Editor’s note: This article would not have happened were it not for the diligence and professionalism of a dedicated librarian, Caitlyn Cook, at the New Jersey State Library in Trenton. Ms. Cook was helping with my research on the wreckers of the Jersey Shore when she came across a collection of original source documents. The Annual Reports of the New Jersey Commissioners of Pilotage relate the courage, skill, and sacrifice of the Sandy Hook Pilots and provide a gripping and detailed story of the pilots who operated under daunting and often deadly conditions, ensuring that ships made it safely in or out of port. Monmouth Timeline is grateful in the extreme to Ms. Cook and the New Jersey State Library for not only making this story possible, but so much richer and fuller.

By John R. Barrows

On August 22, 1851, a yacht race was held in England that made history. The captain who won that race was considered the very best of the best seamen of his time. And he was a New Jersey Sandy Hook Ship’s Pilot by trade.

Richard Brown, known as Dick, was born July 3, 1810, in Mystic, Connecticut, the son of a ship’s carpenter. He started out his working life as a fisherman when he and four other boys ran away from home and went to sea. All five became captains, although the other four eventually drowned. Among them had been Captain and Master Dudley Stark, who with his wife and dozens of others, perished in the tragic wreck of the John Minturn off the coast of Monmouth County in 1846, despite the efforts of the New York Sandy Hook Pilot on board, who also died in the blizzard. (A monument to that heroic pilot was erected in Brooklyn’s Greenlawn Cemetery.) Dick Brown, however, followed a more fortuitous path and is revered as one of the most accomplished captains and seamen in U.S. history.

While his young friends sailed the seven seas, Dick Brown signed on with the United States Coast Survey and worked as a buoy-setter along the Jersey coast from New York to Delaware, which gave him a detailed knowledge of local channels and marine hazards. In 1841 he was licensed as a pilot and joined the New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots, where he gained the reputation for being “one of the most skillful sailing masters in these waters.”

In 1851, a group of wealthy New Yorkers arranged for the design and construction of a yacht intended to be as fast and sturdy as possible. Named America, it was entered into the 1851 Royal Squadron regatta in England, a yacht race around the Isle of Wight that became an annual event.

George Steers, the designer of America, had suggested to the New York Yacht Club that Captain Brown, “an excellent and suitable man,” be engaged as skipper. George L. Schuyler, one of the club members, claimed that Brown was “careful, reliable, faithful, one of the best men in his position I ever saw.” Captain Brown directed the logistics of the sailing campaign and undertook the training of the crew.

America, the sole entry from the U.S., was racing against a fleet of 14 or 15 of the fastest British yachts — accounts vary as to the exact number — starting at 10:00 in the morning of August 22. By late afternoon, Queen Victoria, observing the race at some distance aboard the royal yacht Victoria and Albert, supposedly asked aloud:

“Are the yachts in sight?”

“Only the America. May it please your Majesty,” replied the signal-master, according to an account published by American Heritage Magazine in August 1958.

“Which is second?” the queen queried.

“Ah, your Majesty, there is no second.” That answer has resounded in history but is largely believed to be legend. There is no verification that the queen and signal-master ever had this conversation, but it has become part of America’s lore.

At the end of the race, America had bested the swiftest sailboats of the day. Captain Brown’s command made the difference that won the trophy.

The yacht returned to the U.S. a heralded champion. Subsequent races to challenge this supremacy became known as the America’s Cup.

After winning the Royal Squadron race, and returning home as a conquering hero, Brown resumed his service with the New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots. He continued to be recruited to skipper yachts in high-stakes events, including subsequent America’s Cup races. At the time of his death, he was the most senior pilot in the history of the New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots service.

The 1885 Annual Report of the New Jersey Commissioners of Pilotage sadly noted Brown’s passing, and added that his death had resulted from “his feet having been frozen while he was on the bridge of a steamer, in the performance of his duty. As long as he was able, he clung to his post.” His brother later said, “It was the coldest night of the winter, and as there wasn’t steam enough to bring the vessel into port my brother caused her to be anchored. For twelve hours – in fact, all night – he remained on the bridge unprotected, and at sometimes his feet were so cold that they brought hot ashes from the fire-room, which they placed about them.” But the damage was so severe Captain Brown never went to sea again. Brown died in his home in Brooklyn on June 18 as a result of injury suffered in the line of duty.

Brown exemplified what it meant to be a New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilot, with peerless seamanship and navigation skills, and an encyclopedic knowledge of the channels and hazards of the entrances to New York Bay and Harbor. He was dedicated and fearless, and these characteristics undoubtedly had contributed to his death. To this day, Captain Dick Brown remains the epitome of the courage, skill, and sacrifice that are still the hallmarks of the Sandy Hook Pilots, as expressed by their motto: “Always on Station.”

Clarifications are in Order

Several terms used throughout this story have meanings specific to the world of ship’s pilots that can be confusing if not clarified at the outset.

Pilots

To most people today, the word pilot means an aviator. But while aviation has been in existence for little over a century, ship’s pilots have been known by that name for as long as ships have engaged in maritime commerce, that is, for millennia. In this story, all references to a pilot indicate a ship’s pilot, and not an aviator.

Captains

For as far back as written records exist, there have been two types of ship captains. The type of captain many people are familiar with is the ship’s leader who takes a vessel across a large body of water or along a major waterway. That “captain” is called the ship’s master. The other person who, by longstanding tradition, is also addressed as “captain” is a specialist who is a trained and certified expert on local waterways and channels, marine hazards and underwater obstructions, anchorage procedures, and local laws, and who guides a vessel into or out of major ports of call. That “captain” is called the ship’s pilot. Commercial ship traffic and navigational complexities vary greatly from one port to another, and no ship’s master is expected to be able to complete a voyage without the services of a pilot. For that reason, for vessels of certain size and circumstance, the use of a pilot today is compulsory at major ports around the world.

Throughout this story, all captains who are ship’s masters will be identified as masters, and all other references to a captain will refer to ship’s pilots.

Sandy Hook

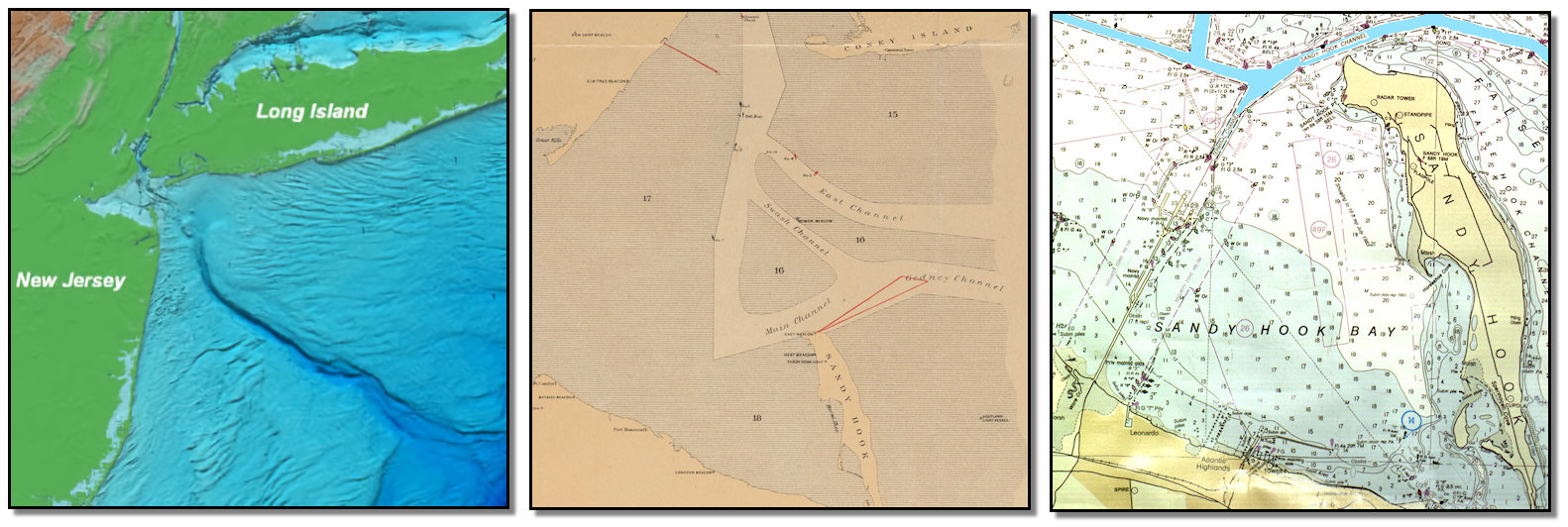

As the American colonies grew as a source of international trade during the 18th century, more and larger ships sought access to New York Harbor. But for the larger ships, this access was only possible by sailing through natural deep-water channels created by the receding glaciers that had carved out the Hudson River. These channels run very close to the far tip of Sandy Hook and are subject to constantly shifting sandbars and currents, with rocky outcrops and barely visible small islands scattered throughout the area. Entering New York Harbor meant having to “cross the bar,” or “passing the bar,” that is, getting safely past Sandy Hook via the deep-water channel. Often, a sudden change in wind and weather meant a ship safely in the channel, but still on the windward side of Sandy Hook, could easily be blown out of control and wrecked on the coastlines of this region, something that happened far too often in those years.

The primary purpose of the New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots was (and is) to prevent such shipwrecks. This made them the first line of organized defense, along with lighthouses, buoys, and channel markers, and the U.S. Life-Saving Service and its volunteer predecessors, known as “wreckers,” who effected rescues and marine salvage from shore, as regulated by state law.

Despite what the name suggests, the Sandy Hook Pilots have never been based at Sandy Hook, and the pilots themselves are not necessarily from, nor do they live in, New Jersey. For most of their history, the New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots have been based on Staten Island, where they are headquartered to this day. Since the mission of the pilot boats is to meet client vessels well out at sea to ensure a smooth entry, where the pilot boats disembark from is irrelevant.

