On Monday, August 11, 1924, the legendary escape artist and entertainer Harry Houdini gave what may have been his one and only performance in Monmouth County.

Unless it never happened.

It’s entirely possible that, despite our region being home to numerous popular theaters during the age of vaudeville, Harry Houdini never performed here even once.

The image above shows the cover and inside pages of a program for a fundraising event for Monmouth Memorial Hospital, organized by the “Women’s Summer Auxiliary.” Sixth in the parade of entertainment acts presented as “The Inimitable Harry Houdini.”

We know from various sources that Harry Houdini came to Asbury Park on July 17, 1914. Having recently headlined before sold-out audiences across Europe, he was among the most well-known celebrities in the world at the time. He was in one of the entertainment centers of the eastern U.S., during its busiest season. But Houdini did not perform, and his visit went unnoticed. He was only there to visit the hotel room where his mother had died the previous year while he was touring in Europe.

It’s possible that Harry Houdini performed somewhere in our area early in his career, when he was still unknown, but there is no evidence that he did. There were periods when Harry and his wife and performing partner Bess “wandered the northeast” for months, with little record of where they went or what they did. After he became famous, his movements were well-documented, through performance contracts, publicity stunts and news coverage, promotional posters, and Houdini’s diary. Once he became a headliner, much is known about where he appeared. But we still do not know, conclusively, if he ever performed here.

Who was Houdini?

Born Erik Weisz (his father changed the family surname “Weisz” to “Weiss” upon moving to America) in Hungary, Harry Houdini (March 24, 1874 – October 31, 1926) was an American entertainer who became one of the most prominent celebrities in the world. Houdini created the art of escaping from ever-more elaborate and seemingly dangerous constraints, to the amazement of audiences and the disbelief of law-enforcement officers. His extraordinary success spawned numerous imitators, so many that Harry eventually retired from doing escape tricks, and turned his focus to exposing fraudulent spiritualists and bogus clairvoyants. He also appeared in movies, wrote books and experimented with early aircraft among other pursuits.

Harry and his wife Bess lived in New York City for most of their adult lives. He maintained a workshop at 216 19th Street in Union City, N.J., where Harry developed his tricks and stunt props. Over the years, Houdini performed numerous times in New Jersey. He performed in Newark in 1897. He appeared at the Trent Theatre in Trenton from February 19 – 26, 1912. In 1915, Houdini performed in Atlantic City, “shackled and sealed in a wooden box bound with metal and ropes,” submerged in 20 feet of water. Houdini reappeared on the beach within two minutes. He came back to Atlantic City in the latter part of his career when he was exposing fraudulent soothsayers. According to John Cox, creator of the website Wild About Harry, a compendium of 40 years’ worth of Houdini research and stories, Harry Houdini also performed in Paterson, Hoboken, Elizabeth, Ridgewood, Camp Dix and – maybe – Wanamassa.

On November 14, 1922, Houdini was “principal speaker” at “the first open debate and general newspaper interview to be radiographed, in its entirety,” at the WOR broadcasting studios in Newark. The event focused on Houdini’s efforts to expose phony spiritualists and “mediumistic frauds.” Newspaper reporters were invited to attend and ask questions.

And then, in 1924, Harry shows up in a printed program for a hospital fundraiser in Monmouth County. The photo evidence would seem to make this conclusive, but consider the following:

- There is not one word of news coverage of this event anywhere.

- It’s unusual for a major fundraising event to be held on a Monday night.

- Three days earlier, on Friday, August 8, a more typical night for holding a fundraiser, another local hospital held its donor event at the Ross-Fenton Farm. This event received copious news coverage, starting days beforehand and going into great detail afterward.

- In 1922 and 1926, the “Women’s Summer Auxiliary” shows up in press reports planning fundraising events for MMH. The Auxiliary is not mentioned at all, anywhere, in 1924.

- The program also lists The London Steppers as performers. On the same date that this fundraising event was to have taken place, August 11, The London Steppers were advertised to be featured attractions on the opening day of the new vaudeville season at the Majestic Theater in Harrisburg, Pa., 175 miles away. It’s difficult to believe they performed at both venues on the same night.

- In the lower right-hand margin of the inside pages, you can see hand-written pencil marks. This does not appear to be doodling, but it could well indicate that this document was a printer’s proof, and the pencil writing represents client edits, changes. Going to the expense of having a printer render a program is usually something that only happens when everything is confirmed and moving forward.

