Monmouth Timeline story by Rick Burton

On Wednesday, January 3, 1703, William Leeds Jr., a wealthy middle-aged Middletown resident, fully drew the mantle of God upon himself as he was baptized as a Christian. The rites of baptism have long been the province of babies and weekends, so, to the locals of Monmouth County, a midweek and fully grown initiate may have seemed unusual. Perhaps this was one reason why residents believed this prominent landowner was seeking to distance himself from rumors his wealth had been acquired through dealings with the notorious pirate, Captain Kidd.

Despite local whispers, it’s more likely Leeds was simply a hard-working, pious man who had inherited a veritable fortune in land from his father, and subsequently invested his capital wisely. Late in life, with much to be thankful for, his baptism may well have reflected nothing more than a commitment to his newfound Anglican faith.

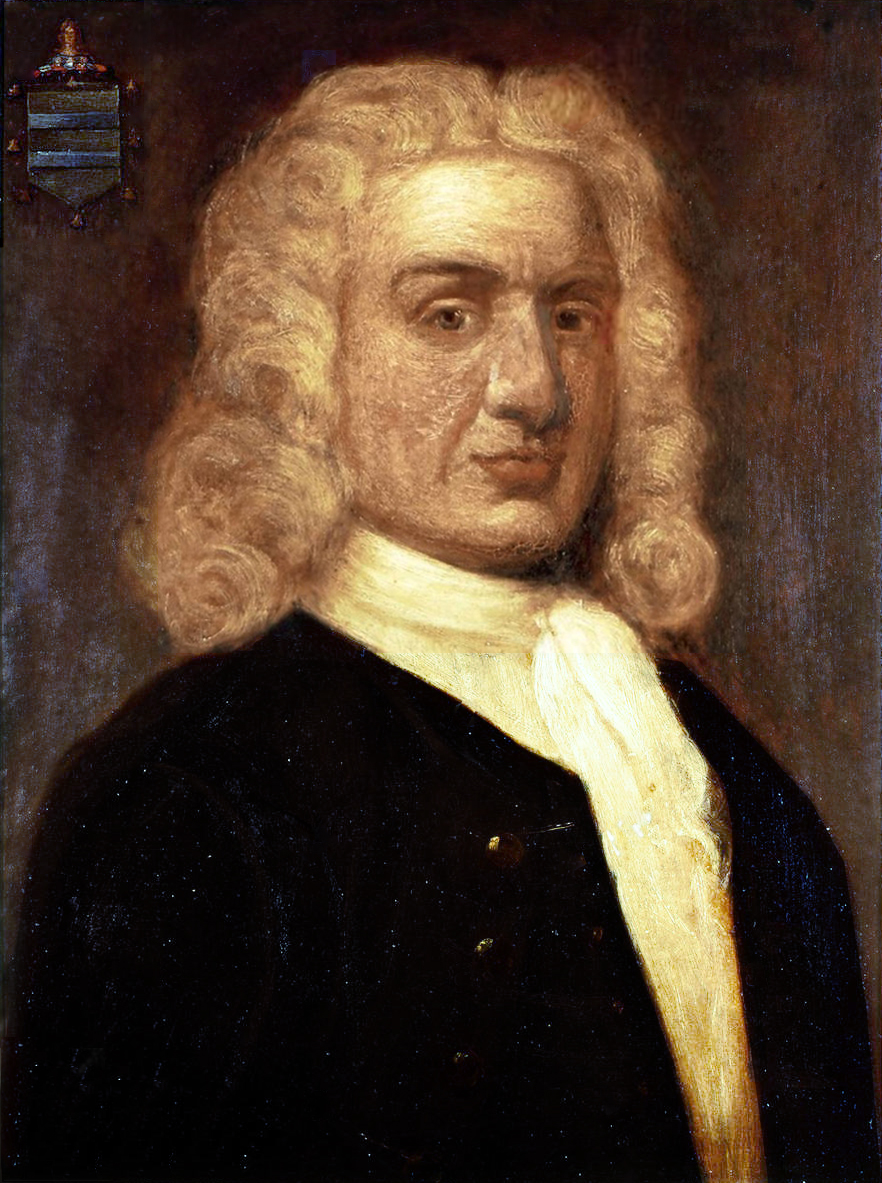

As for William Kidd, three hundred years after his death, historians continue to debate the extent to which he was, in fact, a pirate. Kidd himself, and his crew, during their last years of freedom, all believed fully they had followed their charter and had committed no crimes.

