Editor’s note: This article was first published in 2020; it has been updated as of December 2, 2022, and on December 16, 2024, adding information provided by George McDonald, son of Private Joseph McDonald, switchboard operator at the Opana Point information center and one of the four principals involved in this story. Monmouth Timeline is grateful to George McDonald for reaching out and providing valuable insights into this event.

By John R. Barrows

On December 7, 1941, two members of the U.S. Army Signal Corps stationed at Oahu, Hawai’i, were utilizing the newest electronic long-range detection system when they observed what appeared to be a “large flight of planes” heading toward Pearl Harbor early in the morning. They immediately reported their findings, but were told “don’t worry about it,” and the warning went unheeded. Moments later, planes of the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor, inflicting devastating losses and touching off America’s involvement in World War II.

These two men were thrown together by destiny, connected forever by what they saw and did that morning. Their lives would be forever changed, but not in the same ways. One went on to immediate reward and acclaim, while the other was relegated to the shadows. Both men lived in Monmouth County at one time, one for a matter of months, the other for more than 30 years. And both men were depicted in major motion pictures made about Pearl Harbor, but the two versions of the story are significantly, dramatically different.

Everything went right for one of the two Army privates after December 7, while the other had to fight for recognition and credit. But is it possible that the man relegated to the shadows got the last laugh? And what might have happened if the warning had been taken seriously?

The Radar at Pearl Harbor

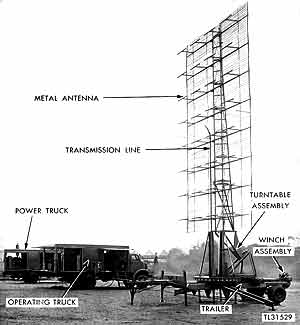

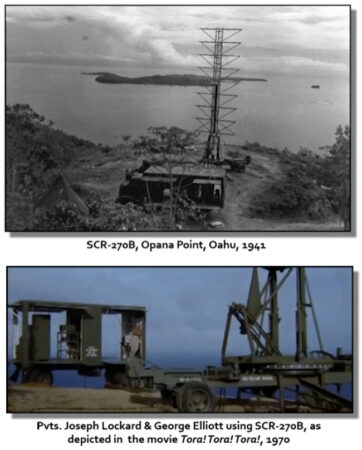

In December 1939, the 515th Army Aircraft Warning Service (AWS) began using a new technology system to defend American territory. It employed the SCR-270B, the newest U.S. long-range aircraft search apparatus, created at the Signal Corps Laboratories at Fort Monmouth in 1937. By 1941, the system was still so new it didn’t even have a name yet, and was so secret it had been given a standard Signal Corps Radio (SCR) number, the same as every other radio or other communications device developed by the Signal Corps. It would eventually become known as “radar,” standing for “radio detection and ranging.”

The AWS established six mobile radar detector sites on Hawai’ian islands, one on Kaawa, Kawailoa, and Opana Point in Oahu, and at Koko Head, Fort Shafter, and Waianae in Honolulu. The Opana Point setting is a location 532 feet above sea level with an unobstructed view of the Pacific Ocean. The SCR-270B set comprised four trucks, carrying a transmitter, modulator, water cooler, receiver, oscilloscope, operator, generator, and antenna. The antenna generated an electrical pulse into the sky. If anything interrupted the electrical beams, the radar’s oscilloscope reflected the object as an echo. Some echoes appeared constantly, such as from the nearby hills and cliffs, but others were temporary, and those were the ones the operators focused on. These signals showed and tracked airplanes intersecting the radar transmitter’s beams.

On December 7, 1941, the Opana Point site was manned by Private Joseph L. Lockard, 19, and Private George E. Elliot Jr., 22.

Joe Lockard was born on October 30, 1922, in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. He enlisted in the U.S. Army on August 18, 1940, and was sent to Schofield Barracks, Hawai’i, for basic training in December 1940. After completing basic training and basic radio operator training, he was assigned to the Army Signal Corps and was then trained as a radar operator. Opana Point was his first assignment as a radar operator.

George E. Elliot Jr., a native of Chicago, joined the Army in 1940 and first attached to the Army Air Corps before transferring to the Signal Corps early warning system. He was an apprentice radio operator on the day of the Japanese surprise attack.

Lockard and Elliott were working the standard Sundays-and-holidays shift, from 4:00 a.m. until 7:00 a.m. They were brought up to the station the night before and slept there in pup tents. They operated the system for three hours, and then took the same shuttle truck back down to their base. On December 7, their shift was up, but the truck had not yet arrived. The two kept the system up and running so Elliott could get a little more experience. Around 7:04, they saw what appeared to be a large number of airplanes coming from the northeast at high speed. Elliott immediately turned the system over to Lockard, his trainer, who thought the system might be malfunctioning. Elliott plotted the incoming planes while Lockard determined that the system was working fine, and that they were indeed seeing a large quantity of unexpected airplanes.

