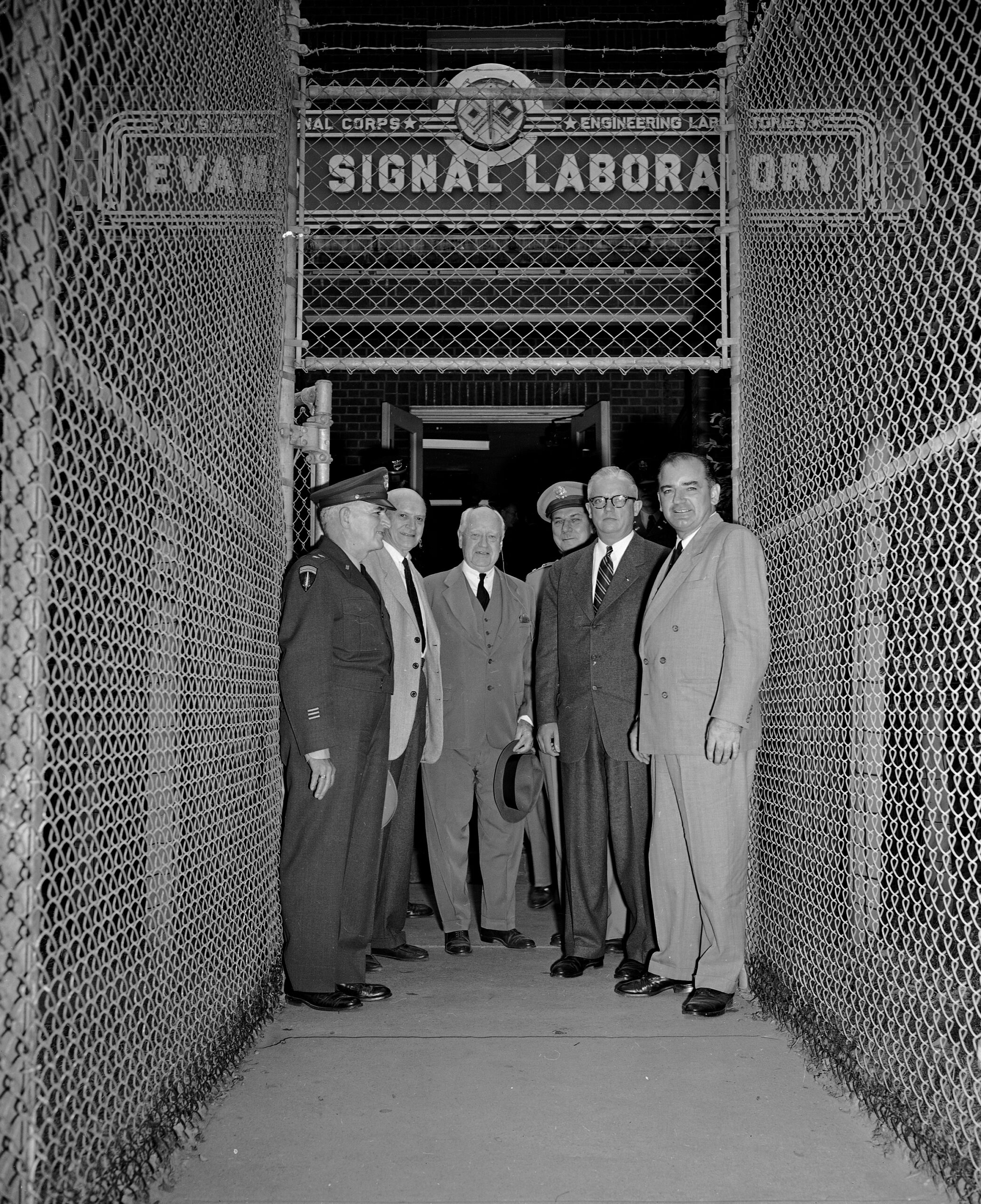

On October 20, 1953, U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, along with his chief aide Roy Cohn, arrived at the entry to Camp Evans, the ancillary base in Wall that was part of the World War II expansion of Fort Monmouth (pictured above). McCarthy and Cohn were there as part of a formal inquiry to investigate allegations that Julius Rosenberg’s communist spy ring still existed in the Signal Corps labs at Fort Monmouth, even after his execution earlier in 1953, along with his wife, Ethel.

Rosenberg, Joel Barr and Alfred Sarant were American civilian engineers employed by the U.S. Signal Corps, who were communist sympathizers. During World War II, the three successfully stole and transmitted to intelligence agencies in the Soviet Union thousands of pages of secret documents on defense technologies, mostly from defense contractors manufacturing weapons and systems designed by the Signal Corps. By 1942, Barr and Sarant left the Signal Corps to work at Western Electric, and in 1945 Rosenberg was fired for being a security risk. By 1946, all three were far removed from the Signal Corps. Rosenberg’s Manhattan Project espionage would become front-page news, but the successful efforts of the spy ring at Fort Monmouth and the Signal Corps defense contractors largely eluded counterintelligence agencies for years.