It’s possible both Leeds and Kidd were mostly innocent of accusations made against them. Understanding Leeds’s distinctive Middletown legacy requires consideration of foundational elements of Monmouth County real estate history. As for Kidd, during his years living in New York City, it would have been a very simple matter for him to visit Monmouth County. Local legends say he did, anchoring near Ideal Beach, but there is no evidence to support this. And given his circumstances, there probably would not have been many reasons for him to make such a trip.

This story examines questions about the legacy of William Leeds: Was his wealth attained honestly or was it derived from trading in pirate plunder? Was Leeds actually a “chief cohort” of Captain Kidd the pirate? Did Captain Kidd bury treasure in Monmouth County? Was he ever even here at all? And if none of these things is true, why are they so readily accepted today as fact?

How Did William Leeds Get Rich?

William Leeds Sr. had inherited land in Middletown from his immigrant father, Thomas. He then lawfully acquired additional tracts of land north of the Swimming River in 1679. Five years later, Leeds Sr., and his business partner Daniel Applegate, purchased fields and property in what is today the unincorporated Lincroft community within Middletown Township.

This transaction, in 1684, secured in trade with local Lenape Indians in exchange for heavy woolen fabric (“four yards of Duffels”), or the equivalent value in rum, stipulated annual payment to a tribe member every November 1st until 1999.

In 1694, Leeds Sr. gave 184 acres of land to his eldest son, William Leeds Jr. This property was part of more than 400 acres of desirable Leeds/Applegate farmland bordering Hop Brook. And since William Jr.’s wife, Rebecca, was Daniel Applegate’s widow, by the early 1700s all of the “Leedsville” property was controlled by William Leeds Jr.

This is possibly where the calumny began.

According to the History and Archives of the Trinity Church on Wall Street in Manhattan, William Kidd was:

By many accounts a successful and respected Privateer—that is, a Captain of a private ship that a government could employ to attack foreign vessels during times of war, in part to protect ships of their own and to take enemy vessels and their cargo as prizes. Kidd was even hired by the English on several occasions to do exactly that kind of work.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Raritan Bay was known as an ideal location for sheltering from North Atlantic storms as well as for providing safe mooring for privateers, pirates, and merchant ships alike. The downside of this was that some believed Middletown housed “perhaps the most ignorant and wicked [people] in the world,” a sentiment expressed by none other than Lewis Morris, governor of New Jersey. It is possible this reputation emerged because the village’s early residents were believed to have traded seagoing supplies (food, salt, tar, fresh ropes) with reputable privateers as well as with outlaws, and the spoils of those transactions contributed to the local economy. There were many such places in the original colonies known to be safe havens for pirates, and the profits from trade with privateers were not considered ill-gotten gains. Although trading with pirates was a crime, in the early colonial days people tended to look the other way.

Ill-Gotten Gains or Legitimate Business Transactions?

After Kidd’s death in 1701, Leeds Jr. was seen, unfortunately for him, as one of the wealthiest men in the region, and tavern speculation may have been where whispers started suggesting his wealth had been derived from fencing “silks, Spanish laces, jewels, objects of art and other luxuries” plundered by Kidd the pirate. Some accounts even have Leeds aboard Kidd’s ship as a pirate crew member, although there is no supporting evidence.

The truth of a Leeds-Kidd association may never be known for certain. But from 1691 to 1695, when Kidd was a privateer and merchant captain, Leeds might well have been among Kidd’s active trading partners in New York City. But Kidd had no reason to travel to New Jersey to ply his wares. Through perspicacity, street smarts, and a shrewd marriage to a very wealthy widow, Kidd had become one of New York’s most prosperous residents. All of that had been accomplished without any hint of impropriety.