Accounts of What Happened Vary Greatly

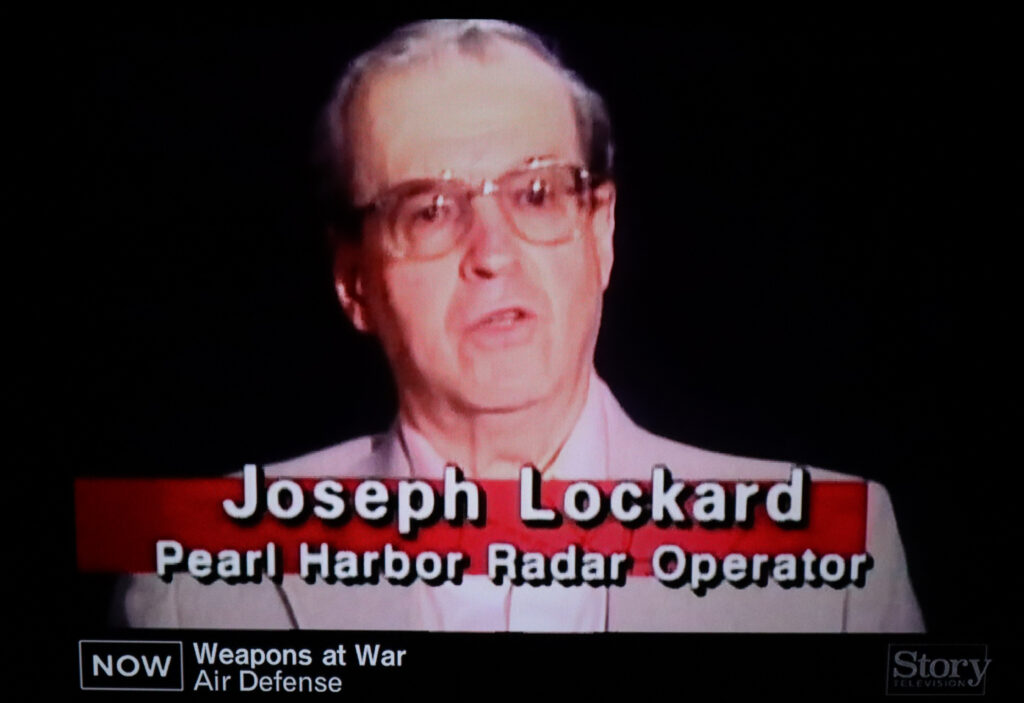

According to every other telling, the two men kept the system running because the breakfast truck was late, and Elliott wanted the extra work, but in the official Army record for Joe Lockard’s medal citation, it said that Lockard had requested permission the night before to keep the system running late, so Elliott could get more experience. Joe Lockard was interviewed for a television documentary called Weapons at War: Air Defense, and said that they’d kept operating the system because the truck was late. Does this mean Lockard’s medal was based on inaccurate or false information?

Elliott later described what he saw as “something completely out of the ordinary” on the screen: a huge blip, due north, 137 miles out, approaching at three miles a minute. In testimony before the Army Pearl Harbor Board, Elliott said that Lockard had noticed the blip.

A call was made to the Information Center at the AWS base, as per standard procedure when the SCR-270B operators saw anything suspicious. Some accounts have Lockard making this call, others have Elliott making the call, while still others assert that Elliott made the first call, and Lockard made a follow-up call, or that Lockard answered a return call. Elliott testified before the Army Pearl Harbor Board that he had “suggested to Lockard that they call up the Information Center…After some debate between them, Lockard did call the Information Center…”

Either way, Lockard and Elliott notified the Information Center at Fort Shafter, which was still operating on the night shift. On duty was switchboard operator Pvt. Joseph McDonald and Army Air Corps Lt. Kermit Tyler. Lockard told Tyler that the radar blips suggested “an unusually large flight – in fact, the largest I have ever seen on the equipment.”

Tyler replied, “Don’t worry about it.” Tyler, a veteran pilot but a man who had been given no training on the radar system, assumed the planes were B-17s from the west coast, bombers from Hickam Field near Honolulu, or a squadron of Navy patrol planes. It was now 7:20 a.m.

Lockard and Elliott continued to follow the temporary echo until 7:39 a.m., when it was lost in the permanent echo created by the surrounding mountains. A short time later, the truck came to take them to breakfast. About ten minutes later, the first bombs started falling on Pearl Harbor.

Lockard and Elliott could see the oily black smoke down in the harbor on their way to camp; back at camp, they knew immediately what it was they had seen on radar.

