In early 1917, Thomas Alva Edison fell ill, and so his Naval Consulting Board moved on without him to recruit a scientific advisory group and build a new naval research laboratory. After he recovered, U.S. Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels suggested that Edison forget about board responsibilities and return to inventing on behalf of the navy. Daniels offered to provide support by funding a 25-man team to be chosen by Edison.

Still keen to contribute his talents to the war effort, Commodore Edison focused his experiments on submarine detection. He initially set up operations atop Eagle Rock, overlooking West Orange, with a 40-mile visibility range. In early spring of 1917, however, Edison was moving on from those mostly futile experiments, and wanted sea access, and so set up shop on Sandy Hook. Edison finally had his Sandy Hook Naval research facility, minus interference from government types.

The team had only had time to erect a small shack on a pier south of Fort Hancock when President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany on April 6, specifically citing the ongoing U-boat carnage being wrought on American vessels. Spurred by this new urgency, Edison threw himself into a spate of new experiments. He brought four scientists from Princeton to advise him on “trajectory graphics, radio resonance, air and sea navigation, and gyroscopics.”

During this time he invented a number of devices, including an airplane direction finder, a depth charge that took its own “soundings,” and a waterproof microphone that he developed into an underwater listening system that allowed ships to hear the engine of a submarine more than a mile away. Over the next 18 months, Edison and his team invented 39 new defense devices, systems, strategies, and tactics. These included everything from a wireless telegraph message scrambler, nocturnal telescope, anti-torpedo cannon-fired steel mesh “drapes,” underwater coastal surveillance stations, a grease for rustproofing submarine guns, and even a water brake to enhance quick ship turns.

In a stark departure from his normal self-publicizing tendencies, Edison conducted his naval defense experiments in total secrecy. He worked 24-hour days, often financing experiments out of his own pocket, and urging his recruits to work pro bono.

Edison needed a large research vessel for his waterborne experiments and was disappointed at the boats initially offered by the navy. On July 18, 1917, a Red Bank newspaper observed that Edison was conducting his experiments aboard the “gasoline cruiser Rampart,” which had been running back and forth from Red Bank to Sandy Hook over “the past several months.” Prior to the Rampart, Edison hired Andrew White’s motor schooner Olivia B, built in 1912, to conduct his experiments. “Few Red Bankers recognized the great inventor while he was here. He ate his meals at the Globe Hotel and stopped at Capt. Irwin’s boat works for a brief talk with Mr. Irwin,” whom he had known for twenty years.