It takes the best of the best navigators to be able to take any kind of ship across the bar, and that bar is Sandy Hook, and that’s why they are the Sandy Hook Pilots.

Yawls

Today’s modern pilot boats are made to be able to get right up against a ship so that the pilot can board via a ladder (more on this later), and if the pilot slips, he or she falls back into the pilot boat rather than the sea. But for centuries, pilot boats were sailboats that approached commercial vessels and, upon being retained for pilot services at a safe distance, would launch a sturdy rowboat, typically oared by two pilot apprentices, to convey the pilot to his assignment. The pilots called those rowboats “yawls,” which was a common term for small boats carried by larger boats. Over time, especially with the advent of recreational sailboats in the 20th century, the term yawl became more familiar to many as a type of sailboat, one with two masts, a mainmast and a mizzenmast aft of the rudder. Within this story, all references to a yawl will refer to a pilot boat rowboat.

Ship’s Pilots: As Old as Maritime Commerce

Ship’s pilots have been in existence for at least as long as navigators have attempted travel beyond safe and known waters. Homer mentions a pilot in the first book of The Iliad. Roman law made the use of a local navigation expert compulsory, else a ship’s master could be held responsible for damage or loss from a wreck or grounding. Chapter 27 of Ezekiel in the King James Bible refers to ship’s pilots four times. Amerigo Vespucci, the early Italian explorer, was appointed Chief Pilot, or Pilot Major, of Spain in 1508, and another early explorer, Sebastian Cabot, was appointed Grand Pilot of England. It is no coincidence that these early legends of transoceanic exploration were considered the best pilots as well.

The first known modern organized pilotage system is believed to have originated in The Netherlands. In fact, the word “pilot” comes from the Dutch words pijl and lood, referring to the sounding lead used by generations of pilots. Dutch pilots used these long poles to take depth soundings and ensure safe passage into or out of port for commercial vessels. Henry Hudson, exploring our region for the Dutch in 1604, employed pijl loods to take soundings for three days before moving up the river that now bears his name.

Frans Naerebout, a Dutchman born in 1749 who devoted most of his life to pilotage, is generally credited with developing modern pilotage into a science. A monument to his memory stands at Flushing, Netherlands.

The evolution of pilotage in America can be seen in three distinct eras:

| 1604-1836 | This era could be called the Free-for-All stage. Henry Hudson recorded the soundings taken in and around the approaches to what would later be known as New York Harbor. Dutch colonists settled the area and brought with them their organized approach to pilotage. Throughout this period, few pilots were formally certified, there were few standards and little oversight, and each person who wanted to offer his services as a pilot could compete with the others for incoming or outbound vessels, essentially acting as independent contractors. This resulted in something of a free-for-all with ships unfurling every possible stitch of sail to race as a group toward a potential client. It was not considered an effective approach, and there were many calls for reform. |

| 1837-1894 | This period could be described as the Pilot War between New York and New Jersey. New Jersey passed state law establishing its own organized and systematic approach to pilotage, the farthest-reaching act of legislation passed by any state at this time. This created the New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots as a distinct and separate entity from the New York Sandy Hook Pilots. Boats, pilots, and crews from the two groups engaged in vigorous competition among one another for pilotage business. This was considered a vast improvement over the previous approach, but the competition created problems, and it exposed pilots, boats, and crews to unnecessary risks. |

| 1895-present | United at Last. In 1895, the New York and New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots joined to form a single organization that has remained in operation ever since. This ended the era of competition for pilotage in favor of a systematic approach of taking turns, ensuring pilots were always fresh and rested for each new assignment, and conserving resources wasted in competition. This has proven to be immensely successful. |

The First Ship’s Pilots in the American Colonies

The earliest references to pilots in the American colonies dated from the first English and Dutch settlements, specifically New Amsterdam, Plymouth, Jamestown, and the Chesapeake Bay area.

Plymouth

The first known pilots in the Americas had been indigenous people who sometimes assisted European settlers with navigational guidance. One of the most famous native Americans of that period was Tisquantum (c. 1585 [±10 years]–1622), more commonly known as Squanto, who was a member of the Patuxet tribe. Tisquantum is best known for being an early liaison between the Native American population in southern New England and the Mayflower Pilgrims who made their settlement at the site of Tisquantum’s former summer village.

The Plymouth settlers found a region rich in fish and shellfish, but also fraught with dangerous shoals and sandbars, and they found themselves greatly reluctant to attempt to travel around Cape Cod without Tisquantum’s expert guidance. Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford relied on Tisquantum to pilot his boats to where food could be found. It was while serving as a ship’s pilot, guiding a group of settlers around the tip of Cape Cod in search of food, that Tisquantum contracted a fever from which he died a short time later. This is the first known instance in the Americas of a ship’s pilot dying from a disease contracted while in the line of duty – but he would not be the last.

The Boston Marine Society, with its oversight of pilotage in New England, was formed in 1754. In the early colonial years, for the most part, there were no licensed pilots, nor men who specialized in piloting as a trade. Instead, foreign vessels contracted on the fly with fishermen or other locals, such as Tisquantum, to help them navigate through the channels and into the safety of Boston Harbor.

New Amsterdam

The importance of pilots in the exploration and settling of the new American colony by the Dutch is captured in an early official seal of New York City in 1686. On the right, the seal shows a Native American with a bow; in the center is a shield with Dutch windmill vanes, two beavers, and flour barrels, signifying trapping and milling. On the left is a Dutch male holding a lead plummet, that is, a weighted plumb line used for measuring water depths; over his shoulder is a cross-staff used for measuring latitude.

In colonial times, pilots were independent competitors who were not known to roam around at sea looking for client vessels. Until 1837, there were only loose organizations or associations for pilots. According to one source, in 1810 there were ten Sandy Hook pilots and in 1822, just six.

The State of New York had been issuing pilot’s licenses for New York waterways as far back as 1784, but piloting remained “every man for himself” for decades. In time, tragic events would make it clear that pilotage required further oversight and organization.

On November 20, 1836, the bark Bristol, an American flagship carrying 100 passengers from England, with a crew of 16, arrived just off the Sandy Hook lightship, and signaled first with flags and then with guns their desire to have a pilot come out and take charge of the vessel. At that time, the number of pilots was limited by statute, and it was not uncommon for more than a dozen vessels to be waiting out at sea for a pilot to take them into New York Harbor.

On this occasion, many of the pilots were further out at sea seeking client vessels. In terrible weather, the remaining few available pilots remained on their boats safely inside Raritan Bay, protected by Sandy Hook. The Bristol was blown onto the shallows off Long Island about a half mile from shore, where the rough conditions prevented volunteer life-saving crews from putting boats in for rescue. Finally, a life-saving team reached the ship and was able to rescue 32 people, but 84 crew and passengers of the Bristol died from exposure or drowning.

Just weeks later, the Mexico, another ship from England carrying immigrants, arrived off Sandy Hook, signaled for a pilot, but found none who were willing to risk leaving the safety of port in a storm. Gale-force winds forced the master to run his ship aground, believing this to be the best means of survival. On January 3, a life-saving crew was able to reach her and saved eight people clinging to the bowsprit, including the master, but the remaining 158 passengers and crew all perished, with most bodies never recovered. The master of the Mexico was blamed and stripped of his license; he never captained a ship again. But soon, outrage focused on the pilots. After detailing the extent of the suffering, the New York Herald said, “Again has our atrocious pilot system, or rather our want of all system, sent over a hundred human beings to a watery grave.”

Inquiries failed to find individual pilots culpable, but did reveal that there were many more ships in need of pilot services than there were available pilots and pilot boats and that organized oversight was needed. While New York would not take action for some time, New Jersey passed landmark legislation that other states would soon follow to address similar lapses.

A Brief History of New Jersey Ship Pilot Legislation and Regulation

The U.S. Constitution assigns the oversight of interstate and foreign commerce to the federal government, but regulation of pilotage was excluded, and hence, left to the states. Among the reasons for this is the fact that many major waterways, for example, the Hudson River and the Delaware River, are also state borders, and those are considered state territorial waters, while the federal government is responsible for regulation and patrol of U.S. territorial waters, that is, the oceans, Great Lakes, and Gulf of Mexico.

1694: On March 9, the third assembly of the Colony of New York passed “An Act for Settyling [sic] Pilotage for all vessels that shall come within Sandy Hook.” The Act was passed in order to give aid and assistance to all vessels that were bound for the ports of New York and New Jersey.

1784: On April 14, the New York State Legislature passed “An Act for the regulation of pilots and pilotage for the Port of New York,” which set forth pilotage fees, pilot salaries, and rules and procedures.

1789: On August 7, the U.S. Congress clarified, “All pilots in the bays, inlets, rivers, harbors, and ports of the United States, shall continue to be regulated in conformity with the existing laws of the States respectively wherein such pilots may be, or with such laws as the States may respectively hereafter enact for the purpose, until further legislative provision shall be made by Congress.” Under this act, pilots of one state could not bring a vessel into waters of another state, which created “confusion and jealousy.”

New York State regulations set the number of licensed Sandy Hook pilots at 30, regardless of how many ships sought entry to New York or New Jersey ports. A new pilot could only be licensed if one of the existing 30 died, resigned, was fired, or became incapacitated. Many believed that the system was failing both the maritime trade and port authorities.

1837: On February 8, in response to the disasters of the Bristol and the Mexico, the New Jersey Legislature passed an act that created the New Jersey Board of Commissioners of Pilotage to deploy ship’s pilots focusing on New Jersey ports. Just weeks later, on March 2, the U.S. Congress passed a new law codifying the open competition for piloting among states sharing boundaries:

That it shall and may be lawful for the master or commander of any vessel coming into or going out of any port situate upon waters which are the boundary between the States, to employ any pilot duly licensed or authorized by the laws of either of the States bounded on said waters, to pilot the said vessel to or from said port, any law, usage, or custom to the contrary notwithstanding.

