On December 13, 1943, Naval Ammunition Depot Earle was commissioned. The facility, which sits on 11,000 acres in Monmouth County, was designed to provide for the safe and secure storage and transfer of ordnance – bombs, bullets, missiles, torpedoes, depth charges, etc., any kind of military ammunition or materiel.

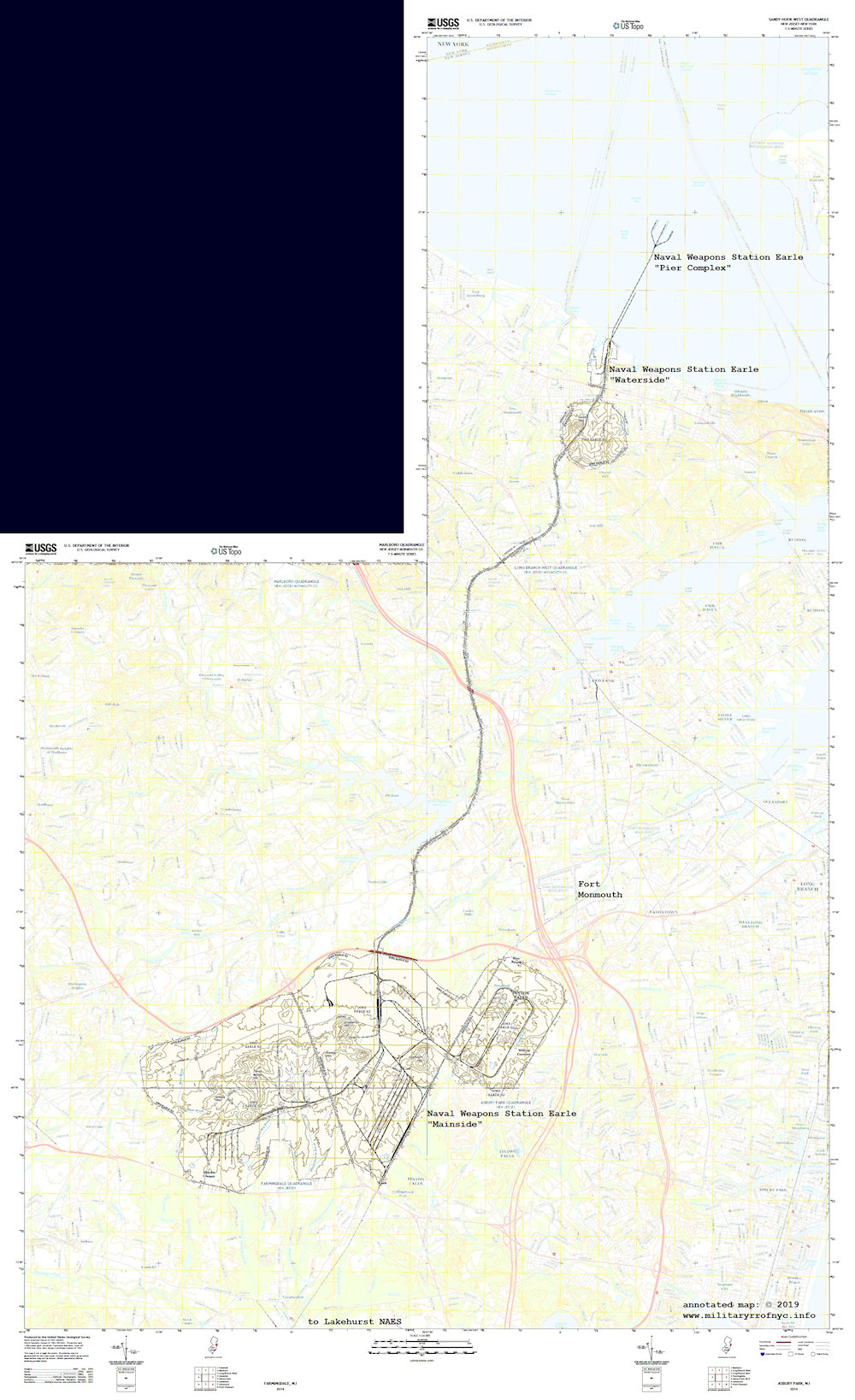

The station is divided into two sections: Mainside, located in parts of Colts Neck Township, Howell Township, Wall Township, and Tinton Falls; and the Waterfront Area (which includes the pier complex), on Sandy Hook Bay, located in the Leonardo section of Middletown Township. The areas are connected by Normandy Road, a 15-mile (24 km) military road and rail line.

