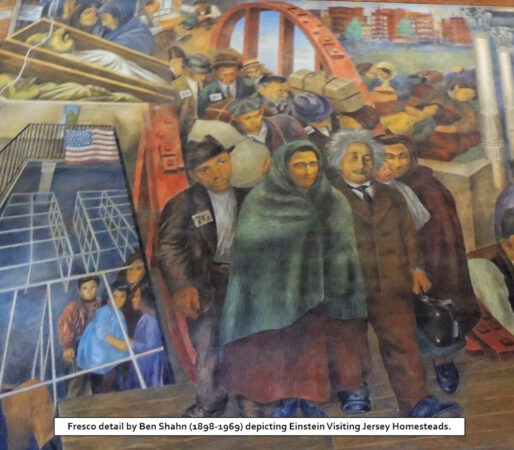

Timeline story by Yvette Florio Lane, Ph.D.

On October 24, 1936, Albert Einstein, arguably the world’s best-known scientist, was among a small group of public intellectuals and social influencers who attended the opening of an experiment in planned communal living in the Garden State, one created “of, by, and for needle workers.”

The project was initiated by the Division of Subsistence Homesteads, a New Deal agency that was intended to relieve industrial workers and struggling farmers from complete dependence on factory or agricultural work. In 1933, during President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration, it was known to contemporaries as Jersey Homesteads. This 1200-acre tract, carved from the municipality of Millstone, five miles from Hightstown, was described as a “rural utopia,” nestled among the “gently rolling hills” of western Monmouth County. Of its 1200 acres, over 500 were to be used for farmland, while the remainder would contain 200 newly built homes on one-and-a-half acre sites, as well as a community school, a factory building, a poultry yard, modern water and sewage plants, and sites that were reserved for future shops and recreational facilities.

As stated in a government publication, “The original objectives of this industrial-agricultural community were to demonstrate the feasibility of decentralizing an industry which for years has been concentrated in congested areas of large cities amidst slum living conditions and sweat shop working conditions; to demonstrate the merits of combining farming with work in a predominantly seasonal industry and one which is subject to the dictates of fashion; to conduct an experiment in co-operative working and living.”

Although eventually more than 100 New Deal communities were created, Jersey Homesteads was the only one to be “settled by a completely homogeneous population with strong religious ties.”

That is, it was settled almost exclusively by migrant Jewish garment workers, most of whom were socialists. More than 1000 applicants sought a place in the homestead; of the 200 applications selected, 150 were families headed by unemployed garment workers, 20 were skilled in agricultural realms, and the balance consisted of various retailers and artisans.

While other collective communities had been previously attempted in the United States, Jersey Homesteads was unique in at least three ways: it was largely a top-down effort in that it had been conceived of and developed under the auspices of a federal program; its members were drawn almost exclusively from the immigrant Jewish community; and it was the only one that aimed to combine rural and urban endeavors in a synergy of agriculture, industrialized manufacturing, and the retail operations central to maintaining a self-sustaining community.

“Surprised, and gratified, and highly pleased”

As a much-honored guest at the events of October 24th, the occasion was not Einstein’s first, nor only visit to Monmouth County, but it was one that made headlines. And it is among only a handful of his travels within central New Jersey that can be reliably documented. The press described him as “an artist’s dream of the eccentric professor… dressed in a well-worn pair of brown oxfords, no socks and no necktie,” and whose “characteristic display of flowing gray locks was unencumbered by chapeau.”

Einstein, a relatively recent United States transplant, was one of New Jersey’s most illustrious residents at the time. He was born in 1879 into a family of secular Jews who left the German Empire for Switzerland when he was 17 years old. As a young man, he began the work in physics that made him a household name and a worldwide celebrity. Following the National Socialist seizure of power in 1933, he left Europe permanently. Later that same year, he accepted a faculty post at the newly created Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey, where he landed with a small family entourage. In 1935, the Einsteins settled at 112 Mercer Street, a nineteenth-century wood frame home near Princeton University.

In addition to the scientific contributions that cemented his legacy, Einstein also lent his name and time to a number of social programs and initiatives, including serving as trustee on the Jersey Homesteads board whose members were to “retain active control and direction of the venture for at least five years until the homesteaders are deemed capable of taking it over themselves.”

Along with his influence and fame, however, Einstein was known to be extremely reluctant to seek the spotlight or to perform for the press. In fact, one of his remarks audible enough to be captured by reporters who followed him on his visit to the Jersey Homesteads was “I don’t like publicity.”

