By John R. Barrows

On June 2, 1953, Servais LeRoy died in Keansburg, and was buried in Middletown. Few people took notice, the old man had long become just another retiree living along the Raritan Bayshore. Even his neighbors didn’t know that at one time, he was among the world’s most famous and accomplished magicians, during the Golden Age of Magic.

Between the 1850s and the 1930s, the world was transfixed by a proliferation of staged illusions purporting to be supernatural wonders, mystifying tricks, or death-defying escapades. In a word: magic! Theaters specializing in magic acts flourished during these years, and elaborate shows toured the world, each promising something more exciting and special than the last.

The dawn of the 20th century was a period of great scientific advancement, but at the same time, there were still a great many unknown and mysterious things in the world, and people were willing to believe the feats performed before their very eyes, even if they were manifestly quite beyond belief.

In what became known as the Golden Age of Magic, magicians were among the world’s most famous celebrities. Such luminaries as Blackstone, Kellar, Thurston, and, of course, the Great Houdini, were household names and celebrated figures at the grandest theaters, houses of aristocracy, and courts of royalty around the world. These familiar names were just some of the many entertainers who toured the world as stars of the emerging genre. Some of the lesser-known men and women in the field were often the ones responsible for actually inventing the illusions and tricks that were purchased – or copied – and subsequently performed by their more successful colleagues.

In addition to their live performances, some magicians earned money by publishing books about magic, writing plays that revolved around magic acts, staging private magic demonstrations for wealthy patrons, and selling magic tricks and instructions to amateurs and aspiring professionals alike. For the best of the best, magic could be a lucrative business.

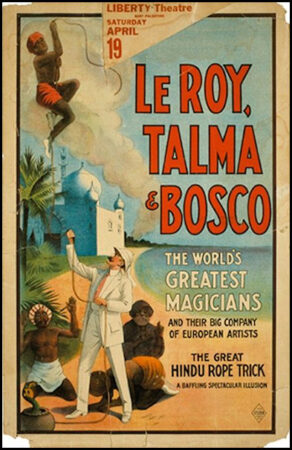

If you were a fan of magic during its heyday, you were almost certainly familiar with the great Servais LeRoy, the diminutive Belgian who many credit with inventing the famous “levitating lady” illusion that is still used by magicians today. LeRoy performed with his wife, who was known as “Talma,” and a third magician, intended to be a comic foil, who was known as “Bosco.” Together, they were promoted as the “Monarchs of Magic,” as “Le Roi” in French translates as “the king.”

Over the years, “LeRoy, Talma and Bosco” performed at the great theaters of Europe and the United States. All told, some seven different men played the role of Bosco, but there was only one Servais LeRoy, and only one Talma.

And after shuttling back and forth between New York City and London for many years, they all finally settled down for good, in Keansburg, in Monmouth County.

Servais LeRoy

Jean Henry Servais LeRoy was born in Spa, Belgium, on May 4, 1865. His grave marker says he was born May 4, and in 1943, the local Keansburg newspaper noted that he would be celebrating his birthday on May 4. In his own memoirs, LeRoy said he was born on May 2, but this may be the product of a faulty memory. LeRoy wrote his memoirs late in life and many details he sets forth do not agree with other accounts of his life. The question of his birthdate is just one example.

Born to a Belgian father and an English mother, he left home at age 12 (according to his memoirs, he was 10) and went to London, where he was “adopted by a Civil Service employee of good position” and lived and went to school in Plymouth. Later, while in Wales pursuing a career in soccer, LeRoy saw a man perform the “Cups and Balls” trick. He was hooked. He practiced that trick until he could fool the man whom he had first seen perform it. He picked up card and coin tricks from books, and soon LeRoy had a modest magic act he performed for friends.

Living in London, where many magicians were based or appeared while touring, LeRoy immersed himself, spending hours in magic shops and meeting other men of magic. He was eventually invited to join an elite group of magicians who met every Sunday evening to discuss all things magic. From these people he learned of the various styles and ways of presenting illusions, as well as what worked with which audiences, and what failed. For example, western audiences still had a sense of fascination with the Far East, and several white magicians performed as “Chinese” acts, in costumes and yellowface, because audiences were more apt to believe that such magic was possible in faraway parts of the world. For example, Arthur W. Hartopp was a professional illusionist who performed under the name Li Sing Foo among other exotic aliases.