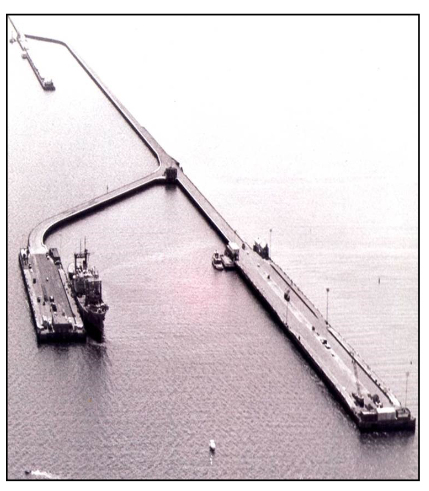

Today known as Naval Weapons Station Earle (NWS Earle), the facility is named after Rear Admiral Ralph Earle, the chief of the Bureau of Ordnance during World War I. Its distinguishing feature is a 2.9-mile (4.7 km) pier in Sandy Hook Bay where ammunition can be loaded and unloaded from warships at a safe distance from heavily populated areas.

The mission of NWS Earle is to provide all ordnance for all Atlantic Fleet Carrier and Expeditionary Strike Groups, and support strategic Department of Defense ordnance requirements. The officers, staff, and civilian workers at NWS Earle maintain and operate the Navy’s premier ordnance transshipment facility, “to sustain the fleet, enable the fighter, and support the family.”

The Need for Safer Ordnance Transshipment

A number of horrifying and disastrous explosions over the years made it increasingly clear to both military and civilian leaders alike that new solutions were needed to address the need to have safe and secure facilities to store and supply ordnance.

On July 30, 1916, German saboteurs succeeded in detonating ordnance being stored at Black Tom Island off Jersey City, in New York Harbor, destroying U.S.-made munitions that were to be supplied to the Allies in World War I. The explosions killed four people and destroyed some $20,000,000 worth of military goods, and damaged the Statue of Liberty. It was one of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions in history.

On October 4, 1918, the T. A. Gillespie Company Shell Loading Plant, sometimes called the Morgan Munitions Depot, a World War I ammunition factory in the Morgan area of Sayreville in Middlesex County, was the site of a number of huge explosions. The initial explosion, generally believed to be accidental, triggered a fire and subsequent explosions that continued for three days, totaling approximately six kilotons, killing about 100 people and injuring hundreds more. The facility, one of the largest in the world at the time, was destroyed along with more than 300 surrounding buildings, forcing the evacuation and reconstruction of Sayreville, South Amboy, and Laurence Harbor (Old Bridge). While hundreds of detonations were spread over three days, the totality of the event ranked as one of the largest man-made non-nuclear explosions in history. Some of the strongest individual blasts, from exploding storehouses or railcars of ammunition, broke windows as far away as Manhattan and Asbury Park, more than 20 miles (32 km) distant.

A New Solution Needed

Long before the opening hostilities of the Second World War, high-ranking officers of both the Army and the Navy realized it would eventually be necessary to establish a base for the loading of explosives somewhere in the Port of New York, a focal point for all important rail lines of the country. By 1943 the need had become urgent. The declaration of war had vastly increased shipments of explosives, with the bulk of the loading falling upon Caven Point Army Depot in Jersey City. During both World Wars, Caven Point’s proximity to key rail networks and the ports of New York and New Jersey made it invaluable for the marshalling of troops, munitions and materials heading for front lines in Europe. However, because of its proximity to densely populated areas, and proximity to military facilities, Caven Point was considered an extreme hazard. Planning for a new facility was hastened in early 1943 after the ammunition ship SS El Estero caught fire while moored in Bayonne.

Studying the problem, the Army and the Navy reached the same conclusion: the south side of Sandy Hook Bay was the ideal strategic location. A coastal site in the Leonardo section of Middletown was selected, along with a large unimproved area of Monmouth County 12 miles to the south. The two areas were connected by a secure direct rail and road corridor now called Normandy Road.

Collectively, the new facility provided the desired proximity to commercial rail facilities, New York City, New York Harbor, and the open ocean, yet was a safe distance from dense populations, bridges, tunnels, and shipping channels. Initially estimated to cost $25 million, a reduced $14 million plan was approved by the Secretary of the Navy, and on August 2, 1943, construction began on what was to be Naval Ammunition Depot Earle.

After construction began, the War and Navy Departments collaborated to expand the project to include facilities for Army ammunition. During construction, land was acquired from a number of sources including the camp site of Boy Scout Troop 67 of Red Bank, 33 acres at Hominy Hills. A major challenge for the project’s planners was the acquisition, purchase, and transfer of many small real estate tracts to enable a secure corridor from Colts Neck to Leonardo.

During construction of the base, there was a concern for the safety of workers from the threat of hunters, who had used the woods around Colts Neck for decades to hunt deer and other game. In addition to signage throughout the area, ads were placed in local newspapers warning hunters to steer clear of the newly reserved federal property.

