If we let him out on the street, he’d be dead in a half an hour.

Unnamed federal agent, on the need to protect star mob witness Joe Valachi

Vito Genovese was among the most feared mobsters in the history of organized crime, and yet two people dared risk his wrath and testified about the mafia, its leaders, secrets, and inner workings. He provoked the first two occasions in which mafia insiders made national headlines by violating omertà, the ancient southern Italian code of silence.

One of those insiders was Anna Genovese, Vito’s estranged wife, who testified during divorce proceedings that she had initiated. In open court she spoke about his various rackets, his money, and the lavish lifestyle he led. The other was Joseph Valachi, a longtime soldier in the New York City mafia. Each broke the mafia code of silence while in Monmouth County and made national headlines for blowing the lid off organized crime in America. And while the entire nation expected these prominent stool pigeons to receive the mafia’s ultimate punishment for snitching, both lived long lives and died of natural causes.

Who was Joe Valachi?

Joseph Michael Valachi (September 22, 1904 – April 3, 1971) was a lifelong New Yorker who became involved in organized crime at a young age and spent his entire adult life as a “made man,” that is, an inside member of one of New York’s “Five Families,” the governing council that oversaw all of the Italian American rackets in the region.

Vito Genovese and Valachi were both members of the Luciano crime family, headed by the “boss of bosses,” or capo di tutti capi, Charles “Lucky” Luciano. Valachi had been a member of other families in which the bosses were eliminated, and soldiers like Valachi were then folded into the conquering family.

Genovese had fled to Italy in 1937 to avoid facing murder charges. In 1944, he was arrested in Italy and brought back to New York City to face those charges, which were dropped when the key witness was unable to testify due to having been murdered, poisoned while in protective custody. After Lucky Luciano was deported to Italy in 1946, Frank Costello took over the family, with a newly free and repatriated Genovese a part of his crew.

Soon, Genovese began plotting his ascension within the Luciano family. He had rivals eliminated one by one, and finally sent one of his hit men, Vincent “The Chin” Gigante, to take out Frank Costello. Gigante’s shots only grazed Costello, who survived. But Costello was fearful for his life thereafter and retired from running the family, paving the way for Genovese to take charge.

As a result, Valachi then became one of Genovese’s foot soldiers. Among the 33 murders attributed to Valachi, one was Steven Franse, who was Anna Genovese’s partner in running several gay nightclubs in New York City, some of which were not on the mob’s books. Vito felt that Franse had not been sufficiently devoted to the cause of taking care of Anna while he had been in exile, such that she and Vito had drifted apart. Franse was murdered on June 19, 1953; Valachi confessed to hiring the killers and coordinating the hit, on Genovese’s orders.

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics was far more vested in taking on the Five Families compared with the FBI in the 1950s. In 1959, the New York City office of the FBI had only four agents devoted to organized crime, while some 400 were focused on ferreting out communists from the ranks of government and the military. But thanks to the impetus of New York Governor Thomas Dewey and U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the bureau’s focus shifted dramatically, and by 1962 the office had 150 agents looking into racketeering.

Over time, the Bureau of Narcotics developed a network of informers and was eventually able to get drug trafficking convictions against both Vito Genovese and Joe Valachi.

Genovese was sent to the United States Penitentiary, Atlanta (USP-Atlanta), where he was set up in the best available prisoner quarters and was able to continue running the family from his cell. He was surrounded by his own hand-picked lieutenants and the prison housed another 90 or so incarcerated made men who all called him boss. Even the prison exercise yard had been altered to include a bocce court, where it was a challenge for those who played the Italian lawn-bowling game to pretend to be awful at it in order for Vito, a poor bowler, to prevail in every contest.

According to Valachi, Genovese was “the absolute ruler of this little empire…the arbiter of all disputes, the dispenser of all favors. One dared not address him unless permission was first granted. One backed away from him after speaking to him.” Since he only deigned to come out of his cell twice a week, appointments had to be arranged through intermediaries far in advance.

Valachi ended up being sent to USP-Atlanta as well, where he reconnected with Genovese. They were close enough that Genovese had served as best man at Valachi’s wedding. Together they were able to figure out how each had been set up for their narcotics convictions, and Genovese invited Valachi to join him and his other four key henchmen as cellmates in his spacious cell, built to hold eight.

During this time, the feds had continued taking Valachi from his cell to various places for interrogation. While he refused to tell them anything useful, he became aware that rumors were circulating back in prison that he was cooperating with authorities. Jealousies among the other Genovese underlings led to whispers that Valachi was breaking omertà by providing information to the feds in return for a reduced sentence. He had done no such thing – at least, not yet.