When LeRoy was 25, still considering himself to be a “mere boy,” he and a few other aspiring conjurers embarked on a series of performances in Spain that enjoyed a small measure of success but were not particularly lucrative. Shrewdly, the group used this as the basis to return to England from what they promoted as a triumphant standing-room-only tour of Europe.

LeRoy was hired to open at the Royal Aquarium in Westminster, London, where he soon achieved noteworthy success. It was here that he met a striking 16-year-old vocalist named Mary Ann Ford, who would become his performing partner, and later, his wife. He gave her the stage name of “Mercedes Talma,” but like many magicians, she went by just one name, Talma.

Servais taught Talma to perform coin tricks and she had a knack for sleight-of-hand, and soon gained fame as the “Queen of Coins.” Harry Houdini said that Talma was “without a doubt, the greatest sleight-of-hand performer that ever lived.” Talma toured as a star in her own right for a number of years, as palmistry acts were very popular at the time. Talma boasted that she could hold 30 coins in her small hands, and she also had a trick involving silks and flags that kept coming out of a tambourine until the stage was covered in fabric, after which rabbits and ducks would then emerge, to the delight of audiences.

A promoter brought LeRoy to the U.S., where he debuted what he called his “Doubling Illusion,” also called the “Flying Visit,” which he claimed was the first “doubling illusion” in the world of magic. The secret? LeRoy was the first magician to use doubles in his illusions. His brother Charles LeRoy served as his double, while Talma’s sister Elizabeth Ford served as her double.

LeRoy was offered the chance to be part of an act in which three magicians toured on the same bill. At first, the act was simply a sequence of one magician performing, followed by the second, and then the third. One of the others specialized in a comedy magic act. It was LeRoy who had the idea to have all three on stage at the same time, performing various tricks and illusions. This new and very different approach to presenting magic was performed for the first time at Waldmann’s Theatre in Newark, New Jersey. The act was an “instant success.” The three men realized that this new way of staging magic shows, with multiple magicians performing at once, was the way to go. They also agreed they all wanted to team up with others, and so the act that was promoted as “The Great Triple Alliance” was dissolved, although LeRoy would promote his next act using that appellation again.

LeRoy went back to England where he again performed with Talma. To add the third person to the act, he recruited Leon Bosco, a portly bald man who was performing comedy on vaudeville stages. In what they called their “Big Show,” LeRoy performed major illusions in the center of the stage while Talma performed sleight-of-hand coin and card tricks out among the audience; Bosco acted as a comic foil, doing a variety of pantomimes and pratfalls, and playing off LeRoy. The show grew into an elaborate circus-like spectacle with animals and dancers. The entire two-hour show, with a cast of 22 people, required two entire baggage cars to be transported by train. It would only grow bigger over time.

Adding Leon Bosco to the act proved to be a huge success. He eventually left the show to team up with another performer, but that act failed to catch on. Over the ensuing years, six other men performed as “Bosco” alongside LeRoy and Talma. First was a man named MacLaube, followed a short time later by a man named Daly, then Wilmot Hastings, and then by a heavy-set physician named James W. Elliott (who shaved his head and wore padding to play the part). The last two Boscos were men named Barley and Mullens. Outside of Dr. Elliott, little is known of these other performers. In later years, the character was promoted as Francisco L. Bosco, which was the stage name of an Italian magician from an earlier time.

The Asrah Illusion

LeRoy was always experimenting with new illusions and tricks. He had found a way to make a playing card appear to float in midair and then vanish. Leon Bosco said, “Why LeRoy, if you can do that with a playing card, why can’t you do it with a woman?” After a few weeks, LeRoy had created what he initially called “The Mystery of Lhassa.” But he was dubious about performing it publicly, thinking audiences would simply not believe the illusion.

He kept the trick under wraps for five years. Finally, in what was intended to be a one-time-only attempt, LeRoy performed the illusion in Johannesburg. Bosco waited in the wings with a big tray of crockery. If the trick had failed to win over the audience, Bosco would rush in and stage a noisy pratfall.

Weeks later they were back in London, and what was now being called the “Asrah Illusion” was still in the act, but was considered a lesser trick, and every night Bosco waited in the wings with his crockery, just in case. But he never needed it.

Soon it was being hailed by one theater operator as “the greatest illusion people had ever seen. It’s among the most famous magic tricks in human history, the famous ‘levitating lady.’”

