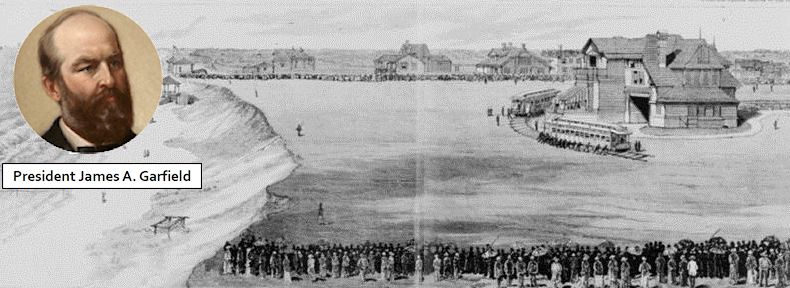

On September 19, 1881, U.S. President James A. Garfield died in Long Branch, exactly two months before his 50th birthday. He had asked to be brought to Long Branch in the hope that the fresh air and quiet might aid his recovery after being shot on July 2, 1881, an incident that left an assassin’s bullet lodged in his back.

Garfield was a compromise candidate for the Republican party, which continued to hold power in the years following Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. Factions within the Republican Party became so intensely opposed on issues such as patronage jobs that it led to Garfield’s murder. Assassin Charles J. Guiteau, an unemployed 39-year-old drifter with a history of mental illness, believed that killing Garfield, and ushering Vice President Chester A. Arthur into the presidency, would result in more fair allotment of highly sought-after government jobs.

Despite Abraham Lincoln’s assassination still being fresh in people’s minds, Garfield, like his predecessors, traveled without bodyguards or protection, and Washington, D.C. newspapers published his travel plans, so he was a very easy target. Guiteau had several chances to encounter Garfield in person, up close, and on July 2, walked up to the president at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, and shot him twice, hitting him once, in the back. He was hanged for his crime about a year later.

The real tragedy of Garfield’s death was that the bullet in his body missed major organs and might well have proved not to be fatal, had the medical practices of that era been more advanced. Doctors of that time did not understand the potentially fatal role of bacteria that could be transferred to a patient from unclean hands and unsterilized surgical tools. Garfield’s condition steadily declined as he lay in the sweltering summer heat and humidity of the District of Columbia in mid-summer, where residents also faced a malaria outbreak. Garfield’s first choice would have been to be transferred to his farm in Ohio for a better chance of recovery, but that trip was a long and daunting journey in those days, and so Garfield, his wife, and his doctors all agreed that the cool ocean breezes of Long Branch, about 7 hours away by train, would be the best place to go.

Charles G. Francklyn, an executive with the British-owned Cunard Line shipping conglomerate, offered the first family his oceanfront mansion, Francklyn Cottage, adjacent to the Elberon Hotel. Francklyn Cottage burned down on June 14, 1920.

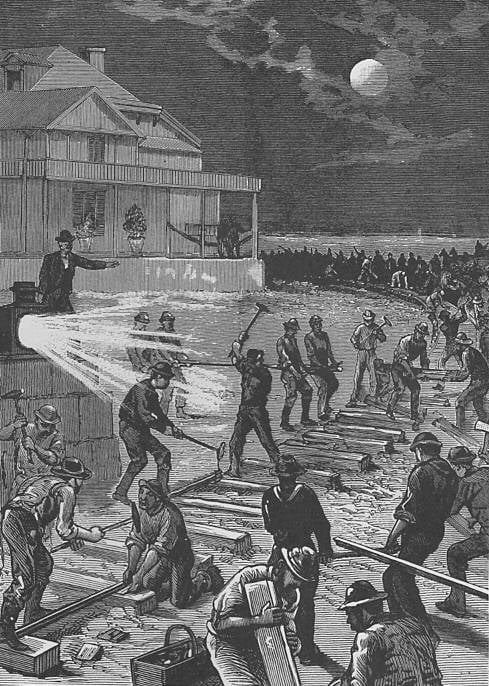

Traveling by train from Washington, D.C., to Long Branch was commonplace in those days. The challenge was how to get the ailing president from the train station to the oceanfront mansion. Roads in those days were unpaved and very rough, and so the only viable solution was to build a new rail spur running about a half mile, right down what is now South Lincoln Ave.

The problem was that by the time this solution appeared as the only viable one, there was little time left. The president’s train, a locomotive pulling three cars, would be on its way in a matter of hours. The rail workers and volunteer army worked all through the night, using torches for light, and completed the new spur with time to spare.

The crowd stood and cheered as the presidential train made its way slowly eastward toward the beach. Once it reached the house, it turned out that the curve of the track was too sharp for the locomotive (see image above). Ultimately, the crowd ended up pushing the president’s train cars around the bend to the front of the house to complete the trip, taking pains to make no sound so as to not disturb the president.

For the next 13 days, Long Branch was the seat of federal power after most of Garfield’s cabinet and the White House press corps took up residence throughout the area, mostly in the Elberon Hotel and the Elberon Casino.

After his death, the president’s funeral train departed Long Branch the same way Garfield arrived. Shortly thereafter, the railroad spur, built overnight on the president’s behalf, was dismantled. A stone marker now sits on Garfield Road near where the Francklyn Cottage was located, commemorating the place of death of America’s 20th president. Garfield is included within several Monmouth County claims regarding the fabled “seven presidents.”

Source:

Larsen, Erik. (2017). A Sitting American President Dies In Long Branch. Asbury Park Press, September 19, 2017. Available: https://www.app.com/story/news/history/erik-larsen/2017/09/19/sitting-american-president-dies-long-branch/667661001/.

Images:

The removal of President Garfield, with his physicians and attendants, from the White House to the Francklyn Cottage, at Elberon by the sea, September 6th. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, September 24, 1881, Library of Congress. Public domain.

Rail Spur for a President. Workmen and volunteers are shown laying track at Elberon on the night of Sept. 5, 1861, in anticipation of the arrival the next day of President James A. Garfield, who had been struck down by an assassin’s bullet July 2 and was near death. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, September 24, 1881, Library of Congress. Public domain.

There was a tool shed on the property of Oliver Pressley on Atlantic Avenue in North Long Branch. It was, according to an unsubstantiated story I heard, made from some of the railroad ties from that spur. I lived on Atlantic Ave until aged 10 in 1957 and used to visit Mr. Pressley and “help” him mow his lawn. The mower was stored in that shed. I don’t know if that shed still exists and if it was actually made from the ties from that spur. My memory is that it was made from wood consistent with ties but that is the extent of my certainty.