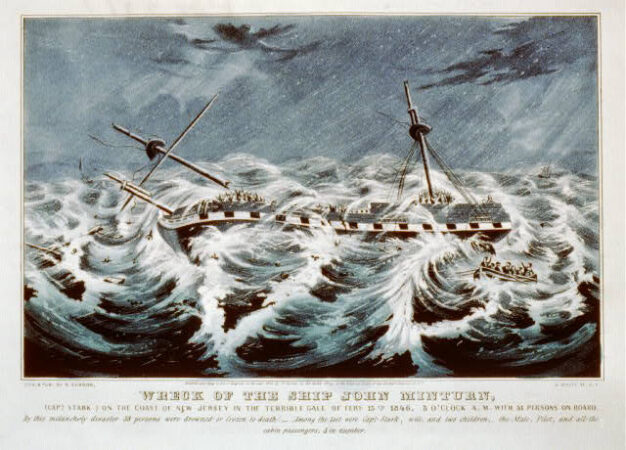

On February 15, 1846, a severe storm caused a number of horrifying shipwrecks along the northeast coast that were a shock even to a nation long accustomed to maritime disasters. One of these was the John Minturn, a three-masted packet ship bound for New York from New Orleans. The Minturn made it all the way to Sandy Hook, near the entrance to New York Harbor, where safe mooring awaited. Instead, the storm blew the ship back southward and out to sea. The captain tried to run the ship aground on the beach off Mantoloking, in what is today Ocean County, to save passengers and crew, but ran hard into a sandbar. Ultimately, 38 people from the John Minturn perished that day, and other shipwrecks from that storm resulted in 22 more lives lost.

The Minturn was in our waters during a period when the business of ship’s pilotage was a matter of intense competition between the New York Sandy Hook Pilots and the New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots. Law allowed a pilot from either group to solicit client vessels and place a pilot on board to command the ship into the port via the complex local channels. The nature of this competition had resulted in veteran ship captains often having partisan views and refusing pilots from one or the other group. Despite the threatening weather, Captain Stark refused to take on a New York pilot.

<So it was that the captain and master of the John Minturn, Dudley Stark, found himself facing bad weather, but none of his preferred New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilot boats were in the vicinity. As to why Captain Stark might have had a preference for New Jersey pilots, it could stem from his very upbringing.

<Stark was born in Mystic, Conn., and one day he and four other youths ran away to sea. All of them became ship’s captains. One of them was Richard “Dick” Brown, perhaps the ultimate New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilot, a man famous for having skippered the racing yacht America on her historic voyage to England and her victorious turn in the Royal Squadron Regatta. Subsequent races to challenge the primacy of the America became known as the America’s Cup series.

As the day went on and the weather worsened, Stark finally relented and took on a New York Sandy Hook Pilot named Thomas Freeborne. As is not only customary but compulsory by law, Stark, as the ship’s master, handed over control of the John Minturn to the pilot, who served as captain for the remainder of the voyage through local waters.

That evening, when the hurricane hit, the Minturn was still about four miles off the coast, seeking to do whatever it took to fight the winds blowing her towards shore. Captain Freeborne tried to put up just a small sail, just enough to bring the ship around into the wind and attempt to beat a tack away from shore. They tried topsails that were new, and should have been stout, but they were blown to ribbons. On the next tack the foresail split, and the ship lost more ground. Finally, the headsails also split and the ship headed for the shoals.

Seeing the fight was over, Freeborne tried to maximize the possibility of saving the lives on board by striking land bow first. At 3:15 she finally struck the outer bar, then struck again, breaking the ship and bringing it broadside to the beach, heeling away from it. Freeborne offered his coat to Captain Starks’ wife, but they too perished. Freeborne was buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn. In recognition of his heroic fight against all odds, a statue called The Pilot’s Monument was erected by the New York Sandy Hook Pilots in 1847. Afterwards, Freeborne was heralded as a hero.