In this illusion, a woman (Talma) would appear to be placed in a hypnotic trance by LeRoy. She would then lie down on a table and be covered with a silk cloth. The table would float in the air, up to a height of about eight feet. The table would then be removed, leaving only the woman’s prone figure, covered by the fabric, floating in midair. LeRoy walked around and underneath the floating body, and then passed a large hoop over it, showing that there were no ropes or supports. Finally, LeRoy would seize the corners of the cloth and pull it away with a flourish, revealing the woman had vanished. Talma then re-entered the stage from the wings—to thunderous applause.

This illusion was so famous that even Thomas Alva Edison once cited it as an outstanding example of the power of imagination. LeRoy went to great lengths to prevent discovery of the secret behind his famous illusion, something he was able to do for many years. Eventually, a trunk was rifled, and a crucial wire frame used in the illusion was stolen, giving away the gist of the trick. In response, LeRoy began selling the trick to others and instructing them on the best way to make it work.

It was this, LeRoy’s skill in inventing new tricks that would be used for decades by others, for which he is most famous. Over the years, he would be credited with inventing the famous illusion of sawing a woman in half, the “Hindu Rope” trick, and others. But while he was renowned for his inventive genius and workmanship, there is no evidence that those illusions were, in fact, invented by LeRoy.

for a fee, or else simply work up their own version and claim it as their own invention. Most

leading magicians during the Golden Age performed many of the same tricks.

In this regard, LeRoy was like most magicians. His act consisted of illusions he had invented along with the best magic tricks he had seen performed by others. He had a unique talent for seeing a great illusion performed by another magician, and then figuring out how it worked. He would make his own improvements and then incorporate it into his act. Enthusiastic newspapermen tended to attribute the origin of every magic trick to LeRoy, but what he often did was improve on the ideas of others, supplementing his own inventions. He may not have invented the Hindu Rope trick, but he may have offered audiences the best version of it. Some of LeRoy’s most famous illusions were named “Quick,” “Rostrum,” “Trunk of All Nations,” “The Transmigration of Souls,” “Jam Illusion,” and “The Prisoners and Cremation,” which he later renamed, “Burning a Woman Alive.” Variations on these illusions are said to be a part of contemporary magic performances even today.

LeRoy’s company was in great demand and they alternated living and performing in London and New York City. Soon they were touring worldwide and were as acclaimed as any of the Golden Age greats. The Monarchs of Magic were star attractions on a world tour in 1914 when war broke out in Europe and they found themselves stranded in Australia. LeRoy decided to return to the U.S. rather than to London. By 1915, the Monarchs of Magic traveling show was said by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch to feature “Three African lions, 100 other animals, 50 illusionists, fakirs and jugglers, and three carloads of paraphernalia.” Of these, only the three carloads figure seems credible, but it speaks to the extraordinary spectacle that the LeRoy magic show had become during this period.

One example is an illusion invented by LeRoy involving real lions that was called “Nero, or, Thrown to the Lions.” The entire stage was decorated as a Roman set, with a real cage holding lions. Costumed cast members acted out an elaborate skit in which Talma was miraculously saved from the lions by LeRoy. The image above shows just how elaborate this one illusion was as just one part of the Big Show.

Just how realistic and convincing were LeRoy’s illusions? In 1921, a San Francisco man filed a lawsuit against the Orpheum Theater and Realty Company there, where the Monarchs of Magic (who continued using the appellation “triple alliance” as well) were scheduled to perform. This man was convinced that Talma simply had to suffer pain and discomfort—or a fatally worse outcome—from being sawed in half by LeRoy. Fearing Talma would actually be cut in two, the suit sought an injunction against the theater. The performances went on as scheduled. The promoters seized on this publicity and began hyping the sawed-woman act to drive attendance.

LeRoy and Talma Move to Keansburg

During this era, the biggest and most famous magic shop in New York City, Martinka & Co., was owned and operated by an Austrian, Francis (Frank) J. Martinka, and his brother Antonio. Frank’s wife, Pauline, was his “chief assistant” in the 38 years the brothers kept the shop at 493 Sixth Ave. in Greenwich Village. It became a gathering place for the world’s great conjurers. On May 10, 1902, the Society of American Magicians (SAM), “the oldest and most prestigious magical society in the world,” led at times by leading names such as Houdini, had been formed there. As an example of just how popular the genre of magic was at that time, SAM used the 3,000-seat Carnegie Hall for its annual conference. Servais LeRoy was a regular visitor to Martinka & Co. and a SAM member. He became good friends with many famous magicians, but he formed a special bond with legendary escape artist and entertainer Harry Houdini. While he greatly admired Houdini’s escape acts and death-defying illusions, he found Houdini’s abilities with more standard magic tricks “fair, yet seldom brilliant.”

