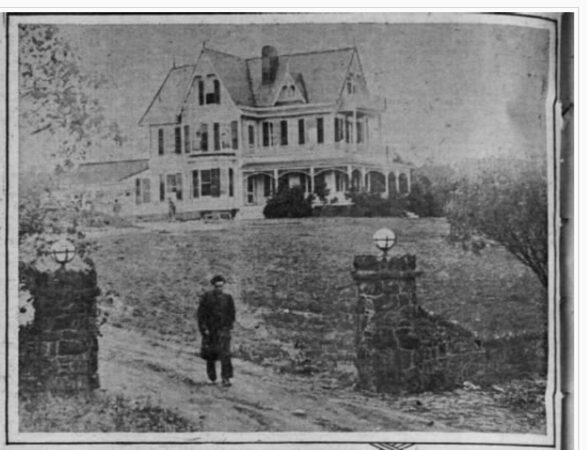

On March 23, 1933, Alexander (Al) Lillien Jr. (born February 28, 1897), a “master liquor-runner,” was found murdered in his Middletown mansion. Lillien, 36, along with his brother William, controlled a bootlegging gang that extended from Montreal down to Virginia, operating out of the Navesink neighborhood near where the navigation tower now stands.

Press reports stated that the house was in Atlantic Highlands. In fact, the house had an Atlantic Highlands postal address, but was located within the municipality of Middletown Township.

Detectives believed that the killers “swept up to the front door in an automobile, rang the bell and killed Lillien when he answered it.” Lillien’s bodyguard and his caretaker had found the body after returning from a business trip, which would explain why Lillien answered the door himself. Lillien was shot three times in the head and neck from behind; observers thought he was likely fleeing toward a balcony in an effort to escape.

According to the Asbury Park Press, “A pair of pall bearers’ gloves and an upturned ace of spades, found on the buffet in the dining room of the palatial home overlooking Sandy Hook and the harbor, was accepted by police as evidence that Lillien had been ‘put on the spot.’” Al Lillien was alone when his murderers made their attack, and there was no evidence that he made any attempt to resist them, although police described him as a man “who would shoot it out with the best of them.”

The Feds Raided Al Lillien’s Mansion in 1929

Several years before Al Lillien was murdered, his home was raided by federal agents. On October 16, 1929, at the height of Prohibition, 130 law enforcement agents raided 35 homes and buildings in New York and New Jersey, including Lakewood, Point Pleasant, West End, Red Bank, Highlands, Atlantic Highlands, and Middletown. The raid included Al Lillien’s isolated house atop the ridge in the Hillside section of Atlantic Highlands, overlooking Sandy Hook Bay.

Before 1920, the house had been owned by the operatic and music hall impresario Oscar Hammerstein Sr. In the house, agents found a powerful shortwave radio, a cellar full of submachine guns, automatic rifles, pistols and ammunition, and 16 men who denied any knowledge of the radio or weapons. Authorities believed the house was the center of a huge bootlegging operation smuggling rum from Canada and the Caribbean.

Authorities had caught on to Lillien’s operations when a government radio inspector scanning the airwaves for unlicensed operators stumbled upon a coded broadcast. Eventually, the code was broken, and revealed that the operators had a clear view of Coast Guard vessels patrolling the area, and were able to steer smuggler ships around them. Lillien’s gang also used radios to direct airplanes to “handle rush orders.”

The house had “bulletproofed walls and a blinker on a bedroom balcony” to signal when it was safe for bootlegger boats to land with their illicit cargo. A six-car garage was equipped with a hydraulic lift that led down two floors to a hidden storage area for stashing cases of booze. Telescopes were found on the third-floor cupola facing the bay and ocean. In the basement, tunnels led to underground vaults beneath a newly constructed tennis court that also featured three large spotlights affixed to the perimeter, used to guide the fleet of motorboats.

The most important piece of evidence found at the mansion was a little black book with records of syndicate transactions, including transportation costs and bribes. From this, prosecutors estimated that Lillien’s gang had taken in more than two million dollars in just six months. The gangsters imported some 10,000 cases of liquor per week, worth up to $35 million per year wholesale.

Lillien was not home at the time of the raid. Sensing the increase in government enforcement efforts in the area, he had fled to Canada, and ordered those who remained in the house to clear out all of the contraband. In 1931, Lillien returned to New Jersey to face charges of conspiracy to violate the national prohibition law; 38 others were also brought to trial.