This engendered a “spirited competition” between New York and New Jersey pilots, and in 1848, the New York pilots’ association made efforts to have Congress repeal the Act, unsuccessfully.

The 1837 law called for New Jersey’s governor and state council to appoint at least one commissioner of pilotage each from the counties of Bergen, Essex, Middlesex, and Monmouth, seven commissioners in total, and they were to take charge of “any person to act as a branch pilot off the bar at Sandy Hook, or of the river Raritan, or the harbours of Jersey City, Newark, or Perth Amboy.” The commissioners were responsible for the licensing of pilots, and were required to make annual reports to the secretary of state accounting for the annual number of ships taken in or out of those ports by New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots.

1852: Cooley v. Board of Wardens of the Port of Philadelphia, 53 U.S. (12 How.) 299

On March 2, 1852, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on a Pennsylvania law that required that all ships entering or leaving the port of Philadelphia hire a local pilot. Cooley was a consignee of a vessel that failed to use a local pilot. The Court held that the law requiring all ships entering or leaving Philadelphia to hire a local pilot did not violate the Commerce Clause of the Constitution. Those who did not comply with the law had been required to pay a fee. Justice Benjamin R. Curtis wrote, “It is the opinion of a majority of the court that the mere grant to Congress of the power to regulate commerce, did not deprive the States of power to regulate pilots, and that although Congress had legislated on this subject, its legislation manifests an intention, with a single exception, not to regulate this subject, but to leave its regulation to the several states.”

1854: The State of New York passed an act similar to that of New Jersey in 1837 creating the New York Board of Commissioners of Pilotage, to bring under control a system that had become chaotic and unsafe because “commercial pressures and risk taking took precedence over navigational safety.”

1894: The New Jersey Commissioners of Pilotage added a committee on “Obstructions, Fisheries, Wrecks, &c., &c.”

“Obstructions” typically referred to illegal dumping in ship channels which created obstacles for shipping; “Fisheries” was acknowledgement that pilots had to contend with all manner of boats engaged in fishing in and around New York Harbor, New York Bay, Raritan Bay, and Sandy Hook, etc., and regulations were necessary to prevent fishing boats from making ship channels impassable due to traffic congestion; and “Wrecks” were a simple fact of life in any major port. Vessels of any kind, for a myriad of reasons, collided, became leaky, ran onto rocks, caught fire, etc., and sunk almost anywhere, creating impediments to safe navigation for marine commerce. This new committee was funded to direct resources to those obstructions, fishery concerns, or wrecks that represented the greatest threats to pilotage. Year after year in pilotage annual reports, the Commissioners advocated to the legislature for responsible management of fisheries and greater penalties for illegal dumping.

The Commissioners also urged regulation over potential hazards to shipping such as limits on the number of coal barges under tow at once. Better and more powerful tugboats meant more barges could be taken along on a voyage, but these longer trains were often hard to control and could force other ships to take evasive action.

I895: The New York and New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots joined into one economic organization to better serve the port and enhance the safety of pilots.

1898: Pilot licensing began for different channel depths, e.g., 18 ft., 22 ft, with less experienced pilots working the deeper, less hazardous channels. Over time, new legislation was passed in New Jersey making the use of pilots compulsory for certain types of vessels and for the collection of pilotage fees from all inbound ships whether or not they used a pilot. Laws were passed clarifying disciplinary procedures and appeal processes for when a pilot was accused of dereliction of duty.

How the Sandy Hook Ship Pilots Operated

https://www.loc.gov/item/2013604960/

Above: A Sandy Hook pilot in his standard formal business attire, departing a client vessel off Sandy Hook, filmed in 1903 by Thomas A. Edison. Photographed off Sandy Hook in late 1902. Image credit: Library of Congress.

Today, arrangements for pilots are made using modern communication technology, and pilot boats await inbound vessels and meet them by appointment 20 to 30 miles out from the entrance to New York Bay. The pilot boats, every bit as sturdy as those of the U.S. Coast Guard, are made to come alongside the commercial vessel and enable the pilot to access the ship.

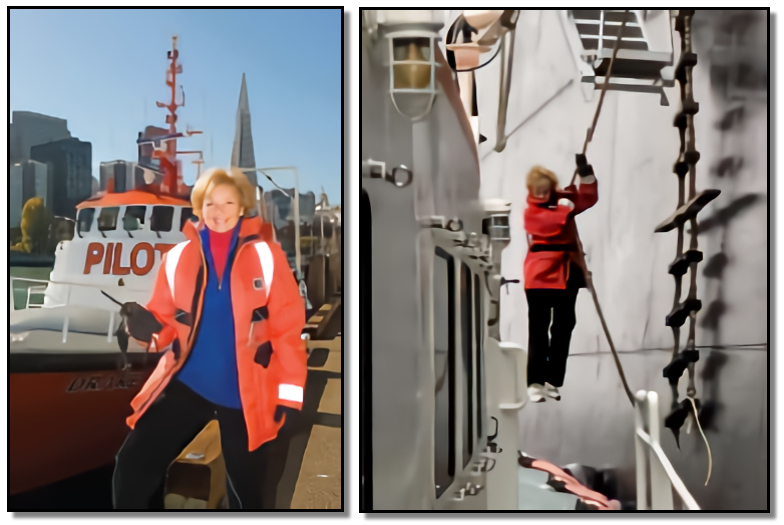

The means of pilot access to ships today varies. Some have large openings in the side of the hull that permit pilot access, but many others still require a pilot to clamber aboard, over the top rail, using a “pilot’s ladder,” typically a rope or chain ladder of a regulated width with wooden or other steps that act as spreaders. If this sounds like a dangerous way to board a ship, it most certainly is:

Pilots daily experience poor, broken, unrepaired ladders, poorly secured or cock-billed ladders, ladders that are hung by catching a rung over a cleat on a rail without a lashing, ladders with slack in them that drop when weight is put on them.

Once aboard, the pilot is given a formal welcome from the master, and command of the ship, in nautical terms called “the conn,” is transferred from the master to the pilot. Once the ship has reached its destination, either safely within port or out in open water, the pilot returns to his pilot boat or land base via another boat, and then heads back out at sea and awaits the next opportunity. While the ship’s master will typically wear a nautical uniform, ship’s pilots by longstanding tradition have worn formal business attire, including top hats when they were in fashion. As such, there has never any confusion aboard ship as to who is master, and who is pilot.

The procedures for pilotage prior to the advent of steam-powered pilot boats is described in the New Jersey Commissioners of Pilotage Annual Report for 1898:

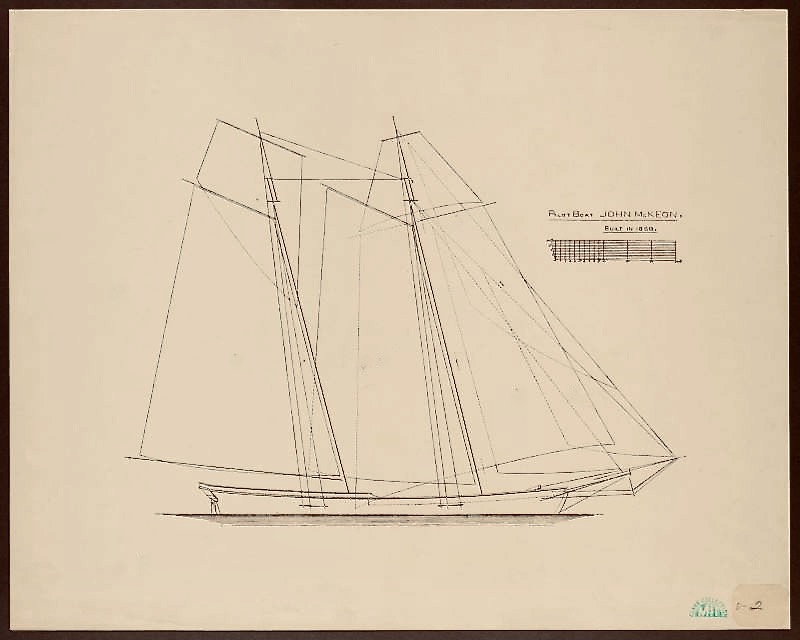

In the natural order of things, the surest way to have intercepted a ship would have been for the pilot boat to cruise a few miles outside of Sandy Hook, where all incoming vessels must pass; but the rivalry between the boats frequently caused them to push out as far as five or six hundred miles to the east. When a steamer was sighted there would be a hard race to meet her, every stitch of canvas that the spars would carry being spread; under the old system, speed was of the highest importance, and the boats were modeled and rigged with all the care and expense of modern racing craft, carrying heavy canvas so rigged as to be capable of being quickly made snug to meet a sudden blow and high sea. These long cruises, extending from New York to the capes of the Delaware on the south, and to the east from New York to Halifax, were full of disaster, costly, and unnecessary.

These pilot boats had to be sturdy enough to sail in all weather, at all times of year. While many types of sailing ships were used as pilot boats, it soon became clear that the Dutch schooner rig offered the greatest combination of speed and the ability to successfully retain navigational control in severe storm conditions.

Yawls were rowed by apprentice pilots while the pilot boat operator, or boatkeeper, always remained on board the pilot boat. Once the pilot was safely aboard the client ship, the pilot boat returned either to base, if no more pilots were aboard, or if more pilots were still aboard, the boat resumed patrolling a certain region out at sea, called a station. Pilots in the Age of Steam, generally considered to have begun around 1800, were typically aboard client vessels for about eight hours. In the Age of Sail, pilots were aboard much longer. It was not unheard of for changes in weather to make it impossible for a pilot to be able to return to his pilot boat or land base, and in those instances the pilot had no choice but to remain on board until the client vessel reached its destination, whereupon the pilot would find transportation back to America. There is one instance where a major storm resulted in nine New York or New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots all being forced to make involuntary transatlantic voyages on the same day, causing a lengthy disruption to normal pilotage.

Pilot boats were often deployed at sea for twelve months of the year, 24 hours per day, regardless of weather, returning only to take on fresh pilots, and taken offline only for maintenance and upkeep.

