Either the Barnegat Pirates are the most infamous scoundrels upon the face of the earth,

or they are a much injured set of men.

New Jersey State Senator Alexander Wurts of Hunterdon County,

in a resolution adopted by the senate on February 28, 1846.

On January 6, 1832, the ship George Canning from Liverpool, carrying dry goods and hardware, wrecked on Absecon Beach. The captain and passengers were taken off by a vessel bound into Egg Harbor; several days later, newspapers reported that cargo from the Canning had been saved and brought to New York City.

News coverage of the Canning wreck was consistent with newspaper coverage of shipwrecks going back to the dawn of newspapers. There was nothing in those reports to indicate there was anything amiss.

But two years later, out of nowhere, a major New York City newspaper accused the residents of Monmouth County of heinous crimes relating to the Canning and three other shipwrecks. They were called “wreckers,” and much worse. Despite the high probability the accusatory story was a hoax, the people of Barnegat were labeled as land pirates, and would be smeared in this fashion for decades. Even a governor’s special investigation, which not only exonerated the Monmouth County coastal residents, but extolled the courage and selflessness with which they rendered aid to ships in trouble, failed to remove the taint of land piracy.

This Timeline examines the following questions:

- What – or rather, who – were the wreckers of Monmouth County?

- How did they differ from their counterparts in other shipwreck-prone areas of the world?

- How did they end up with such a terrible reputation?

- How did the wreckers of Monmouth County influence the formation of the U.S. Coast Guard?

What – or Who – are “Wreckers?”

Today, if you are at sea in United States territorial waters, and in trouble, you have the U.S. Coast Guard as a formidable resource for assistance. Prior to the formation of the Coast Guard, there were three services assisting navigators: The U.S. Lighthouse Service, which operated lighthouses and maintained navigation aids such as buoys and channel markers; the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, which served as the seagoing law enforcement and rescue branch; and the U.S. Life-Saving Service, which rendered assistance from land to ships foundering close to shore. Before these federally funded organized services were established, assistance to distressed vessels close to shore was handled by locals, mostly volunteers, who ran the gamut from altruists to opportunists, and from the charitable to the outright criminal.

There are many tales of men and women of Monmouth County coming to the aid of endangered ships over the years, and risking their own lives to try to help save those on board. These people faced grave dangers in order to rescue passengers, crew, cargoes, and even ships, that could be refitted by their owners to sail again. Their stories are marked by courage and resolve.

In newspapers in New York City and Philadelphia, however, these coastal residents eventually became branded as ruffians, thieves and even corpse-robbers. They were accused of using “trick and device” to lure navigators into reefs or shallow waters to induce a shipwreck, and then plunder the vessel and any of its occupants, alive or dead. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer:

When the sea was roughest and the nights darkest, and mariners were carefully feeling their way along that naturally dangerous bit of coast, those ruffians showed false lights and so lured the ships into the breakers and on to their destruction…These people…care nothing what precious lives were lost, what property was sacrificed.

Acclaimed novelist John Fowles, author of the nonfiction book Shipwreck, about the wreckers of the Scilly Islands and Cornwall in the United Kingdom, wrote:

…every sailor wrecked on these coasts knew he had two ordeals to survive: the sea and the men on shore, with little likelihood that the second would be kinder than the first.

Such harsh sentiments were likewise applied to the wreckers of Monmouth County. These accusations have been so pervasive for so long that they form the dictionary and thesaurus results for the word “wrecker:” Destroyer, ruiner, plunderer, demolisher, mutilator. But is this accurate?

A Maritime Tradition for Millennia

For thousands of years, oceangoing cargo transport was conducted via sailing ships, and throughout the era of sail, ships, captains, passengers, and crews faced all manner of risks and dangers. Any number of factors could lead to a ship being in danger or distress, such as running aground on unseen sandbars; crashing into rocks just below the surface; cargo shifting in the hold; or taking on water from leaks in old rotting hull timbers. Inexperienced navigators, cartographical errors, poorly built ships, sudden storms, pirates and privateers, warring navies…it seems something of a miracle any voyage was ever safely concluded.

