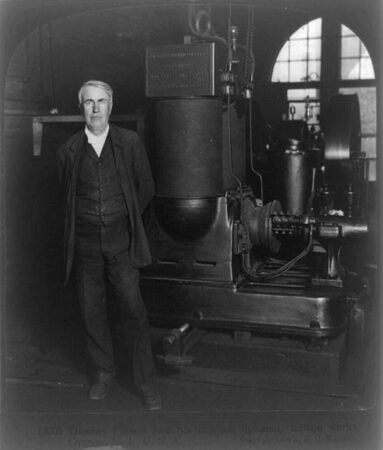

Editor’s note: Thomas Alva Edison (born February 11, 1847, Milan, Ohio; died:October 18, 1931, West Orange, N.J.) was “America’s Genius Inventor,” a man who averaged one patent for every 10-12 days of his life, including the incandescent light bulb, the phonograph, the X-ray, moving pictures, and hundreds more. Edison developed most of his greatest inventions at his compound in Menlo Park, at that time a part of Raritan Township in MIddlesex County, N.J. (the town is now called “Edison”), and neighboring West Orange. Edison’s voluminous achievements have been thoroughly chronicled in biographies, museums, documentaries and many other sources. As per Monmouth Timeline policy, we will not replicate that which has been done so well elsewhere, and focus only on that which pertains to Monmouth County.

At the Onset of World War I, Thomas Alva Edison Threatens to Quit as Advisor to the Navy Unless his New Research Lab is Located at Sandy Hook

On March 7, 1917, legendary inventor Thomas Alva Edison sent a letter to the Secretary of the U.S. Navy and said he would quit the Naval Consulting Board that he had conceived, created, and chaired, if his proposed new research laboratory was built anywhere other than Sandy Hook. This time, for once, the Wizard of Menlo Park would not get his way.

Edison’s involvement with the Navy began in 1910, when he was approached by representatives to see if he could adapt his alkaline nickel-steel battery, perfected for powering electric cars and trucks, to power submarines. At this time submarines were very new and largely unreliable, with batteries being a limiting and very hazardous factor. The officers told Edison that “it was his duty” to help the Navy solve one of its most dangerous problems. Edison had always sparked to challenges involving his inventions and technologies, especially when a potentially lucrative defense contract loomed as reward.

Yet this came at a time when Edison was also still working on some of his higher priorities, especially moving pictures with sound, and he assigned the submarine battery project to others. Edison, an avowed pacifist, had eschewed interest in inventing weapons and war systems, but the sinking of the RMS Lusitania by a German U-boat in 1915 stirred him to make defense technology a personal priority.

To the surprise of no one who knew him, once Edison turned his mind toward all things military, the ideas poured out, from how the U.S. should prepare for the coming conflagration, to the composition of standing armies and navies. In a by-lined article in The New York Times, Edison also called for the government to “maintain a great research laboratory, jointly under military and naval and civilian control. In this could be developed the continually increasing possibilities of great guns, the minutiae of new explosives, all the techniques of military and naval progression.” Edison proposed, and was then asked to help establish a new “department of invention and development” for the Navy, along with a board of eminent civilian scientists to supervise its operations.

President Woodrow Wilson appointed Edison to the task he had proposed. Edison now bore the rank of Commodore, and when told he was to be measured for a uniform, said, “If I have got to wear a uniform, count me out. I want to be able to tell an Admiral to go to —- if he is in the wrong.”

Edison began assembling what would become known as the Naval Consulting Board, while continuing to call for the establishment of a new U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. He envisioned a facility built of “indestructible concrete somewhere along the Atlantic seaboard” on “tidewater of sufficient depth to permit a dreadnought to come to the dock.” There should be a large city nearby for ease of obtaining supplies, but the facility should not be so close to that city as to serve as a distraction to young researchers. It was to have a “manufactory,” equipped with a full range of shops, from a cast steel foundry and optical grinder to an explosives department, necessarily “separate from the main laboratory.” Edison was forced to abandon his notion that the facility would be entirely devoid of Navy oversight, agreeing to allow technologically qualified officers to run the facility, as long as they did not engender “too much red tape.” But the innovations were to come from the minds of leading minds from outside of the service. “The soldier of the future will not be a sabre-bearing, bloodthirsty savage,” Edison wrote; “He will be a machinist.”