In a prison with almost a hundred mafia soldiers, mob justice was a normal part of life for men like Valachi. Old grudges, vendettas, and suspicion of snitching were among many sources of prison violence.

Valachi began to see mortal threats all around him.

On one occasion, a Genovese lieutenant brought Valachi a steak sandwich, smuggled from the cafeteria. Valachi believed it was poisoned, threw it away, and thereafter refused to eat anything other than packaged foods. Others tried to get Valachi into the shower room—a favorite venue for mob prison hits—and where he knew he could be easily cornered. So he went without bathing.

During this time, Genovese recited to Valachi a dull parable about how if a barrel of apples had one bad apple, that bad apple had to be removed or it ruined the whole barrel. Genovese then made a gesture of kissing Valachi on the cheek. One of the observing mafia lieutenant cellmates informed Valachi that he had just received “the kiss of death.”

“You got to understand that Vito was always talking in curves,” said Valachi. “It’s tough to figure out his real meaning.” But after that incident, Valachi sat alone at the lunch table formerly reserved for New York hoodlums—shunned—and realized he had become the target for whatever was about to happen to him.

The last of Joe Valachi’s murders took place at USP-Atlanta. Valachi killed a man he believed was trying to murder him at Genovese’s behest, and attacked him first. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a case of mistaken identity, and Valachi had killed the wrong made man. Every mobster at USP-Atlanta would be out to get him now.

At his next interrogation, a federal agent casually let it slip that they had learned that Valachi was next on Genovese’s hit list. Valachi then asked to be placed in solitary confinement at USP-Atlanta for his own protection.

Then he made the fateful decision to violate his sacred oath, and got word to the federal authorities that he was ready to talk. He was well aware that he was the first such person to break this code of silence. During his lengthy testimony, Valachi would repeatedly emphasize that in his view, since he had been targeted for death without cause, it was Vito Genovese who was the true traitor to the family. He didn’t want Genovese dead, he wanted him to have to face the consequences for his actions, which Valachi felt had ruined “this thing of ours.”

And talk he did. They brought him to the Westchester (New York) County jail first, where he was interrogated for several months. Westchester was known to be where the police housed stool pigeons and Valachi insisted on being moved. Meanwhile, Genovese put out a $100,000 contract for the permanent removal of Valachi. One federal agent later remarked: “If we let him out on the street, he’d be dead in a half an hour.”

Joe Valachi Comes to Monmouth County to Rat on Vito Genovese

On February 5, 1963, the Department of Justice transferred Valachi to the “Confinement Center”at Fort Monmouth, better known as “the stockade.” The Confinement Center was a temporary building located near the base movie theater that was a part of the World War II expansion of Fort Monmouth. The stockade, ironically, was about ten miles from Atlantic Highlands, the longtime residence of Vito and Anna Genovese, and an area that still teemed with Genovese crime family members.

Valachi had been taken to the fort under total secrecy, and no one knew his whereabouts for five months. Then, while eating at a diner in Long Branch, a base soldier noticed a photo of Valachi in the New York Daily News and said, “hey I know that guy, we’ve got him at the fort!” And the secret was out. Ten days later, the paper ran the story and caused a national sensation.

Knowing that the world was about to find out where the feds were hiding Valachi, officials at Fort Monmouth immediately increased security. An unnamed source told the Red Bank Register that “last night,” meaning August 14, 1963, security “was tightened to practically World War II proportions.”

Valachi was housed in the stockade, a single-story cement block building near Oceanport. There he was held in the officer’s section and had the run of two cells, with a third used by a corrections officer, with Valachi monitored around the clock. He was guarded by a select contingent of corrections officers from the federal penitentiary at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania.

Military police arrested one person overlooking the stockade and military aircraft turned back a photography plane attempting to take pictures.

Later, a public affairs officer at Fort Monmouth would say only that “Valachi has been held at the request of the Department of Justice and has been kept at Fort Monmouth which is closely guarded at all times. The Army will have no other comment regarding him.”

The public information officer said that while he could not recall any previous time when the Signal Corps headquarters was ever used to house or protect a federal prisoner of such notoriety, he believed that Fort Monmouth was “well equipped” for such duty. “We can easily get up to maximum security here. It is no problem.”

Although Valachi was reported to be behaving normally with no incidents, one guard later said, “We just couldn’t predict Valachi’s mood. Some days he would be happy and other days sorrowful. But we knew he was always scared. Even worried when planes flew over the stockade. He thought they were sent by his enemies to drop a bomb on him.” According to news reports, he became known as “the man in the iron mask” among the military inmates in the stockade because of his seclusion and refusal to participate in stockade activities.