Commercial vessels carrying cargo or freight were the primary clients for pilots, but pilots also took charge of passenger ships, including luxury cruise liners, as well as military vessels, and even high-end super-yachts used for leisure travel. While for certain ships having a pilot aboard is compulsory, today any vessel can request, and receive, the services of a pilot.

The Sylph, New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilot Boat No. 1, 1834 – 1851

The Sylph was built by wealthy Boston merchants as a racing yacht and is believed to have taken part in the first recorded yacht race in America, off Falmouth Heights on Cape Cod.

The Sylph sailed out of what is today Vineyard Haven, on Martha’s Vineyard, skippered by a Boston ship’s pilot. While in Vineyard Sound off Falmouth Heights, the skipper saw another racing yacht called the Swan, and a challenge was promptly made to see who could make it to Newport, Rhode Island, first. In the milder waters and breezes of Vineyard Sound, the Swan sailed ahead, but once in open water, with rougher seas and stronger wind, it was clear to all that the Sylph was the faster ship. The captain of the Swan, citing a concern about the weather, pulled into Tarpaulin Cove on Naushon Island and made anchor. The impact of this race was such that a yacht racing association staged a Centennial Race in 1935 to re-enact the race between the Sylph and the Swan, with this competition open to all cruising yachts.

The new owner of the Sylph put her into service as a pilot boat with the Boston ship pilots in 1836 before selling her to the New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots in October of 1837, as the newly formed organization built its fleet. She was registered in Newark and served with distinction as New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilot Boat No.1.The Sylph successfully escorted hundreds of vessels during her time in service, but she saw more than her share of tragedy as well.

In 1842, around 2:00 a.m., the Sylph was coming up New York Bay, abreast Robbins Reef Light off Bayonne, when a man named Curtis Lloyd, of Shrewsbury, N.J., “in a fit of delirium tremens, got overboard, and was heard crying out astern in the water. The boat was put about, and a small boat was launched, but before it could reach him he had sunk.” Lloyd left a wife and child. It is not known if Lloyd was a pilot boat crew member or pilot apprentice, but he is not believed to have been a pilot. What’s curious about this anecdote is that according to a story in the Journal of Commerce reprinted in a Vermont newspaper, “All of the pilots attached to the N. Jersey pilot boat Sylph are members of the Marine Temperance Society of this city. We hope that the same may soon be said of all our hardy pilots.” It would not appear that Curtis Lloyd was a member of any such society.

The Sylph was involved in many rescue efforts over the years, and there are newspaper accounts of saving survivors from wrecks, towing disabled vessels back to port, and in one instance, having pilot boat crewmembers boarding an abandoned ship and sailing her back to shore.

And the Sylph still engaged in the occasional race against other speedy yachts. On the day before Christmas, 1847, the Sylph and another pilot boat, the Anonyma, engaged the English yacht Iris in a ten-mile race in Broad Sound north of Boston; Sylph crossed the finish line two miles ahead of the Iris, and Anonyma finished 1.5 miles ahead, once again demonstrating not only the superior speed of the pilot boats but the skill of their captains. The race made national news in the U.S. and England.

On January 6, 1856, the Sylph was riding out a “tremendous gale” off Highlands when she was hit by a wave “which broke her rail, stove the boat, and swept overboard two of the pilots,” Charles White and James S. Johnson. By August, she was back in service again.

On or about March 2, 1857, fabled New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilot Boat Sylph, No. 1., was lost in a storm off Barnegat with four pilots, one apprentice, and five crew aboard. Nothing was recovered.

Sandy Hook Pilots in Time of War

Among the daunting challenges faced by George Washington and the leaders of the American Revolution was the utter lack of any kind of viable navy for the Patriots, while their enemy, the British, were truly the monarchs of the sea.

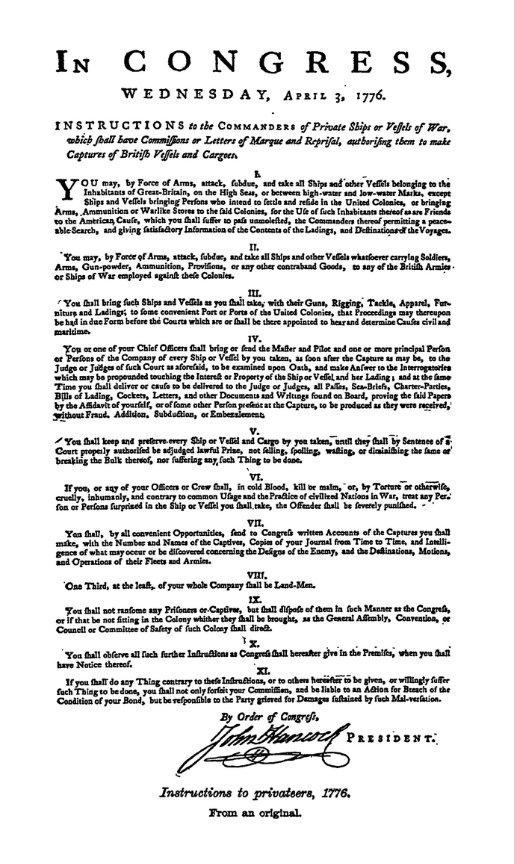

Lacking the logistical requirements to quickly construct vessels that could contend with British warships, Washington and others urged Congress to issue “Letters of Marque and Reprisal” that would license private citizens to capture any British vessel and its contents and receive a share of its value.

On Wednesday, April 3, 1776, Congress issued “INSTRUCTIONS to the Commanders of Private Ships or Vessels of War, which shall have Commissions or Letters of Marque and Reprisal, authorizing them to make Captures of British Vessels and Cargoes.” The document is signed by John Hancock. The document lays forth the rules for what these private citizens, who were called “privateers,” were allowed to capture; procedures for the handling of captured vessels, cargo, and persons aboard; restrictions and prohibitions such as disallowing the ransom of prisoners; preserving the captured vessel and not damaging it; and, a requirement that the ship’s primary officers be taken into custody for interrogation, and the ship’s pilot is specified. Article IV of the Instructions reads:

You or, one of your Chief Officers shall bring or send the Master and Pilot and one or more principal Person or Persons of the Company of every Ship or Vessel by you taken, as soon after the Capture as may be, to the Judge or Judges of such Court as aforesaid, to be examined upon Oath, and make Answer to the Interrogatories which may be propounded touching the Interest or Property of the Ship or Vessel and her Lading;

The notion of apprehending any pilot found aboard a captured British vessel shows how critically valuable the knowledge possessed by these navigators was at the time. Thus, this practice partially robbed the British navy of a valuable resource, but also provided the Continentals with vital information about just how well the British knew the American coast, its deepwater channels, major ports, defense installations, etc. And this practice also provided another reason for American pilots who were loyal to the king to think twice before offering their service to British vessels.

The first vessels to receive their commissions as privateers under the Continental resolutions and instructions were two tiny sloops named Chance and Congress, both former New York pilot boats sold to a Philadelphia syndicate. Chance, 45 tons burthen, was lightly armed with four carriage guns and 45 sailors under the command of Master John Adams, and Congress displaced 50 tons, with six carriage guns and 45 seamen under the command of Master George McAroy. Both sloops used Little Egg Harbor as their regular base of operations and achieved significant success capturing British vessels in the Caribbean.

There are other reports of pilot boats being converted into privateer ships during the Revolution, but it is not clear the extent to which pilots captained any of these vessels. Indeed, one can imagine that experienced pilots were badly needed by the Continentals performing their pilotage duties in the pursuit of liberty as much as privateer captains were needed to take prizes far away from home.

Cornelius Hatfield Jr. and his cousin John Smith Hatfield, of Elizabethtown, are examples of pilots dedicated to the Tory cause during the Revolution. It was said of Cornelius, who captained a company of New Jersey Loyalists, that “Few Jerseymen carried their toryism to the extent of this officer.” The two were involved in leading numerous raids against Elizabethtown and northern coastal New Jersey, including an unsuccessful attempt to kidnap New Jersey Governor William Livingston. Cornelius was apprehended and was facing trial as a spy when he escaped. John Smith Hatfield was arrested for murder, but was able to make bail, and fled to Canada, where Cornelius joined him after the war’s end.

War of 1812

The role of privateers in pilot boats in winning the American Revolution was a story told with pride for many years after these bold adventurers returned to their peacetime pursuits. So, when war with Britain broke out again in 1812, these private seamen once again were ready to answer their nation’s call. Edgar Stanton MacLay, author of the 1899 book, A History of American Privateering, wrote:

When the United States declared war against Great Britain, June 18, 1812, our navy consisted of only 17 vessels, carrying 442 guns and 5,000 men. Of these, only eight, in the first few months of the war, were able to get to sea. At the time hostilities broke out no American privateer was in existence; but the rapidity with which a great fleet of this class of war craft was created and sent to sea forms one of the most important and significant episodes in American history. At the first sound of war our merchants hastened to repeat their marvelous achievements on the ocean in the struggle for independence. Every available pilot boat, merchant craft, coasting vessel, and fishing smack was quickly overhauled, mounted with a few guns, and sent out with a commission to “burn, sink, and destroy.”

As word spread that war had been declared, a swift pilot boat hastened across the Atlantic to send a warning to American merchantmen in the ports of Sweden, Denmark, Prussia, and Russia, to move to safer waters to avoid capture by British warships.

Among the first pilot-boat privateers to go to sea in 1812 were the Black Joke, a sloop of five guns and 60 men under Captain B. Erenow, and Jack’s Favorite, with five guns and a crew of 80 men under Captain Johnson, both of New York. The Black Joke brought in two small prizes while Jack’s Favorite was more successful, having taken the schooner Rebecca, laden with sugar and molasses from Trinidad for Halifax, which was sent into New London; the brig Betsey, taken 250 miles west of Rock of Lisbon, with a full cargo of wine and raisins from Malaga for St. Petersburg valued at $75,000, and three sloops that were destroyed at sea.