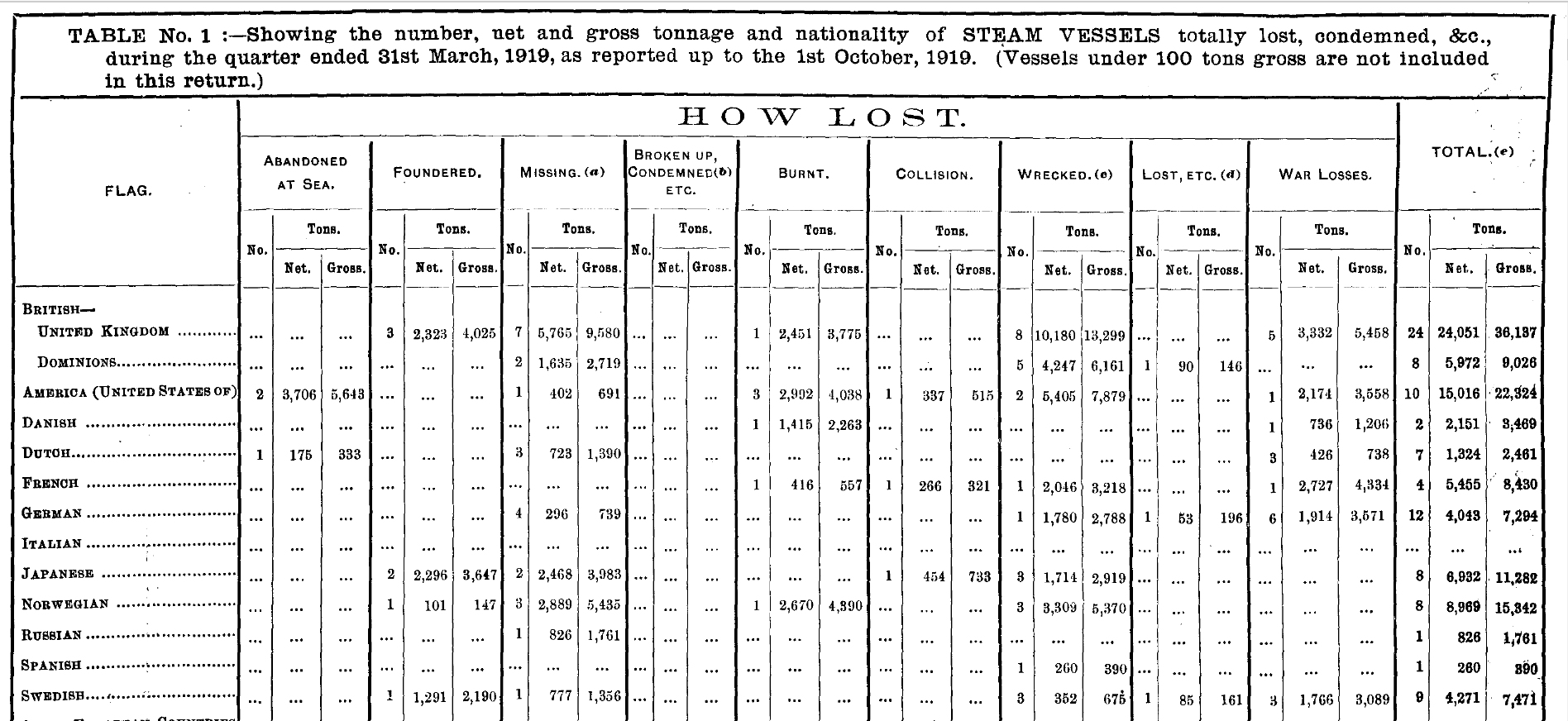

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping published reports on the various losses of ships at sea. A report from 1890 tracked losses across the following categories: Abandoned at Sea; Broken Up, Condemned, etc.; Burnt; Collision; Foundered; Lost, etc.; Missing; and, Wrecked. “Missing” ships were those that had failed to reach their destination and had not been seen, while “Lost” ships were those for which there was simply no information available. What these classifications demonstrate is the enormous risk of going to sea at that time.

When in trouble, and in proximity to shore, ships’ crews depended on those on land for assistance. In populated areas such as the entrances to New York Harbor, ships and manpower resources were available to render assistance, often with wreck-masters appointed by local authorities to cover certain stretches of coastline. In remote places, rescue depended on whether anyone was even aware of the distressed vessel, and if so, their desire – and ability – to render aid, either for humanitarian reasons or for the promise of reward.

Coastal areas like Cornwall and the Florida Keys, at the far ends of land, tended to be impoverished communities during the Age of Sail, so when a ship came into view that appeared to be in trouble, this meant potentially good fortune for those on land. Goods, supplies, livestock, slaves, any kind of cargo could be the equivalent of “found money.” Some shipwrecks were just that: sunken Spanish galleons loaded with gold and silver that were salvaged by free-diving indigenous people. Even the sails, ropes, brass fittings and wood from a ship could be salvaged.

The basic concept of “wrecking” was established over centuries by formal regulation as well as by maritime tradition. Either way, the way it was supposed to work was as follows: locals rendered assistance as practicable, and were then entitled to divide up and keep or sell certain things salvaged from a wreck.

In the Caribbean and along the Florida Keys, wreckers were independent competitors. With multiple parties of wreckers competing to salvage wrecks, maritime law and tradition held that whomever was first to reach and board the vessel became the “wreck-master.” In more populous places like Monmouth County, wreck-masters were appointed as local government employees and paid to cover certain areas of coast and supervise the rendering of assistance – but were given no training, poor equipment, and few resources of any kind.

The wreck-master coordinated available resources to salvage a vessel, including rival wreckers and local volunteers, and was responsible for protecting and cataloging goods and people saved, for processing claims before the admiralty court, if necessary, and the allocation of rewards. The ship’s owners could recover the vessel, if salvageable, and some of their cargo, both of which were often insured to some extent. It was intended to be a synergistic approach. In reality, it often was not.

