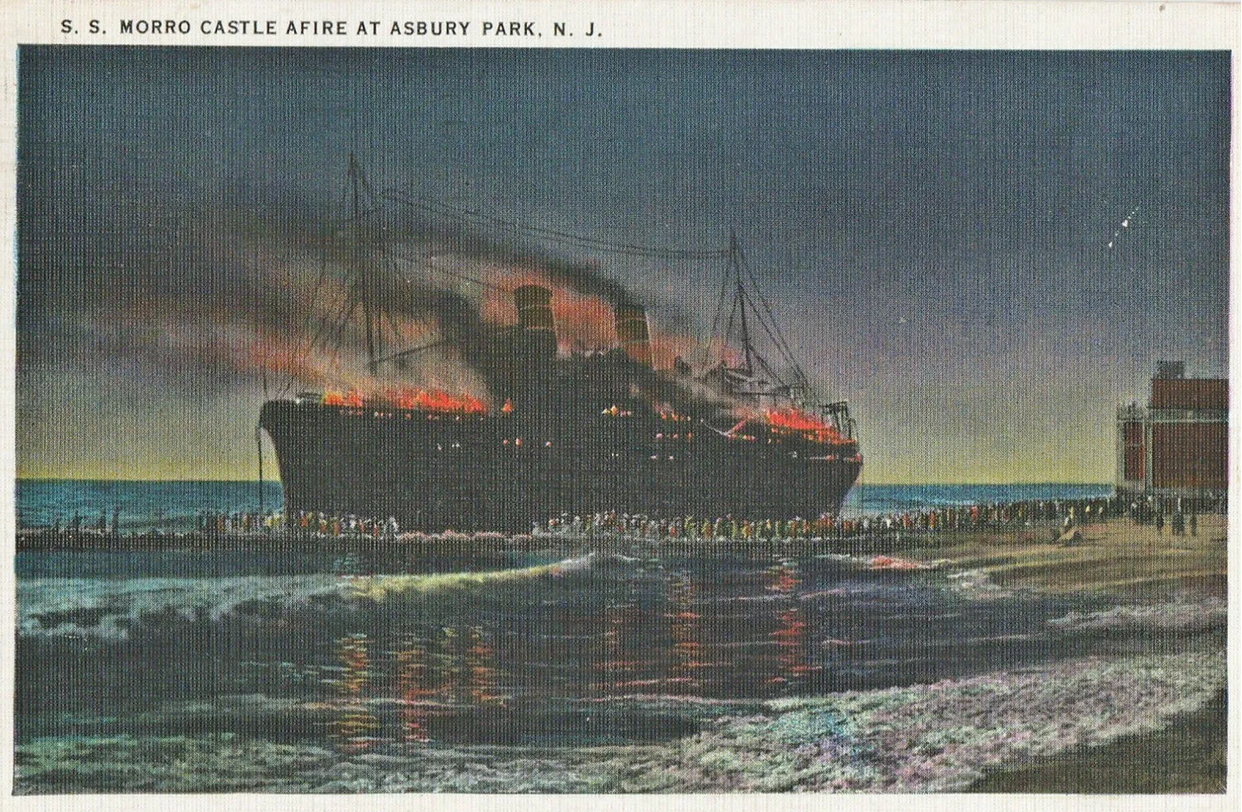

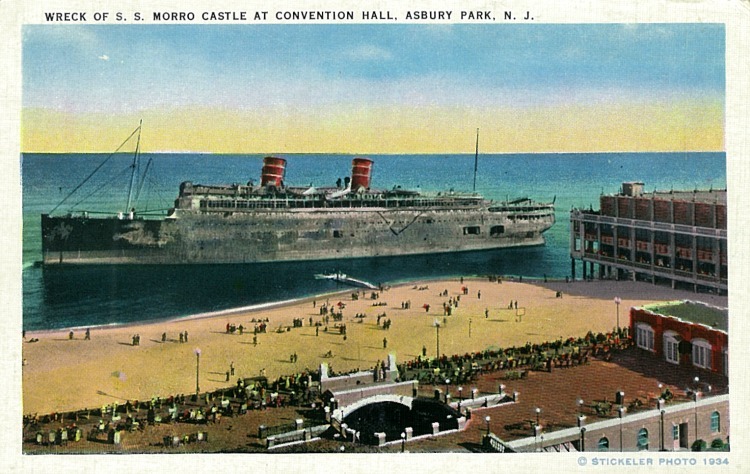

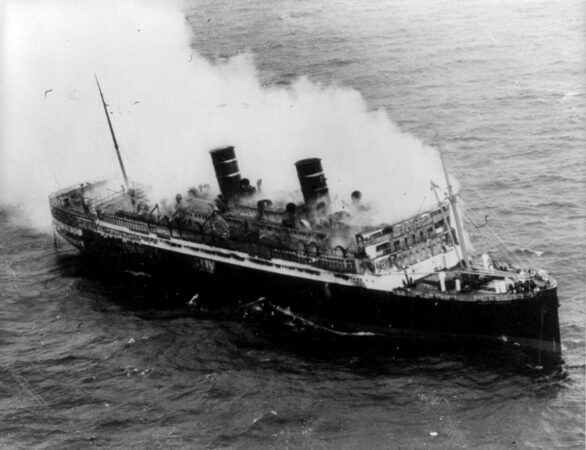

On September 8, 1934, the luxury passenger liner SS Morro Castle caught fire and burned during a raging storm off the coast of New Jersey, killing 137 passengers and crew members. The ship, en route from Havana to New York City, eventually drifted ashore at Asbury Park after a Coast Guard towline broke, and remained on the beach for several months until she was towed off and scrapped. The cause of the fire remains unknown, but most historians now believe it was arson.

The SS Morro Castle was a ship of the Ward Line, running between Havana and New York City. She was 480 feet in length and could carry 489 passengers and 240 crew. A sister ship, the SS Oriente, worked the route in the opposite direction. Transporting wealthy travelers to an exotic tropical resort destination was only one part of the Ward Line business model. The Morro Castle also carried cargo of all kinds each way, but most lucrative was the government contract to carry mail to and from Cuba on a precise schedule.

The Morro Castle came into existence during troubled times for the host nations of its ports of call of New York City and Havana. The ship was launched during the Great Depression, and during its years in service, traveled to Cuba when that nation was in a time of great political upheaval, with rebels and nationalists operating in violent and unpredictable ways.

Coming out of the Roaring Twenties, the Morro Castle seemed like a sure bet. It was during the time of Prohibition, but passengers could enjoy fully legal liquor aboard ship. Sailings featured gourmet meals, and entertainment coordinated by a cruise entertainment director. And Havana at that time was one of the most exotic cities in the world, known for hedonistic entertainment and adventurous intrigue. And yet, due to the Depression, the Morro Castle sailed on most occasions with about half as many passengers as she could carry. And although jobs were scarce, the Morro Castle also routinely sailed without a full crew.