If Kidd and Leeds knew one another during this time their association would not have tainted Leeds’s legacy, since Kidd was still years away from first being accused of piracy. But, in hindsight, people in Monmouth County likely remembered only that Kidd was a pirate and forgot he was, before that, while in our region, an honest merchant. And so anyone associated with him at any point in time would later be seen as having dealt with a pirate.

Kidd’s path from legitimate merchant to hunted pirate started in 1695 when he decided he wanted to become a captain in the British Royal Navy and left New York City for London in pursuit of that goal. By 1699 Kidd achieved his objective, and was given an assignment to hunt pirates in the Indian Ocean while he also served as a British privateer, allowed to confiscate any vessel flying a French flag. Kidd was helming a new brig, the Adventure Galley, a three-mast, 284-ton (burthen) boat, with 32 cannon, and special ports for using oars when becalmed.

Kidd found difficulty outfitting his ship with experienced crew in New York for the trip to London, and so was forced to bring aboard a number of seamen with dubious pasts, hardened criminals, and pirates.

For this convenience, an error in judgment, Kidd would pay with his life.

As Kidd made his way southward, he came across a small convoy of Royal Navy ships experiencing the worst of oceangoing misfortune. The Navy captain had made several bad decisions and had lost much of his crew to disease and abandonment. Kidd feared the Navy captain would insist on taking Kidd’s crew for his own, and so before sunrise the next morning, Kidd’s men manned oars and silently slipped away into the darkness. The Navy captain was outraged and began spreading rumors Kidd was a pirate. Kidd had yet to fire a shot in anger on this voyage, but reports made their way back to London suggesting he had gone rogue and ventured into a life of crime.

Kidd, oblivious to this, forged his way around Cape Horn and headed for the pirate havens of Madagascar. During this period, many of his crew pressed Kidd to attack ships that were not French, nor pirates, and Kidd reportedly resisted at every turn.