Edison’s presented plans for his new research facility, comprising 13 buildings and eight shops. In 1916, Congress appropriated $2 million for the project. But the question of where the facility was to be located was looming as yet another battle to be waged.

Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels clarified that he had “no views…at all as to the place where it shall be located.” But privately, Daniels communicated to others that Washington, D.C., might be the best place.

But in the last weeks of 1916, Edison’s “main compulsion” was to persuade the other members of the committee deciding the location of the new laboratory to recommend Sandy Hook as the ideal place. He pointed to the close proximity to New York City as well as the Brooklyn Navy Yard, while not mentioning that it was also a similar distance to Edison’s West Orange, N.J. home and compound. He noted that Sandy Hook boasted a fort (Fort Hancock), and a proving ground. The nearby Highlands bluffs provided a vantage point ideal for testing marine visibility tests for submarine detection systems. Arguments against Sandy Hook were primarily based on its distance from the District of Columbia, which was precisely a quality Edison considered essential to the success of the project. “If the Lab is to be successful…it should be as far as Washington as possible.”

But other members of the committee preferred having the facility close to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis as an “intellectual resource.” Pragmatists felt that having the facility close to where those who would vote on its funding could visit it would better ensure its success.

The committee presented to Edison a letter for his signature that declared “We are unanimous in favor of Annapolis.” A key reason cited was the fact that existing government-owned land was available near Annapolis, eliminating a major cost. But the letter also called for a very different leadership model for the laboratory. Where Edison envisioned the facility being led by military, Naval and civilian scientists and experts, the committee’s recommendation was to have the facility led by a single Navy officer, responsible only to the Secretary of the Navy.

Edison was not a person accustomed to being thwarted. His breakthroughs often came through what observers called “sheer doggedness.” He was known for his “impatient willingness, compulsion, even, to take enormous risks.” After 40 years of having his laboratories constructed to his exact specifications in every way, Edison was outraged, believing that the project would generate theories, but not functioning weapons and defense systems to help the immediate war effort.

The great inventor responded with a 17-point rebuttal, arguing that the “uninhabited remoteness” of Sandy Hook was essential to security, that the dunes were perfect for “aeroplane” development, and that New York’s wealth of specialty machine and engineering shops could provide essential supplies on short notice. “I believe I am right in re Sandy Hook & of a Rapid Constructing Laboratory…and I am going to stick to it. I shall never attach myself to a dead Government operated concern. If I can’t get quick results & plenty of them, then I will not play the game,” Edison wrote.

In a rare defeat for Thomas Edison, the Naval Consulting Board he created rejected his position and approved the majority proposal for the location of the lab to be near the District of Columbia; it was acknowledged that the decision was more political than pragmatic. Edison’s response was typical of his dogged nature to stick to his guns no matter what. In a letter dated December 23, 1916, he had written, “I have it fixed in my mind, whether right or wrong, that the public would look to me to make the Laboratory a success, that I would have to do 90% of the work. Therefore if I cannot obtain proper conditions to make it a success I would not undertake it or be connected with it in the remotest degree.” Getting no satisfaction, three months later, on March 7, 1917, Edison threatened to quit the Naval Consulting Board in a letter to Daniels. Secretary Daniels coyly placed the letter aside and took no action.

Edison took ill around this time, and the Naval Consulting Board proceeded to move forward with plans for the research laboratory, minus its leading light.

Sources:

Morris, Edmund. (2019). Edison. Random House, New York, N.Y.

Baldwin, Neil. (1995). Edison: Inventing the Century. Hyperion, New York, N.Y.

Edison May Quit Naval Board. (1917). The Daily Record (Long Branch), March 7, 1917, P. 1.

Thomas A. Edison Here. (1917). The Daily Register (Red Bank), July 18, 1917, P. 1.

Leave a Reply