Initial news coverage of the Minturn disaster in the U.S. revealed no allegations of impropriety. But in England, another story was being told. A highly regarded outlet, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, published the following account of the Minturn wreck:

Particulars, so far as they are known…reported at Lloyds on Monday.

Between eleven and twelve o’clock at night, a boat was put off to rescue those who were clinging to other pieces of the wreck, two of the crew, and four of the steerage passengers; and after almost insurmountable difficulties they were preserved, although, as may be readily conceived, reduced to the last stage of exhaustion.

On the following morning, at daybreak, they were brought ashore, when the beach was lined by the inhabitants of the neighboring villages. Amongst them were a desperate gang of wreckers, who plundered every body that was washed up from the other pieces of wreck. Several of the passengers were known to have had a large amount of money about them.

The term “wreckers” was used for millennia to refer to coastal residents in shipwreck-prone areas of the world. They earned a horrible reputation, mostly unfairly. Click here to read about the early history of wreckers in New Jersey. New York newspapers at first defended the Monmouth County locals, but re-stated the old allegations from the 1834 land pirates hoax story, presenting them now as established fact:

The district of Squan is under the charge of one of the most energetic and humane wreckmasters on the coast, who has great experience. Since the Barnegat pirates were broken up, there are few robberies, and the wreckers are daring in saving lives.

But soon, other accusations emerged, such as this in The New York Herald:

It appears that those who lost friends in the late gale, on the coast of New Jersey, were compelled to pay ten dollars for each body cast lifeless on Squan Beach, to the local authorities in that vicinity.

A story in the New York Evening Post, attributed to the Newark Daily Advertiser, with the headline, “The Wreckers of New Jersey,” stated:

It would seem from all accounts before us that the robberies were confined to the shoremen about the wreck of the ship John Minturn, and that outrages in this case were not so gross as they have been reported to be. The reports were the more readily credited from the remembrances of the infamous scenes enacted there just eight years earlier.

Once again, defending the reputations of the current locals meant tarnishing those of just eight years earlier. But things would get worse.

The New York Daily Herald published a story headlined, “Interesting Details of the Late Storm – Inhospitality – Barnegat Pirates,” that leveled very serious accusations. It said Barnegat wreckers had boarded the Minturn at night while it foundered in the heaving seas and broke into passenger and crew trunks and chests, stealing everything, including the captain’s watch.

Further, survivors of the Minturn accused Barnegat locals of making no effort to render aid to the ship and stated that families of those who died were then charged ten dollars if they wanted to recover the bodies of their loved ones.

Outrage was immediate and widespread. Reports came out claiming that surf boats and other means for saving those on the Minturn were available but the people on shore “showed a most culpable disregard of all the dictates of humanity, and made no attempt to render aid to the crews.”

All this was soon shown to be spurious. On April 24, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle ran a story attributed to the Newark Daily reporting that the Minturn captain’s chronometer, said to have been stolen by locals, had washed up on the beach, “showing conclusively that this charge, like other imputations upon the characters of our citizens here, was utterly false.” The allegation that money was exacted for delivery of bodies turned out to be an official request for three dollars from the family of each victim, who could so afford, to help pay burial costs. No one who could not pay was asked to do so. Indeed, Monmouth County incurred thousands of dollars in unreimbursed burial expenses annually from shipwreck victims.

Contrary to press reports, John S. Forman was the wreck-master on duty at the time of the John Minturn disaster. A meticulous record keeper, it is odd that only one file exists from Forman’s marine salvage notes relating to the Minturn. It is a grisly accounting of payments made to Monmouth County locals who assisted in removing and burying corpses from the wreck.

The statement of one surviving crewmember made no mention of any boarders, and he claimed that the ship was breaking into two, with one half sinking into the sea, at the time the wreckers were said to be plundering chests and trunks. The crewmember was of the opinion that if the people on shore had more courage and had made more of an effort, that many, if not all, lives could have been saved. People aboard ships in mortal peril tended to perceive fewer risks from rescue attempts than those who were safely ashore.