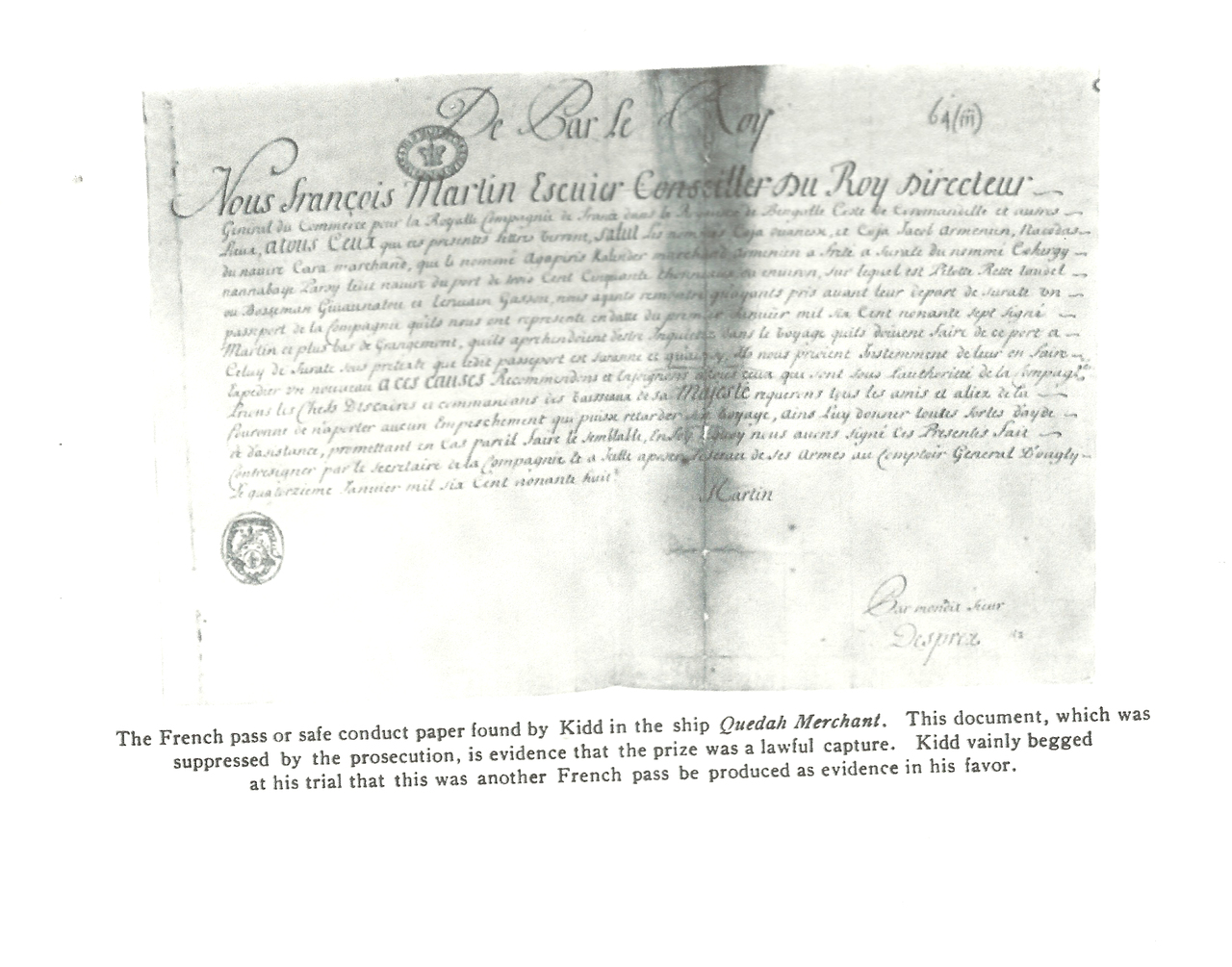

These actions may have made him honorable, but it also made him unpopular with the criminal element among his crew. As he strained to maintain discipline, Kidd finally snapped, and hurled a metal bucket at a recalcitrant crewman, who died from the injury. Ship captains of this era had wide latitude in what they were allowed to do to maintain discipline, but killing was a criminal act. A number of Kidd’s crew mutinied and joined a pirate ship captained by Robert Culliford. They continued to spread rumors at every opportunity that Kidd had turned pirate. Eventually, Kidd did attack and confiscate a vessel operating under French letters of passage. But it wasn’t a French ship. It was Armenian owned and its captain and crew were from India. Yet Kidd and his men believed the documentation they had from the ship validated the seizure.

Kidd returned to the Caribbean from Madagascar in 1699, with a small crew of loyal men and a sizable treasure in gold and silks. Upon arriving, Kidd learned he was perhaps the most wanted criminal in all the world. He decided to head back to New York City. It was in this narrow window, during the months of May and June 1699, that Kidd might have engaged in illicit business dealings as an accused pirate.

Kidd was most certainly in the New Jersey vicinity during this time, making port in Delaware Bay as he returned home. It was there he learned his mutinous crewmen had beaten him back to New York City, having made land at Cape May. Kidd wanted nothing to do with these men, who would almost certainly lodge further accusations against him in an effort to save their own backsides. So he returned to New York City by heading out to sea outside the normal sea lanes and around the tip of Long Island, sailing west along Long Island Sound, and eventually anchoring in Oyster Bay. That approach would have had him sailing northward many miles offshore from Monmouth County, with no reason to take the risk of paying some sort of visit to this area as he sought to evade capture.

Buried Pirate Treasure

Interestingly, it is during this brief time that one of the most legendary pirate stories took root. People have been fascinated by the notion of “buried pirate treasure” for centuries, with myths propagated both in mainstream press and in popular culture. In fact, pirates virtually never did this. Kidd is the only known pirate who buried treasure. He and his men, nervous about possible capture and seizure, offloaded much of their gold and valuables and hid them on Gardiner’s Island, with the help of the island’s owner. Kidd also hid coins and jewels in rolled up hammocks and elsewhere aboard his ship, which also gave rise to the notion his plunder could be found virtually anywhere.

