On October 5, 1781, Captain Adam Hyler of New Brunswick led yet another attack on British and Loyalist merchant vessels in Raritan Bay; on this occasion, he and his oarsmen captured five valuable British ships within a quarter mile of the British guard ship at Sandy Hook without losing a man or boat.

The Rise of American Privateering

By the end of summer of 1781, the French had joined the American side against the British, and the British fleet was forced to engage the French in the Battle of the Chesapeake, where the French gave them a proper drubbing.

As a result, during this time, the British Navy presence in Raritan Bay and the greater New York Harbor region was considerably reduced from previous levels. The lack of armed protection left British merchant ships and other vessels vulnerable to attacks by militia as well as privateers. “Privateers”were essentially licensed pirates, given documents by one country permitting the seizure or destruction of ships and their cargoes of another specific country. With the 13 colonies having a negligible navy of about 64 ships with 1,200 guns, the use of privateers throughout the colonies expanded the seagoing fight against the British with an additional 1,700 ships and 15,000 guns.

The year 1781 was the culmination of privateer attacks in Raritan Bay. Among the most prominent leaders of these engagements was Captain Adam Hyler. Born in 1735, in Wurttemberg, Germany, little is known of Hyler’s life before he began privateering. But over the course of 1781-82, he lead eight separate attacks against the British, each one more audacious than the last. And he did this using rowboats.

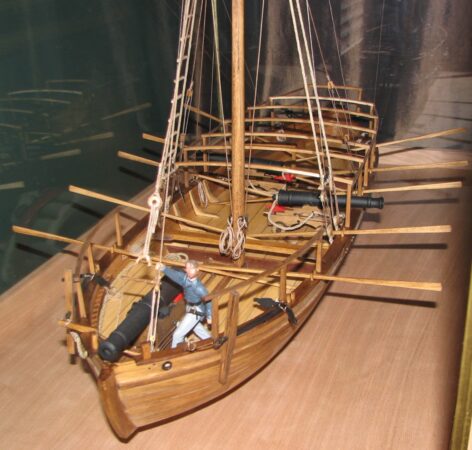

Hyler specialized in using whaleboats, sturdy vessels that often had a dismountable mast and could be outfitted with guns, powered by from eight to 16 oarsmen (the photo above shows a model of a whaleboat of the type that Hyler might have used). Whaleboats had the advantage of being able to navigate waterways with far less regard for wind and tide and currents relative to ships relying on sail alone. It was said Hyler’s men could propel their whaleboats as fast as 12 miles per hour, enabling fast attacks and quick escapes. Cloths were used to muffle oars, making it especially difficult to defend against these stealthy surprise attacks.

Hyler’s first engagement as a privateer may have been In November, 1780, when he led his whaleboatmen on a successful foray along the Staten Island coast, capturing the sloop Susannah from her anchorage. On August 5, 1781, Hyler went to Long Island, where he “marched three miles and a half into the country, and made Captain Jeromus Lott, a Lieutenant-Colonel of Militia, and one John Hankins, a Captain of a vessel, prisoners, and brought them safe to New Brunswick,” along with several others, to be used in prisoner exchanges.

Newspapers of the day, both American and British, were filled with accounts of his colorful exploits in the harbor and his raids into Kings County and around Sandy Hook. He was described by Loyalist newspapers as a deserter from the Royal cause, which makes his heroism that much more remarkable, because if he was a deserter, if caught, he faced a hangman’s noose.

His gunboat Revenge was often accompanied by other whaleboats and small craft. He depended entirely on stratagem and surprise. “Rarely did their victims know of their proximity until they saw a pistol or cutlass at their throat.”

Hyler had great success capturing British vessels, which he would bring back to New Brunswick via the Raritan River, to be sold by the Admiralty Court, but if that was not possible, he would either blow up the enemy ship or set it afire. He was not above ransoming a valuable boat for cash to return it untouched to its owners.

A Smart Conflict on October 5, 1781

On the night of October 5, Hyler headed out into Raritan Bay with the Revenge and two whaleboats, and crept up to the unsuspecting British vessels, some of which were armed, and most of whose crew was ashore. After “a smart conflict of fifteen minutes” Hyler’s men had taken control of all five vessels without a shot fired.

The onboard crew of the seized vessels were allowed to escape via longboats to Sandy Hook, where they took up guns and attempted to drive off Hyler’s men, but Hyler completed his attack without losing a single man or whaleboat. He seized wheat and cheese belonging to the notorious Loyalist Captain Richard Lippincott, who was responsible for the lynching of Monmouth Militia Captain Joshua Huddy. He also took guns, powder, fuses, dry goods, sails and rigging. Wind and sea conditions made it impossible to take the ships back to New Brunswick, so Hyler burned all but one, which he spared owing to the presence of a woman and children on board.

After capturing the five British ships on October 5, Hyler kept up his attacks. On October 18, 1781, he seized a sloop and two schooners off Sandy Hook. Six days later, Hyler captured six men in a raid on Refugeetown, near Sandy Hook Lighthouse. On November 10, 1781, Hyler captured the British cargo ship Father’s Desire in New York Harbor. Once weather allowed, he resumed privateering in 1782; on May25, he lead his men against the British in a combined naval and land action in which he attempted to kidnap Captain Lippincott from his stronghold in New York City. In June of 1782, Hyler destroyed several boats during another raid. And finally, on July 2, 1782, in his last known attack, Capt. Hyler destroyed a British privateer ship near Sandy Hook.

Hyler died on September 6, 1782, “after a tedious and painful illness” and was buried with military honors in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of the Reformed Dutch Church at New Brunswick. Rumors arose that he had been poisoned by a secret Loyalist tavern server, but historians believe that he died from complications of an accidental self-inflicted wound. The records of The First Reformed Church in New Brunswick show that one “Adam Huyler” is buried in the cemetery there in an unmarked grave, but the exact location of his burial is unknown. Given that surnames were regularly misspelled in those times, and “Huyler” is a common form of the name “Hyler,” it is believed that this is n fact the great privateer captain’s final resting place.

Sources:

Koke, Richard J. (1957). War, Profit, and Privateers. New York Historical Society Quarterly, July 1957, Chapter 2, P. 197 – 199.

Privateers and Mariners in the Revolutionary War. (2001). American Merchant Marine at War. Available: http://www.usmm.org/

Shore Vignettes (1968). Living Precariously at Sea. Asbury Park Press, January 21, 1968, P. 15.

The Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia), 16 October 1781, p. 3. Available:

http://www.doublegv.com/ggv/battles/whaleboat.html

Privateers of the Revolutionary War – Part 2. (2015). New Jersey Maritime Museum. Available:

https://njmaritimemuseum.org/privateers-of-the-revolutionary-war-part-2/

Photo courtesy New Jersey Maritime Museum.

According to dna he was my fifth great grandfather. I have been trying to find more information about him, so thank you for this.

Adam is my 5 great grandfather also, would love to compare notes

Im doing research on ellen s low, the ony female lighthouse keeper of LBI’s first barnegat lighthouse. I believe Ellen is his granddaughter through Adams son William. Id be very interested in any information you have about her!

We do not have any information because Barnegat is in Ocean County and with certain exceptions, we try and leave their entire history to them. Before 1850, all of Ocean County was part of Monmouth County and the Monmouth County Historical Association tracks the history of places like Barnegat up to 1850, so I would check with them in addition to the Ocean County Historical Society.