When a ship came too close to a dangerous shoreline in heavy weather, locals gathered on the beach and followed the ship’s progress, sometimes for days. This certainly happened in Monmouth County. When the foundering ship finally stopped moving, wreckers then tried to rescue and salvage what they could. In the Florida Keys, wreckers anchored their ships in safe harbors and went out each morning to see what vessels had foundered on the 200-mile reef overnight. The boatmen of Cornwall were considered to be among the world’s best at fearlessly using rowboats to board distressed vessels abandoned by their crews. The surfmen of New Jersey had long mastered the ability to launch fishing boats from shore into heavy seas. These were the kind of people who responded when ships were in trouble.

Saints or Sinners?

Over hundreds of years, all around the world, wreckers were repeatedly accused of three crimes: inducing shipwrecks; robbing survivors – or failing to make sufficient efforts to keep survivors alive – and plundering cargo:

Inducement: Locals were alleged to have lit bonfires on beaches or cliffs to create the appearance of harbor entrance-markers. Other stories held that locals hung lanterns around necks of livestock, whose movements would be seen from far out at sea as signaling ships at anchor in a safe harbor. There are also stories from the Caribbean where wreckers extinguished bonfires intended as warning signals, when the wind promised to blow ships onto the reefs.

Despite the enduring nature of these accusations, there are in fact no documented cases of inducement by wreckers. One historian examined all the salvage cases brought before the admiralty court in Key West, and noted that not one ship captain ever claimed to have been induced into a wreck.

Treatment of Survivors: In the U.K., an early and short-lived law established that land-based salvagers could lay claim to anything on a wrecked vessel so long as there were no survivors on the ship. Even one surviving crew member or passenger triggered an entirely different set of rules, making it more difficult for salvagers to keep what they could save. These laws were repealed fairly quickly, but this was still the mindset of the Cornwall and Scilly Island wreckers for many years, and this assumption migrated to the wreckers of the British colonies over time.

Stories emerged of crew members who had abandoned ship and made it to shore, only to be met by land-based wreckers with clubs and fists. Some stories told of survivors who had made it to shore in a lifeboat, only to be put back out to sea and set adrift by wreckers who could then claim that the ship had been found deserted.

As with inducements, there are no documented cases of violence against survivors on the part of wreckers. There are stories about ships foundering close to shore in raging storms in which those on shore believed rescue attempts to be suicidal, while those aboard the distressed vessel thought those on land simply needed more gumption, or merely the inclination, to render aid. Those on shore rarely received the benefit of the doubt in those situations. But this is not the same thing as failing to render aid to those who did make it to shore alive.

Plundering Cargo: Long before colonial times, at the behest of merchants, ship captains, and insurers, admiralty law regulations were adopted in the U.K. to codify the system of marine salvage such that all parties were protected and able to benefit. From this, the different types of material or goods that could be salvaged became categorized: flotsam, that which is found floating in the water; jetsam, that which has washed up on the beach; and lagan, that which lies on the ocean floor. Different laws came into existence regulating when and how people on land could stake a legitimate claim to that which they had salvaged.

People living in economically marginalized coastal communities, however, often were either wholly unaware, or else they paid little heed, to regulations governing marine salvage. When your family is starving, and the government doesn’t care, and food and valuables literally wash up at your feet, the finer points of the law don’t always come into consideration.

And so, alas, this accusation probably turned out to be true.

A Wee Bit about Admiralty Law and Marine Salvage

While it sounds like anarchy, in fact, wrecking has almost always been subject to regulations to protect ship owners, insurers, captains, crews (the interests of captain and crew were not always the same), passengers, cargo, and those who engaged in marine salvage.

According to Justia, admiralty law, or maritime law:

Regulates shipping, navigation, commerce, towage, recreational boating, and piracy by private entities on domestic and international waters. It covers both natural and man-made navigable waters, such as rivers and canals. It also covers persons and contracts related to maritime activities, such as seamen, shipping insurance contracts and maritime liens.

Admiralty laws have been in existence almost as long as seaborne commerce, with earliest citations around 900 C.E. In the U.S., maritime law evolved from British admiralty courts, which were present in most of the American colonies and functioned separately from courts of law and equity. Because these admiralty courts did not include trial by jury, the British used them to enforce things like the unpopular Stamp Act, and thus they were a factor in precipitating the American Revolution. Several figures central to the American Revolution practiced admiralty law, including Alexander Hamilton in New York and John Adams in Massachusetts.

Laws may have existed, but in an era where more people were illiterate than not, in the years before newspapers, dwelling in far-flung parts of the world, laws were not always followed, sometimes out of ignorance – and sometimes out of pure disregard for authority.

