only later did they come to understand the European concept of private land ownership.

Did the English know that the Lenape approached the deal with a fundamentally different understanding of the terms of the contract? In other words, did Nicolls et al., deal in bad faith, knowing full well that the Lenape did not realize they were signing away their land rights in perpetuity?

It’s noteworthy that some early colonial leaders, such as William Penn, were avowed in their Quaker values of treating all humans with Christian charity, and therefore, insisted that all transactions with indigenous tribes be on the up-and-up. However, the question remains: did they know they were tricking the natives into a permanent relinquishment of land ownership rights?

The answer is complicated. While native tribes typically did not recognize individual ownership of land, the concept of individual property ownership rights had existed for millennia. For example, horses belonged to one tribe member only and were often a sign of status. Blankets, knives, and even slaves were considered exclusive personal property of native tribe members at this time. The English at that time looked upon the Indians as pagan savages, a lower class of humans, who were perceived, inaccurately, as not developing or improving the land. One of the chroniclers of the Plymouth Plantation settlement said that “it is lawful now to take a land which none useth and make use of it.” And the other sentiment that proved to be especially insidious over time was expressed by John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1628: “If we leave them [enough land] sufficient for their use, we may lawfully take the rest, there being more then [sic] enough for them and for us.”

Little wonder that, to this day, the Lenape believe they were egregiously wronged.

Religious Freedom, but also: Slavery

The patentees, mostly Quakers, some of whom had experienced persecution for their beliefs, requested that the legal document that would form the Monmouth Patent include a guarantee of unrestricted religious tolerance for settlers under it. The language read, “…any and all persons, who shall plant and inhabit in any of the land aforesaid that they shall have free liberty of conscience, without any molestation or disturbance whatsoever in their way of worship.”

But the document also required settlers to maintain “an able Man servant or two such weaker Servants,” and additional acres were granted to settlers with more servants. The government’s intent was to develop the land, not merely transfer title. Servants were needed to help build homes, clear land, cut wood, plant and harvest crops, tend livestock, forage for food, and so on.

Finding white Europeans to fill these servant roles was considered all but impossible. The expense of bringing someone across the ocean and then having to pay wages was financially untenable for most people trying to eke out a living from the land. According to Graham Russell Hodges, colonists early on advertised in Europe for workers, but often found that indentured servants ran away before the end of their contracts. Considered free white men, these servants could not be forced to work under the same conditions as enslaved people. And, indentured servant contracts of that era were typically a commitment of about 6-7 years, while slaves were bonded laborers for life. Some Indians were enslaved, but over time, Black Africans were increasingly violently exploited as the main labor force in a practice of enslavement that continued in Monmouth County for 200 years.

The Monmouth Patent reveals the conflicting values of colonial settlers seeking a better life, and these early residents have been celebrated ever since as our area’s founding fathers. Less well appreciated is the human price paid by others, specifically by Blacks and Indians, whose forced sacrifices were crucial to the success of the new settlement.

Sources:

Descendants of Founders of New Jersey. Available: https://www.njfounders.org/history/monmouth-patent-and-patentees

Dexter, Henry Martyn. (1622). Mourt’s Relation or Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth. Available: https://factreal.files.wordpress.com/2009/11/heritagepilgrimsmourtsrelationjournalbywinslow.pdf

Ellis, Franklin. (1885). History of Monmouth County, New Jersey, Part I. Originally published by R.T Peck & Co., Philadelphia, Penn. Reprinted in 2017 by The Apple Manor Press, Markham, Va.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Lenape or Delaware Tribe. (2021). Official Web Site of the Delaware Tribe of Indians. Available: http://delawaretribe.org/blog/2013/06/26/faqs/

Hodges, Graham Russell. (1997). Slavery and Freedom in the Rural North: African Americans in Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1665-1865. Madison House Publishers, Lanham, Md.

Salter, Edwin. (1890, 1997, 2001). Salter’s History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties New Jersey. A facsimile reprint, published 2007. Heritage Books, Inc., Westminster, Md.

Smith, Samuel Stelle. (1983). Lewis Morris: Anglo-American Statesman. Humanitarian Press, Inc., Atlantic Highlands, N.J.

Nova Caesarea: A Cartographic Record of the Garden State, 1666-1888. (2014). Princeton University Library. Available: https://library.princeton.edu/njmaps/index.html

Winthrop, John. (1628). Reasons for the Plantation in New England, ca. 1628. Available: https://www.winthropsociety.com/doc_reasons.php

Photograph of the Monmouth Patent. Image courtesy Monmouth County Historical Association, used with permission.

Please give me the source that states that African American slaves were present when the original Monmouth patent was issued. Also, please give me the source where stated that Patent signers had African American slaves.

Hodges, Graham Russell. (1997). Slavery and Freedom in the Rural North: African Americans in Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1665-1865. Madison House Publishers, Lanham, Md.

Geffken, Rick. Stories of Slavery in New Jersey. The History Press, Charleston, SC, 2021.

can you please show me in the book where it states with proof that the patentees had slaves? the patentees we are discussing..not residents after the patentees.

We do not state anywhere that the patentees owned slaves. We state that the document clearly led to the introduction of slaves into the region, which is accurate.

We do not state either of those things in this story. We state, accurately, that the terms of the patent LED to slavery in the region. Read it closer, without your righteous indignation, we don’t make any claims about the patentees being slaveowners.