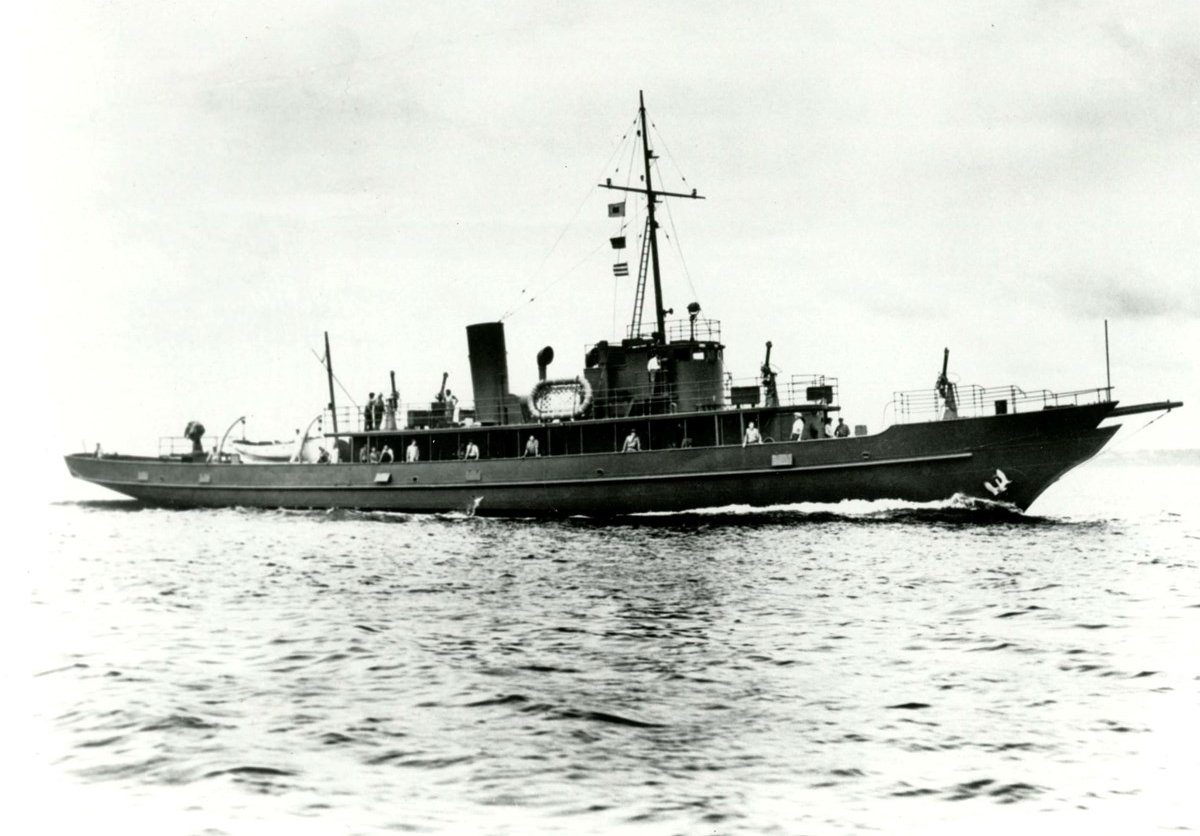

After complaining that these vessels were insufficient, the Commodore was given the USS Sachem (SP-92), the “SP” standing for “Section Patrol.” USS Sachem was a 210-foot navy submarine chaser, outfitted with a crew of 20, to serve as his floating laboratory. His work continued, aided by his wife Mina, who helped bridge Edison’s deafness so he could communicate with his team. Having a woman aboard a U.S. Navy vessel was highly unusual at the time, such ships not being properly equipped for female passengers, but once again Edison insisted, and Daniels paved the way for the Sachem to set sail with both Mr. and Mrs. Edison aboard.

Throughout this time, Edison had been submitting his inventions to the Navy Secretary Daniels, convinced they were working, operational devices ready to be deployed. But they all went nowhere. He received rejections that were “respectful and exhaustively argued,” but Edison considered this to be a bias on the part of the defense community against civilians. He handed over the Sachem experiments to his staff and headed to Washington to lobby on behalf of his submissions. He ended up getting sidetracked in an analysis of U-boat ship sinkings, arriving at a series of recommendations for systems and tactics that he believed would significantly enhance ship survival rates. Again, his ideas were not implemented, to his enormous frustration. In early February of 1918, after several months in Washington, Edison and Mina moved to Key West, and had the Sachem join them at the Key West Naval Station.

Edison continued his experiments in Key West, but in the end, the armed services would fail to accept a single one of the 45 or so inventions he ended up submitting. For a man of Edison’s wholly unprecedented achievements, this was a stinging rebuke which would fester and chafe at the great inventor for the rest of his life. Edison turned down a medal for his defense work, arguing that he deserved it no more than any other member of the Naval Consulting Board.

Sources:

Morris, Edmund. (2019). Edison. Random House, New York, N.Y.

Baldwin, Neil. (1995). Edison: Inventing the Century. Hyperion, New York, N.Y.

Edison May Quit Naval Board. (1917). The Daily Record, Long Branch, N.J., March 7, 1917, P. 1.

Thomas A. Edison Here. (1917). The Daily Register (Red Bank), July 18, 1917, P. 1.

Asbury Park Press. (1947). April 23, 1947, P. 7.

Image credit: National Parks Service. Available: https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/historyculture/thomas-edison-in-world-war-i.htm?no-ist

I don’t have a comment but I do have a letter from Thomas Edison dated May 7, 1917. I have had this letter for many years trying to do research on what he was working on at the time. Thomas Edison had a letter written to Mr. Walton Clark of Philadelphia decline his dinner engagement as he was working with the Experiments with the government. this letter is signed by Thomas a Edison with his stationary watermark. I would like to learn more of his works at this period of time if there’s anyway possible you could help me greatly appreciate.thank you Robert Johnson.

Hi Mr. Johnson, that is a fascinating time in Edison’s career that’s been largely overlooked by historians because it was one of the few times in his great career that he utterly failed. Much of what we’ve learned about what he was doing in 1917 has only come to light in recent years through the work of the people at the Thomas A. Edison Papers project at Rutgers University. I’m sure they would be interested in seeing your document, and you can search their archives for more about that year: https://edison.rutgers.edu/research/digital-edition. I just did a search for “Sachem,” the name of the ship Edison was given to use for his research in Raritan Bay, and there are new records that have emerged including some accounts from Edison’s wife about her experiences aboard the research ship.

I have a copy of a letter on Edison’s letterhead in which he withdraws his support for the Naval Research Laboratory reasserting his position that if the lab was located in Washington DC and staffed by Naval Officers it would be nothing more than “a sinkhole for money.” Can you comment on the authenticity of the exchange?

Biographer Edmund Morris wrote that on March 7, 1917, Edison sent a letter to the Secretary of the U.S. Navy and said he would quit the Naval Consulting Board that he had conceived, created, and chaired, if his proposed new research laboratory was built anywhere other than Sandy Hook. That biography did not include the full text of that letter, so I cannot confirm that the sinkhole phrase is a part of that text. The people at the Edison Papers project at Rutgers could certainly confirm this for you.