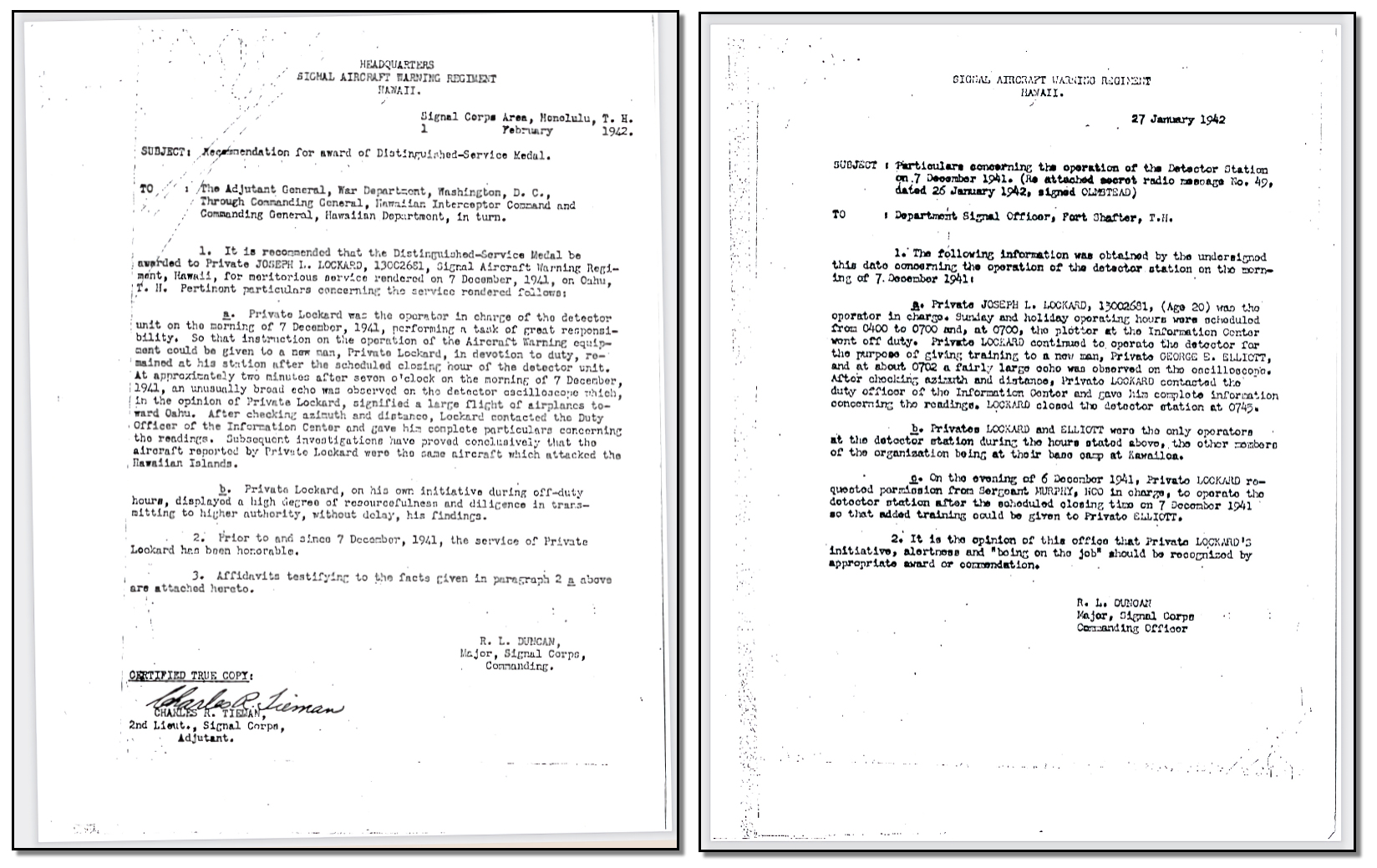

Lockard, 19 years old at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, had been in the Army a little more than a year. In the aftermath of the attack, he was given almost complete credit for spotting and reporting the approaching Japanese aircraft. He was promoted to sergeant and sent to Officer Candidate School and awarded the Distinguished Service Medal (DSM). The DSM is not to be confused with the Distinguished Service Cross. The latter is awarded for heroism in wartime, while the former is given as a recognition for soldiers anywhere within the Army who have gone above and beyond in doing their job at the highest level.

Lockard’s letter of recommendation credits him with having been the one to interpret the blips seen by Elliott. Elliott is only referred to in Lockard’s recommendation as “a new man,” and the document states that Lockard remained at the station after closing time “in devotion to duty,” which conflicts with the notion that he’d planned all along to stay late. George Elliott is disregarded entirely in Joe Lockard’s commendation, and there is no mention of Lockard serving as a trainer or having a trainee.

Private Joseph McDonald, Switchboard Operator

Author Walter Lord in his book, “Day of Infamy,” relates this story as told by Private Joseph McDonald, who is briefly shown in Tora! Tora! Tora! but does not play an important role in the film’s version of events. According to Lord, McDonald told him Lockard and Elliott normally made 25 radar contacts during their regular 4:00 – 7:00 a.m. watch, but this Sunday there was hardly anything in the skies. As long as the breakfast truck was late, Elliott wanted to practice operating the set. After two weeks in the outfit, he could do the plotting pretty well but was still not as adept at operating the system; Lockard was willing to teach him.

After they saw the mass of blips, Elliott tried calling the information center and finally got through to McDonald, the center’s switchboard operator. McDonald said that Elliott told him, “There’s a large number of planes coming in from the north, three degrees east.”

McDonald took the message to Lt. Tyler and they discussed what they should do; Tyler didn’t think it was worth taking action. McDonald called back to Opana and Lockard told him they were certain they were seeing a large number of airplanes headed straight for Oahu. Lockard asked to speak with Tyler and McDonald had to convince the lieutenant to take the call.

At this point Lockard was ready to shut the system down but Elliott wanted more practice and so they continued tracking the incoming blips until 7:39 a.m., when the incoming planes were just 22 miles away. At that point the blips went into a “dead zone” caused by the hills around them, the breakfast truck arrived, and they went back to base.

Private Joseph McDonald, as told by his son, George McDonald.

This story focuses on Joseph Lockard and George Elliott but there are four men who play equally important roles in this event, Joe and George, Lieutenant Tyler, and Private Joseph McDonald. With post-war reports varying in terms of who did or said what during those fateful forty minutes, Private McDonald’s account of events provides vivid clarity. His son, George McDonald, has spent most of his life preserving the memory of his father and his role in the Pearl Harbor saga.

“He considered going over Tyler’s head but thought, who would listen to a Private?” said George, via email. He was told shortly after the attack that he needed to keep his mouth shut regarding this incident or he could find himself in jail.”

According to George, Tyler had been told by his commanding officer, Major Berquist, to call him if anything unusual took place. Joseph McDonald approached Lt. Tyler three times to urge him to follow these instructions, to no avail. He also suggested recalling the plotters and notifying Wheeler Field of the massive incoming flight.

Regarding the variations in first-hand accounts of what happened that morning, George said, “Understand these were all young soldiers…they were all caught up in the shock of attack.”

According to George, the Shafter Information Center personnel had a betting pool as to what date the Japanese would attack. “When my father entered his tent after his shift, he woke up his tentmate Richard Schimmel to tell him, ‘Shim the Japs are coming.'”

Over the years, George McDonald made it a point to meet and then stay in touch with Joe Lockard, George Elliott, and Kermit Tyler. “I knew Joe as an old man. He considered this as part of his life and not the pinnacle of his life. George Elliott was surprised when I shared my father’s account…He saw my father’s role as being overlooked also. My father did see Tora! Tora! Tora! and wasn’t impressed by the Opana Point radar depiction.” In the film, McDonald’s role is very brief and does not show the initiative he took and the extent to which he agonized over what to do as the seconds ticked away. “He was in the first [American] battle of World War II, Pearl Harbor, and the last, Okinawa.”

On July 12, 1942, Lockard was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Signal Corps, one day ahead of the rest of his class of 855 new Signal Corps officers at Fort Monmouth.

Lockard left the Army in December 1945 and held a variety of jobs. He started first as a trackman for Pennsylvania Railroad; when he left, he was a maintenance supervisor. He worked for Sylvania Electric and then AMP Incorporated, from which he retired in 1986. He was an inventor for AMP and held some 30 patents for electrical switches and connectors.

