By William Gardell

January 1777: A Time of Tension

On January 2, 1777, members of the Monmouth County militia, along with a company of Continental army soldiers, reached what is today Freehold and engaged in a skirmish with a brigade of Loyalist recruits, a growing threat to the cause of independence in the region. The entire affair lasted about 15 minutes. There were about 200 Loyalists against some 120 men sent by George Washington to clear the Tories out of the County for good. Historian Michael Adelberg has called this “The First Battle of Monmouth,” but it would hardly be the last confrontation between local residents on either side of the conflict.

The history of Monmouth County during the American Revolution is a complex one. Leaders of the 13 British American colonies, including New Jersey, had declared a state of rebellion against the Crown. But within New Jersey, Monmouth County was arguably the scene of a state of insurrection by Loyalists against the Patriot-controlled state government throughout much of the war.

The revolution was a long, drawn-out event that changed over time. Individual Americans had different and changing loyalties. Some New Jersey farmers and merchants may have resented having to pay for taxes on tea, sugar, and other goods, which they had not been asked to do for generations, but that didn’t necessarily mean they felt that going to war against their sovereign was a good or just idea either. Some Loyalists stayed loyal out of a sense of moral duty to what they viewed as their King and country while others simply didn’t want to bet on the wrong horse and throw in their lot with a rebellion that would most likely fail. Others, both professed Patriots and Loyalists, changed their alliances with the fortunes of the overall war.

Some were opportunists who used either or both “causes” in order to rob their neighbors, taking goods and livestock away from political enemies, and who used the war as an excuse to hurt these “traitors.” One group of “Loyalists” became known as the Pine Robbers. What is now Howell Township was haunted by this group of bandits, led by Jacob Fagan and Lewis Fenton. They professed their loyalty to the King but robbed anyone they came across traveling on the lonely roads of western Monmouth County. In 1778 the State of New Jersey issued a $500 reward for Fagan and he was later killed by the Monmouth County Militia.

And in addition to all this, some used the war as an excuse to settle old scores with neighbors that had nothing to do with the fight for independence.

There are numerous examples of this, such as the killing of Middletown Patriot Militiaman Joseph Murray on June 8th, 1780, at the hands local Tories. Murray was born in Ulster County, Ireland, and had come to the New World with his mother in 1767. These Scots-Irish, including Murray, were Protestants, often of partially Scottish heritage, living in Northern Ireland. Many came to the New World in the early part of the 18th century, and many fought against the British Crown during the Revolution. Murray was shot and bayonetted to death while he was working on his farm. His home, which he built in 1770, still stands to this day in Poricy Park in Middletown, where it is maintained as a museum called The Joseph Murray Farmhouse.

Murray was likely killed by local Tories or men working for them, such as Edward Taylor of Middletown, whose horses had been confiscated by Murray earlier in the war, to be supplied to the Continental Army. Of course, the owners of those horses took great offense to this. Horses were one of the most valuable commodities one could own in colonial America, and were not easily replaced.

Many acts of violence during the war in Monmouth County were probably the result of a mixture of some of these motivations. In all, there were over 100 recorded skirmishes or raids conducted in Monmouth County during the American Revolution. The war in Monmouth County was neighbor against neighbor in truest sense of the phrase.

The County of Monmouth itself was somewhat divided based on who had settled where, and when. Freehold, or Monmouth Courthouse (or sometimes “Court House”) as it was then called, was settled largely by Dutch and then later Scottish settlers during the 17th century. This was the most important town of central/western Monmouth County as well as the county seat. Eastern Monmouth, including Shrewsbury and Middletown, also had some Scottish and Dutch settlers but these towns were dominated by English settlers, including some who recently arrived from England.

In some respects, the war in Monmouth County was a war fought between Anglicans on one side and Presbyterians and Dutch Reformed on the other. The Quakers, who were also mostly on English origin, largely sat in out when they could due to their pacifist beliefs. The English settlers were largely Anglicans and both Middletown and Shrewsbury had prominent Anglican Churches that were founded in 1702 (both of which still exist). These English colonists were not as likely to be Patriots as their Scottish/Dutch neighbors in the western part of the County, who had no particular loyalty to England itself, let alone King George III. The Scots had a long history of rebelling against the English Crown and had done so in Scotland as recently as the 1740s. National differences were supported by religious distinctions between these various groups as well.

Many Monmouth County residents continued to trade with Britain throughout much of the War, just as they had done before the war. New York City was occupied by the British Army from September 15th, 1776, when Gen. Sir William Howe’s forces landed in Manhattan. The British controlled Staten Island, Sandy Hook (which was an island at times during the 1700s), and New York City until the end of the war.