Valachi was supposed to be at Fort Monmouth for about three weeks, but remained there for seven months, telling the feds everything he knew about the inner workings of the organized crime families. Valachi was naming names, detailing organizational structures, and providing insight into rules and operating norms. He explained how mob bosses like Vito Genovese could remain at a distance from the crimes committed by family members on their orders. It was the first time any made man, or formal member of “La Cosa Nostra,” had ever spoken publicly in such a manner. In fact, it was during this time that Valachi himself informed the feds that no one in organized crime ever used the term “mafia,” and that the correct name was La Cosa Nostra, loosely translated as “this thing of ours.” The English version was often used as a coded reference, as even the phrase La Cosa Nostra was never to be spoken.

Valachi’s Fort Monmouth testimony was so important that he even received a personal visit from United States Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. In June of 1964, Kennedy said that Valachi’s testimony was “The biggest single intelligence breakthrough yet in combating organized crime and racketeering in the United States.”

Not everyone was thrilled to have the notorious informer residing in the area. The president of the Eatontown Chamber of Commerce said, “I don’t know what the Army has to do with hiding a criminal. I did not know Fort Monmouth was a Bastille. It’s a bad reflection on the fort and on New Jersey.” Whether due to local opposition, or the increased risk now that Valachi’s whereabouts were known, or because he was wanted elsewhere to testify, Valachi would not be in Monmouth County much longer.

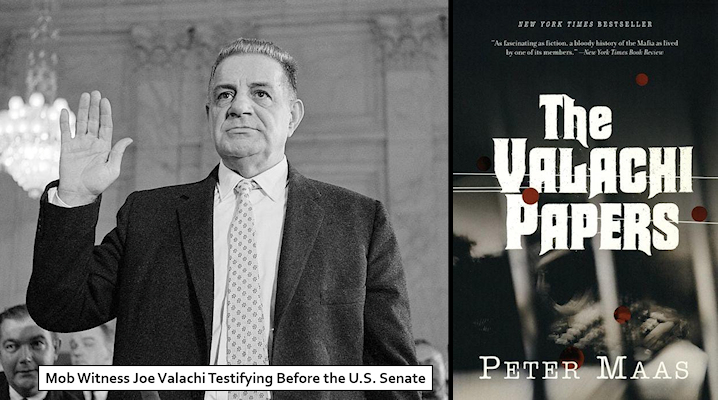

On August 31, 1963, Valachi was transferred from Fort Monmouth to Washington, D.C., to testify before a senate subcommittee in what became known as the Valachi Hearings. He was housed in the Washington, D.C. jail during this time.

The Aftermath

The impact of Valachi’s testimony is difficult to measure. Historians debate whether the information he provided helped bring down the notorious mob boss Carmine Persico. But he provided the first clear picture of how organized crime worked and who was running what.

“What he did is beyond measure,” said William Hundley, head of the Department of Justice organized crime division. “Before Valachi came along, we had no concrete evidence that anything like this actually existed. In the past we’ve heard that so-and-so was a syndicate man, and that was about all. Frankly, I always thought a lot of it was hogwash. But Valachi named names. He revealed what the structure was and how it operated. In a word, he showed us the face of the enemy.”

The Justice Department first encouraged, and then blocked, publication of Valachi’s memoirs. Journalist Peter Maas was able to win Valachi’s confidence, and produced a biography that combined what was in Valachi’s voluminous testimony as well as his own interviews, and this was published in 1968 as The Valachi Papers. It was a blockbuster best-seller, and it formed the basis for a film of the same title, starring Charles Bronson as Valachi and Lino Ventura as Vito Genovese. Peter Maas later called it “one of the worst films ever made.”

Throughout the publication of The Valachi Papers, and the national sensation it caused, Valachi remained unrepentant. “The more I live, the more shame it is for Vito,” he said.

On April 3, 1971, Valachi died of a heart attack while he was serving his sentence at the Federal Correctional Institution, La Tuna, in Anthony, Texas. He was buried four days later at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Lewiston, N.Y.

Sources:

Harnes, John A. (1993). From Pigeons to Computers. Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., April 8, 1993, P. 32.

Maas, Peter. (1968). The Valachi Papers. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, N.Y.

Tighten Security at Fort; Army Quiet on Valachi. (1963). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., August 15, 1963, P. 1.

Valachi’s Song has Gangland in Lather. (1963). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., August 18, 1963, P. 1.

Leave a Reply