A Catastrophic Cataclysm

The first sign of trouble was when the captain came down sick, thought by observers to have been food poisoning. Hours later, he was dead. Then, after the fire started, everything that could go wrong, did. The Chief Officer who took over after the captain died made the critical error of steering the ship into the 30-knot winds, forcing the fire to move rapidly through the ship from bow to stern. The crew used the lifeboats for themselves, or not at all. Fire extinguishers failed to work. Life preservers failed or caused injuries, as passengers jumping from upper decks were hurt by the hard cork of the preservers upon impact with the water. The Coast Guard response was delayed and ineffective. No one knew who was in charge once the ship ran aground on the beach. Evidence that might have explained what happened was destroyed by the first people to board the vessel.

The intrigue surrounding the Morro Castle disaster is the stuff of Agatha Christie novels. Virtually everyone associated with the Morro Castle came under suspicion. The captain would have been an obvious suspect, but he died under mysterious circumstances just hours before the fire started. The other officers were suspects. The crew was full of suspicious characters. Even the passengers came under scrutiny. Here are just some of the subplots investigators grappled with as they tried to determine what happened on that fateful night:

Was the captain murdered? Robert Renison Willmott was a seasoned seaman and ship’s officer who captained the Morro Castle starting with its maiden voyage, and he was at the helm for all 174 of the ship’s sailings. He was known as someone more interested with keeping the passengers happy than with troublesome details such as fire drills. He often turned smoke detectors off when the ship was carrying animal hides north from Cuba, as they gave off fumes that sometimes triggered the alarms. He insisted on having the ship’s superstructure repainted regularly, which gave the vessel a beautiful sheen, but when it caught fire, those layers of paint proved highly flammable and deadly.