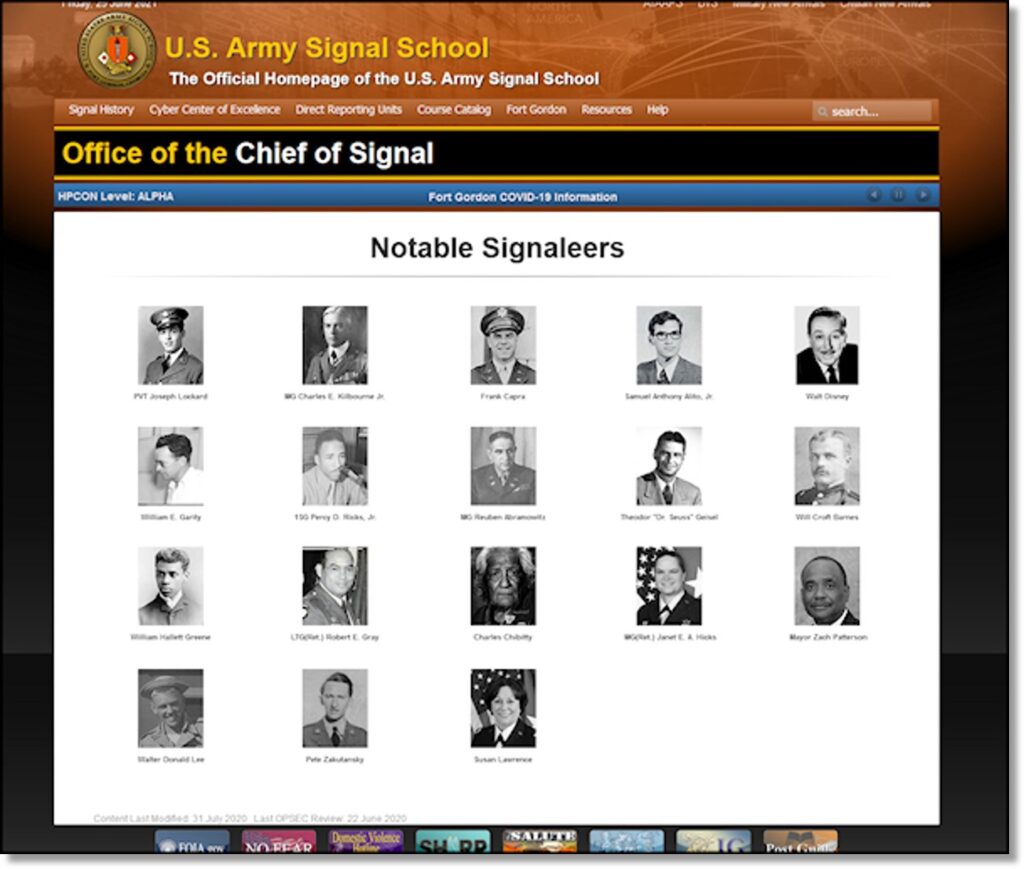

A Notable Signaleer

In addition to his promotions and medal, Joe Lockard is honored as a U.S. Signal Corps “Notable Signaleer,” one of just 18 such honorees. Other Notable Signaleers include award-winning film director Frank Capra (It’s a Wonderful Life), current U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., Walt Disney, and even Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss. Both the Army and Navy enlisted top creative minds from show business during World War II and used them to create propaganda films, document major events, and generally support the war effort. Also among the Notable Signaleers are a Medal of Honor recipient, and several Signal Corps leaders who marked milestones in diversity. In the Notable Signaleers writeup on Lockard, George Elliott is mentioned as having been there right alongside Lockard, the entire time, but only Lockard received the Signal Corps honor.