Again, as in the Revolution, it’s clear that pilot boats played an important part in America’s victory over the British, but it is less clear the extent to which the pilots themselves took part in privateering.

American Civil War

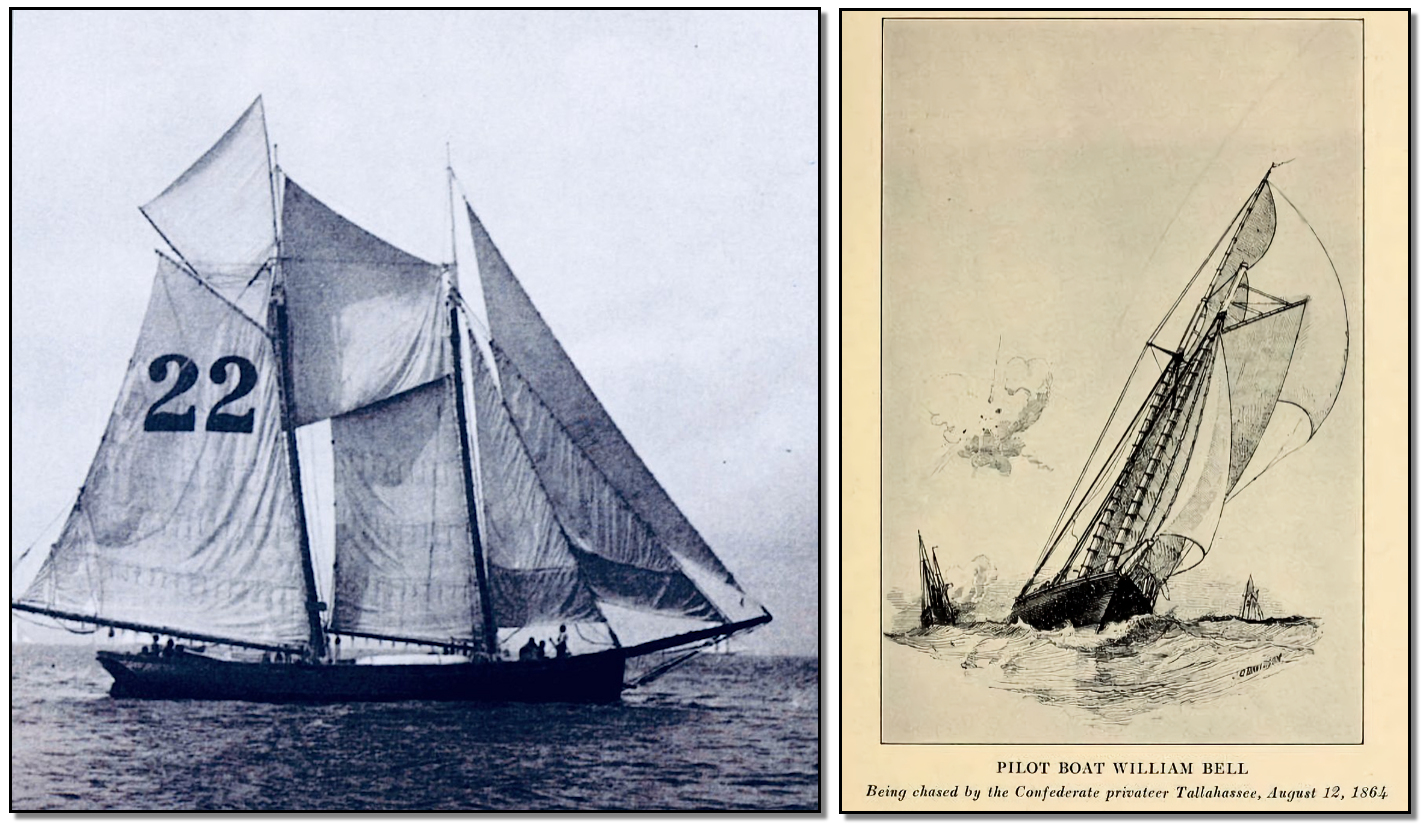

On August 12, 1864, the New York Sandy Hook Pilot boat James Funk, No. 22, was cruising southeast of Sandy Hook when it encountered a steamship flying the American flag. The James Funk raced toward the potential client vessel and put a yawl and pilot out to meet the ship. Upon being welcomed to the bridge, the pilot saw that a new flag had been raised, and realized that he had boarded a Confederate vessel, whereupon he was informed that his ship and crew were now prizes of war of the CSS Tallahassee.

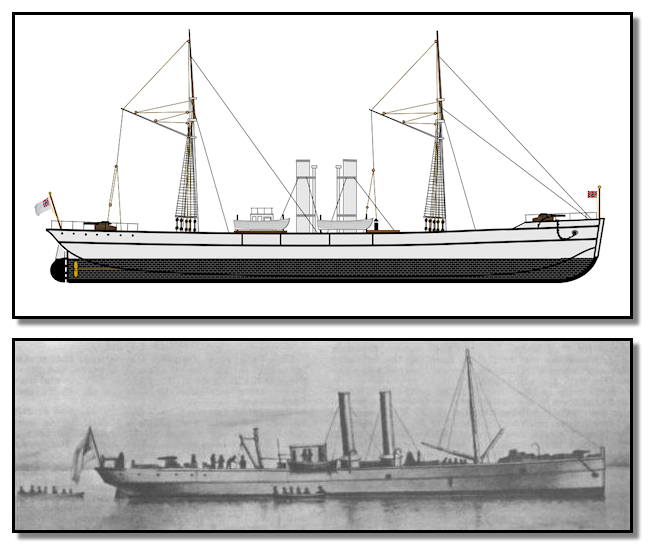

The CSS Tallahassee was a 220-foot-long double-masted twin-screw steamship used by the Confederacy as a blockade runner and for commerce raiding off the Atlantic coast. She was capable of a top speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) and was armed with three large cannons, one fore, one aft, and one amidships.

Another New York Sandy Hook Pilot boat, the William Bell, No. 24, saw the James Funk alongside the steamer and thought it unusual that the pilot boat was simply hove-to, meaning, sitting still in the water after coming about into the wind. Once pilots were transferred, pilot boats hoisted sail and went on their way, they did not remain with the client vessel. The William Bell sailed toward the James Funk, with the client vessel hidden behind the mainsail. They were within less than a mile when they realized that the James Funk was now flying the flag of the Confederate States of America.

The Bell, among the fastest of the Sandy Hook pilot boats, immediately took flight, putting up every sail available. The Tallahassee unfurled its own sails, and smokestacks billowed as the steam engines powered up. For a while, the Bell was able to stay just far enough ahead that a couple of cannonballs fired from a bow gun failed to convince the captain to stop. But eventually, as the steam engines gained full power, it became clear that the raider would overtake the pilot boat, which came around into the wind, ending the chase.

The William Bell was burned, and the James Funk was converted into a tender for the Tallahassee. Thirty crew members stayed with the James Funk in its new capacity while the other crew were paroled, meaning, made to swear not to take arms against the Confederacy, and set free on yet another pilot boat. But the captain of the Tallahassee had other plans for the Sandy Hook Pilots.

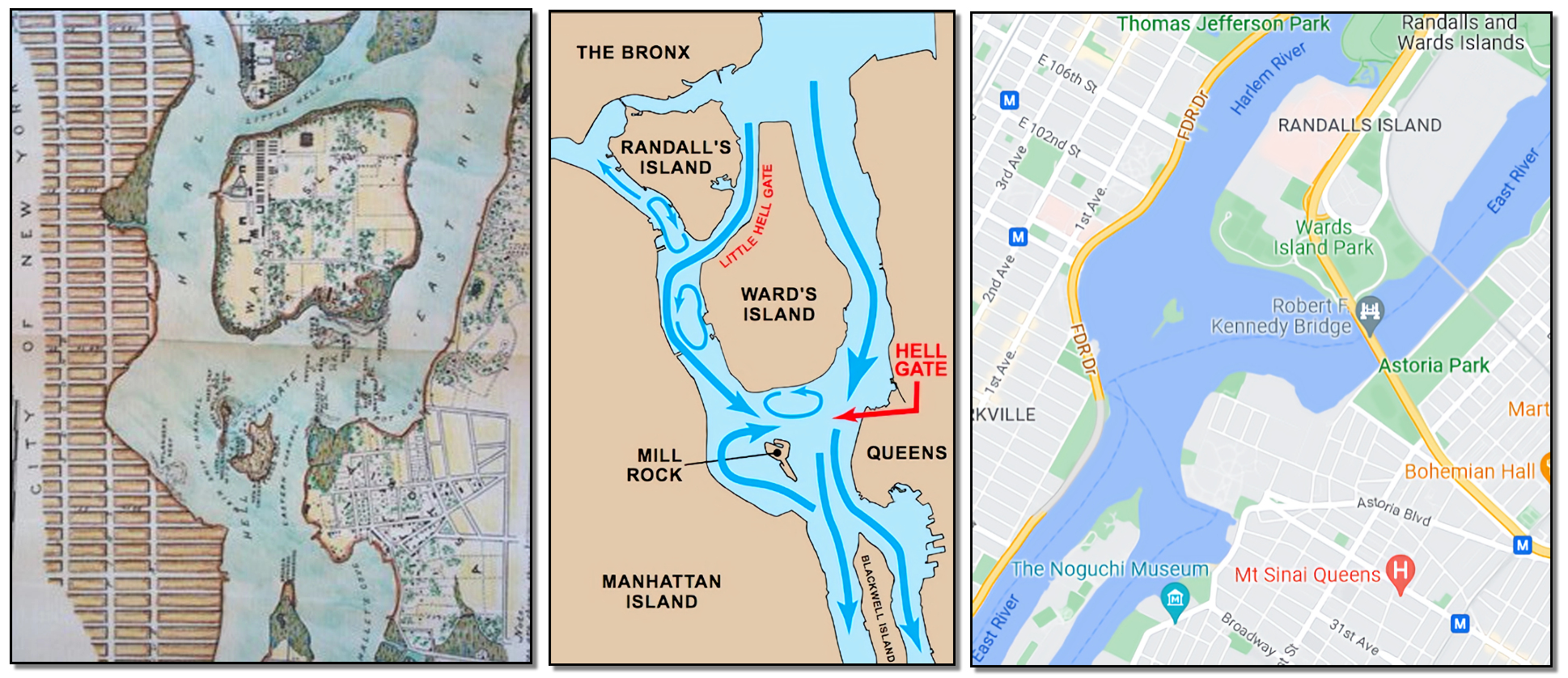

By the time the pilot boats approached the Tallahassee, she had already captured or sunk 26 Union vessels in the Atlantic. Her master, John Taylor Woods, grandson of U.S. President Zachary Taylor and nephew of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, had sailed the waterways around New York City prior to the war. His plan was to sail down the East River, setting fire to the ships and docks on both sides, shelling the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and then making an escape via Hell Gate into Long Island Sound.