This is a point that is not contended. In the aftermath of the Minturn disaster, it would come to light that the resources being devoted to shore-based rescue efforts were minimal, and often ineffective. Men like Forman had the authority to recruit and pay people to assist with wrecking, but even though the law provided for penalties for those who refused his call to action, he could really not force anyone to do so, thus, he could find himself at times helpless to render aid. Over the next 30 years, the acts of Congress that eventually led to the creation of the U.S. Life-Saving Service were a direct result of the acknowledgment that the use of volunteers and underpaid and untrained local appointees was unsustainable. For every stalwart John S. Forman, there were disinterested and incompetent wreck-masters, and so the level of effort and effectiveness of aid varied from place to place.

A Formal Investigation

Local newspapers finally began to rise to the defense of the shoremen, and soon politicians took an interest. A state senator from Hunterdon County introduced a resolution into the Senate of New Jersey in Trenton condemning the neglect of survivors and plundering of bodies, and called on the governor to initiate an investigation into the matter. Text of the resolution included the following:

Either the ‘Barnegat Pirates’ are the most infamous scoundrels upon the face of the earth, or they are a much injured set of men.

Whereas, it is represented in the public journals that at the time of the late distressing shipwrecks of the John Minturn and other vessel on the New jersey coast, some persons on the shore neglected and refused to render relief and assistance to the perishing passengers and seamen, plundered the bodies of everything valuable found upon them, and in other cases exacted money for the delivery of bodies.

Governor Charles C. Stratton appointed a committee to investigate all of the wrecks from the storm of February 15, 1846 in New Jersey. Two days after being appointed, the commissioners met at Freehold to start the investigation. It is logical to assume that Forman’s related files, being important exhibits for the committee, may have ended up there and were subsequently kept with the other marine salvage records. That may explain their absence from the MCHA archives today.

From Freehold, the commissioners then traveled to Sandy Hook and proceeded south, visiting the site of each of the ten major wrecks along the Monmouth County coast resulting from that storm. They interviewed 36 witnesses, including surviving captains, crew and passengers from the various wrecks, along with locals accused of crimes. In several cases, captains or crewmembers who survived that day and had heard about the investigation made a point of appearing before the committee to tell their stories of survival and heroic rescue efforts by locals under daunting circumstances.

On March 25, 1846, the committee’s findings were as follows:

We therefore report to your excellency that the charges in the resolution under which we act…are accordingly to the best of our judgment upon the evidence, each and every one of them untrue; that here are no inhuman and guilty actors therein to be punished, and that the state ought to be released from the odium of such barbarity.

During this time, some efforts were made in print to defend the Monmouth County coastal people, but such efforts often seemed to exonerate some, but cast aspersions on others, at the same time. Examples of this include:

Indeed it has been repeatedly proved that where robberies were committed it was either by the sailors from the wreck or by the men sent down by the underwriters.

The essential point being that crimes were definitely committed, when in fact, the investigation found that only one theft was reported from the ten wrecks, that being a chest valued at $300. And this:

If vessel and cargoes had never been insured for more than they were worth, the character of pirate would never have been given to the Jersey Shore people.

But vessels and cargoes were often uninsured, or over-insured, and so therefore this statement concludes the Jersey Shore people were, in fact, pirates, but that their actions had understandable incentives and preventable causes.

There is little question the challenge of reaching a foundering ship in pounding surf during a major winter storm was more than the locals were prepared for. It became clear to many that what was urgently needed were professional surfmen trained and compensated for taking these kinds of risks, provided with facilities, modern equipment, training, and sufficient manpower to be able to respond quickly and effectively when needed.

It’s important to note that even after federal funding was first provided for equipment, the same problems experienced by the wreck-masters of Monmouth County continued. Training was sporadic, equipment was not maintained, staffing levels were rarely optimal, and more lives were needlessly lost. But it is noteworthy that even when managed by dedicated professionals, effecting shore-based rescues was a very daunting challenge, and the harsh judgments made against those who were on hand when the Minturn broke apart would seem to be very unfair.