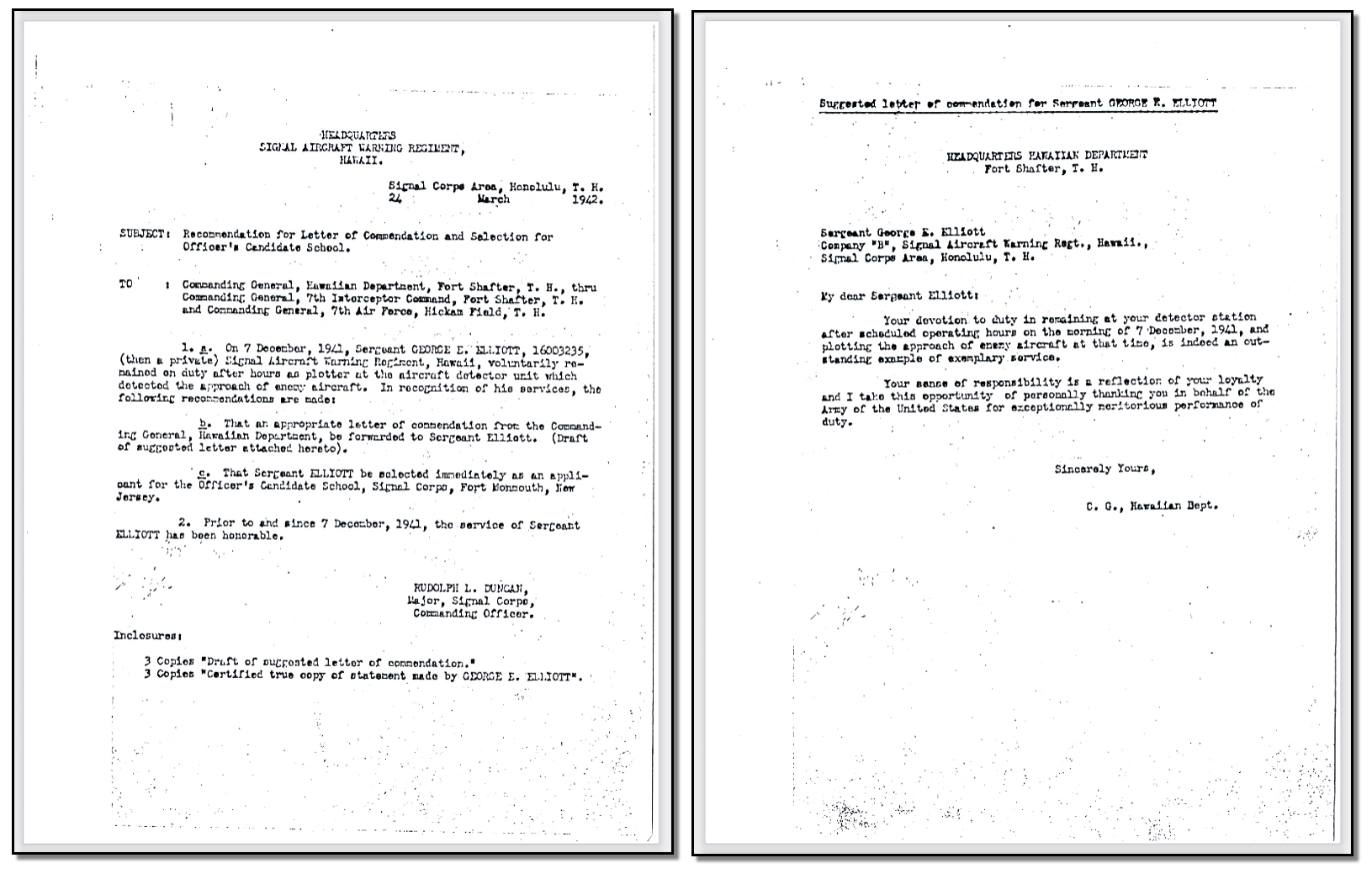

Like Lockard, George Elliott was promoted to sergeant after December 7. Lockard received his medal in February of 1942. In March of 1942, Elliott was given a letter of commendation and was selected to attend Officers’ Candidates School at Fort Monmouth; however, he “just missed” getting a commission. But Elliott did meet the former Margaret Wright of North Long Branch, and they were married. George served in the Army stateside at a number of posts (some reports say he spent the rest of the war at Fort Monmouth) until his discharge as a sergeant in 1945.

George Elliott was relegated to being a footnote to the Opana Point event until joint Congressional hearings on the attack in 1946. Elliott was considered a “surprise witness” who showed up unannounced and apparently uninvited on the final day of the hearings.

After his testimony, and lobbying from senators, the Army awarded Elliott the Legion of Merit for his actions on that day, but he refused to accept the honor, saying he should not be given a lesser recognition than Lockard. Years later, he said that he had refused the honor because they were just doing their jobs, looking at screens, and that it might be different if lives had been saved. After the war, he decided to return to Long Branch, where he lived for 33 years, working for New Jersey Bell Telephone.

The Pearl Harbor Movies – John Ford’s December 7th (1943)

Pearl Harbor ranks as one of the most important and well-known events in American history, so it is not surprising that two different award-winning docudramas have been produced, by some of the most famous names in movie history. Docudramas are essentially re-enactments using actors, but are intended, generally, to adhere closely to established historical facts.

The use of radar to detect the incoming Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor was included n two award-winning movies that presented very different versions of these events.

The first came out in 1943, while the U.S. was embroiled in combat in Africa, Asia, and Europe. The Department of the Navy wanted a film to be produced that presented an unvarnished accounting of what had happened on December 7. Ultimately, legendary Hollywood film director John Ford was brought in to lead the project. Ford was at the top of his craft at the time, following the success of his blockbuster hits Stagecoach (1939) and The Grapes of Wrath (1940).

But Ford’s version of Pearl Harbor, entitled December 7, 1941, was not well received when it came out. He had signed on as producer and initially hired Gregg Toland to direct. Toland was one of Hollywood’s most celebrated cinematographers, with noteworthy credits including Citizen Kane (1941). But December 7th, 1941, was the first, and only time Toland ever directed a film. Ford ended up firing him and taking over the director’s chair.

The original film was 82 minutes long, with most of the first half devoted to a telling of the history of Japan and Hawai’i and showing the Japanese people in very stereotypical ways, e.g., with thick round eyeglasses and buck teeth. The film also dwelled at length on the concern that native Hawai’ians of Japanese ethic origin were acting as spies and saboteurs, and essentially suggesting that the entire native population was not to be trusted in a time of war. Film censors cut all of these scenes.

Other scenes adhered to the Navy’s desire for an unvarnished account of the facts, but then it was felt the film went too far in showing all of the ways that the various systems, people, and processes that should have prevented such an attack ultimately failed. These scenes were cut by the censors too. The film that eventually came out was just 34 minutes in length. Despite all this, the film was awarded the Academy Award for Best Documentary, Short Subjects, in 1944.

But even after those cuts, it still included this scene, with veteran actor Joseph Lowery (Drums Along the Mohawk, 1939) playing the part of Pvt. Lockard:

It’s important to note that this film was released in the middle of World War II. Depicting events faithfully was the assignment, but an accurate portrayal of cutting-edge technology of the day such as the SCR-270B was unthinkable at a time when combatants were all racing to have the best long-range aircraft detection systems. So the lack of accuracy in the equipment Lockard is seen using is entirely reasonable. The utter and complete omission of George Elliott is not.