Willmott had little use for the constantly-changing crew and was uninterested in their complaints about long hours, poor working conditi0ns, low pay, and illegal activities supposedly taking place aboard ship. No one knows when Willmott came to the conclusion that someone on the ship wanted to murder him, but when the Morro Castle arrived in Havana for the last time, he shared that fear with his officers. He did not say if he knew who it was that he suspected.

On the afternoon of September 7, Willmott complained of stomach pains. Hours later, the ship’s doctor sent a telegram to the Ward Line offices stating that Captain Willmott was dead as of 7:45 p.m., cause of death: “acute indigestion.” Willmott’s remains were never found, so no autopsy was performed, and the cause of his death remains unsolved.

Was the ship sabotaged by a member of the crew? The ship was routinely understaffed when she embarked, and many of the crew members were inexperienced seamen. On any given trip, about half the crew were Americans who spoke little or no Spanish, and the other half were Cubans or others from Latin America, who typically spoke little or no English. Bigotry and language barriers created an atmosphere of constant conflict and complaints about the poor working conditions. It was rumored that the Morro Castle often carried guns and ammunition south, for illegal sale to Cuban nati0nalist or rebel factions, and crew members allegedly smuggled marijuana and heroin north to the U.S.

There were clearly suspicious characters among the crew, people who may have been capable of violent sabotage. But the problem with the theory that a passenger sought to sabotage a ship while at sea is that person has no better chance of survival than the intended victims. It would be almost suicidal. Who would take that kind of risk, and why?

Was the ship sabotaged by one of the passengers? People on opposing sides of the political upheaval in Cuba traveled to and from the U.S. aboard the Morro Castle on the same sailings, and someone may have seen an opportunity to eliminate a key leader or contributor to the opposing side. It was also rumored that the Morro Castle regularly had stowaways or illegal passengers aboard, people seeking asylum in the U.S., or escaping persecution in Cuba. After the disaster of September 8, 17 of the bodies of those who died were never identified or claimed, so we do not know even know for certain who was aboard the ship on that trip. But no evidence was ever found to support the theory that a passenger may have been involved.

The radioman did it. The radio operators aboard the Ward Line ships were not crew members, nor were they employees of the Ward Line. They were employees of an independent company that provided certified radio operators to shipping companies. Three men were aboard the Morro Castle on September 8 as radio operators. Even just this small group struggled with their own dramas and problems. One of the three was considered an agitator, someone who constantly harped about working conditions and complained to the ship’s officers about every little thing. This man was to have been replaced upon arriving in New York City, and so he was among the immediate suspects for having had a motive to sabotage the ship.

The man on duty in the radio room that night was George Rogers. Unbeknownst to anyone at the Ward Line, Rogers had lived a life of juvenile delinquency, sexual deviance and assorted crimes throughout his life. And wherever George Rogers was, suspicious fires tended to occur. In those days, companies like the Ward Line and the company that provided radio operators made no effort to vet potential employees.

Rogers was throughout his life a surly and unlikable person by all accounts, including his wife. On board the Morro Castle, he liked to play the other radio operators against one another, creating stress and arguments, which he then used to position himself to ship’s officers as the superior man. They didn’t like him either.

After the fire was detected, Rogers sought permission to issue an SOS signal, as per standard procedure. Only the captain could approve an SOS signal. But the captain was dead, and the ship’s officer who assumed control proved to be overwhelmed by the enormity of the gale-force storm that buffeted the huge ship as the fire burned out of control. Eventually, Rogers issued the SOS signal without permission. Even while suffering serious burns, Rogers remained at his station, sending out SOS signals. He would be among the last survivors taken from the ship. In the days immediately following the disaster, he was heralded as a hero, and was of such a celebrity status that he was booked for a tour of vaudeville theaters, where he regaled audiences with the “real” story of what happened to the Morro Castle. Sadly, accounts about what happened on September 8 began to tell a different story, and people quickly tired of Rogers, and the tour was cancelled.

In 1938, Rogers worked for a Bayonne Police Department official, installing radios on squad cars. Rogers revealed his fascination with incendiary fuses and timing devices, and said that the fire aboard the Morro Castle had been started with a timing device hidden in a pen in a waiter’s coat in a locker. The police officer knew this was information that had never come to light before, and he informed his superiors. Rogers responded by attempting to murder the officer using a firebomb with a timer hidden in a fish tank water pump. He was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 12 to 20 years in Trenton State Prison, but he was set free after only four years, accepting an offer to join the military during World War II, when experienced radiomen were urgently needed.