Hell Gate is located at the point where the East River passes Manhattan, Queens, and the Bronx at the same time. The East River is, in fact, not a river at all, but a strait, a waterway that connects two larger bodies of water, in this case, New York Bay and Long Island Sound. With wider bodies of water on either side of Hell Gate, the changing tides create incredibly strong currents and whirlpools, making navigation extremely dangerous, especially under sail alone. A further hazard was the presence of a large underwater rock system, acres in size, that wrecked hundreds of ships and cost thousands of lives. By the time of the Civil War, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had begun the process of clearing these rocks from Hell Gate, but that process would not be complete for decades to come, and in the meantime, specialized pilots were a requirement for any large vessel attempting to pass it in either direction.

Master and Captain Woods knew this all too well and demanded that the pilots he’d taken prisoner help him with his plan, but the pilots aboard all either claimed to be unfamiliar with Hell Gate – a distinctly real possibility, as Hell Gate pilots were specialists in that passage while other pilots were not – or else they simply refused to cooperate. Ultimately, he was forced to abandon his plan. The Tallahassee was twice renamed by the Confederacy and deployed as a blockade runner before being seized by the British in London, where she was awarded to the U.S. Three years later she was wrecked off Yokohama, Japan, with 22 lost lives. Today, ships passing through Hell Gate are piloted by Sandy Hook Pilots.

The New Jersey Sandy Hook Ship Pilots Evolve from Sail to Steam

By the turn of the 19th century, the wonders of the industrial age had transformed maritime commerce significantly. Sail gave way to steam; more and better lighthouses and channel markers helped reduce collisions and wrecks. The evolution of the Sandy Hook Pilots mirrored that of maritime trade as a whole worldwide, but especially that of the ports of New York and New Jersey, at that time among the busiest in the world. From the New Jersey Commissioners of Pilotage Annual Report, 1898:

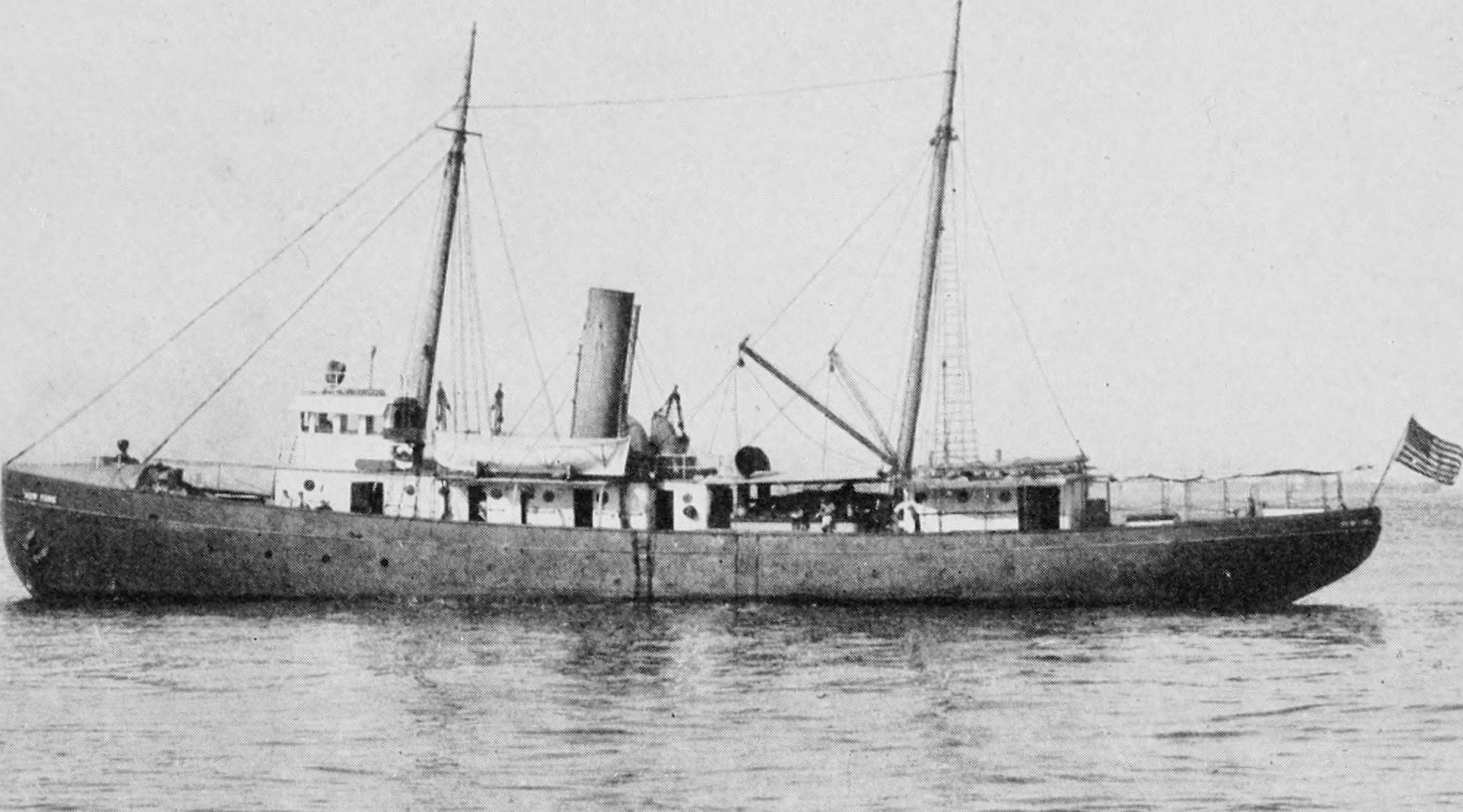

The change of the system and the addition of the new steam pilot boat New York, reduced the cruising radius of the boats to reasonable proportions, viz., sixty miles-thirty miles to the southward and thirty to the eastward – the distance divided into six stations of ten miles each, one pilot boat being allowed to each station; and at the outer end of the line, off the entrance to Gedney’s channel, the new steam pilot boat, built especially for this service, and known as the station boat, does her share of the work of placing pilots on incoming vessels, and takes off pilots from all outgoing ships; her position, about three miles outside of Sandy Hook, places her directly in the way of ships outward bound. A reserve pilot boat is stationed off Staten Island. The boats on the several stations move in rotation from station to station; those farthest to the east or south being first to sight the incoming ships are the first to be depleted of their pilots; as soon as this occurs, she leaves her station, notifies the other boats as she passes them bound into New York harbor, and anchors off Staten Island; meanwhile the other boats move out one station, leaving the station next to the steam pilot boat vacant until it is reached and taken by the boat from Staten Island with a full complement of pilots, which leaves the island immediately on sighting or receiving word of the depleted boat being bound in.

The pilots are divided into companies of seven men each, and to each boat are consigned three companies, whose round of duty is one company engaged in service on the pilot boat at sea, another in piloting ships out of the harbor, and the third in waiting at headquarters until the boat returns empty. The steam pilot boat does not take part in the rotation of the pilot boats, but keeps the same station continuously, except one day in every fortnight, when she come into New York for coal, water, provisions, &c.

The advent of steam-powered ships allowed the New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots to reduce their fleet of pilot boats from eight to three, with just one schooner remaining. The two new steam-powered pilot boats, New York and New Jersey, proved immediately to be vastly superior for the purpose of delivering pilots to and from client vessels.

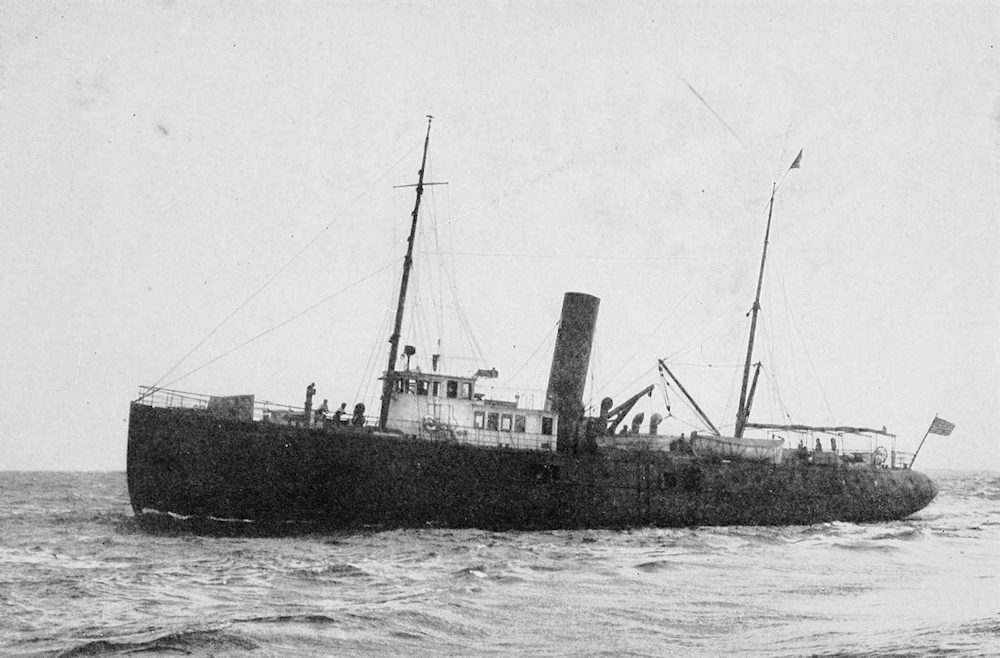

Built in 1897, the New York was the first steam-powered Sandy Hook pilot boat. After serving with distinction for decades, the New York was retired from pilot service in 1951.

