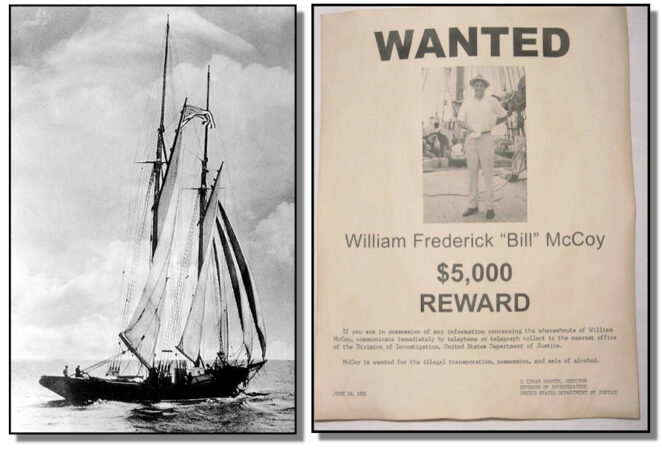

On November 25, 1923, Bill McCoy, possibly the most celebrated bootlegger of the Prohibition era, found his career as a smuggler at an end at the hands of the U.S. Coast Guard, off Sandy Hook.

He was born William Frederick McCoy on August 17, 1877, in Syracuse, N.Y. He trained to be a seaman in Philadelphia and proved to be talented in many areas, including yacht building. But during the Great Depression, demand for luxury sailboats dropped precipitously. With the advent of Prohibition, and in dire need of a way to make money to say alive, Bill McCoy and his brother Ben decided to get into the liquor smuggling trade.

They sold their Florida boatyard business and invested the proceeds into a series of increasingly larger and faster vessels before finding the ship that would always be the lifelong favorite of the seaman Bill McCoy. The Arethusa was a fishing schooner, 127 feet, 157 tons, designed by Thomas F. McManus in 1907 and built by James and Tarr in Essex, Mass., in 1909. This sailboat could outrun tramp steamers and after alterations by McCoy, was among the fastest commercial sail vessels on the Atlantic coast. She was capable of carrying 6,000 cases of illegal alcohol.

McCoy is credited with conceiving the “Rum Row” method of smuggling, where larger ships stayed just beyond the three-mile U.S. territorial limit, selling to locals in small high-powered boats that could outrun Coast Guard cutters and take advantage of the many hidden inlets and waterways along the coast. This idea caught on immediately, and in time a line of ships could be viewed from the beaches of the Jersey Shore, from Sandy Hook to Atlantic City. Eventually, Rum Row became a fully-fledged regatta: Up to 100 boats at a time sat offshore, with jazz bands and tourists coming out, and Bill McCoy was the undisputed king. Prostitutes came out and plied their trade aboard the Rum Row vessels, where they would get twice their shore price for their services.

McCoy renamed his new ship Tomoka so as to be able to register it in Great Britain and be that much further beyond the reach of U.S. law enforcement. He and his eight-man crew sold cases of nine liquor bottles stacked 1-2-3, wrapped in burlap packages called “hams” or “sacks.” McCoy’s transit papers typically stated Tomoka was moving liquor from one legal port, Nassau, Bahamas, to another, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Even if he never made Halifax, there was no law stopping McCoy from selling his cargo on the high seas en route. As long as McCoy stayed in international waters, he broke no rules.

Believing that he was not committing any crime, McCoy was happy to fuel the American public’s fascination with smugglers, moonshiners, speakeasies, and other aspects of the resistance to Prohibition. He was the subject of fawning newspaper coverage, which he welcomed. But this rankled U.S. government officials, and led to his downfall.

McCoy’s operation grew to five boats, running crews of dozens of men on monthly trips to Rum Row, transporting an estimated two million bottles over his short-lived career. When Tomoka would reach the row, McCoy’s brother Ben would come out with supplies, fresh water, newspapers, fresh meat, vegetables, and tobacco, so the ship never had to make port.

Bill McCoy was known to pay his debts, and did not dilute his spirits, as others did. His rum was known as the gold standard, and he set the price by getting top dollar — so much so that his rates were published as the given for Rum Row. As a result, McCoy was one of the most brazen and successful bootleggers of the Prohibition era. He had once been busted with 1,500 cases of liquor off of Atlantic City in 1921, but in 1923, he returned to the Jersey Shore to once again cash in on the unquenchable demand for illicit alcohol.

