On June 26, 1778, British troops, under the command of Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton, first arrived in Monmouth Court House, now known as Freehold Township. With France entering the American Revolution on the side of the Patriots, the British wanted to consolidate their forces within their strongholds in New York City and in the southern states, and so had evacuated Philadelphia on June 18, 1778. Wealthy Loyalists and officers’ families traveled by Royal Navy ships, leaving Clinton’s army to then march on foot across enemy territory in New Jersey to reach safety.

General Clinton’s army, 12,000 strong, included many kinds of units in addition to regular British Army redcoats; American Loyalists who were fighting for the king comprised numerous groups. For example, Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe led the Queen’s American Rangers, which included the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of New Jersey Volunteers, as well as Lt. Col. John Van Dyke’s New Jersey Volunteers unit. Clinton’s army also included a unit of 49 freed American slaves called the Black Pioneers who served as woodcutters and bridge builders to help the British make their way across mostly rural central New Jersey.

Some members of these Loyalist units fighting for the king were former residents of Monmouth County. In the months after fighting broke out between Americans and the British in 1776, Patriots and Loyalists in Monmouth County took turns confiscating property, conducting raids, and clashing in every way possible. Freehold initially had a number of prominent and active Loyalists among its residents who briefly controlled the village. Continental Army troops eventually broke up the Loyalists in the area, forcing many to flee to Sandy Hook, which the British controlled for the entirety of the Revolution. The area around the Sandy Hook Lighthouse was a tent city that became known as Refugeetown. Former wealthy landowners and ordinary townspeople alike lived there, as did runaway slaves, Continental Army deserters, and their families.

Clinton’s men, having evacuated Philadelphia, proceeded through Haddonfield, Mount Holly, and Moorestown before reaching Allentown in Monmouth County on June 24. The following day they headed to Freehold.

The British had endured harsh conditions on their trek. Mosquitoes, blistering heat and humidity, constant harassment by local militia, and traversing swamps and morasses left the troops exhausted. Upon reaching the high grounds around Freehold they stopped for a brief rest in advance of the completion of their mission.

From this point, Clinton’s army was 12 miles away from the heights of Middletown–a day’s march. This high ground was essentially unassailable, and once there, the soldiers would have an easy time making the final trip down to Sandy Hook to board boats to New York.

Instead, Clinton remained in Freehold for two full days. His correspondence clearly indicates he felt the men needed rest. But he also was receiving constant intelligence and updates from Loyalists across the state who were keeping an eye on George Washington’s units as they began to converge on Freehold. Clinton had enjoyed great success against Washington in 1777, and no one on either side doubted the British were the more experienced and vastly superior fighting force.

Washington’s army, however, had spent a brutal winter at Valley Forge learning to drill as discrete units, working with artillery, and practicing proven tactics with the assistance of professional soldiers, such as Major General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, and Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, better known to Americans as the Marquis de Lafayette. After narrowly surviving the winter, followed by months of constant drilling and training, the Continentals were spoiling for a fight.

And fight they would. But in the days before that battle commenced, something else was happening. Some historians have labeled the event The Sack of Monmouth Court House.

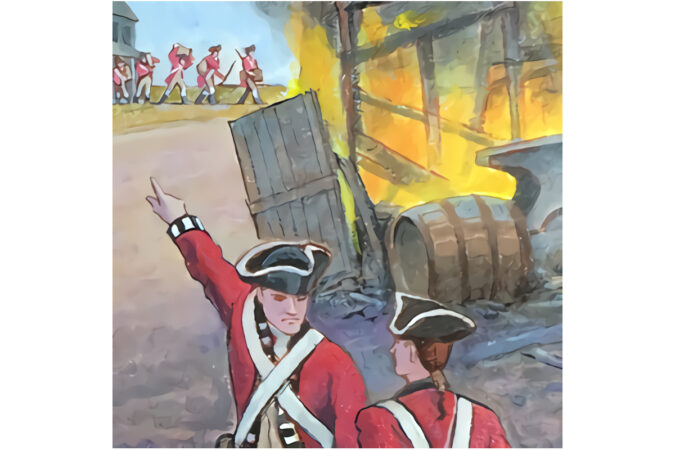

The Monmouth County Loyalists who were fighting for the king now found themselves with a unique opportunity to exact retribution upon their neighbors and countrymen for having driven them from their homes and depriving them of their property and liberty. Houses and businesses belonging to Patriots were put to the torch; women were raped; livestock and anything usable was confiscated; and fertile planting fields were salted, all in a two-day orgy of cruel and violent vengeance.

The toll of loss would have been much greater, but many Patriot families, knowing the British were headed their way, had fled their homes, driven their livestock into the woods, buried their silver in the ground, or hidden valuables in wells. Some joined up with militia units for protection; some men joined the Continental Army, believing that British soldiers would not harm innocent women and children. This proved to be a disastrous error in judgment, as the harm came not from the British, but primarily from fellow Americans.

British and Hessian generals, including Clinton, professed to be aghast at what occurred, but took no action to stop it. One Hessian officer wrote, “every place here was broken into and plundered by the…soldiers. The church, which was made of wood and had a steeple, was miserably demolished;” the soldiers were “breaking and destroying everything.”

By the end of the 27th, “11 dwellings, assorted outbuildings and at least two businesses had been burned or otherwise destroyed,” according to Mark Edward Lender and Garry Stone Wheeler in Fatal Sunday, their outstanding account of the Battle of Monmouth. Only Patriots had been targeted. Among those who lost everything were the village doctor, the blacksmith, and a tavern keeper. Villagers returning after the battle found “the earth was strewn with dead carcasses, sufficient to have produced a pestilence.”

On June 28, the two armies clashed in the day-long Battle of Monmouth, considered by many to be a standoff. That night, under the cover of darkness, Clinton’s army packed up and left Freehold. The Continentals awoke after a night spent sleeping on their muskets on the battlefield to find the enemy long gone.

Washington’s army would move on to other campaigns. No other village was sacked during the Revolution. But after that outrage, the residents of Freehold and the rest of Monmouth County turned up the heat on the escalating civil war in the region. Patriots continued confiscating and selling off Loyalist properties and arresting people without charges, assessing fines, and removing them to prisons in Pennsylvania and Maryland, often solely for their belief that America was better off under crown rule. Loyalists at Sandy Hook, and others hiding in the Pine Barrens, including former slaves such as the infamous Colonel Tye, conducted raids into Monmouth County, arresting militia leaders; stealing guns, food and ammunition; and burning and pillaging homes.

This constant retribution continued until the very end of the Revolution. It did not begin with the Sack of Monmouth Court House, but the events of June 26 and June 27 surely served to significantly escalate the volatility and violence taking place county wide.

Sources:

Adelberg, Michael S. (2010). The American Revolution in Monmouth County: The Theatre of Spoil and Destruction. The History Press, Charleston, S.C.

Lender, Mark E., & Stone, Garry W. (2016). Fatal Sunday. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla.

Smith, Samuel S. (1975). The Battle of Monmouth. Pamphlet published January 1, 1975, New Jersey Historical Commission.

Leave a Reply