The New Jersey was a steam-powered pilot boat built in 1902 for the unified New York and New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots Association. The New Jersey was so well constructed that she was used as an ice-breaking ram during the winter months. In 1914, after twelve years of service, the steamship SS Manchioneal rammed and sank her off Ambrose Lightship. The crew of 17 men was rescued by the Manchioneal. The New Jersey was replaced by the steam pilot boat Sandy Hook.

Sandy Hook Pilots in the World Wars

When the U.S. first began helping the Allies in the months before formally entering World War I, assistance came in the form of critically needed supplies bound for Great Britain. Thus, maritime commerce became a critical part of national security. When the U.S. entered the war, pilots were called upon to ensure that naval vessels also safely entered or departed New York Harbor. A particular new challenge emerged as pilots had to navigate the channels of New York Bay and Harbor, bringing across the bar merchant or naval vessels that had been disabled or damaged in battle.

Upon the U.S. declaration of war, virtually all 140 Sandy Hook Pilots volunteered for military service. They continued pilot duties, but now followed military mandates rather than those of port wardens. The prospect of encountering German submarines became a new deadly risk faced by pilots. At war’s end, Sandy Hook Pilots took the initiative to locate temporary anchorages for navy and merchant marine vessels returning after the war, awaiting re-assignment, mothballing, or a date with the scrap yard, so as not to have all these empty ships clogging the harbor as the nation returned to focusing on peacetime trade.

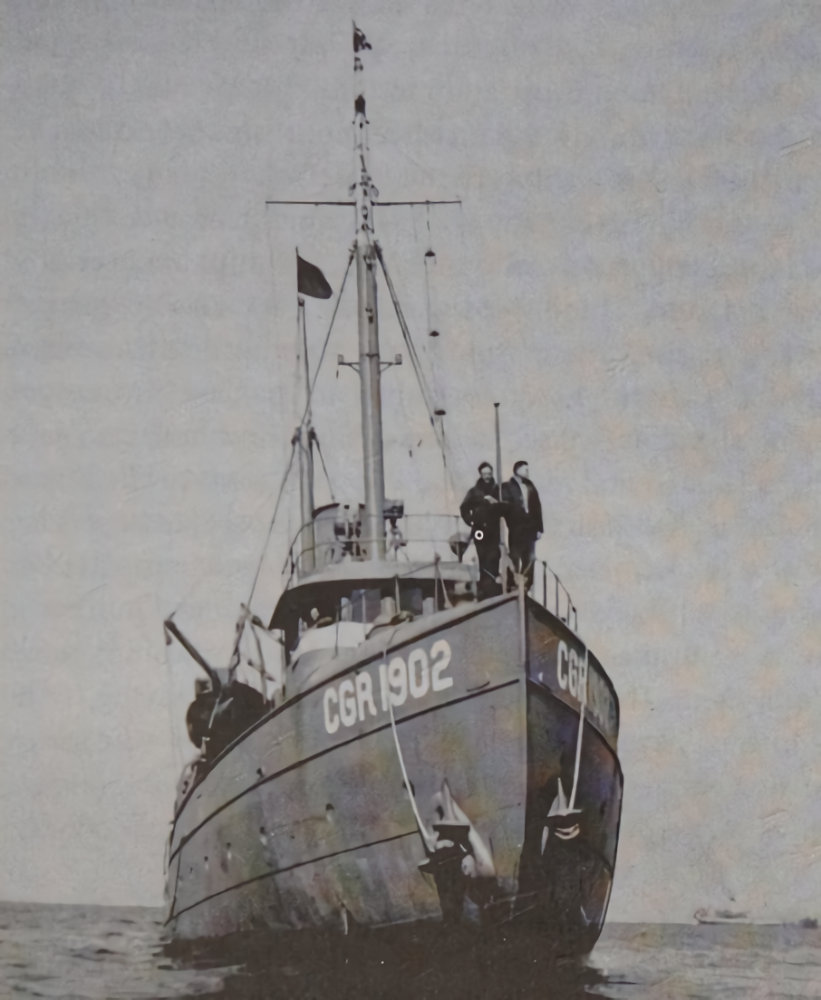

When the U.S. entered World War II, once again Sandy Hook Pilots volunteered, and they and their boats were detached to the Coast Guard Reserve. On April 26, 1942, New Jersey Pilot Boat New York was repainted battleship gray and designated as Coast Guard Reserve vessel CGR-1902, serving from June 1942 to November 1943. New Jersey Pilot Boat New Jersey became CGR-1903. Pilots now wore Coast Guard uniforms as opposed to their standard formal business attire.

During wartime, pilots took vessels of every conceivable type across the bar, including the luxury passenger liners HMS Queen Mary and HMS Queen Elizabeth, converted into troop ships, both of which could carry 15,000 passengers. Pilots took charge of moving entire convoys of ships out of port, along with invasion barges, battleships built at the New York Navy Yard, submarines, aircraft carriers, and every other type of vessel that was part of the war effort. In World War II, pilots also had brand-new potential hazards to consider: harbor defenses including underwater submarine nets and ship booms, or surface barriers.

As part of the anti-submarine defenses of New York City, a sophisticated system of radar and sonar stations was deployed. Unknown or unexpected vessels could be detected miles away, and a floating barrier was dragged across the channels preventing passage by surface ships. Underwater nets made of steel cable could likewise be closed if an unknown or unexpected submarine was detected. But for ship pilots, it was just one more factor to be taken into consideration for each and every ship passage.

The Risks of Being a Ship’s Pilot

How dangerous was it to be a New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilot? The annual reports from the New Jersey Commissioners of Pilotage typically included some information each year about pilots who had died the previous year, whether of old age, natural causes, or due to the many risks they faced on a daily basis in the line of duty.

Pilotage Commissioners annual reports from 1837 to 1852 are missing. We looked at the deaths of pilots in the line of duty from 1853 to 1895, when the New York and New Jersey pilots merged into one organization, and pilots began to enjoy a much safer working environment. Over those 42 years, at least twenty pilots died from a variety of causes (reports for several years within this span are also missing). From the Commissioners of Pilotage Annual Reports:

| Year | Pilot(s) | Cause of Death |

| 1853 | McNight Smith, Nelson Cole, Mathew M. Betts, and Thomas Scott | The NJPB Commerce, No. 3, foundered in a gale, all hands lost including four pilots; Thomas Smith, apprentice, son of McKnight Smith; Roger Clark, boatkeeper; plus three crew. Last seen January 12 leaving New York. Seventeen children lost a father that day. |

| 1856 | Charles White and James S. Johnson | On January 7, 1856, Pilots Charles White and James S. Johnson were “drowned off Highlands” after being washed overboard of the NJPB Sylph, No. 1. |

| 1857 | Daniel Lane, John H. Lane (brother), William Glynn, William Champlain | On or about March 2, NJPB Sylph, No. 1 was lost in a gale 17 miles off Barnegat. Also lost: an apprentice, the boatkeeper, four crew, and a passenger who had come along simply “for his health.” |

| 1858 | Unnamed pilot | Died from infectious disease contracted while on duty. Typical shipborne contagions of the mid-19th century included yellow fever, smallpox, cholera, and typhus, also known as “ship fever.” A single case of yellow fever aboard a ship could put all the passengers and crew under quarantine for as long as six months. |

| 1863 | William Ryder | Died of infectious disease contracted while on duty. |

| 1867 | Theophilus Beebe | On January 9, 1867, Beebe, the very first official NJ pilot, died in Jersey City, of heart disease, on the pilot boat Mystic. No records of Mystic. Beebe was pilot of NJPB Thomas H. Smith, No. 6. |

| 1871 | Joseph Hussey | On Jan. 26, 1871, Hussey, pilot of NJPB James W. Elwell, No. 7, died by shipwreck while at his post aboard the bark Kate Smith, off Little Egg Harbor. The Smith “went ashore during Wednesday night in the late terrible snowstorm and, being battered to pieces early Thursday morning by the maddening sea, eight of the crew, with the Sandy Hook pilot on board, were lost.” |

| 1872 | William C. Lucy | Died “by swamping of a boat off Sandy Hook, while in the discharge of his duty.” |

| 1876 | Robert D. Burnham | Died from infectious disease contracted in service. |

| 1875 | Thomas Leitch | Drowned November 8, 1875. |

| 1885 | Richard “Dick” Brown | Skippered racing yacht America; died from gangrene contracted while staying at his post in a winter storm. Also that year another pilot, unnamed, was “swept overboard from his boat and drowned at sea.” |

| 1886 | Robert B. Hall, and Charles Sylvester | Died “from diseases contracted through the hardships and exposure incident to their profession.” “Charles Sylvester, a Sandy Hook pilot, has been placed in an insane asylum. The first symptoms of insanity that he had shown were observed during the early part of the present week, while he was bringing in one of the large ocean steamers.” Sylvester, 42 years of age, “was taken to Bellevue Hospital last evening accompanied by his brother Robert…and who told Dr. Wildman that Sylvester showed signs of insanity while out on his boat NJPB Thomas S. Negus, No. 1., on Wednesday and his comrades would not permit him to go out to a vessel…his brother said that the symptoms of insanity were first noticed five months ago.” |

| 1892 | George B. Haveron, William W. Black | On April 24, Haveron, of NJPB E.T. Gerry, No. 2., died of pneumonia contracted “…during the terrible blizzard of March 1888, brought safely into port a barque named the Fawn, of which he had charge, and then contracted a chest affection that culminated in his death.” Black, 52, died September 27, 1892, it was rumored that he died of cholera contracted aboard an inbound ship, but his son said he died from “inflammation of the bowels, and that for years he had suffered from chronic dysentery.” |

The Modern-Day Sandy Hook Pilots: “Always on Station”

Today, the mission of the organization now formally known as the Sandy Hook Pilots, is “To provide pilotage service for the port of New York, New Jersey, Hudson River, Hell Gate and Long Island Sound.” Pilotage is provided on a 24-hour basis, 365 days a year, in all weather conditions and port circumstances.