The growth of convenient steamboat travel from New York City had made the Raritan Bayshore region an attractive area for new development in the years before World War I. In 1906, several Highlands businessmen launched a business called New Point Comfort Beach Company and purchased land in Keansburg equivalent to ¾-mile of beachfront property. Frank and Pauline Martinka began speculating in Keansburg real estate in 1913. The couple purchased two of the New Point Comfort Beach lots, and the following year purchased two more. There is a newspaper reference to a “Villa Martinka” boarding house in the New Point Comfort Beach area, but no additional information seems to exist about this.

In the summer of 1917, Frank Martinka took ill. On Saturday, July 21, 1917, Harry Houdini came to Monmouth County, accompanied by his wife, Bess, his brother and fellow magician Theodore “Hardeen” Weiss, and a group of fellow conjurers from New York City, to visit Martinka and wish him a speedy recovery. Among the group were Servais LeRoy and Talma. Sadly, Martinka remained in poor health, and in June of 1918, he sold his magic shop, and retired to Keansburg. The magic shop changed hands several times, at one point even being owned by Houdini, and a version of it still exists today, in Midland Park, N.J., in addition to an online offering of magic tricks and supplies.

to the right of the pillar. While they were there as a part of this group visit, it is not believed

that either Servais or Mary LeRoy are in this photograph.

Meanwhile, Servais and Mary fell in love with the Keansburg area, and in 1918, they settled their magic company there, which served as their residence and base of tour operations thereafter. Servais, Mary, and Charles LeRoy lived together in a house at 355 Carr Avenue. Later the LeRoys moved to a new, smaller home at 84 Lincoln Court, where they were joined by Elizabeth Ford. A rusty lion cage remained in the backyard for many years, a sign of the company’s better days. It is not known where the person or persons who portrayed the Bosco character lived during these years.

While living in Keansburg, LeRoy created entire magic shows for other magicians, such as The Great Carmo. A warehouse in Keansburg was piled to the ceiling with trunks of LeRoy’s theatrical equipment. LeRoy even stashed excess trunks at the local American Legion.

LeRoy became active in local activities and helped found the Civic Association to drive improvements in the Keansburg community. He also performed magic tricks at various charity events around Monmouth County.

On October 24, 1930, Servais LeRoy, now age 65, stepped off the sidewalk in Matawan and was struck by a car and severely injured, suffering a concussion and broken ribs. Mentally and physically, he was never the same again. With a much-ballyhooed return to the Carlton Theatre in Red Bank, attempts were made to stage LeRoy’s “Big Show” once more, but Servais could no longer remember the lines or how the tricks worked. He went back into retirement, where he would have been well-advised to remain, but some promoters coaxed him into one last performance in New York City on June 6, 1940. Unable to perform up to his normal standards, LeRoy’s final appearance proved to be a humiliating disaster. It was the end of a brilliant career.

Realizing he could no longer perform, LeRoy quietly supervised the removal from storage of his magic tricks, supplies, equipment, and promotional materials. He had everything taken to the local dump and burned. Neighbors remembered seeing colorful Chinese boxes and curious items among the rest of the trash waiting to be picked up in front of LeRoy’s house.

Talma Leroy died in 1944 at age 70. Servais LeRoy died on June 2, 1953, age 88. Wearing his stage attire, he was buried at Fair View Cemetery in Middletown, next to his wife.

The great magicians Servais and Talma LeRoy were largely forgotten and had become anonymous figures in their later years in Keansburg, but they nevertheless succeeded in creating a lasting legacy through their inventive illusions that still endure and astound audiences today.