This was because Kidd was avoiding New York City and looking to pursue justice with some of his Boston investors, including his primary sponsor, Richard Coote, 1st Earl of Bellomont. Bellomont was nearly destitute, and fully believing Kidd to be a pirate, intended to extract every last farthing before sending Kidd to the gallows. It is for this reason Bellomont may be largely responsible for the idea Kidd buried treasure elsewhere. Bellomont certainly believed this and sent men and ships looking for Kidd’s loot. But Kidd and his men insisted, from beginning to end, that Gardiner’s Island was the only place they buried treasure. And it was Gardiner himself who dug it all up and dutifully brought it to Bellomont, who of course immediately accused Gardiner of lying and of keeping half or more for himself and sent a crew to the island. Nothing else was ever found.

Thanks to Bellomont and sensationalist newspapers, rumors of Kidd treasure included possible burial sites along Raritan Bay, on Sandy Hook, and elsewhere in Monmouth County. But no legitimate biography or source provides evidence of this, and further, it defies all logic. Kidd had already sailed far past Sandy Hook to avoid detection from ships coming and going from New York City. He had not yet decided to bury anything. And then, he would have had to sail back around Long Island, risking capture, while passing up numerous better hiding places, to bury his loot on Sandy Hook or along the Bayshore.

To be certain, Kidd was a very busy man during the sixty days he spent in the Oyster Bay – Gardiners Island area in 1699. There is no account anywhere suggesting that during this time he continued engaging in business transactions as he had before. By now, he and his wife were broke, and had little with which to trade. His sole focus was on paying off his investors in hopes of attaining his liberty. Therefore, it is highly unlikely William Leeds–and Monmouth County–ever had any interaction of any kind with Kidd during the period when he was accused of piracy.

The Moses Butterworth Saga

Well after Kidd was dead, a member of his crew became the subject of a Monmouth County controversy. Numerous reports reveal a letter composed by John Johnstone, the former presiding judge of the Monmouth Court, to the New Jersey Council. On March 26, 1701, Johnstone wrote that during a trial involving one of Kidd’s men, a Middletown militia of 70-80 men forced their way into the courthouse and “being in arms, forcibly rescued the prisoner,” a man named Moses Butterworth.

Johnstone further added that the militia’s ringleaders were known to harbor Butterworth, an admitted Kidd crew member, and threatened harm to anyone seeking to remove him. As Mark Hanna wrote in Humanities (2017)

Jailbreaks and riots in support of alleged pirates were common throughout the British Empire during the late seventeenth century. Local political leaders openly protected men who committed acts of piracy against powers that were nominally allied or at peace with England. In large part, these leaders were protecting their own hides: Colonists wanted to prevent depositions proving that they had harbored pirates or purchased their goods.

There were other reasons why residents of Middletown may have looked the other way and assisted privateers, pirates, and marauders, even if none of them was named Kidd. As Hanna noted,

Many colonists feared that crackdowns on piracy masked darker intentions to impose royal authority, set up admiralty courts without juries of one’s peers, or even force the establishment of the Anglican Church. Openly helping a pirate escape jail was also a way of protesting policies that interfered with the trade in bullion, slaves, and luxury items such as silk and calico from the Indian Ocean.

Eventually escaping from New Jersey, Butterworth made his way to pirate-friendly Newport, R.I., and in 1704 purchased his own ship, having obtained a charter to chase down Royal Navy deserters. But the Moses Butterworth saga helped further cement in people’s minds the notion that Monmouth County, and especially Middletown, was pirate country.

William Leeds stayed put, clearly not concerned about rumors of having been a pirate or associate, and transferred his allegiance (or faith) from possibly having broken bread with Captain Kidd to receiving it from Reverend George Keith, who preached at Christ Church Middletown’s first recorded service on June 17, 1702.

