June 27 was supposed to be a day of rest, and for most of British Lt. General Sir Henry Clinton’s troops, it was. But for some, it was an opportunity not to be missed, an opportunity for retribution.

General Clinton’s army included many kinds of units in addition to regular British Army redcoats; American Loyalists who were fighting for the king comprised numerous groups. For example, Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe led the Queen’s American Rangers, which included the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of New Jersey Volunteers, as well as Lt. Col. John Van Dyke’s New Jersey Volunteers unit. Clinton’s army also included a unit of 49 freed American slaves called the Black Pioneers who served as woodcutters and bridge builders to help the British make their way across mostly rural central New Jersey.

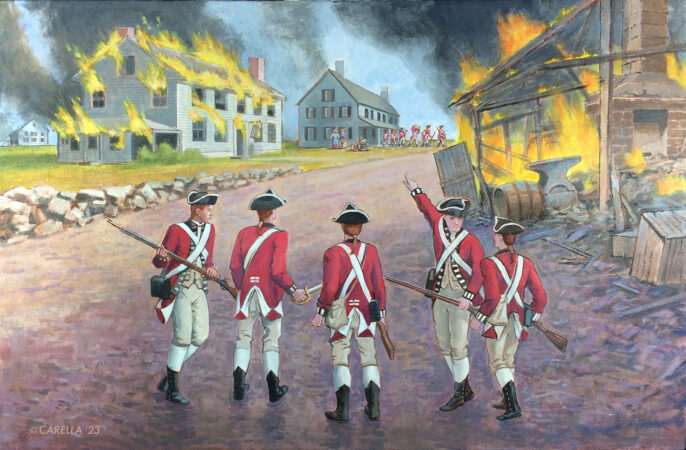

From the start, British Lt. General Henry Clinton insisted on maintaining strict order as his march of more than 20,000 people across New Jersey made its way. He had insisted on knowing ahead of time every woman who would be along on the march, who they were attached to, why they were there, what they could do to pitch in and help. He also issued strict orders prohibiting any looting or stealing from locals along the way. Despite a punishment of immediate death, this order was largely ignored. Now, his army reached Monmouth County, and the Monmouth County Loyalists who were fighting for the king now found themselves with a unique opportunity to exact revenge upon their neighbors and countrymen for having driven them from their homes and depriving them of their property and liberty. Houses and businesses belonging to Patriots were put to the torch; women were raped; livestock and anything usable was confiscated; and fertile planting fields were salted, all in a two-day orgy of cruel and violent vengeance.

The toll of loss would have been much greater, but many Patriot families, knowing the British were headed their way, had fled their homes, driven their livestock into the woods, buried their silver in the ground, or hidden valuables in wells. Some joined up with militia units for protection; some men joined the Continental Army, believing that British soldiers would not harm innocent women and children. This proved to be a disastrous error in judgment, as the harm came not from the British, but primarily from fellow Americans.

British and Hessian generals, including Clinton, professed to be aghast at what occurred, but took no action to stop it. One Hessian officer wrote, “every place here was broken into and plundered by the…soldiers. The church, which was made of wood and had a steeple, was miserably demolished;” the soldiers were “breaking and destroying everything.”

By the end of the 27th, “11 dwellings, assorted outbuildings and at least two businesses had been burned or otherwise destroyed,” according to Mark Edward Lender and Garry Stone Wheeler in Fatal Sunday, their outstanding account of the Battle of Monmouth. Only Patriots had been targeted. Among those who lost everything were the village doctor, the blacksmith, and a tavern keeper. Villagers returning after the battle found “the earth was strewn with dead carcasses, sufficient to have produced a pestilence.”

No other village was sacked during the Revolution in the manner of Monmouth Court House. But after that outrage, the residents of Freehold and the rest of Monmouth County turned up the heat on the escalating civil war in the region. Patriots continued confiscating and selling off Loyalist properties and arresting people without charges, assessing fines, and removing them to prisons in Pennsylvania and Maryland, often solely for their belief that America was better off under crown rule. Loyalists at Sandy Hook, and others hiding in the Pine Barrens, including former slaves such as the infamous Colonel Tye, conducted raids into Monmouth County, arresting militia leaders; stealing guns, food and ammunition; and burning and pillaging homes.

This constant retribution continued until the very end of the Revolution. It did not begin with the Sack of Monmouth Court House, but the events of June 26 and June 27 surely served to significantly escalate the volatility and violence taking place county-wide.

Sources:

Bilby, Joseph G., & Jenkins, Katherine Bilby. (2019). Monmouth Court House: The Battle That Made the American Army. Westholme Publishing, Yardley, Penn.

Fabiano, John, et.al. (2006) A Short History of Allentown. The Allentown Village Initiative, Allentown, N.J Available: https://www.allentownvinj.org/a-short-history.html.

Griffith, William R. (2020). A Handsome Flogging: The Battle of Monmouth, June 28, 1778. Savas Beatie, El Dorado Hills, Calif.

Lender, Mark E., & Stone, Garry W. (2016). Fatal Sunday. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla.

Morrissey, Brendan. (2004). Monmouth Courthouse 1778: The Last Great Battle in the North. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, New York, N.Y.

Smith, Samuel S. (1975). The Battle of Monmouth. Pamphlet published January 1, 1975, New Jersey Historical Commission.

Stryker, William S. (William Scudder). (1970). The Battle of Monmouth. Kennikat Press, Port Washington, N.Y.

Leave a Reply