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was a Republican U.S. Senator from Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957; his nickname was “Tail Gunner Joe” for his war service. McCarthy first became famous in February, 1950, when he asserted in a speech that he had a list of “members of the Communist Party and members of a spy ring” who were employed in the State Department. His specifics with respect to the number of spies and where they were in government changed often, and were never substantiated, but created a frenzy for rooting out communists in an age where Americans lived in fear of a cataclysmic Soviet nuclear attack.

After winning a second term in 1953, McCarthy was made chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations. His committee first investigated allegations of communist influence in the Voice of America, the government international broadcasting agency, and then turned to the overseas library program of the International Information Agency, looking for works by authors he deemed inappropriate. Then they turned their sights on the U.S Army Signal Corps at Fort Monmouth.

At that time, the Army had already launched its own investigation into the state of security at Fort Monmouth. Base commander Kirke B. Lawton had significantly enhanced security; he was also known to be publicly critical of engineers who had attended what he considered to be “communist universities” such as Harvard, CCNY, Columbia, and MIT. He cooperated fully with McCarthy’s investigation.

McCarthy’s allegations were based on his claiming to have documentation and testimony from an East German scientist who had defected, and who had said that Soviet-bloc engineers had free access to Signal Corps classified documents and technology.

At Camp Evans, radar was being further advanced by the introduction of early computers to coordinate defenses against Soviet bombers. Transistors invented by engineers at Bell Labs in Holmdel were making radio and radar equipment smaller, lighter, and more precise. Priority research projects in 1953 focused on detecting Soviet nuclear tests, and development of electronic countermeasures. The detection center was the project that would cause a kerfuffle when McCarthy and Cohn decided to pay a personal visit to Camp Evans as part of their investigation.

Fred Carl, founder and director of InfoAge, the nonprofit group that has preserved Camp Evans as a museum and National Historic Landmark, wrote about this episode in the Asbury Park Press:

“When McCarthy approached the building with his staff, they were stopped by Camp Evans security. Only elected officials or those with top-secret clearance were allowed in, but McCarthy insisted that the project should not be classified top secret, and ordered the security personnel to allow his staff in. A heated argument followed, during which security reminded the senator they had authority to shoot anyone attempting to enter the building without proper clearance.”

With McCarthy at the time of the visit were Major General Lawton, base commander; U.S. Senator H. Alexander Smith (R-N.J.); Rep. James C. Auchincloss (R-N.J.); Major General George I. Back, chief signal officer, and Secretary of the Army Robert T. Stevens. They were all admitted. Among those excluded was McCarthy’s chief aide, Roy Cohn, who angrily vowed before witnesses that he would get the Army for the affront.

Those who were allowed in were given a three-hour tour. “As far as I can see,” McCarthy said, “there is no morale problem among loyal employees and they are very happy that the few bad apples are being thrown out.” Speaking of security at Camp Evans, McCarthy said, “It was sloppy beyond words. It was extremely dangerous. A thing of this kind could be of world wide importance.”

After the tour, McCarthy and Cohn held a hearing at Fort Monmouth, still focusing on the allegation that members of the former Rosenberg spy ring were still operating there.

McCarthy and Cohn used their standard ploys…unsubstantiated claims to having a list of names of subversives, accusations made by shadowy unnamed foreign sources, etc., as the basis for this inquiry. More than 100 people testified, with many witnesses being called multiple times. Personnel were never allowed to confront their accusers.

At that time, according to Army Secretary Stevens, 15 employees at Fort Monmouth had by then been identified by either the Army’s investigation or McCarthy’s investigation as security risks, and suspended.

Following McCarthy’s visit to Fort Monmouth, more hearings were held in New York City. By the time the hearings concluded, the senator from Wisconsin had ruined dozens of careers and lives with no evidence of real wrongdoing. Signal Corps employees lost their jobs for such offenses as attending a benefit rally for Russian children, or belonging to a labor union local thought to be subversive. Being a member of the American Veterans Committee or American Labor Party, or even allowing an employee to read the Daily Worker, the publication of the American Communist Party, were all grounds for suspension.

Ultimately, 42 employees of Camp Evans, mostly engineers, were suspended for posing security risks. Forty were eventually reinstated, two resigned. All of the reinstated received back pay. The last six to get their jobs back finally rejoined the workforce in 1958. It did not escape observers that 39 of the 42 people who lost their jobs were Jewish, with those at the time concluding that the base had a pervasive anti-Semitic and racist culture.

McCarthy’s Baseless Attacks On The Army Lead To His Downfall

On April 22, 1954, U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, who was accustomed to leading investigations based on spurious allegations, became himself the target of a Senate investigation, by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, usually chaired by McCarthy himself.

Earlier that year, the U.S. Army had accused McCarthy and his chief counsel, Roy Cohn, of improperly pressuring the army to give favorable treatment to G. David Schine, a former aide to McCarthy and a friend of Cohn’s; Schine was then serving in the army as a private. McCarthy claimed that the accusation was made in bad faith, in retaliation for his questioning of certain witnesses the previous year related to unfounded charges of alleged ongoing espionage at Camp Evans, the ancillary facility of Fort Monmouth. The Senate was given the task of adjudicating these conflicting charges. The Army–McCarthy hearings convened , and lasted for 36 days, broadcast live on national television with an estimated 20 million viewers.