Wreckers in the American Colonies

There were five primary wrecking regions along the Atlantic coast of North America: Sable Island, 150 miles southeast of Halifax; Cape Cod and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket; the entrances to New York Harbor, including Long Island Sound and the Jersey Shore; the Carolina Outer Banks; and the sea lanes north of Cuba, i.e., the Straits of Florida, to the north and west, along the Keys, and the passages west of The Bahamas extending from the Caribbean to the mainland U.S. Wreckers operated in each of these regions, with the Florida Keys/Bahamas region being by far the most fraught with shipwrecks. Bermuda is another region famous for shipwrecks.

The earliest newspapers in the American colonies all gave great space to coverage of maritime activities, including the comings and goings of ships from local ports; reports of privateers or pirates operating in the area; news of ships that foundered or wrecked; and the activities of wreckers.

Newspapers in the U.K. from the earliest times described residents of the coastal communities where wreckers worked as among the most rapacious and vile on earth. Inhabitants were portrayed as mean and miserable people who wished and prayed for ships to wreck, hoping for a total loss of life, so as to enable their plundering. They were accused of creating inducements, of murdering survivors, and of stealing cargo. Eventually, stories emerged that told of pitched battles waged on the beach between locals hoping to obtain some flotsam or jetsam, and soldiers or constables or other locals seeking to protect the vessel on behalf of its owners. The people of Cornwall in particular were a target of severe rancor for decades.

Over time, the notion of wreckers as remorseless lowlifes became the simile of choice for British opinion writers. Corrupt politicians, crooked bankers, feeble governments, anyone to be smeared as the worst example of humanity was said to be like the wreckers.

Meanwhile, in the American colonies, a different narrative was emerging. Wreckers operating primarily around Bermuda, The Bahamas, and the Florida Keys were the subject of mostly very small news briefs of this sort:

The Snow Indian Trader, Thomas McMin, Master, from Georgia for Jamaica, was cast-away on the 10th of September, on a Reef of Rocks near the Grand Caicos (one of the Bahama Islands) where the Captain, Passengers and Crew happily got on shore, and were treated with great Humanity by some Wreckers, who afterwards carried them to Providence (referring to the island of New Providence in The Bahamas).

Positive stories about wreckers tended to speak in terms of “saving” cargo and passengers and crew, as well as helping beached vessels “get off,” meaning, pulling them off sandbars or reefs where they can be repaired or salvaged.

Typical negative news stories about wreckers described situations in which the ship’s captain attempted to retain control over his vessel and cargo after it wrecked. Some wreckers were willing to negotiate with captains in these circumstances, others were not. In those instances, the wreckers were portrayed negatively, but not nearly with the same level of vituperation as in the U.K.

The oldest surviving reference to wreckers we could find in an American newspaper dates to 1760: “Captain Garrett, belonging to the Jerseys, was cast away on Heneago, but got off by the Wreckers, and brought to Providence.” The reference to “Jerseys” dates to when the colony was divided into East Jersey and West Jersey.

Most of these stories have very few details, and are based almost exclusively on hearsay, but they describe successful rescues under difficult circumstances, casting few aspersions. For example, in 1789, in coverage of maritime news from the Caribbean, wreckers helped save the captain and two crew members of the brig Bell, of Glasgow, after a lightning strike killed 11 sailors instantly, and the ship sinking not long after.

But over time, the stories in the British newspapers planted the idea among American writers to use wreckers as an analogy for evil greed and rapaciousness. These stories never had anything to do with an actual ship or wrecker, but they had the effect of smearing coastal residents who plied that trade.

The first newspaper story about wreckers in New Jersey is believed to be from the New York Evening Post in 1816. The brig Perseverance, headed for New York City from Canada, was blown many miles off course and struck a reef off Cape May. At daybreak, the surf was too strong for rescue efforts. The ship began to break apart, and its cargo began to float ashore, where a crowd gathered and began collecting the flotsam and jetsam and absconding with it. The ship lay just 30 yards from the beach, but locals refused to try and launch a rescue boat. The captain offered his watch as reward for any boat that would come to their aid, but found no takers. The captain attempted to swim to shore, but only feet from safety was swamped by a wave and “not been seen since.” Crew and passengers tied themselves to the rigging. After two days, three sailors made a raft and reached the shore. Seven people died. “The conduct of a part of the people of Cape May County has been most infamous in plundering and carrying off the goods that were washed ashore; a lady who was drowned and whose body came on shore was stripped of her watch necklace and other trinkets; and the amount of goods stolen probably amounts to $20,000.”

The Barnegat Pirates

On December 29, 1834, the New-York Gazette and Advertiser ran a front-page story headlined “Capture of Land Pirates,” that accused the locals of Monmouth County of inducing shipwrecks, murdering crews, and plundering cargo. The story alleged that two-thirds of the residents around Barnegat were involved in these crimes and that the criminals were ultimately either brought to justice or chased away for good. The article includes many specific details and names, and mentions four specific incidents in which locals were involved in crimes. Some of the more damning passages from the lengthy story include:

- “The night after [the schooner James Fisher] was cast ashore, she was boarded by a gang of about 100 land pirates, and the whole of her cargo, consisting of crockery, calicoes, muslins, silks and cloths to the value of $8,000 was taken away in small boats, and secreted by the pirates in their own dwellings upon the beach, and upon the main land across the bay; leaving the ship, where she now is, high and dry on the shore. She was not insured, and the loss fell upon different merchants of Philadelphia.”