The Government’s case rested on three facts: the ring operated a fleet of vessels from Canada to the United States; these vessels, directed by radio transmissions, smuggled liquor into the country; and the syndicate maintained seven bank accounts throughout the New York–New Jersey area, containing large sums of money. Yet, little evidence directly connected the alleged conspirators with these crimes. Following a three-week trial in Trenton that was two-and-a-half years in preparation by prosecutors, all defendants were acquitted by a jury that deliberated about seven hours.

An Unsolved Murder

After discovering Lillien’s body, Walter Cerley, Lillien’s bodyguard, and William Feeney, caretaker of the mansion, were held as material witnesses. Early on, authorities held several theories on Lillien’s murder. Initially labeled as a “gigantic and murderous struggle for control of a rum fleet,” they eventually looked to his partners in crime.

Charles Solomon, also known as “Boston Charlie” or “King” Solomon, was a “reputed overlord of vice and liquor rings,” and a partner of Lillien. Two months before Lillien’s killing, Solomon was murdered in his Boston nightclub one day before he was to testify before a grand jury about smuggling. Al Lillien had already given testimony, so some believed that his killing was punishment for revealing too much. Another theory, according to the Asbury Park Press, held that Boston Charlie “allegedly was implicated in the kidnapping of Lillien last summer, a fact which up to now was generally unknown.” Lillien paid $35,000 for his release, and the Press informant said that Solomon might have been “rubbed out” for his part in the kidnapping, and Lillien then killed for his part in Solomon’s murder. Police also said another of Lillien’s partners, who was not named, had been recently slain in Baltimore.

Some have suggested Lillien’s murder was at the behest of notorious mob leaders Albert Anastasia and Meyer Lansky. Others noted that Lillien and his men frequently ran into conflict with Charles “Vannie” Higgins, the bootleg boss of Brooklyn and Long Island, and an associate of Luciano. The end of Prohibition seemed inevitable, and some smugglers began to plan to switch to legitimate operations, which may also have been provocation.

But in the end, the murder of Al Lillien was never solved, and his criminal empire vanished. Lillien is interred at Beth-David Cemetery in Kenilworth, Union County, N.J.

Postscript to the Murder of Al Lillien

On July 22, 1932, Al Lillien, driving a “high powered armored car,” had been involved in a serious accident on Leonardville Road in Middletown as he headed back to his mansion hideout. His victims sued, and on March 31, 1934, a year after Lillien’s death, a jury awarded them $33,040, which turned out to be almost 90 percent of the estate Lillien left behind. Lillien’s wife Beatrice received the rest.

Sources:

Boyd, Paul D. (2004). Atlantic Highlands: From Lenape Camps to Bayside Town. Arcadia Publishing, P. 146-150.

Deitche, Scott M. (2018). Garden State Gangland: The Rise of the Mob in New Jersey. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Md., P. 18.

Joynson, George. (2010). Wicked Monmouth County. The History Press, Charleston, S.C., P. 116.

Linderoth, Matthew R. (2010). Prohibition on the North Jersey Shore: Gangsters on Vacation. The History Press, Charleston, S.C.55r

Mappen, Mark, Saretzky, Gary D., & Osovitz, Eugene. (2013). Prohibition in New Jersey: The Bootlegger Era. Catalog of the Exhibit at Monmouth County Library, Manalapan, N.J., October 2013. Monmouth County Archives, available: https://www.monmouthcountyclerk.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2013-Prohibition_exhibition_-FINAL.pdf

Al Lillien, Shore Rum King, Murdered. (1933). Asbury Park Press, March 24, 1933, P. 1.

Crash Verdict takes $33,040 of Al Lillien’s Estate of $38,119. (1934). Asbury Park Press, March 31, 1934, P. 2.

Conspiracy Seen in Rum Runner’s Slaying by Gang. (1933). Associated Press, in The Daily Messenger (Canandaigua, N.Y.), March 24, 1933, P. 1.

Jury Considering Rum Gang Verdict. (1931). Associated Press, in The Central New Jersey Home News (New Brunswick, N.J.), July 11, 1931, P. 1.

The New York Times (1933). Rum Radio Ring Head Slain in New Jersey. March 24, 1933, P. 88.

Photo of Oscar Hammerstein mansion. Creator, date of creation, publisher and date of publication unknown. Image courtesy Ralph Bitter and Middletown Township Historical Society, used with permission.

My great grandfather was a part of his syndicate. I wish I could learn more.

I am doing research on Prohibition in Monmouth County. Would you be willing to talk to me about your grandfather’s role and your recollections of what you’ve heard about those days?

Snitches get stitches lol

Jkjk kinda