Whether or not Harry Houdini performed in Monmouth County is a question that we will continue to investigate. But while Harry himself may not have brought his headline act to our area, many others did bring a Houdini show to our shores, in one form or another.

So Many Houdinis

Houdini’s success inspired many others to become escape artists, and some of them did perform in our area. In 1909, The Main St. Theatre in Asbury Park advertised the appearance of “Hilda, The handcuff queen and only rival to Houdini,” noting that “Tonight, Hilda will attempt to make good her wager to free herself from the straight-jacket, at the last performance tonight” (see image above). In 1923, James Farrell of New York City came to Asbury Park billed as “The Second Houdini.” In 1925, Lionel Hirsch, “artist of optical illusions” and a “protege of Harry Houdini” performed in and around Asbury Park at venues such as the weekly lunch meeting of the Lion’s club at the Marlboro Hotel, performing tricks including “The Disappearing Live Horse in Midair.” Armour and Lamott Lewis were local handcuff artists who “have no superiors in their line,” while James Garfield Applegate of Belmar was said to be a rival of Brindamour, the escape artist thought by some to be Houdini’s superior. Brindamour himself performed in Asbury Park as well as at the Opera House in Freehold.

By far, though, the most notable and successful of the “other Houdinis” were Harry’s wife and his brother.

Early in his career, while still an unknown, Harry had partnered with his brother, Theodore “Dash” Weiss, who went by the stage name “Hardeen,” calling themselves “The Houdinis.” Later, Harry met his future wife Bess, and she replaced Hardeen in the act. Both Bess and Hardeen were very accomplished entertainers in their own right. Bess and Harry teamed up on numerous complex magic tricks, mind-reading exhibitions, and illusions including their famous “Metamorphosis” show-stopper. Hardeen was the first magician to escape from a straitjacket in full view of the audience, rather than from behind a curtain, and founded the Magician’s Guild.

A Tragedy Brings Harry Houdini to Monmouth County

In July of 1913, while Harry Houdini was performing in Europe, Hardeen accepted an engagement in Asbury Park. Cecelia Weiss, Harry and Theo’s mother, came along to enjoy the sea air. The show opened at the year-old Lyric Theater at 214 Cookman Avenue on July 14, 1913. Hardeen did Harry’s usual act: escaping from a straitjacket, accepting handcuff challenges from the audience, and closing with the “Milk Can Escape.” On July 15, he leapt, manacled, from the Asbury Park Fishing Pier, and in minutes emerged on shore unscathed. The following day Hardeen escaped from a packing crate made as a challenge for him by The Tusting Piano Company of Asbury Park.

He was off to a fantastic start. Then, after just three days, on July 17, the Lyric ran a special advertisement in the Asbury Park Press announcing a new act to replace Hardeen, with the following explanation: “Owing to the Sudden Death of HARDEEN’S MOTHER His Act Has Been Withdrawn.”

Upon their arrival in Asbury Park, Cecelia Weiss had suffered a stroke. Doctors tended to her in Room 18 at the Imperial Hotel. Hardeen phoned his brother Leopold and sister Gladys who quickly arrived from New York. That night, after escaping from the Tusting packing crate at the Lyric, Hardeen rushed back to Cecelia’s bedside. She struggled to communicate a message, but was unable to speak. She died at 12:15 a.m. on July 17.

Hardeen sent a cable to Houdini in Europe notifying him of their mother’s death. Thinking it was simply a welcoming message from “the folks” back home, he delayed opening it. After performing his Water Torture Cell escape at the Circus Beketow in Copenhagen before an audience that included the royal princes, Harry finally read Hardeen’s cable at a press reception, and fell unconscious to the floor.

On July 17, 1914, the one-year anniversary of Cecelia’s death, Harry, Theodore and Leopold drove back to Asbury Park to visit and photograph Room 18 at the Imperial Hotel. No one knows what happened to those photos, and no one noticed one of the most famous celebrities in the world while he was here.

So, Did Harry Perform Here or Not?

If the Monmouth Memorial Hospital program represents an event that, for whatever reason, did not take place, the question remains, why didn’t Houdini play Monmouth County? Once he became a headline star, he was under contract to major theater chains and played only large cities. Originally from the Midwest, and having performed there early in his career, he was very comfortable touring in the western states.