Their fleet consists of two station boats, PB New York and PB New Jersey, carrying on the tradition of the very first steam-powered Sandy Hook pilot boats. The fleet also includes four America-class boats used for pilot boarding and transporting pilots two and from a pilot station. The Sandy Hook is slightly larger than the America-class boats and is used for similar tasks. The Association also operates a rigid hull inflatable craft used mainly as a rescue boat.

So, You Want to be a Sandy Hook Pilot?

The standards for achieving a ship’s pilot license have always been daunting; it takes years and years of learning, training, and experience aboard ships of all types and sizes. And there are numerous restrictions and behavioral guidelines, all of which are strictly observed.

For centuries, pilots utilized the guild system to recruit apprentices from talented young navigators and guide them through the process of becoming a pilot. This process resulted in many new pilots coming from the ranks of pilot families. There are numerous examples of father-and-son pilots, brothers who were pilots, and so on. Today, it takes 14 years of apprenticeship and on-the-job training to reach the status of Branch Pilot, more time than is required for either a doctor or lawyer. Requirements for apprenticeship include:

- U.S. citizenship

- Age 20-27

- Excellent physical health and eyesight

- Bachelor’s degree from accredited institution

- Passage of a battery of various intelligence and aptitude tests administered by an outside agency, and interviews

Many of those who enter pilot apprenticeship today are graduates from one of the state maritime colleges or the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, N.Y.

Pilot associations have emphasized diversity in recent years, after being an all-male bastion up until 1985, when Nancy Wagner became the first licensed female ship’s pilot in U.S. history. Captain Wagner retired in 2015 after 25 years as a pilot on San Francisco Bay.

Today, it’s estimated that only about 33 of the nation’s 1,100 pilots – three percent – are women. That number is growing, however, as is the number of African American pilots and licensed pilots of other ethnic backgrounds, as befits the multicultural nature of international maritime commerce. The Sandy Hook Pilots, as of 2008, claimed one female pilot and 13 “minority men.” They did not respond to numerous requests for comment and information from Monmouth Timeline.

It’s something that we here in Monmouth County all take for granted – as we watch the ships both big and little and in between come and go in and around New York and New Jersey – that it all goes so smoothly, but behind the scenes is a system of enormous complexity involving the most skilled and highly trained navigators, to help ensure the safety of all vessels using the Port of New York/New Jersey.

Sources:

Acts of the Sixty-First General Assembly of the State of New Jersey. (1837). Printed for the State, Trenton, N.J., P. 111.

America’s Cup Hall of Fame Induction Class of 1999: Captain Richard “Dick” Brown. Herreshoff Marine Museum, Bristol, R.I. Available: https://herreshoff.org/inductees/captain-richard-brown/.

Another Dreadful Shipwreck. (1837). The Herald, New York, N.Y., January 5, 1837, P. 2.

Annual Reports of the New Jersey Commissioners of Pilotage. (1853-1900). Collection of the New Jersey State Library. Available: https://dspace.njstatelib.org/handle/10929/46261.

Blunt, Joseph. (1832). The Merchant’s and Shipmaster’s Assistant: Containing Information Useful to the American Merchants, Owners, and Masters of Ships. E. & G. W. Blunt, New York, N.Y.

Captain “Dick” Brown. (1885). Star-Tribune, Minneapolis, Minn., July 5, 1885, P. 13.

Capt. Richard Brown’s Death. (1885). The New York Times, June 19, 1885, P. 2.

Coggeshall, George. (1856). History of the American privateers and Letters-of-Marque. Published by and for the author, C.T. Evans, Agent, New York, N.Y.

Correspondence of the Baltimore Sun. (1856). The Baltimore Sun, Baltimore, Md., January 11, 1856, P. 4.

A Crazy Pilot. (1886). The Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, Buffalo, N.Y., January 2, 1886, P. 1.

Death by Drowning. (1842). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., April 6, 1842, P. 2.

Disasters, &c. (1842). Boston Post, Boston, Mass., January 17, 1842, P. 2.

Duffy, Francis J. (2008). Always on Station: The Story of the Sandy Hook Ship Pilots. Purple Mountain Press, Fleischmanns, N.Y.

Eastman, Ralph M. (1956). Pilots and Pilot Boats of Boston Harbor. Second Bank-State Street Trust Company, Boston, Mass.

F. & J. Rives & George A. Bailey. (1848). The Congressional Globe, July 6, 1848, Vol. 18, Issue 56. Superintendent of Government Documents. City of Washington: Office of the Congressional Globe, P. 884.

Gleanings. (1842). Brooklyn Evening Star, Brooklyn, N.Y., April 7, 1842, P. 2.

Letter from Brigadier General William Maxwell to George Washington 27 February 1779. (1779). Founders Online, National Archives, Washington, D.C. Available: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-19-02-0310

Letter from Elias Boudinot to Thomas Jefferson, 11 April 1792. (1792). Founders Online, National Archives, Washington, D.C. Available: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-23-02-0345

Letter from George Washington to Brigadier General Samuel Holden Parsons, 23 December 1779. (1779). Founders Online, National Archives, Washington, D.C. Available: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-23-02-0537

Loomis, Alfred F. (1958). “Ah, Your Majesty, There Is No Second.” American Heritage, Vol. 9, Issue 5, August 1958.

MacLay, Edgar Stanton. (1899). A History of American Privateers. D. Appleton & Co., New York, N.Y.

Navigating a dream into a reality. (2019). The Northwest Seaport Alliance, March 29, 2019.

News summary. (1857). Brooklyn Evening Star, March 16, 1857, P. 2.

The Pilotage Question, As presented by the Committee of the Maritime Association together with the Proceedings at the General Conference Meetings with the Pilots. (1879). New York Maritime Association, New York, N.Y., December 9, 1879.

Nolte, Carl. (2018). Three Pioneering Women. Excerpt from The Sea Newsletter, Fall 2018, #77. Available: https://maritime.org/three-pioneering-maritime-women/.

O’Brien, Edward J. (1979). History of Compulsory Pilotage. Printed for the American Pilots’ Association, Washington, D.C., Second Edition. Available: https://cms3.revize.com/revize/americanpilots/APA%20History%20book.pdf.

Pilot Black’s Death. (1892). The Evening World, New York, N.Y., September 29, 1892, P. 5.

Russell, Charles Edward. (1929). From Sandy Hook to 62°. The Century Co., New York, N.Y.

A Sandy Hook Pilot Insane. (1886). The New York Times, January 2, 1886, P. 5.

Shomette, Donald Grady. (2016). Privateers of the Revolution. Shiffer Publishing, Ltd., Atglen, Penn.

Slosberg, Steven. (2019). Postscripts: How a Mystic man engineered the most stunning sports upset of the 19th century. The Westerly Sun, Westerly, R.I., August 18, 2019. Available: https://www.thewesterlysun.com/news/latest-news/postscripts-how-a-mystic-man-engineered-the-most-stunning-sports-upset-of-the-19th-century/article_efce9fee-c174-11e9-b132-23b8a5e8b919.html

A Statement of The Facts and Circumstances Relative to the Operation of The Pilot Laws of U.S. with Particular Reference to New York. (1848). R.C. Root & Anthony, Stationers, New York, N.Y.

Sylph. (2022). New Jersey Maritime Museum’s Shipwreck Data Base. Available: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/16PHJ82s2vviiYWxMJLkY21olzy4eXf9BpXSCEPTv0ZI/edit#gid=202885688Shipwreck Database 071922

Temperance among the Pilots. (1842). Vermont Chronicle, Bellows Falls, Vt., July 20, 1842, P. 3.

United States Coast Pilot. (1894). Atlantic Coast, Part V, From New York to Chesapeake Bay Entrance. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., Volume 1901, Second Edition.

Winters Jr., Edward C. (2004). Northwest 3/4 West: The Experiences of a Sandy Hook Pilot, 1908-1945. United New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots’ Benevolent Association, Staten Island, N.Y. Available: https://archive.org/details/northwest34weste0000wint/mode/2up?q=Northwest+3+4+West.

White, J. H., Thomas A. Edison, Paper Print Collection & Niver. (1903). Pilot leaving “Prinzessen Victoria Luise” at Sandy Hook. United States: Edison. [Video] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013604960/.

Wills, Matthew. (2019). When New Yorkers Burned Down a Quarantine Hospital. JSTOR Daily, September 19, 2019. Available: https://daily.jstor.org/when-new-yorkers-burned-down-a-quarantine-hospital/.

Wiser, Eric. (2020). The Outlaw Cornelius Hatfield: Loyalist Partisan of the American Revolution. Journal of the American Revolution, October 8, 2020. Available: https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/10/the-outlaw-cornelius-hatfield-loyalist-partisan-of-the-american-revolution/

The Wrecks on the New Jersey Coast. (1871). New York Herald, New York, N.Y., January 29, 1871, P. 6.

Please provide source for birth date for Captain Richard Brown.

Brown’s date of birth was included in an obituary first published by the New-York Herald, as reprinted here: Captain “Dick” Brown. (1885). Star-Tribune, Minneapolis, Minn., July 5, 1885, P. 13. Available:

https://www.newspapers.com/image/179061288/?terms=%22Captain%20%22Dick%22%20Brown%22%20&match=1

Newspaper reports of that era are not considered reliable. But that’s what’s been published.