Despite his distaste for the spotlight, he allowed the press to follow his tour of the settlement, of whose creation he had been an early and important supporter. As he examined the garment factory, Einstein spoke individually with many of the community’s recently settled residents, expressing interest in their work materials and processes, as well as in the design and construction of the facility itself. At the day’s key event–the lottery to determine which of the newly completed houses each individual family would occupy–he held the hat from which the community’s children took turns drawing names.

Although Einstein did not give a prepared speech, at the end of the day he did dictate some remarks which were taken down and read aloud to the crowd:

Dr. Einstein says that he will never forget that if it were not for President Roosevelt’s administration, this kind of establishment would never be made possible. He (Einstein) will always be thankful for the opportunity given city workers to enjoy the pleasures of invigorating country life in connection with their pursuits as workers in their field. All of us hope that this example will be taken up by many other workers in the future, and the social progress of this country will thereby be helped thru [sic] the successful achievement of this enterprise.

He also signed the written statement as photographers captured the moment.

Finally, in response to a reporter’s question, he urged people to vote for Roosevelt in the upcoming election, noting that he, not a U.S. citizen, was unable to do so.

In addition to the factory inspection, he also visited the home of Dora Gerber (or Garber), the president of the community Consumers’ Club. There he voiced congratulations to architect Alfred Kastner, the Resettlement Administration designer of the site.

Although he previously had written to Washington, D.C. officials to express his frustration that the project was taking too long to reach fruition, all that seemed to be in the past as he displayed “amazement” at the progress and remarked that he would enjoy having one of Kastner’s modern homes as his own.

The homes themselves are among Jersey Homestead’s lasting marks on the built environment, as most of the original structures remain, although in many instances they have been renovated to adapt to changing needs and tastes of their twenty-first century residents.

Originally made of made of whitewashed cinder block, they were designed by European immigrants, the architects Kastner and Louis Kahn, in the style associated with the German Weimar-era Bauhaus school. In stark contrast to the urban tenement dwellings of New York and northern New Jersey that the applicants had left behind, the new homes were, “modern in every detail,” filled with air, and according to one report, the “amount of light admitted through the windows is impossible to describe.”

It may have been the first time that most of the residents lived in a single-family home. Certainly, it would have been the first time they encountered features that were only beginning to be common aspects of suburban living such as built-in kitchen cabinets and heated indoor plumbing. Especially for members of the industrial working class, in whose homes amenities of modern living were comparatively substandard, these new accommodations were worthy of excitement. It is not surprising that at least one of the women, Mrs. Samuel Imber, exclaimed, as she gestured toward her new home, with its “tiled white bath” and kitchen with “a variety modern contrivances” including gas stove, hot water heater, and a gas refrigerator that “Ach it is wonderful. I haf never been so happy in my life.”

Unfortunately, as grand as the plans were, and as high as were the hopes for a new experiment in living, Jersey Homesteads, as initially envisaged, would fail by 1938. The reasons for the collapse included garment workers’ union opposition, lack of adequate supporting infrastructure, and a combination of other social and political factors. The homes were eventually leased or sold to others who had not been involved in the initial program, the factory closed, and the farm efforts effectively abandoned. Nevertheless, the community, later renamed in honor of Franklin Roosevelt, continued, and in fact, in some ways has thrived, as an artists’ enclave, well into the twenty-first century.

Yvette Florio Lane holds a PhD in history from Rutgers University. She writes about work, advertising, and gender, among other topics of social and cultural history. Her recent book, Shrimp: A Global History (Chicago University Press) was published in 2019.

Sources:

Jersey Homesteads, New Jersey. (1940). United States Farm Security Administration, Farm Security Administration Collection, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1940. Available: https://archive.org/details/jerseyhomesteads00unit/page/n11/mode/2up

Einstein Likes Jersey Project. (1936). Asbury Park Evening Press, Asbury Park, N.J., 24 October 1936. P. 1.

Ingham, Van Wie. (1935). Jersey Homesteads Expected to Become Utopia. The Sunday Times, New Brunswick, N.J., July 7, 1935, P. 1.

Einstein Visitor at Homesteads. (1935). Daily Home News, New Brunswick, N.J., October 24, 1936, P. 2.

Williams, Beryl. (1936). Jersey Homesteaders Near Hightstown Have Rush of Orders. The Sunday Times, New Brunswick, N.J., July 26, 1936, P. 1.

Hightstown Progress. (1936). The Sunday Times, New Brunswick, N.J., April 1936.

Leave a Reply