At the time of the Minturn disaster, the Massachusetts Humane Society had founded the very first lifeboat station, at Cohassett, Massachusetts. These stations were small shed-like structures, holding rescue equipment to be used by volunteers in case of a wreck. In New Jersey, one person who had witnessed such horrifying tragedies was a young doctor living near Barnegat Bay, in the newly created Ocean County. Dr. William A. Newell began to form the idea for dedicated resources, similar to those in Massachusetts, to be deployed in the high-risk area for shipwrecks around Sandy Hook to try and minimize the loss of lives and goods from shipwrecks. When he was elected to Congress to represent New Jersey, Dr. Newell succeeded in getting an amendment added to the appropriations bill that provided $10,000 to build new sheds and equip them with surf boats and other life-saving gear.

The entirety of what eventually became inaccurately known as the “Newell Act” was: “In New Jersey. – For providing surf boat, rockets, carronades, and other necessary apparatus for the better preservation of life and property from shipwreck on the coast of New Jersey, between Sandy Hook and Little Egg Harbor, ten thousand dollars;” It was not an actual act of legislation. But it was a start.

With these funds, the Treasury Department constructed eight lifeboat stations, equipped with galvanized iron surfboats, metal life-cars complete with air chambers and India rubber floats and fenders, and rockets and mortars— along with blue lights, ropes, powder, heating stoves and firewood, lanterns, and shovels. Each station was equipped with a cannon that could shoot a line out to a ship for aiding in rescue efforts. The sheds were erected at five-mile intervals from Sandy Hook to Egg Harbor, in acknowledgment of the severe danger to ships of this stretch of land.

The Newell appropriation is often thought by many to be the official founding of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, but it would be another 30 years before the federal government would formally assume full responsibility for coastal marine rescue and salvage. Over these three decades, the same system of paid wreck-masters appointed by courts for county districts remained in place (Click here to read the Early Legislative History of New Jersey Laws Concerning Wrecks). And this meant that training, staffing, and pay all remained inadequate. Further, there were no funds appropriated for the ongoing maintenance of the life-saving gear that was purchased, and the effects of harsh Atlantic winters and salt water on this equipment led to a steady decrease in the effectiveness of these stations.

The Demise and Legacy of Wreckers

The Federal Wrecking Act on March 3, 1825, mandated that all property shipwrecked in American waters had to be brought to a U.S. port of entry. This ended the longstanding practice of Bahamian wreckers taking U.S. vessels from U.S. waters back to the Bahamas for disposition.

In 1828, the U.S. established a Superior Court in Key West with maritime and admiralty jurisdiction. The only other courts were at St. Augustine and Pensacola, so almost all of the Florida Keys wrecking property was taken to Key West. The wrecking act was further tightened in 1847. Between 1848 and 1858, the Admiralty Court adjudicated 499 wrecks. In 1852 alone, the annual salvage income totaled $1,500,000.

The courts employed 13 rules of wrecking covering collusion, licensing, discrimination, bribery, price fixing, using a disaster to make a profit, wharfage, providing the ship’s master with a copy of rules, rights of the master wrecker, etc. The wrecking ship and its master had to be licensed; its owner’s name only had to be recorded. The ones who prospered were the ship owners and warehouse owners.

The Wrecking License Bureau of the court closed in 1921. The last known licensed wrecker, Captain Chet Alexander, passed away in 1984.

Technology and innovation eventually made wreckers mostly obsolete. New and better lighthouses and lightships made for more reliable navigation aids, with improvements in lenses enabling signals to be seen many miles out at sea. Charts became more standardized and accurate. Insurers made professional pilots available to help ships navigate dangerous passages, and mandated their use. And the advent of steam-powered vessels also gave mariners far greater ability to stay out of trouble during bad weather.

Yet even today, armed with global positioning systems and complex computer-based navigation and communications technology, ships still end up in trouble. If you look at the images captured by the Gibson family of the Scilly Islands, you will see plenty of very modern looking vessels that crashed on the very same rocks as the barks, schooners, sloops, and other sailing vessels from an earlier age. And there are numerous harrowing videos showing that even the most modern vessels are sometimes subject to catastrophe.