Former Hollywood Mogul Darryl Zanuck Makes His Own Pearl Harbor Movie

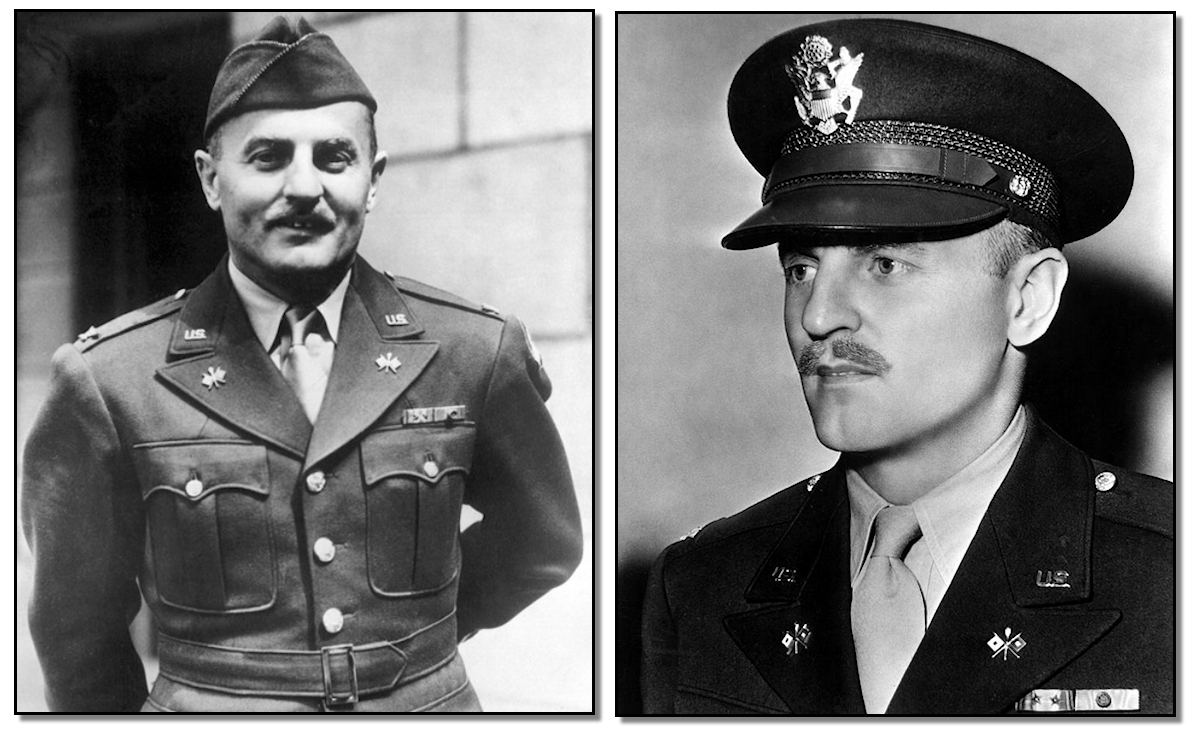

On October 8, 1941, Lt. Col. Darryl F. Zanuck of the U.S. Army Signal Corps visited the Training Film Production Laboratory at Fort Monmouth for the first (and quite possibly only) time. While there, he discussed challenges in producing training films with Lt. Col. Melvin E. Gillette, who was in charge of the unit.

Zanuck (September 5, 1902 – December 22, 1979), at the time vice president in charge of production for Twentieth Century-Fox, was one of the most powerful men in Hollywood. Over the course of his career, he produced three movies honored as best picture at the Academy Awards, but was responsible for many more. Well before Pearl Harbor, believing war to be inevitable, Zanuck resigned his position to focus on serving his country in the Army.

Like many other professionals of the movie production world, his value to the military was seen in helping with films of all sorts, training films, newsreels, war bond promotion, recruiting, etc., the military was heavily vested in the use of film for all sorts of purposes at this time.

Zanuck, a veteran of World War I, was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the Signal Corps. After the U.S. entered the war, he tried to convince all of his top production staff to join him in a special Hollywood film unit dedicated to the Army war effort. He was assigned to the Astoria Studios in Queens, New York, which was being used for various forms of normal Army film production. He did not consider the assignment to be a serious contribution. He chafed at serving alongside people such as Carl Laemmle Jr., the spoiled son of Universal Studio’s founder, who was chauffeured by limousine to Astoria each morning from a luxury Manhattan hotel.

Appalled by such privileged cosseting, Zanuck went down to Washington, D.C. to demand a new and more important assignment. On the way, he made his visit to Fort Monmouth to see the Training Film Production Laboratory. While there, he discussed challenges in producing training films with Lt. Col. Melvin E. Gillette, who was in charge of the unit. As far as is known, it was his only visit to Fort Monmouth.

When he arrived at the War Department, he demanded a riskier assignment from Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall. Since American forces were not yet fighting anywhere, Marshall had Zanuck posted to London as chief U.S. liaison officer to the British Army film unit, where he would be studying army training and recruiting films while under Nazi bombardment by Hitler’s Luftwaffe in the still-ongoing Blitz. Zanuck cheerfully endured the bombs, refusing to leave his room at Claridge’s for its air-raid shelter during nightly raids and instead hosting “blitz parties” because he had such a splendid view of anti-aircraft fire from his hotel room.

He later served as supervisor for Signal Corps training films and the photographic record of the North Africa invasion, for which he was awarded the Legion of Merit. While there, he encountered his old collaborator and nemesis, John Ford, who was attached to the U.S. Navy’s film division.

Zanuck had worked with John Ford on several major projects, but despite their collaboration on The Grapes of Wrath and other successful films, the two were considered adversaries.

Ford had been making films as a commander in the Navy even before the U.S. entered the war, and he was horrified to discover himself drafted into Zanuck’s Africa unit. “Can’t I ever get away from you?” he is said to have growled. “I bet if I die and go to heaven, you’ll be waiting for me under a sign reading ‘Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck’.” They clashed over their roles during the war, and eventually Zanuck resigned, and returned to his Hollywood career.

Darryl F. Zanuck’s Pearl Harbor Movie: – Tora! Tora! Tora!

Two decades after his time in the Signal Corps, Zanuck produced a landmark blockbuster film about the D-Day invasions called The Longest Day (1962), which won critical acclaim and box office success. This would inspire him to create a similar take on Pearl Harbor, the movie Tora! Tora! Tora!, for which Zanuck served as an uncredited executive producer. While his name does not appear in the credits, Zanuck biographers agree that his last movie was a labor of love into which he poured himself, sweating over all the details. Tora! Tora! Tora! was poorly received by critics and audiences alike, although it went on to achieve cult classic status for its adherence to reality, including using only real Japanese actors, directors and producers to tell that side of the story. The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning for Best Special Effects in 1971.

While John Ford’s December 7th, 1941 has only the one scene relating to radar, again, in all likelihood for very good reasons of wartime security, Tora! Tora! Tora! has numerous scenes that show how the new Army aircraft detection technology was rolled out on Oahu, and how the SCR-270B looked when in transit mode, as well as when fully assembled and used by Pvts. Lockard and Elliott. This depiction of what happened in the hour before the attacks tells a completely different story than John Ford’s version:

The starkest difference is that in this version, it’s Elliott who spots the planes, insists on making the call, places the one and only call, while Lockard is passive and somewhat uninterested. This movie clearly positions George Elliott as the hero of this situation, and not Lockard. But it is inaccurate in several regards. In this telling, the two privates see the incoming planes, immediately call it in, are told not to worry about it, and so they shut the system down and headed back to base. In fact, we know that Lockard and Elliott stayed at their station until the radar signals finally disappeared some 40 minutes later.

How do we account for such dramatic differences in two films supposedly dedicated to the facts?

The screenplay for Tora! Tora! Tora! was based on the serialized book by the same name (and another book that focused on the events in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere, relating to the attacks). The book version of Tora! Tora! Tora! relied heavily on government documents and testimony from the various Congressional hearings that were held on this subject.

Such as the one George Elliott showed up for, by surprise, at the last minute.