- “The night after the wreck, a gang of about 100 of these pirates (partly disguised with blackened faces), boarded the Henry Franklin while the captain was still on shore, ordered the mate to leave her, threatened the guard with death if they interfered, drove them off, forced open the hatches, and carried off 11 bags of coffee, 35 barrels of mackerel.”

- An armed confrontation between captain and mate and guard who “armed themselves…went down and put a stop to the plunder, or the entire cargo would have been stolen.”

According to the story, the insurers assigned an agent with just the name “Huntington,” who was given “authority to proceed as he thought proper, and to spare no expense in arresting the offenders,” which he apparently did with great dispatch. Some twenty boats anchored in Barnegat waters at time of the arrests all immediately set sail “and left the city that night, and have not been heard of since.”

Two thirds at least of the inhabitants…are implicated in this scandalous business, in which it appears they were led by a magistrate. They have carried on the work of piracy there for years past, and many have grown rich by the proceeds of their plunder. Heads of families, farmers, store keepers, and others, for fear of punishment, have absconded and left their families and property behind them.

We understand that the pirates used to hoist decoy lights to ensnare vessels, and it is believed that numbers of vessels have been wrecked, their cargoes stolen, and their crews murdered.

In 1834, New Yorkers had many options for getting the news, with some newspapers publishing morning editions and others publishing in the evenings. The New-York Gazette and Advertiser was a morning paper. After they ran their story, it was picked up by The New York Evening Post and published again on the same day. Over the next several weeks, about 24 newspapers around the country ran various versions of this story, some with the headline, “Banditti Discovered.”

We believe this newspaper story to be a hoax for the following reasons:

- All four shipwrecks were covered in various newspapers at the time they happened, and not one account suggested there was anything amiss. Not one newspaper in New Jersey ever published a single word about the Barnegat wreckers or of these four shipwrecks. Lurid tales of arrests, searches-and-seizures, criminal trials, jail sentences, prominent citizens sent into hiding, and other sensationalist accusations contained in this article…none of this was deemed newsworthy by the newspapers of Freehold, Long Branch, Red Bank, or Asbury Park.

- In an era when most newspaper content consisted of stories reprinted from other newspapers, few major newspapers ran this story. This is consistent with other incidents of fraudulent news stories wherein most legitimate publishers smelled something amiss and steered clear of a story thought to be bogus. A well-known example of this happened in 1864 when Joseph Howard Jr., publisher of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, sent prominent New York newspapers a forged Associated Press story in which President Abraham Lincoln apologized for his weaknesses, thereby triggering a stock market panic. Most legitimate publications sensed something fishy with the report and did not use it, but enough others did such that it gained wide circulation. We believe that to be the case here as well, that most publishers viewed the land pirates story as fiction.

- Hoaxes of this type during this period were not unusual. The New York Sun’s “Great Moon Hoax” of 1835 claimed there was an alien civilization on the moon, and established the Sun as a leading, profitable newspaper. In 1844, anti-Catholic newspapers in Philadelphia falsely claimed Irishmen were stealing bibles from public schools, leading to violent riots and attacks on Catholic churches. Both were obvious hoaxes and most legitimate publishers steered clear, or actively tried to debunk them.

- No newspaper in Philadelphia carried this story, despite Philadelphia being a major center for maritime trade and a leading source of shipping news. Philadelphia newspapers published many more stories on wreckers over the decades, compared with New York papers, yet none thought this story worth running. Philly papers were also notorious for opinion pieces comparing politicians to wreckers, yet chose not to run this.

This story includes many specifics, but almost none stand up to scrutiny. For example:

- Certain individuals are named, for example, Halcomb Everingham, Henry Schenck, and Reuben Grant. A search of newspaper archives 20 years before and after this article appeared reveals not one single mention of anyone by these names anywhere, anytime. If any of these people had gone to trial and been convicted and imprisoned, it’s almost certain some coverage would have appeared at some time.

- A reference is made to “Judge Betts” who ordered Barnegat miscreants to be held in a Newark jail to face trial there. Samuel Betts was a storied New York state jurist who was, at the time of the land pirates article, judge of the Circuit Court for the Southern District of New York. New Jersey had its own Circuit Court as of 1789, so it is highly unlikely a New York State judge would preside over criminal prosecutions and proceedings in New Jersey.