Unusual Sources

The main source for most of the information in this story comes from a self-published manuscript by William V. Rauscher. Rauscher had become fascinated with magic while a boy living in the Raritan Bayshore region, when he learned that the great Servais LeRoy lived nearby. While he never met LeRoy, who was by then years into his retirement, Rauscher became friends with Talma’s sister, Elizabeth Ford, and over the years corresponded with, and spent time visiting her, compiling memories and stories from the past decades of LeRoy family entertainment glory. After retiring as rector of the Christ Episcopal Church in Woodbury, N.J., Rauscher finally published his biography of LeRoy in 1984, which includes LeRoy’s own memoirs. LeRoy wrote this when his memory was no longer always reliable, so some of it, for example, the dates provided, must be taken with a grain of salt.

Another fascinating source is a television series produced in the U.K. called Illusions. Actor Adam Wide and director Daphne Shadwell staged a re-enactment of LeRoy’s Asrah Illusion in a single-take, unedited videotaped performance, with Wide as Servais LeRoy. In Illusions, some of the greatest acts from the Golden Age of Magic were re-created; unfortunately, aside from a handful of material posted to YouTube, only a handful of such re-creations survive from this series. In all likelihood, it was one of the many television series produced for the BBC during the early years of videotape, which was then a prohibitively expensive recording medium. To save money, the BBC was in the habit of simply re-using videocassettes, a common practice for years, but one that resulted in the permanent erasure of hundreds of shows and performances, even including perennial favorites such as Doctor Who. The Illusions recordings were likely destroyed after the show stopped airing. Fortunately, the episode of Illusions dealing with Servais LeRoy’s Asrah Illusion is still available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7c948LItXX0

Sources:

Amusements. (1916). The Burlington Free Press, Burlington, Vt., September 23, 1916, P. 6.

Around Keansburg. (1943). The Keansburg News, Keansburg, N.J., April 30, 1943, P. 16.

Coming to the Theaters. (1898). The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, Mo., September 17, 1898, P. 2.

Connelly, Eugene Le Moyne. (1913). A Twelve-Act Vaudeville Bill. The Pittsburgh Daily Post, Pittsburgh, Penn., September 14, 1913, P. 16.

Desfor, Irving. (1984). Great Magicians in Great Moments. Lee Jacobs Productions, Pomeroy, Ohio, 1983, P. 173.

Figdore, Sherry. (2000). Book revives real-life legend of conjurer from Keansburg. Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., June 20, 2000, P. 6.

Fitzpatrick, J.H. (1915). In Advance of Theatrical Globetrotters. The Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Penn., March 14, 1915, P. 22.

Hays, Richard E. (1915). Many Notable Attractions Booked for Remainder of Tacoma Season. The Daily Ledger, Tacoma, Wash., January 17, 1915, P. 19.

Jean Henry Servais LeRoy. (1953). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., June 5, 1953, P. 2.

Magic Exponents of a High Order at the Temple Thursday Night. (1916). The Daily Republican, Kane, Penn., March 20, 1916, P. 2.

Magician Injured. (1930). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., October 29, 1930, P. 11.

Magicians Visit Keansburg. (1917). Keyport Weekly, Keyport, N.J., July 27, 1917, P. 2.

New Point Comfort. (1906). Keyport Weekly, February 23, 1906, P. 1.

O’Connor, Eileen. (1918). Passing of Black Magic Ends City Landmark. The Sun, New York, N.Y., June 9, 1918, P. 49.

Rauscher, William V. (1984). Monarch of Magic. Self-published manuscript by the author.

Real Estate Transfers. (1913). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., August 21, 1913, P. 8.

Real Estate Transfers. (1914). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., June 11, 1914, P. 3.

Real Estate Transfers. (1917). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., July 20, 1917, P. 13.

Real Estate Transfers. (1920). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., August 23, 1920, P. 2.

Rossen, Jake. (2017). Wipe Out: When the BBC Kept Erasing Its Own History. Mental Floss, August 2, 2017. Available: https://getpocket.com/explore/item/wipe-out-when-the-bbc-kept-erasing-its-own-history?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Royal Aquarium – This Day. (1890). The Standard, London, England, March 6, 1890, P. 1.

“Sawing Wife in Two” Causes Suit for Injunction. (1921). The Buffalo Times, Buffalo, N.Y., November 16, 1921, P. 12.

Ziegfeld Follies Now at Olympic, Opening Tonight. (1915). St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 14, 1915, P. 8.

my grandfather harry greener worked for servais leroy when he was young – in his20’s as part of the acts – as a ‘double’ ihave a copy of the book by Wm Rauscher – a gift from him[number200]