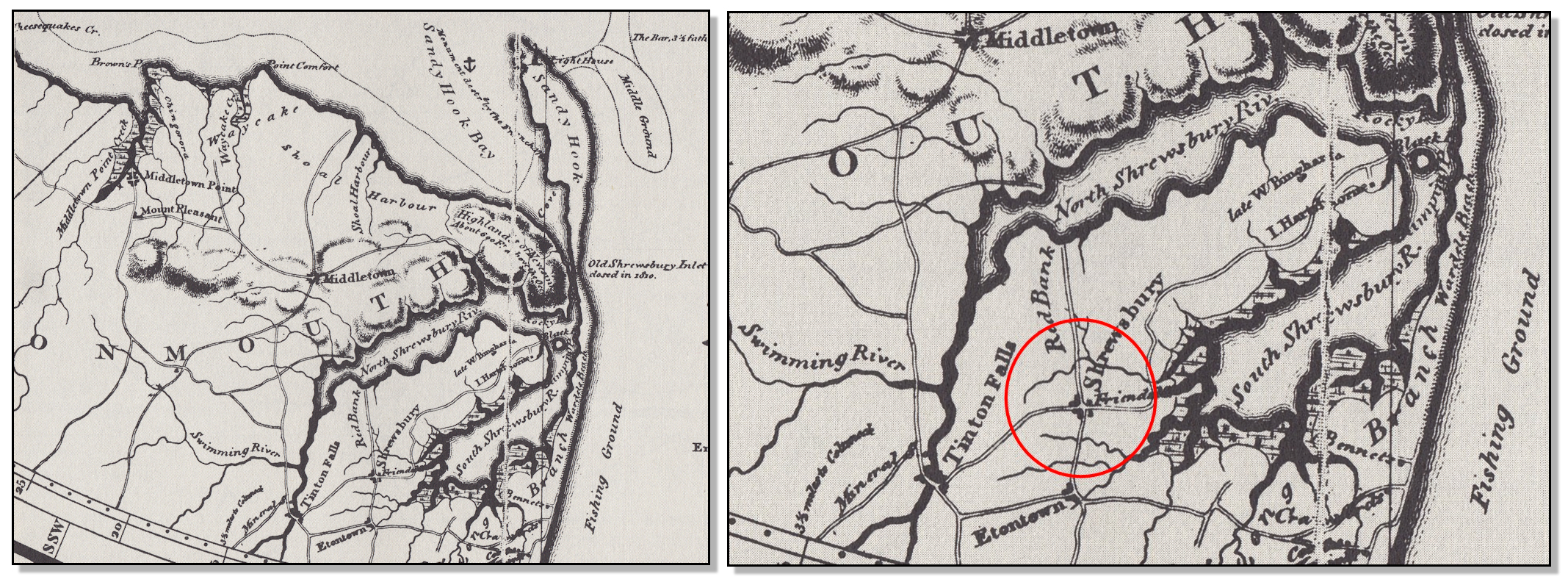

British and Loyalist forces launched numerous raids on Patriot-controlled Monmouth County throughout 1776-79 and beyond, including the assault by Skinner’s Greens on the Burrowes Mansion in what is today Matawan; the Razing of Tinton Falls; and the incursions of the guerilla band led by the escaped slave who became known as Colonel Tye. For the most part, these raids were successful, with Loyalists making off with livestock and other foodstuffs, guns, ammunition and gunpowder, and taking Patriot leaders hostage. The important men would often be used in prisoner exchanges, and the rest ended up in a British prison.