Years later, Rogers found himself back at Trenton State Prison after being convicted of murdering his neighbors whom he had bilked in an investment scam. He died in prison proclaiming his innocence and never admitted any guilt or culpability regarding the Morro Castle.

Historians succeeded in obtaining FBI and other government records for George Rogers in 1999, but many of the files are heavily redacted or illegible. To this day, the U.S. government continues to keep information about George Rogers secret. Some have speculated that he became some sort of informant, but he remains mostly a mystery.

The question arises once again, why would George Rogers sabotage a ship, knowing that his chances of survival were no better than anyone else’s? Why not use one of his timing devices to create a fire after he was safely away? Here, the opinions of experts on arsonists tend to agree that people who are obsessed with starting fires often fail to consider their own safety when following their urges, and often after the fire is set, become passive and just watch things unfold.

The investigation ultimately concluded that the fire started in a locker in a room used by passengers for writing letters. The cause was determined to be either arson, or spontaneous combustion.

The Morro Castle was built according to the most modern standards for safety, and had passed all safety inspections. Much of her design was informed by lessons from previous disasters like the RMS Titanic. And yet after the fire, experts realized that standards and practices for fire safety on passenger ships was still woefully inadequate. New regulations emerged from the Morro Castle disaster that made traveling by sea much safer to this day.

Many unanswered questions remain: What caused the death of the captain, just hours before the fire? Why weren’t all the lifeboats used? Was George Rogers a hero, or a villain, possibly responsible for starting the fire in the first place? And why does the U.S. government continue to keep facts about George Rogers secret after all these years?

Sources:

Burton, Hal. (1973). The Morro Castle: Tragedy at Sea. The Viking Press, New York, N.Y.

Coyle, Gretchen F., & Whitcraft, Deborah C. (2012). Inferno at Sea: Stories of Death and Survival Aboard the Morro Castle. Down The Shore Publishing, West Creek, N.J.

Gallagher, Thomas. (1959). Fire at Sea: The Story of the Morro Castle. Rinehart & Company, New York, N.Y.

The Morro Castle Remembered. (1984). Press Staff Report, Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., September 9, 1984, P. I-8.

Thomas, Gordon, & Morgan-Witts, Max. (1972). Shipwreck: The Strange Fate of the Morro Castle. Stein & Day, Inc., New York, N.Y.

Image Credit: International News Photos, Inc. – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3b14818.

Morro Castle postcard scans: Public domain.

As you noted, fire drills were unheard of aboard this ship. So were lifeboat drills. Capt. Willmott’s insistence on constant repainting had gummed up the davits so badly that many boats were unusable.

As to whether Willmott’s remains were found or removed from the wreck, sources differ. Apparently there wasn’t enough left of the body to permit an autopsy.

Dislike of the skipper was widespread among the crew, and it’s far from impossible someone might have poisoned his food or drink. But I don’t think it was Rogers, who encouraged Willmott’s suspicion of sparks George Alagna so Rogers would be promoted to chief radioman.

Rogers, unliked and unlikable, clearly had a desire to make himself some kind of hero. Why, then, did he refuse to send a distress message until ok’d by the hopelessly overwhelmed CO Warms? Did he underestimate the extent of the fire? Or was the firebug in him determined to let things get really bad before the would-be hero in him took over?

And what of those heavily redacted federal files? Was Rogers an FBI informant, and if so, did he hope to play hero on a national scale – either for the US or for Cuba? It is confusing but tempting to speculate what sort of secrets about George Rogers might still be considered incriminating 60-70 years later – and to whom.

Prescient observations and valid questions all. The many mysteries of the SS Morro Castle are likely to be a subject of fascination and speculation for many years to come. I’m surprised you didn’t bring up the curious aspect of the USS Tampa, the USCG ship that essentially chose to stand by and not offer assistance nor attempt to try and avoid the ship grounding on shore. The radio messages are a matter of public record, the Tampa stood down and was never called out for it.

Correction: It is not the SS Titanic, it is actually the RMS Titanic.

Good catch! It has been fixed, thanks!