On the morning of November 25th, McCoy was off the coast of Sea Bright, safely in international waters. With the U.S. authorities tired of his flaunting of the law, the command had been given to bring Bill McCoy to justice. The Coast Guard cutter Seneca sent a whaleboat to examine McCoy’s papers, even though he was outside of U.S. territory. The State Department had gotten the British government to agree not to interfere if the British-registered Tomoka had to be chased down. The lieutenant in charge claimed there was something wrong with McCoy’s papers and ordered him to bring the boat to Sandy Hook. McCoy refused. The Seneca was ordered to bring Tomoka in or sink her.

McCoy turned his ship and headed out to sea. After a chase of a few miles, Seneca fired a shell across Tomoka’s bow. McCoy’s men returned the fire with a machine gun set up on her forward deck. The machine gunners ran to cover when the shells of the Seneca began to fall so close to their mark that they kicked up the spray over the Tomoka’s deck.

The Seneca lobbed four shells into the water in front of McCoy’s boat. McCoy knew better than to continue the fight. He lowered his jib. The smuggling vessel stopped, and the Coast Guard overtook it. When the Coasties went aboard and searched the ship, they found McCoy down below, surrounded by 400 cases of whisky. According to the Coast Guard, it was all that was left of a massive 4,200 case shipment McCoy had brought up from the Bahamas. McCoy had $60,000 on him when he was searched. As they started the 17-mile trip to Sandy Hook, one by one McCoy took his crew below, paid them their wages, and said goodbye.

After his arrest, reporters asked McCoy what defense the accused planned to make at his upcoming trial. “I have no tale of woe to tell you,” McCoy said. “I was outside the three-mile limit, selling whisky, and good whisky, to anyone and everyone who wanted to buy.”

McCoy also had in his favor the fact that as a smuggler, he had “never paid a cent” to organized crime, politicians, or law enforcement for protection.

In March 1925, after almost two years of legal wrangling, McCoy was sentenced to serve just nine months in prison. A celebrity of his day, he was even permitted to leave the jailhouse daily as long as he returned by 9:00 p.m. He once even attended a prizefight in ringside seats at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, with the warden of his prison. When he got out, he found the rum-running competition had greatly increased, and he withdrew from the bootlegging game for good.

Many think he is the inspiration behind the popular phrase, “The Real McCoy,” a reference to the undiluted high quality liquor that Bill McCoy was famous for selling, but researchers have identified that phrase as having been in use as far back as 1908, and so while its true source remains a matter of conjecture, it is highly unlikely it originated from America’s favorite bootlegger. It was certainly applied to him and his products during his smuggling years, and he was happy to embrace the sobriquet. In 1933, long retired from smuggling, McCoy for a time sold his own personal brand of whisky, calling it “The Real McCoy,” with an illustration of his beloved Arethusa on the label.

After prison, McCoy returned to boat-building in Florida and died on December 30, 1948, in Stuart, Fla. His fame as perhaps the single most prominent ocean-going smuggler of the Prohibition era is reflected in Bill McCoy being among the true-life characters portrayed in HBO’s award-winning series, “Boardwalk Empire,” about the illicit liquor-fueled origins of Atlantic City. Boardwalk Empire features the most famous icons of the Prohibition era, including Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, and the great captain Bill McCoy. It’s important to note that while this series portrays characters from real life, the program depicts primarily fictitious events.

Sources:

Arethusa by Elia – 1907 Knockabout Banks Fishing Schooner. (2014). Available: https://modelshipworld.com/topic/409-arethusa-by-elia-1907-knockabout-banks-fishing-schooner/

Deitche, Scott M. (2018). Garden State Gangland: The Rise of the Mob in New Jersey. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Md., P. 12-13.

Dermody, Ann. (2015). The Real McCoy. BoatUS Magazine, June/July 2015. Available: https://www.boatus.com/magazine/2015/june/the-real-mccoy.asp

Don, Katherine. (2010). How real is “Boardwalk Empire’s” Al Capone? Salon.com, October 11, 2010. Available: https://www.salon.com/2010/10/11/boardwalk_empire_al_capone/

Sea Rumrunner Held on 2 Liquor Charges. (1923). The New York Times, Tuesday, November 27, 1923, P. 21.

I re enacted Mrs McCoy in Holly Hill Fl. At the home, Riverside Dr. Serving a little booze and cheese and crackers dressed appropriately as folks toured the family home. Also painted the Arethusa in wc for the HH Museum of which I am a lifetime member, a volunteer for many years. There is a book on Amazon titled Gnomes of HH, which I illustrated.

Just a little brag at age 84!