- A prominent character in this story is William Platt, Esquire, said to be a justice of the peace and the man who organized the plundering. Platt fled to escape prosecution, but was arrested in Indiana and returned to face trial. Based on a search of newspapers in New Jersey and Indiana, there was indeed a William Platt in the Monmouth County area in 1834, but he made the news for a very different reason – he failed to show up for his wife’s divorce proceedings. He was thought to be in Indiana, and according to press reports, the presiding judge stated if Platt did not return to appear in court, the case would be adjudicated without him. There is no mention of an arrest, nor of any trial. Monmouth County historian Edwin Salter refers to “the once notorious Esquire William Platt” in his Barnegat chapter (p. 240), but this reference is with respect to lawsuits filed against residents for failure to adhere to laws during the Revolution. So this reference predates the land pirates story by some 5o years.

- As sensational as this story is, it had a relatively short lifespan. The last of the approximately 24 reprints in other papers around the country ended in July of 1835. That’s important because during this period, newspapers had become the foremost source of entertainment for most Americans. The “penny press” was a mix of news and fiction, fact and myth, and it could be difficult to discern one from the other in many cases. When an unusual story such as this appeared, featuring a celebrity judge and prominent citizens named in heinous allegations, the lack of broader coverage over a longer period of time suggests that few in the newspaper business thought this to be legitimate content.

If this was a hoax, two questions arise: Who did it, and why?

A newspaper publisher, to sell newspapers? There are numerous examples of sensationalist newspaper stories, entirely fictional, published just to sell newspapers (advertising revenue was many years yet to come, newspaper revenue in this era came from sales of individual copies). The “moon hoax” previously referenced is an excellent example.

Insurance fraud? The George Canning was not insured and so its loss was born by Philadelphia merchants. Had these merchants sought to create a context for pursuing a claim, this story would have appeared in a Philadelphia newspaper. The story about the General Putnam makes reference to underwriters, so it was likely insured at least in part. And in subsequent news reports after the initial land pirates story, the Putnam’s cargo value became rapidly inflated. The insurance status of the James Fisher and the Henry Franklin is not known.

Someone with an axe to grind? The residents of Barnegat come in for a thorough tar-and-feathering in this story. Did someone have a bad experience living or doing business there who wanted to see them hurt? What kind of vendetta would lead someone to create this kind of fictitious defamation?

To improve America’s image? In the years following the War of 1812, the new nation was regarded in many corners of the world as a backwater outpost of ruffians and outlaws. Certain civic leaders, including newspaper publishers, touted the triumphs of law enforcement to promote a more positive image.

We consider this an open question that we will continue to examine.

And so the story quickly faded away with no further mentions, until national outrage over another horrible deadly shipwreck ten years later brought the old aspersions back to life, and gave them a permanence that would prove to be unshakeable.

John S. Forman: Monmouth County Wreck-Master

There may be no more persuasive repudiation of the accusations of shipwreck plundering leveled by New York newspapers against the people of Monmouth County than the official records of John S. Forman, who over the years was a justice of the peace, a county inspector, a judge, and a farmer, but more importantly, he served as the wreck-master for Monmouth County for many years. His official appointment was “Commissioner of Wrecks.”

Forman, whose father blew a fife at the Battle of Monmouth according to Edwin Salter, kept meticulous records of his marine salvage efforts, which survive today in the archives of the Monmouth County Historical Association (MCHA). These files include account books recording the names of people who came down to the shore to assist with Forman’s salvage efforts, and noting the payments due them. Numerous receipts from various people who were paid by Forman to do one or another task associated with salvaging wrecks are contained in the files. Correspondence with insurance agents that demonstrates that the business of marine salvage was a collaborative process in which the ship’s owners and agents were very much in control of the salvage, and Forman sought their direction as to how to proceed.

In some cases, insurance agents wanted their own people to salvage the wreck, and they were allowed to do so. In still other cases, agents wanted to have a representative on hand to observe the work of Forman and his workers, and this was also allowed. In other cases, ship owners could do nothing but thank Forman for having done all he could to minimize their losses. In such instances, they typically gave Forman permission to sell off all salvaged goods at auction.

Lengthy accounts detail cargo and items removed from shipwrecks. One of these lists all of the cargo salvaged from the General Putnam, which according to the New York papers, had been plundered by Barnegat outlaws. John Forman’s detailed accounting tells a very different story of what really happened.

If the New York newspapers were right, and the people of Barnegat and Monmouth County were a group of rapacious thieves, one would expect that as wreck-master, John S. Forman would be a target of enmity or vilification. In fact, some news stories that came out after the John Minturn disaster (detailed in Part Two) seemed to go out of their way to exculpate Forman, saying that the problems of Barnegat stemmed from a weak wreck-master who had been put in place after Forman – considered honest and stalwart – had been pushed out of his office due to his political inclinations. But in fact, Forman was wreck-master for many years before, during, and well after the calumny from the New York press.

Official records also include a number of letters and petitions from insurance company executives, addressed to the presiding judge, strongly encouraging the re-appointment of John S. Forman as wreck-master. This is powerful testimony that, in direct contrast to the bogus press reports, the business of wrecking in Monmouth County was conducted in an honest, transparent, and meticulously recorded manner, such that insurance agents from Boston, New York and Philadelphia all came to extol Forman’s virtues on more than one occasion.