So it’s possible that the film merely reflects facts that came to light well after John Ford’s movie was released.

As a matter of pure speculation, the question also arises as to what sort of motivations Darryl Zanuck might have had to differentiate his movie about Pearl Harbor from that produced by his nemesis, John Ford. As a former officer in the Signal Corps, perhaps Zanuck wanted to see the role of the Signal Corps men involved in Pearl Harbor told in more detail, and with a very different take on what actually happened. What is clear is Tora! Tora! Tora! was very much Zanuck’s film and there is nothing in it he did not want.

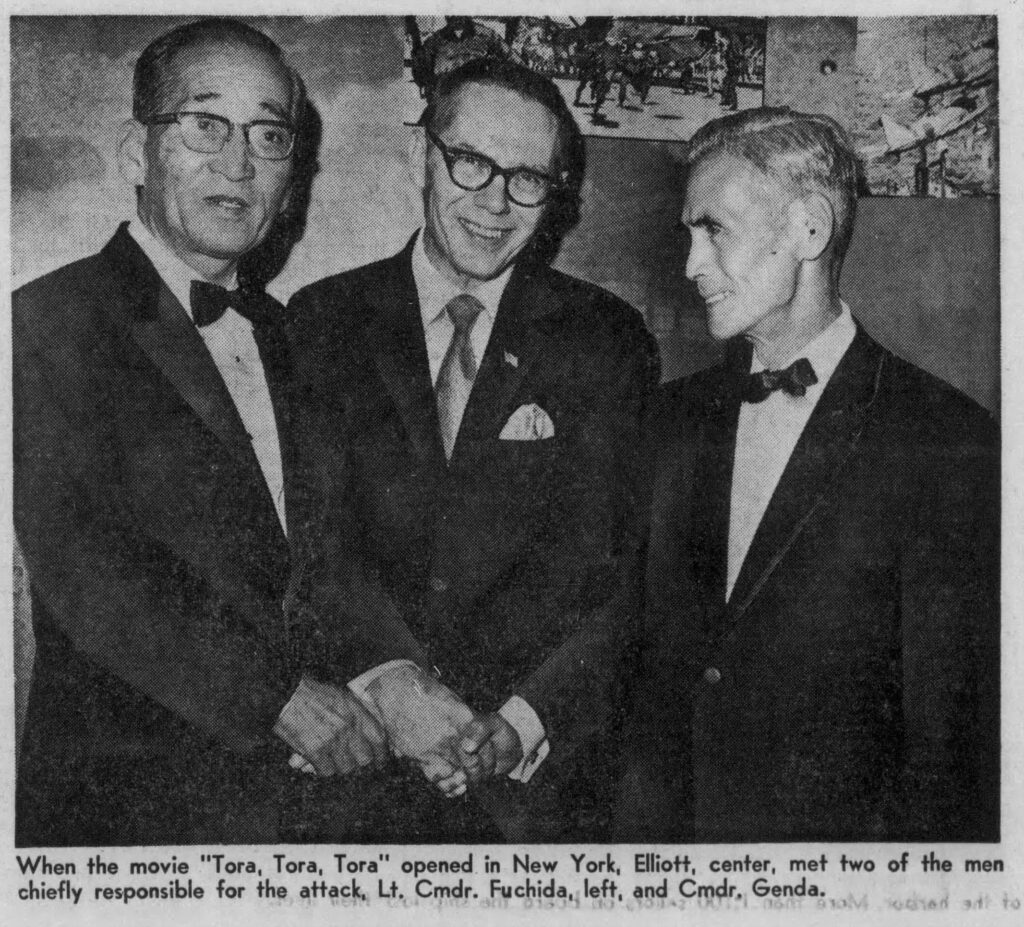

But there is another possibility. George E. Elliott Jr. served as an uncredited technical advisor for Tora! Tora! Tora! So when it was time to portray what happened that day on Opana Point, there was only one voice being heard, and Joe Lockard was nowhere to be found. Elliott even made a celebrity appearance at the New York City premiere of Tora! Tora! Tora!, where he posed for photos alongside the men who orchestrated the Japanese attack in 1941. It is not known how movie producers knew of Elliott, or how to find him, or how he ended up involved in the film.

Aftermath and Legacy

George Elliott retired to Florida and died December 20, 2003. Joe Lockard retired in 1956 and died on November 2, 2012. There is one published report that indicated that Elliott and Lockard were to appear together on a panel in Hawai’i as part of the 50th anniversary events in 1991, but there is no record either way that this occurred. Otherwise, there is no evidence that the two men ever saw one another or spoke again. Whether or not there was any enmity, jealousy, or resentment on the part of Elliott against Lockard is not known; there are numerous stories about the inequities of military recognition and there are any number of reasons why Lockard received all the credit initially, but it can simply just be another Army SNAFU. Today, most accounts of those first minutes of the Pearl Harbor attacks fairly credit Lockard and Elliott jointly. In his 1991 interview for The History Channel, Lockard’s telling of the story is mostly a story of what “we” did, he neither takes any individual credit for himself, but neither does he offer any for George Elliott.

There are lot of “what if” questions regarding the timing of the detection of the incoming Japanese attack and what might have happened if the warning had been heeded.

The radar sites in Hawai’i at that time operated for only three hours per day, from 4:00 – 7:00 a.m., and in the peacetime Army in Hawai’i, after 7:00 a.m. the sites were unmanned. If the Japanese first wave made its initial takeoff just ten minutes later than they did, they would have escaped detection as Lockard and Elli0tt would have shut the system down and taken the shuttle truck back to base before the attackers came within radar range.

If the first wave had made its initial takeoff just ten minutes earlier than they did, Elliott and Lockard would have seen the massive blip while the Information Center was still fully staffed with experienced system operators, and it’s possible that the warning might have been taken seriously, and an alarm sounded.

As it happened, the attackers were noticed just after 7:00 a.m., and the assault began at 7:48 a.m., so we can consider what could have been accomplished by the U.S. military forces given a 45-minute alert. It’s important to remember that this was a peacetime Sunday at a military installation thousands of miles away from where hostilities were breaking out around the world. Even if the Information Center sent out a full-scale alarm at 7:05, how long would it have taken for this to get to the ships in the harbor, and the defenders at the airfields?