Substantially complete by June 1, 1944, the cost for NAD Earle ultimately totaled $51.8 million. Quickly the focal point for ordnance shipping, NAD Earle loaded the majority of ammunition used by the Allies for the World War II D-Day invasion of Normandy, an achievement for which Normandy Road is so named.

A detachment of about 60 U.S. marines were deployed as guards at the base when it first opened, and all of these marines were veterans of “heavy fighting” in Guadalcanal, New Guinea, or elsewhere in the South Pacific in World War II. It was said that every one of these men “have suffered some disability,” and that “nearly all of them suffer from malaria.” The marine guards were treated to a lavish celebration at the Rainbow Room in New York City, which was otherwise closed during wartime. The funds for this celebration came from civilian employees at Earle. Later, contractors and trade unions building the base sponsored parties honoring the marines at the Hotel Albion in Asbury Park.

The first administrative building at NAD Earle was called the “Red Funnels,” an abandoned tavern on Route 34 constructed in the form of a ship; this nautical creation no longer exists.

A Proud Legacy of Safety and Integrity

NAD Earle continued to develop after World War II, keeping pace with the changing needs of the Navy and Department of Defense during the Cold War. The value of NAD Earle was demonstrated vividly on April 30, 1946, when the USS Solar, a U.S. Navy Buckley-class destroyer escort (DE 221), exploded at the Earle pier in Leonardo, killing seven sailors and injuring 125 others. The blasts rattled windows for miles, but caused no damage or injuries to any civilians or buildings in the area.

On February 27, 1953, five witnesses from Monmouth County testified before the New Jersey Law Enforcement Council in Newark regarding operations at the NAD Earle in Leonardo, by now commonly known as “the Navy Pier.” Among these witnesses were Pasquale and Nancy Simonetti, proprietors of the Piano Bar in Long Branch. Nancy was daughter of the notorious mob leader Vito Genovese from his first marriage. Another witness was Thomas Calandriello of Shrewsbury, described as a “loading gang boss,” and whose daughter Rose was married to Vito’s son Philip. The investigation was triggered when the Navy reported that its “elaborate security system” had failed to prevent “loan sharks, bookmakers and the numbers racket from thriving among longshoremen employed at Leonardo.” Proceedings of the hearing were not disclosed, and no charges were ever brought. On March 17, 1953, the commander of NAD Earle formally barred Calandriello from the installation as a “poor security risk.” Capt. Paul C. Wirtz denied the ouster was connected to Vito Genovese, saying that the decision was based on an investigation that had been underway for some time, and which proceedings were not disclosed.

In 1974, Earle’s name was officially changed to Naval Weapons Station Earle. In subsequent years, Earle proved its strategic worth as the transshipment site for ordnance used in Operation Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom.

On November 8, 1977, during a storm, the Steamship Alexander Hamilton caught fire and sank next to the Navy Pier, where she remains to this day, off-limits to visitors. In her heyday, she carried 3,500 passengers on various excursions and point-to-point passenger transportation. She was the last of the great Hudson River “side-wheelers.”

The temptation to skip the summer beach traffic and zip down Normandy Road to get to the shore might seem like a minor risk, but note that anyone found traveling Normandy Road without permission is required to come before a United States magistrate, where they will be assessed a fine of between $100 and $500, and can face up to 30 days in jail. The road is constantly monitored and patrolled, and there is a zero-tolerance policy for violators.

Sources:

Berger, Meyer. (1946). Naval Ship Disaster: Warship Blows Up at Munitions Pier in Port, Killing Five. The New York Times, New York, N.Y., May 1, 1946, P. 1.

Contractors and Unions Fete Marines at Depot. (1943). Matawan Journal, Matawan, N.J., December 23, 1943, P. 5.

Earle Naval Weapons Station. (2022). U.S. Military Bases, MilitaryBases.us, Owens Cross Roads, Ala. Available: http://www.militarybases.us/navy/earle-naval-weapons-station/

Hunters Warned Away from Naval Depot at Earle. (1943). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., November 4, 1943, P. 1.

Government Takes Over Scout Camp. (1943). The Daily Register, Red Bank, N.J., December 9, 1943, P. 19.

Marine Vets Guarding Depot Feted. (1943). Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., December 22, 1943, P. 3.

NWS Earle Public Affairs. (2018). Earle Celebrates 75th Anniversary. The Missile Express, NWS Earle, February 1, 2018. Available: https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/AA/00/06/39/26/00013/02-01-2018.pdf

Welcome to Naval Weapons Station. (2022). Commander, Navy Region Mid-Atlantic, United States Navy. Available: https://cnrma.cnic.navy.mil/Installations/NWS-Earle/.

The Leonardo Piers seen from the air. Photo by Mcicogni, used under terms of Creative Commons, Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Leave a Reply