On November 8, 1775, a 22-year-old slave named Titus ran away from his owner and master, John Corlies of Colts Neck. Corlies was a Quaker who did not agree with Monmouth County Quaker views on the handling of slaves. Quakers during this period thought slaves should be taught to read and write, and set free at age 21. Corlies did none of these things, and was known to be hard on his slaves, not sparing the whip. Ultimately, the Quakers would revoke Corlies’ membership because of his handling of slaves.

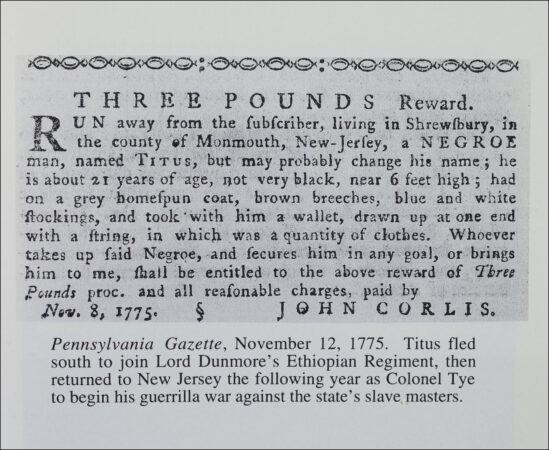

On November 12, 1775, Corlies placed an ad in the Pennsylvania Gazette (see image above), offering a reward for the return of Titus. This was common practice at the time, and surviving newspapers of the early 18th century are filled with accounts of servants and slaves running away, with rewards offered for their return.

The day before Titus escaped, November 7, 1775, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore and royal governor of Virginia, had declared martial law, and promised freedom for American slaves and indentured servants who left their owners to join the royal forces. This triggered a flood of escapes and runaway slaves, which angered slaveowners, both Patriot and Loyalist. Dunmore’s Proclamation stated in part that, “all indentured servants, Negroes, or others…be free that are able and willing to bear arms.” Dunmore believed that the fear of losing precious slaves would provide incentive for colonists to abandon the pursuit of independence, in addition to adding badly needed men to his small army of 300.

The day after Dunmore’s Proclamation was issued, Titus ran away from Corlies. While news of Dunmore’s offer traveled very quickly, historians believe that Titus could not have known about the offer at the time he ran away. Titus’ decision to flee hinged on a combination of local factors. He surely had observed the Quakers’ failed attempts to convince Corlies to free his slaves. He no doubt was also aware that his recent 21st birthday marked the age at which nearby Quakers freed their slaves. He may also have been alienated by Corlies’ refusal to educate his slaves at a time when Quakers were encouraging such programs.

At the same time, rumors of the formation of a slave regiment had been coming out of Virginia for months, and so it is also possible that Titus anticipated Lord Dunmore’s offer; it is also possible that if convinced that the British were going to make an offer to slaves, slaveowners would take precautions to prevent runaways, and Titus saw the chance to leave before that could happen.

Titus made his way to Virginia and joined Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment, now calling himself simply “Tye.” He had escaped, and re-invented himself, and was now a soldier in an all-Black regiment, fighting against the slave-owners who had mistreated him so badly. He would go on to distinguish himself in battle time and again.

Sources:

Allen, Thomas B. (2010). Tories: Fighting for the King in America’s First Civil War. HarperCollins, New York, N.Y. P. 316-320.

Hodges, Russell Graham (1997). Slavery and Freedom in the Rural North: African Americans in Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1665-1865. A Madison House Book, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Md., P. 91-107.

Adelberg, Michael S. (2010). The American Revolution in Monmouth County. The History Press, Charleston, S.C., P. 75-97.

Leave a Reply