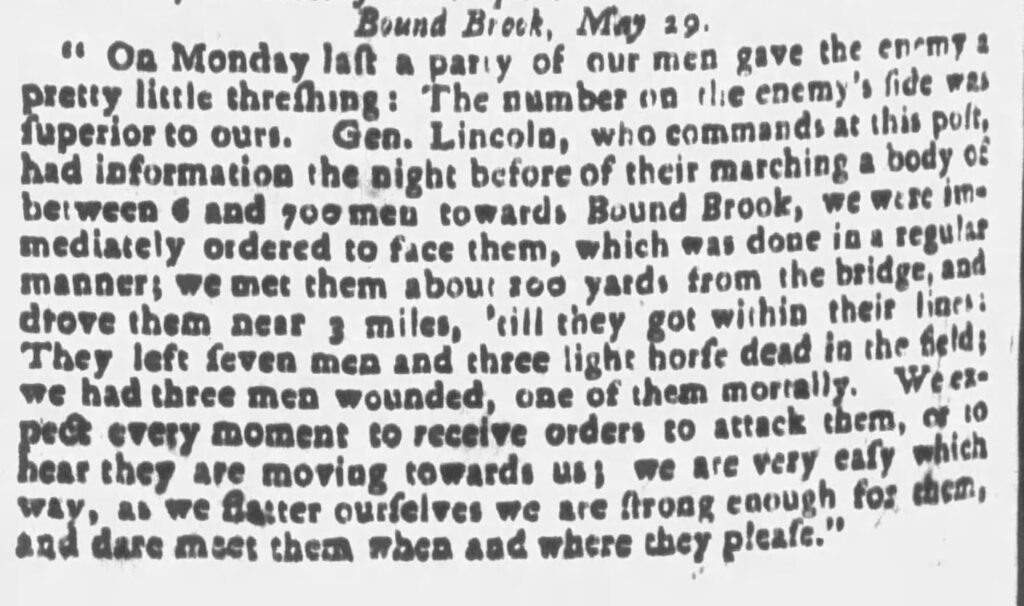

The British/Tories were not always so successful. The Patriots won a minor victory over British Regulars on May 26th, 1777, in Middletown, according to the Pennsylvania Journal. On that date Patriots under the command of Gen. Benjamin Lincoln give the enemy “a pretty little threshing.” In the fighting the British lost seven men and three horses. The Americans suffered three wounded, one mortally.

A Loyalist Ambush at the Local Tavern

In September of 1779 a skirmish occurred in Shrewsbury that has come to be known as the Allen House Massacre. Approximately 12 Continental soldiers from Virginia were stationed at Allen House, which was then operating as the Blue Ball Tavern.

Stagecoaches and riders would stop to feed and water their horses as well as their passengers at the Blue Ball, and other taverns across New Jersey. At the time, the Blue Ball was considered to be the most notable tavern in Shrewsbury.

During this era New Jersey had a law on the books that required towns to offer a place where travelers could rest and find sustenance, to help facilitate growth within the settlements and foster trade and commercial opportunities. The result was a network of taverns on major roads roughly 6-8 miles apart throughout most of Monmouth County. Taverns were an essential part of public life in colonial America and the Blue Ball was a typical example.

It was common in England as well as America to give taverns colorful names that would stand out and be remembered by the public. The Blue Ball Tavern is an excellent example of this tradition. Taverns often had names that could be used as symbols on signs for those who could not read or did not understand English. Taverns in New Jersey were known as White Horse Tavern, Red Ball Tavern, etc. A traveler needed only to be able to know that when they saw the sign with the Blue Ball, that meant they were in Shrewsbury and could either rest there or expect to travel another 6-8 miles to reach the next such house of hospitality.

The building that was the Blue Ball Tavern was built in 1710 by carpenter/architect Judah Allen (a Massachusetts-born Quaker). It incorporates early Dutch influences in its construction and architectural style. It was originally the second home of Richard Stillwell, a wealthy New York merchant, his wife Mercy, and their eight children. The building was purchased by Josiah Halsted in 1754 who then converted it into a tavern.

During the 1700s and into the early 1800s it continued to operate mostly as a tavern. These gathering places were not simply a place to drink alcohol, they were the cornerstone of public life in colonial America. They were where you heard local and national news. People would come to taverns to discuss politics, business, and just about everything else in the 18th century. It was also the place to come and hear live music, eat a hearty meal and dance. Public meetings and elections were often held in taverns. They were often where traveling circuit judges periodically held court, as was the case with Allen House. And of course, they served as hotels or inns for weary travelers.

Men typically had to share beds with other men (strangers) sleeping head to toe in an upstairs tavern bed. And boarding a horse cost more than a bed for the night.

Halstead added a kitchen wing with a large beehive oven to the building and added a second floor as well. Halstead was very successful for a time but sadly fell into debt and then debtor’s prison. Still, the structure would see many changes over the years. For a while it operated as a doctor’s office and residence. Dr. Edmund Allen (no known relation to Josiah Allen) used the building as his medical practice throughout the early 1800s. The house also served as a meeting place for the Vestry of Christ Church as well as the Shrewsbury Library.

The War Comes to the Blue Ball Tavern

When fighting first broke out between the colonists and the British in 1775, the Continental Army soldiers were considered a foreign occupying force in the eyes of many local Loyalists. They were men from another state there to put down the local insurgency and stop the locals from continuing to trade with British. Being from Virginia, these soldiers would not have familial ties to the locals and would have had no reason to overlook such illegal activities. These Virginians belonged to Col. Benjamin Ford’s Regiment.