During these hearings, on May 5, 1954, McCarthy publicly asserted yet again that Communist infiltration was rife within the U.S. Army Signal Corps at Fort Monmouth, specifically Camp Evans. McCarthy was questioned about a letter he claimed to have received with 34 names of people connected with the Rosenberg spy ring, and claimed that “17 of them were still working at the radar laboratory at the time our investigation commenced.” He referred to Fort Monmouth as a “very very bad security situation” and that the communist infiltration was “restricted almost exclusively to Fort Monmouth.”

The hearings would become famous for an exchange that would many historians would later mark as the beginning of the end of McCarthy’s public career. The incident was an exchange between McCarthy and the army’s chief legal representative, Joseph Nye Welch. On June 9, the 30th day of the hearings, Welch challenged Roy Cohn to provide U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. with McCarthy’s list of 130 Communists or subversives in defense plants “before the sun goes down.” McCarthy then said that if Welch was so concerned about persons aiding the Communist Party, he should check on a man in his Boston law office named Fred Fisher, who had once belonged to the National Lawyers Guild, a progressive lawyers association.

In an impassioned defense of Fisher, Welch responded, “Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness…” When McCarthy resumed his attack, Welch interrupted him: “Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?” When McCarthy once again persisted, Welch cut him off and demanded the chairman “call the next witness.” The gallery erupted in applause, and a recess was called.

By now, the nation and leaders of both political parties had grown weary of McCarthy’s endless accusations, which had never panned out. On December 2, 1954, the Senate voted to “condemn” McCarthy on two counts by a vote of 67 to 22, making him one of the few U.S. senators ever to be censured in this fashion.

McCarthy remained in office, but despite being shunned by colleagues and the press, nevertheless continued to speak against communism and socialism until his death at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Md., on May 2, 1957, at the age of 48. His legacy would be defined by a term popularized during his reign of fear-mongering, “McCarthyism,” a phrase still in vogue to describe harsh baseless attacks on people’s reputations, a synonym for “witch hunt.”

The legacy of the U.S. Army Signal Corps at Fort Monmouth in World War II, aside from the painful chapter of Joel Barr, Julius Rosenberg and Alfred Sarant, is an awe-inspiring list of technological innovations, systems, inventions and military breakthroughs that continue to influence not only America’s military defense, but our daily lives as well.

SOURCES:

BIG ROLE IN SOVIET COMPUTERS LAID TO ROSENBERG ASSOCIATE. (1983). Associated Press in The New York Times, September 19, 1983, Section B, P. 14. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/1983/09/19/us/big-role-in-soviet-computers-laid-to-rosenberg-associate.html?searchResultPosition=2

Carl, Fred. (2003). McCarthy’s communist hunt unraveled at Wall facility. The Asbury Park Press, November 10, 2003, P. B1, B3.

Executive Sessions of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, Eighty-third Congress, First Session, 1953. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., vol. 3, 2705, 2003. Available: https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/Volume3.pdf

Kling, Andrew A. (2012). The Red Scare. Lucent Books, A part of Gale, Cengage Learning. Gale eBooks. Available: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2349300001/GVRL?u=monmouth_main&sid=GVRL&xid=1d1118c3. (library membership required).

Lordan, Frank. (1953). Soviets Bragged Of Access To Material At Evans Lab. The Daily Record (Long Branch, N.J.), October 23, 1953, P. 1, 3.

McCarthy Pins Blame on HST. (1953). The Daily Record (Long Branch, N.J.), October 23, 1953, P. 1.

McCarthy Visits Evans Laboratories. (1953). The Asbury Park Press, October 23, 1953, P. 1.

Radosh, Ronald & Milton, Joyce. (1983). The Rosenberg File: A Search for the Truth. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, N.Y.

Staff of the Historical Office. (2008). A History of Army Communications and Electronics at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey 1917-2007. Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Plans, U.S. Army CECOM Life Cycle Management Command, Fort Monmouth, N.J. U.S. Government Printing Office, available: bookstore.gpo.gov.

Transcript of Special Senate investigation on charges and countercharges involving: Secretary of the Army Robert T. Stevens, John G. Adams, H. Struve Hensel and Senator Joe McCarthy, Roy M. Cohn, and Francis P. Carr. Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate, Eighty-third Congress, second session. (1954). Available: https://archive.org/details/specialsenateinv20unit/page/n3.

Usdin, Steven T. (2005). Engineering Communism: How Two Americans Spied for Stalin and Founded the Soviet Silicon Valley. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Usdin, Steven T. (2007). Tracking Julius Rosenberg’s Lesser Known Associates: Famous Espionage Cases. Central Intelligence Agency Library, April 15, 2007. Updated June 26, 2008. Available: https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol49no3/html_files/Rosenberg_2.htm

Leave a Reply