For example, on April 18, 1837, James Bergen, a New York-based maritime insurance broker, wrote the following to J.J. Bowne, Judge of the First Circuit of New Jersey:

As an Insurance broker and agent for more than fifty Incorporated Insurance companies…it is highly interesting to me and the underwriters I represent that an honest, fearless, skillful, active man should hold the important trust of preserving life and property. John S. Forman has been long and severely tried and never found wanting in any of the above described qualifications…in the case of the Laden Packet ship Sovereign upwards of $120,000 dollars in gold was saved under his direction & $210,000 dollars in merchandise safely delivered.

Years later, Bergen again wrote to Bowne to once more encourage the re-appointment of Forman, saying, “I never knew him even by accident to employ a man who turned out dishonest,” and “I am convinced that no appointment upon our whole Coast has done more good.”

John S. Forman wore many different hats, but he was primarily a farmer. The original Forman Farm was started after the Revolutionary War by Samuel Forman, who was also a designated wreck-master. His son John took over the farm in the early 1800s. John S. Forman began taking boarders in the 1820s and gradually built a solid reputation for his homestead as a first-rate destination for city dwellers escaping the summer heat. Before his death, Forman handed over the operation to his son Sidney, who in turn sold the 250-acre farm and homestead to the Point Pleasant Land Company in 1877. The Forman Homestead was located on what is today the northwest corner of Forman and Richmond Avenues in Point Pleasant Beach in what is now Ocean County, and among its many attractions was the first bowling alley in town. An annex, which still exists, was located to the rear, at 607 Forman Avenue.

The people of Monmouth County apparently emerged from this newspaper hoax without suffering much damage other than to pride. In just eight years’ time, however, those old accusations would be leveled anew, following one of the most tragic shipwreck disasters in our regional history. Click here for Part Two of Wreckers! The Land Pirates of Monmouth County.

Sources:

An Act Concerning Wrecks. (1821). Laws of the State of New Jersey, Printed by Joseph Justice, 1821, P. 716-723.

A Banditti Discovered. (1835). The Pittsburgh Gazette, Pittsburgh, Penn., January 3, 1835, P. 2.

A Noble-Hearted Wrecker. (1849). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., October 11, 1849, P. 2.

Admiralty Law. (2021). Justia. Available: https://www.justia.com/admiralty/

Amusements. (1856). The New York Times, New York, N.Y., October 15, 1856, P. 6.

Arrest of Squire Platt, the Barnegat (N.J.) Moon Raker. (1837). Boston Post, Boston, Mass., February 16, 1837 P. 2.

Arrived This Forenoon. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., January 12, 1832, P. 2.

Averill, Charles E. (1848). The wreckers, or, The ship-plunderers of Barnegat, a startling story of the mysteries of the sea-shore. F. Gleason, Boston, Mass.

The Banditti Discovered. (1835). Originally published by the New York Courier, reprinted in the Vermont Phoenix, Brattleboro, Vt., January 9, 1837, P. 2.

Capture of Land Pirates. (1834). The New-York Gazette and Advertiser, New York, N.Y., December 29, 1834, P. 1.

Capture of Land Pirates. (1834). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., December 29, 1834.

Capture of Land Pirates. (1834). The National Gazette, Philadelphia, Penn., December 31, 1834, P. 2.

Capture of Land Pirates. (1834). Sag Harbor Corrector, Sag Harbor, N.Y., December 31, 1834, P. 5. “From the N.Y. Gazette.”

Charles-Town, August 9. (1768). The South Carolina Gazette, Charleston, S.C., August 9, 1768, P. 4.

The Chronometer Found. (1846). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, N.Y., April 24, 1846, P. 2.

Coast Piracies – The Barnegat Pirates. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 26, 1846, P. 2.

Coddington, Ronald S. (2021). Fake News, 1864. The Civil War Monitor, Longport, N.J., Spring 2011, P. 12.

Dreadful Shipwrecks – Disastrous Results of the Storm. (1846). The Somerset Herald, Somerset, Penn., March 3, 1846, P. 2.

Extract of a letter from Antigua, dated April 26. (1789). Poughkeepsie Journal, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., June 16, 1789, P. 3.

Extract of a Letter from Brigthelmstone, Jan. 14. (1746). The Caledonian Mercury, Edinburgh, Scotland, January 24, 1746, P. 3.

Fowles, John. (1975). Shipwreck. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, Mass.

Historical currency converter. (2021). Available: Historicalstatistics.org.

Humanity in New Jersey. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 23, 1846, P. 2.

In Chancery of New Jersey. (1838). Monmouth Inquirer, Freehold, N.J., December 6, 1838.

Interesting Details of the Late Storm – Inhospitality – Barnegat Pirates. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 19, 1846, P. 1.

Graham, David A. (2021). Why Ships Keep Crashing. The Atlantic, March 27, 2021. Available: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/03/ever-given-and-suez-why-ships-keep-crashing/618436/.