According to a local man named Lyttleton White, who wrote to Rev. Daniel Veech McKean in 1846, a group of Loyalists ambushed Ford’s squadron of Continental Army soldiers staying at the Blue Ball. On June 13, 1779, a party of five Loyalists or “Refugees,” led by Joseph Price and Richard Lippincott, traveled by boat down the Shrewsbury River and through the woods until they reached the Anglican Church at the intersection with the Blue Ball Tavern. They hid behind the gravestones in the church graveyard until they were ready and then charged the Blue Ball Tavern with bayonets fixed.

They burst through the door and took the Virginia Continentals completely by surprise. One raider managed to grab the muskets of the Virginians, which were stored together, leaving the Continentals essentially unarmed. A brief melee ensued but ultimately the Lieutenant in charge of the Continentals surrendered due to his men not having weapons to fight with – but not before three of his men were bayonetted who ultimately died of their wounds. One fell dead immediately. One ran down King’s Highway, what is today Broad Street, to Red Bank, where he finally fell and died from his wounds. The third fled on what is today Sycamore Avenue to Tinton Falls, where he too finally fell and died. The remaining soldiers were taken prisoner.

In that era, that usually meant being taken to Manhattan and deposited either in one of the prisons made out of former sugar warehouses, or in the dreaded British prison ships, former seagoing vessels stripped of everything save a hull and deck. Portholes were sealed up, and conditions were beyond inhuman. Most of those sent to British prisons during the war never returned.

Meanwhile, the ongoing acts of vengeance and retribution would continue in this manner until the very end of the war.

Eventually, the house that once was the Blue Ball Tavern was donated to the Monmouth County Historical Association, which restored it to appear as taverns did during the Revolutionary War era. Allen House Tavern is a now a museum, open to the public during the warm weather season.

About the Author

William Gardell is a former educator and an amateur historian who earned a master’s in history from Liberty University. He is a veteran service officer in Monmouth County, NJ where he lives with his 2 young children. William also is currently serving in the US Coast Guard Reserve as a First Class Petty Officer and as a volunteer firefighter in Middletown, NJ.

Sources:

Adelberg, Michael. (2013). The Forgotten First Battle of Monmouth. Journal of the American Revolution. Available: https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/05/the-forgotten-first-battle-of-monmouth/.

Allen House. (2009). Revolutionary War Sites In Shrewsbury, New Jersey. Revolutionary War New Jersey. Available: https://www.revolutionarywarnewjersey.com/index.htm.

Allen House, c. 1710. (2024). Our Historic Houses. Monmouth County Historical Association. Available: https://www.monmouthhistory.org/historic-houses.

Allen House. (2024). Monmouth County’s Historic Sites. Monmouth County NJ Tourism. Available: https://tourism.visitmonmouth.com/historical-sites/

Bound Brook, May 29. (1777). The Pennsylvania Journal, or, Weekly Advertiser, Wednesday, June 4, 1777, P. 2.

Stryker, William, editor (1901). New Jersey Archives, Second Series, Vol. 1, Newspaper Extracts Vol. 1, 1776-1777. John L. Murphy Publishers, Trenton, N.J.

White, Lyttleton. (1846). Letter to Rev. Daniel Veech McLean dated March 25th, 1846. Published in: Phillps, Helen C. (1977). Red Bank on the Navesink. Caesarea Press, Red Bank, N.J., P. 27.

Zaorski, William J. (1972). Monmouth…a page in history. Monmouth County Department of Public Information, Monmouth County Board of Chosen Freeholders, Freehold, N.J.

Such interesting background to places we pass every day. I wonder about a house that may have been called “The Wayside Inn” at the intersection of Wayside Rd and Green Grove Rd in the Wayside area. It stands today, and I was told it was one such tavern and inn.

There was a very famous Wayside Inn outside Boston known as the oldest tavern in the US, and made famous by poet Henry Longfellow. At one time this Wayside Inn was owned by Henry Ford.

Perhaps this fame is why there have been a number of taverns in Monmouth County called Wayside Inn. For example, there was a Wayside Inn on Union Avenue in Brielle which closed in 1920. There was another Wayside Inn on Route 33 near Freehold. In 1910 a different Wayside Inn opened in Asbury Park at 516 First Ave., and another opened on Neptune Highway. More recently there was a Wayside Inn operating in Tinton Falls in 1983.

The phrase “wayside inn” is also commonly used generically to describe roadside taverns, and so it is very possible that the tavern you’re describing by Green Grove Road may have been called a wayside tavern, but may not have been named Wayside Tavern.