Marine salvage remains an industry practiced around the world, nowadays conducted by legitimate companies operating in compliance with maritime laws. They are the last vestiges of a centuries-old tradition that was a real and important part of our history in Monmouth County and other coastal communities around the world.

And there are still wreckers, of a sort. Today, in the Keys, for example, businesses operate to help owners of recreational vessels that have run aground, much like the wreckers that tow automobiles away after an accident. In developing nations, obsolete ships are run right onto beaches where local wreckers then use welding equipment to break up the ship into scrap metal.

Legacy of the Land Pirates of Monmouth County

Between the disasters, accusations, and eventual vindication, the people of Barnegat specifically and Monmouth County in general were reviled as bandits and land pirates. In 1850, the residents of southern Monmouth County voted to create the new Ocean County out of the area south of Manasquan Inlet, a matter that had been in the works for years, to address perceived imbalances in funding and other political considerations. But the taint of banditti would stick to the coastal residents of Monmouth County for many years, until it was embraced and became an odd point of pride. Today, pirates are everywhere in our area. The mascot of Red Bank Regional High School is the Buccaneer. Red Bank once had a semi-pro baseball team called the Pirates. And in Barnegat, where locals once tried desperately to distance themselves from notions of piracy, they now hold an annual Pirates Day celebration of all things buccaneer. And as for wreckers? Once reviled, today they are the salty heroes of a reality TV show called Shipwreck Men.

In the end, despite the heinous accusations, there is no evidence the people of Monmouth County ever tried to lure a ship to its demise, nor that any people aboard wrecked ships were mistreated, dead or alive. But those lurid stories, just like the many myths surrounding pirates, took hold in novels and films – even an opera – and so the facts were ignored, and the legends presented as gospel truth. Myths always sell more tickets or copies. Just a few examples of how public fascination with wreckers translated into popular culture:

- The Allentown Band, as part of a concert program, performed Wrecker’s Daughter, A Quick Step, a classical music piece composed by J.G. Von Rieff in 1840.

- In 1848, two years after investigators exonerated the people of Barnegat, Charles E. Averill authored a popular dime novel called The Wreckers, or, The Ship-Plunderers of Barnegat, a Startling Story of the Mysteries of the Sea-shore, which repeated all of the worst accusations, in fictional form.

- Walt Whitman’s poem about wreckers, “Patroling [sic] Barnegat,” was first published in 1880. The poem was eventually added to the Sea Drift section of his iconic collection of poetry, Leaves of Grass.

- A play written by Scott Marble called Mugg’s Landing, about wreckers in Nantucket, was performed in Monmouth County in 1887.

- Numerous artists, including George Morland, Joseph Mallord, William Turner, Donald MacLeod, Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg, and others, painted dramatic imaginings of wreckers in various parts of the world.

Fictional accounts of wreckers all repeated the three major accusations, along with examples of the worst of their alleged crimes, and helped cement in the public consciousness the notion that the people of Monmouth County, and specifically Barnegat, were the worst of the worst people on earth.

A fairer lasting assessment was offered in the New Jersey Senate’s report on the investigation into the land pirates of Monmouth County:

From the earliest settlement of the state, ever since commerce first began to send her sail along the coast, they have ever stood ready to render every relief and assistance to perishing passengers and crews.

Sources:

An Act Concerning Wrecks. (1821). Laws of the State of New Jersey, Printed by Joseph Justice, 1821, P. 716-723.

A Banditti Discovered. (1835). The Pittsburgh Gazette, Pittsburgh, Penn., January 3, 1835, P. 2.

A Noble-Hearted Wrecker. (1849). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., October 11, 1849, P. 2.

Admiralty Law. (2021). Justia. Available: https://www.justia.com/admiralty/

Amusements. (1856). The New York Times, New York, N.Y., October 15, 1856, P. 6.