But the crews of Navy warships train incessantly on rapid deployment to battle stations when that call goes out, and so if the defenders had even had just 15 minutes of earnest time to prepare for an attack, it seems almost certain that guns would have been manned and ready, instead of the gunners asleep below decks when the first bombs hit. At least some of the fighter airplanes would have made it into the air to put up more of a fight. More soldiers and sailors would have been in action rather than caught by surprise. It seems almost certain that even with a narrow window of opportunity, the Americans could have given the Japanese more of a fight.

However, it is also important to remember that the Japanese had planned three waves of attacks, but called off the third when pilots returning from the second wave reported there were no more viable targets left to attack. If the radar warning had enabled the Americans to mount a more effective defense, in all likelihood that would have triggered the third wave of attacking Japanese planes. At that time, it was still believed that the defenses aboard dreadnought battleships like the USS Arizona were more than up to the task of defending against enemy aircraft, but Pearl Harbor disproved that notion entirely and permanently. The American aircraft carriers, which, given advance warning, would have been able to make a significant contribution to the defense of Pearl Harbor, were out in the Pacific Ocean, on maneuvers, on this day. In this scenario, advance warnings might have effected a more vigorous defense, but in light of a third wave of attacks, without carrier aircraft available for the defense, it’s difficult to imagine a different outcome.

Today, the Opana Radar Site is a National Historic Landmark that commemorates the first operational use of radar by the United States in wartime. It is located off the Kamehameha Highway just inland from the north shore of Oahu, Hawai’i, south of Kawela Bay. Situated within a modern Navy telecommunications station, it is not open to the public. Since the 1941 radar was a mobile unit, there is no physical evidence of the original radar equipment at the site. There is a commemorative plaque on the grounds of the Turtle Bay Resort at the foot of Opana Hill.

Sources:

Darryl Zanuck on Leave; Fox Executive to Devote Full Time to Army Duties. (1942). The New York Times, New York, N.Y., September 1, 1942, P. 23.

Duncan, R. L. (1942). Recommendation for award of Distinguished Service Medal. Headquarters, Signal Aircraft Warning Regiment, Honolulu, Hawai’i, February 1, 1942.

Duncan, Rudolph L. (1942). Recommendation for Letter of Commendation and Selection for Officer’s Candidate School. Headquarters, Signal Aircraft Warning Regiment, Honolulu, Hawai’i, March 24, 1942.

Elliott Relives ‘Tora, Tora, Tora’. (1970). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 27, 1970, P. 61.

George Elliott, 85; Warning on Pearl Harbor Went Unheeded. (2003). The Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, Calif., December 26, 2003, Part A, P. 2. Available: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-dec-26-me-elliott26-story.html.

George Elliott Jr., Radar Operator, Dead at 85. (2003). Associated Press, in the Honolulu Advertiser, Honolulu, Hawai’i, December 24, 2003. Available: http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2003/Dec/24/ln/ln44a.html

Gussow, Mel. (1971). Don’t Say Yes Until I Finish Talking. Doubleday & Company, Garden City, N.Y.

Hearings Before the Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack. (1946). Seventy-Ninth Congress of the United States. United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1946.

Klaus, Mary. (2012). Remembering: Joseph Lockard, Was in the Army During Pearl Harbor Attack. The Patriot-News, Harrisburg, Pa., December 7, 2012, updated January 5, 2019. Available: https://www.pennlive.com/midstate/2012/12/remembering_joseph_lockard_was.html

Lt. Col. Darryl Zanuck Visits Film Lab Here. (1941). Fort Monmouth Signal, Published weekly for the officers and men of Fort Monmouth by the Daily Record, Long Branch, N.J., October 8, 1941, P. 8.

Lockard, Joseph. (1991). The SCR-270-B on Oahu, Hawai’i: Reminiscences. EEE AES Systems Magazine, New York, N.Y., December 1991, P. 8.

Lord, Walter. (2012). Day of Infamy: The Bombing of Pearl Harbor. Wordsworth Military Library, Ware, Hertfordshire, England.

McDonald, George. (2024). Email correspondence with the author, November 19, 2024.

Mosley, Leonard. (1984). Zanuck: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood’s Last Tycoon. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, Mass.

Pearl Harbor – PVT Joseph Lockard. Notable Signaleers. Office of the Chief of Signal, U.S. Army Signal School. Available: https://cybercoe.army.mil/SIGNALSCH/OCOS/HISTORY/whoswho_notables.html

Prange, Gordon W. (1969). At Dawn We Slept. Penguin Books, New York, N.Y., 1969.

Price, Ed. (2003). George E. Elliott, Jr., Army Radar Operator who Warned in Vain of Pearl Harbor Attack. Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 22, 2003, P. 15.

Sadovi, Carlos. (1991). Big Blip on Radar Heralded Air Attack. Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 7, 1991, P. 4.

U.S. War Department Report of Army Pearl Harbor Board. (1944). July 12, 1944. Available: Google Books.

Photo of SCR-270 radar installation. National Park Service photograph, Public Domain. Unknown author. Available: https://www.nps.gov/valr/learn/historyculture/opana-mobile-radar-site.htm

Official U.S. Army photo of Joseph Lockard. Image courtesy U.S. Army Signal Corps Archives, public domain.

Official U.S. Army photo of George E. Elliott, Jr. Image courtesy U.S. Army Signal Corps Archives, public domain.

The story continues beyond George Elliott and Joseph Lockard. When George Elliott called into the Shafter Information Center he spoke with Pvt Joseph McDonald. McDonald relayed the warning to Lt Tyler who he found when timing the message. Tyler said it was nothing.

My father called Back to the Opana site reaching Joe Lockard. Lockard was excited the screen was full ! Pvt McDonald again approached the duty officer stating that he has never experienced anything like this. He requested that they should contact Wheeler Field for intercept and call back the plotters to track the flight.Tyler was unmoved as my father asked him to talk directly to Opana. He heard Well Don’t worry about it as Tyler replied to Lockard.

After the call McDonald again approached Tyler hoping to get Tyler to respond.

When my dad was relieved at about 7:35 , he returned to his tent waking his tentmate Richard Schimmel to “Shim the Japs are coming “ prior to the attack.