During those years where little is known of where Harry and Bess went, they might well have come here. In those days, each of the cities in Monmouth County had its own daily newspaper, so the question arises, if they were here, why didn’t Harry walk into a police station and issue his usual handcuff challenge in front of the local press? The presence of rivals such as Brindamour performing here would not likely have dissuaded Houdini, who liked to challenge his pretenders in face-to-face contests to see who was the real “king of handcuffs.”

Houdini’s diary may hold the answer, one way or the other. A few pages of his diary have been photographed, and they show great attention to detail. The owner of the diary, however, has refused to publish it or even make it available to biographers, with rare exceptions. In fact, it is not even known for certain who actually owns Houdini’s diary. It’s possible that this secrecy is out of respect for Houdini’s wish that his secrets would follow him to the grave. For example, in his will, Harry left all his files and schematics to Hardeen with instructions to burn them, which he did.

A year after her husband’s death, Bess Houdini continued performing Harry’s act, hiring other men to play Harry’s part, performing his famous escapes using his techniques and equipment. They performed at the Broadway Theater (later called the Paramount Theatre) in Long Branch on March 5, 1928, and at the St. James Theatre in Asbury Park on March 7. At long last, a real Houdini had come to Monmouth County to put on a show.

Sources:

Advertisement. (1909). Asbury Park Press, November 13, 1909, P. 7.

Brandon, Ruth. (1993). The Life and Many Deaths of Harry Houdini. Random House, Inc., New York, N.Y., 1993.

Christopher, Milbourne. (1969). Houdini: The Untold Story. Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York, N.Y., 1969.

Cox, John. (2016). Death in Asbury Park. Wild About Harry, Tuesday, February 26, 2016. Available: https://www.wildabouthoudini.com/2016/02/death-in-asbury-park.html

Gresham, William Lindsay. (1959). Houdini: The Man who Walked Through Walls. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, N.Y., 1959.

Henning, Doug, & Reynolds, Charles. (1977). Houdini; His Legend and His Magic. The New York Times Book Company, New York, N.Y., 1977.

Jaher, David. (2015). The Witch of Lime Street: Séance, Seduction, and Houdini in the Spirit World. Crown Publishers, New York, N.Y., 2015.

Kalush, William, & Sloman, Larry. (2006). The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero. Atria Books, New York, N.Y., 2006.

Mother Dying, Actor Appears. (1913). The Asbury Park Press, July 17, 1913, P. 4.

Mrs. Harry Houdini Here Tomorrow, Still Refuses To Bare His Secrets. (1928). Asbury Park Press, March 7, 1928, P. 8.

Mrs. Houdini Hits Smoking By Girls. The Daily Record, Long Branch, P. 5.

Posnanski, Joe. (2019). The Life and Afterlife of Harry Houdini. Avid Reader Press, An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc., New York, N.Y., 2019.

Rapaport, Brooke Kamin. (2010). Houdini: Art and Magic. The Jewish Museum, under the auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America; New Haven, Conn., Yale University Press, 2010.

See Disappearing Horse. (1925). Asbury Park Press, July 7, 1925, P. 2.

Silverman, Kenneth. (1986). Houdini!!! The Career of Ehrich Weiss. HarperCollinsPublishers, New York, N.Y., 1986.

Telegraph Tabloids. (1925). Courier-Post, Camden, N.J., July 29, 1915, P. 10.

The Stage. (1910). The Paterson Morning Call, Paterson, N.J., February 4, 1910, P. 12.

To Broadcast Open Debate and Newspaper Interview With Houdini. (1922). The Central

Jersey Home News, New Brunswick, N.J., November 11, 1922, P. 12.

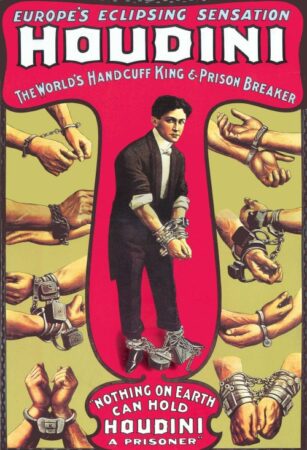

Featured Image: Promotional posters such as these very rarely had copyrights renewed. We believe this to be consistent with Fair Use Doctrine.

The program for the 1924 summer fundraising event for Monmouth Memorial Hospital. Photo credit: John Cox, Wild About Harry, used with permission.

Harry Houdini promotional photograph. Created: circa 1899. McManus-Young Collection – Library of Congress, Public Domain.

Leave a Reply