Arrest of Squire Platt, the Barnegat (N.J.) Moon Raker. (1837). Boston Post, Boston, Mass., February 16, 1837 P. 2.

Arrived This Forenoon. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., January 12, 1832, P. 2.

Averill, Charles E. (1848). The wreckers, or, The ship-plunderers of Barnegat, a startling story of the mysteries of the sea-shore. F. Gleason, Boston, Mass.

The Banditti Discovered. (1835). Originally published by the New York Courier, reprinted in the Vermont Phoenix, Brattleboro, Vt., January 9, 1837, P. 2.

Bennett, Robert F., Bennett, Susan Leigh, & Dring, Timothy R. (2015). The Deadly Shipwrecks of the Powhattan & the New Era on the Jersey Shore. The History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2015.

Capture of Land Pirates. (1834). The New-York Gazette and Advertiser, New York, N.Y., December 29, 1834, P. 1.

Capture of Land Pirates. (1834). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., December 29, 1834.

Capture of Land Pirates. (1834). The National Gazette, Philadelphia, Penn., December 31, 1834, P. 2.

Capture of Land Pirates. (1834). Sag Harbor Corrector, Sag Harbor, N.Y., December 31, 1834, P. 5. “From the N.Y. Gazette.”

Charles-Town, August 9. (1768). The South Carolina Gazette, Charleston, S.C., August 9, 1768, P. 4.

The Chronometer Found. (1846). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, N.Y., April 24, 1846, P. 2.

Coast Piracies – The Barnegat Pirates. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 26, 1846, P. 2.

Coddington, Ronald S. (2021). Fake News, 1864. The Civil War Monitor, Longport, N.J., Spring 2011, P. 12.

Dreadful Shipwrecks – Disastrous Results of the Storm. (1846). The Somerset Herald, Somerset, Penn., March 3, 1846, P. 2.

Extract of a letter from Antigua, dated April 26. (1789). Poughkeepsie Journal, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., June 16, 1789, P. 3.

Extract of a Letter from Brigthelmstone, Jan. 14. (1746). The Caledonian Mercury, Edinburgh, Scotland, January 24, 1746, P. 3.

Fowles, John. (1975). Shipwreck. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, Mass.

Historical currency converter. (2021). Available: Historicalstatistics.org.

Humanity in New Jersey. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 23, 1846, P. 2.

In Chancery of New Jersey. (1838). Monmouth Inquirer, Freehold, N.J., December 6, 1838.

Interesting Details of the Late Storm – Inhospitality – Barnegat Pirates. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 19, 1846, P. 1.

Graham, David A. (2021). Why Ships Keep Crashing. The Atlantic, March 27, 2021. Available: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/03/ever-given-and-suez-why-ships-keep-crashing/618436/.

The Jersey Pirates. (1846). Public Ledger, Philadelphia, Penn., March 2, 1846, P. 2.

Jerseymen on the Coast. (1854). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., May 25, 1854.

Special Report by the Commissioners to Investigate the Charges Concerning the Wrecks on the Monmouth Coast. (1846). Journal of the Proceedings of the Second Senate of New Jersey, Convened at Trenton, January 30, 1846, P. 588-603. Available: https://www.njstatelib.org/research_library/legal_resources/historical_laws/legislative_journals_and_minutes/.

Lawrence, Iain. (1998). The Wreckers: The High Seas Trilogy, Book 1. Yearling, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, N.Y.

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping. (1890). Lloyd’s Register Wreck Returns, 1st July to 30th September, 1890. November 27, 1890. Available: https://hec.lrfoundation.org.uk/archive-library/casualty-returns

Local News, Gossip, &tc. (1854). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., June 1, 1854, P. 2.

Loss of the ship George Canning. (1832). Washington Globe, Washington, D.C., January 13, 1832, P. 3.

Maloney, E. Burke. (1967). They Lured Vessels Ashore. The Asbury Park Press, Asbury Park, N.J., July 30, 1967, P. 15.