The Jersey Pirates. (1846). Public Ledger, Philadelphia, Penn., March 2, 1846, P. 2.

Jerseymen on the Coast. (1854). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., May 25, 1854.

Special Report by the Commissioners to Investigate the Charges Concerning the Wrecks on the Monmouth Coast. (1846). Journal of the Proceedings of the Second Senate of New Jersey, Convened at Trenton, January 30, 1846, P. 588-603. Available: https://www.njstatelib.org/research_library/legal_resources/historical_laws/legislative_journals_and_minutes/.

Lawrence, Iain. (1998). The Wreckers: The High Seas Trilogy, Book 1. Yearling, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, N.Y.

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping. (1890). Lloyd’s Register Wreck Returns, 1st July to 30th September, 1890. November 27, 1890. Available: https://hec.lrfoundation.org.uk/archive-library/casualty-returns

Local News, Gossip, &tc. (1854). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., June 1, 1854, P. 2.

Loss of the ship George Canning. (1832). Washington Globe, Washington, D.C., January 13, 1832, P. 3.

Maloney, E. Burke. (1967). They Lured Vessels Ashore. The Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., July 30, 1967, P. 15.

Marine List. (1834). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., September 9, 1834, P. 3.

Means, Dennis R. (1987). A Heavy Sea Running: The Formation of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1846-1878. Prologue Magazine, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Winter 1987, Vol. 19, No. 4. Available: https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1987/winter/us-life-saving-service-1.html#SL4.

Melancholy Shipwrecks. (1846). Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, London, England, March 22, 1846, P. 7.

Memoranda. (1834). The United States Gazette, Philadelphia, Penn., October 18, 1834, P. 4.

Mills, Franklin S. (1856). Of the session of 1856. Legislative Journal of the seventy-second Legislature of the State of New Jersey, containing the debates, proceedings and list of acts of the session, commencing January 8, 1856, P. 64.

Miscellany. (1855). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., January 18, 1855, P. 1.

Nagiewicz, Stephen D. (2016). Hidden History of Maritime New Jersey. The History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2016

The New York Pilots – False Statements Against Them – Their Case. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., March 5, 1846, P. 2.

Newport, June 17. (1765). The Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia Penn., June 27, 1765, P. 2.

Noble, Dennis L. (1994). That Others Might Live: The U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1878-1915. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md, 1994.

Occurrences of the Day, &c. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., February 20, 1832, P. 2.

The Outrages at Squan Beach. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 28, 1846, P. 2.

The Poet’s Corner. (1838). Monmouth Inquirer, Freehold, N.J., February 22, 1838, P. 1.

Port of Philadelphia. (1834). The National Gazette, Philadelphia, Penn., December 2, 1834, P. 2.

Public Acts of the Thirtieth Congress of the United States. (1848). August 14, 1848, P. 114. Available: https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/30th-congress/c30.pdf

Resolutions have been introduced. (1846). Brooklyn Eagle, Brooklyn, N.Y., February 28, 1846, P. 2.

Salter, Edwin. (1890, 1997, 2001). Salter’s History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties New Jersey. A facsimile reprint, published 2007. Heritage Books, Inc., Westminster, Md. Available: https://books.google.com/books?id=XqchvDnzm0wC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Shepard, Birse. (1961). Lore of the Wreckers. Beacon Press, Boston, Mass., 1961.

Ship George Canning. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., January 13, 1832, P. 2.

Ship News. (1834). The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, S.C., October 30, 1834, P. 2.

Shipwrecks. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., February 3, 1832, P. 2.

Soll, Jacob. (2016). The Long and Brutal History of Fake News. Politico Magazine, December 18, 2016. Available: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/12/fake-news-history-long-violent-214535/

Stranding of the Ship General Putnam. (1832). The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, S.C., February 11, 1832, P. 3.

The Terrible Storm, On Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 17, 1846, P. 2.

Timeline 1700’s-1800’s (sic). (2020). United States Coast Guard Historian’s Office. Available: https://www.history.uscg.mil/Complete-Time-Line/Time-Line-1700-1800/.

Uberti, David. (2016). The Real History of Fake News. Columbia Journalism Review, December 15, 2016. Available: https://www.cjr.org/special_report/fake_news_history.php

U.S. District Courts for the Districts of New Jersey: Legislative History. Federal Judicial Center. Available: https://www.fjc.gov/history/courts/u.s.-district-courts-districts-new-jersey-legislative-history.

Whitman, Walt. (1855). Leaves of Grass. Reprinted by The Modern Library, New York, N.Y., 1921.

Woolley, Jerry A. (1995). Point Pleasant. Arcadia Publishing, Dover, N.H., 1995, P. 17.

The Wreckers. (1877). The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, Penn., April 24, 1877, P. 4.

The Wreckers of New Jersey. (1846). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., March 2, 1846, P. 2.

The Wrecks on the Jersey Shore. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., March 3, 1832, P. 2.

Distressing Shipwreck. (1816). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., Jan. 11, 1816, Page 2.

Leave a Reply