Marine List. (1834). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., September 9, 1834, P. 3.

Means, Dennis R. (1987). A Heavy Sea Running: The Formation of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1846-1878. Prologue Magazine, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Winter 1987, Vol. 19, No. 4. Available: https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1987/winter/us-life-saving-service-1.html#SL4.

Melancholy Shipwrecks. (1846). Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, London, England, March 22, 1846, P. 7.

Memoranda. (1834). The United States Gazette, Philadelphia, Penn., October 18, 1834, P. 4.

Mills, Franklin S. (1856). Of the session of 1856. Legislative Journal of the seventy-second Legislature of the State of New Jersey, containing the debates, proceedings and list of acts of the session, commencing January 8, 1856, P. 64.

Miscellany. (1855). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., January 18, 1855, P. 1.

Nagiewicz, Stephen D. (2016). Hidden History of Maritime New Jersey. The History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2016

The New York Pilots – False Statements Against Them – Their Case. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., March 5, 1846, P. 2.

Newport, June 17. (1765). The Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia Penn., June 27, 1765, P. 2.

Noble, Dennis L. (1994). That Others Might Live: The U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1878-1915. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md, 1994.

Occurrences of the Day, &c. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., February 20, 1832, P. 2.

The Outrages at Squan Beach. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 28, 1846, P. 2.

The Poet’s Corner. (1838). Monmouth Inquirer, Freehold, N.J., February 22, 1838, P. 1.

Port of Philadelphia. (1834). The National Gazette, Philadelphia, Penn., December 2, 1834, P. 2.

Public Acts of the Thirtieth Congress of the United States. (1848). August 14, 1848, P. 114. Available: https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/30th-congress/c30.pdf

Resolutions have been introduced. (1846). Brooklyn Eagle, Brooklyn, N.Y., February 28, 1846, P. 2.

Shepard, Birse. (1961). Lore of the Wreckers. Beacon Press, Boston, Mass., 1961.

Ship George Canning. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., January 13, 1832, P. 2.

Ship News. (1834). The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, S.C., October 30, 1834, P. 2.

Shipwrecks. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., February 3, 1832, P. 2.

Soll, Jacob. (2016). The Long and Brutal History of Fake News. Politico Magazine, December 18, 2016. Available: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/12/fake-news-history-long-violent-214535/

Stranding of the Ship General Putnam. (1832). The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, S.C., February 11, 1832, P. 3.

The Terrible Storm, On Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. (1846). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., February 17, 1846, P. 2.

Timeline 1700’s-1800’s (sic). (2020). United States Coast Guard Historian’s Office. Available: https://www.history.uscg.mil/Complete-Time-Line/Time-Line-1700-1800/.

Uberti, David. (2016). The Real History of Fake News. Columbia Journalism Review, December 15, 2016. Available: https://www.cjr.org/special_report/fake_news_history.php

U.S. District Courts for the Districts of New Jersey: Legislative History. Federal Judicial Center. Available: https://www.fjc.gov/history/courts/u.s.-district-courts-districts-new-jersey-legislative-history.

Whitman, Walt. (1855). Leaves of Grass. Reprinted by The Modern Library, New York, N.Y., 1921.

Woolley, Jerry A. (1995). Point Pleasant. Arcadia Publishing, Dover, N.H., 1995, P. 17.

The Wreckers. (1877). The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, Penn., April 24, 1877, P. 4.

The Wreckers of New Jersey. (1846). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., March 2, 1846, P. 2.

The Wrecks on the Jersey Shore. (1832). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., March 3, 1832, P. 2.

Images:

Wreck of the ship John Minturn, Currier & Ives lithograph. (1846). N. Currier. Created January 1, 1846. Library of Congress. Public Domain.

Pilot’s Monument in Greenwood Cemetery, Currier & Ives. (1857). Created January 1, 1857 by Nathaniel Currier. Public Domain.

Papers of John S. Forman, courtesy Monmouth County Historical Association. Photo by John R. Barrows.

Leave a Reply