So taken was Leeds with Keith and his new faith that church records show on January 3, 1703, Leeds and his sister, Mary, “late converts from Quakerism,” were baptized by Keith into the Church of England at Middletown. Due in large part to Keith’s success (and financial backing from Leeds) Middletown was recognized as having established one of the first churches in New Jersey.

Leeds died in 1739 and was originally buried “near his house in Swimming River” in Lincroft, but was thereafter removed and relocated to the Christ Church cemetery in Shrewsbury, a sacred place he had helped establish.

How Captain Kidd and William Leeds Jr. Found Religion

In July 1699, Kidd was tricked by Lord Bellomont, and captured in Boston. Held for more than a year, he was eventually extradited to England and found guilty by the Crown for the murder of the crewman struck by a metal bucket. He was hanged on Execution Dock in London on May 23, 1701, and, to visibly discourage others from piracy, gibbeted over the Thames River at Tilbury Point.

That might have been the end of the story, with nothing left but the writing of books like Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883), or the production of swashbuckling movies like 1935’s Captain Blood with Errol Flynn. More recent narratives have tended to paint pirates as broad caricatures, like Johnny Depp’s portrayal of Captain Jack Sparrow in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies. None of these accounts has much basis in fact in terms of how pirates really lived, but helped fuel our society’s endless fascination with buccaneers.

But perhaps counter-intuitively, violent seagoing captains, at least in the form of Kidd, could also embrace religion.

No less an authority than the iconic Trinity (Episcopal) Church in Lower Manhattan provides the following from their Archives about Kidd and Christianity: “A fascinating and, perhaps, misunderstood character of history, Kidd is often associated with sea piracy and allegedly burying treasure in the Caribbean in the later parts of the 17th century.” But it was Kidd who agreed to lend Trinity a hand with the construction of the first Trinity Church. This Scottish-born seaman helped build Trinity’s first church building when it was agreed on July 20, 1696, in the minutes of The Vestry of Trinity Church that: “Capt. Kidd has lent a Runner & Tackle for the hoiseing [sic] up Stones as long as he stays here.” The runner and tackle borrowed from Captain Kidd would have been a pulley system, of sorts, allowing workers to lift heavy stones during construction.

And, before making his final voyage, Kidd appears to have made a sizable donation to the church by renting a pew with the church’s rector that was still servicing his heirs as of 1718, 17 years after his death.

In a similar vein, 29 years after his baptism, Leeds Jr. donated land that ultimately helped endow the rector’s salary at Christ Protestant Episcopal Church on Kings Highway in Middletown, the first Episcopal church in Monmouth County.

It is unlikely William Kidd was ever devout in his embrace of Christianity. His endowment of Trinity Church may have been out of a desire to achieve respectability and entrée into higher social circles. Likewise, while Leeds Jr. may have come by his wealth entirely honestly, by the time of his baptism the world had come to consider Kidd a bloodthirsty criminal and people refused to believe Leeds had not been his chief cohort. So, his own finding of religion late in life may have been as much a survival strategy as an expression of piety. This, we can never truly know.

And while Trinity Church in New York City is the source of some of what we know about Kidd, the Christ Church of Middletown is responsible for popularizing the legends surrounding Kidd and Leeds that some still treat as gospel truth to this day.

How Legends Become Accepted Truth

In 1927, Christ Church of Middletown was preparing to celebrate its 225th anniversary. As a part of that celebration, the church published a book by Christ Church Rector Ernest W. Mandeville called “The Story of Middletown: The Oldest Settlement in New Jersey.” Mandeville was described in a Red Bank newspaper as being “a regular contributor to…’The New Republic,’ ‘Time,’ and other national magazines.”

Mandeville appears to have been something of a reluctant historian. In his forward, he notes that “THE WRITER of this Story of Middletown does not claim originality.” He cites a number of familiar historians of this region, e.g., Edwin Salter, Franklin Ellis, and others. He also warns that “He [the writer] does not claim over diligent research, but he covered as much ground as was possible in the press of time for publication and the limitations of expense imposed upon him.”

He was apparently asked to do a rush job on the cheap. Perhaps it’s no wonder he finished the forward with, “He looks forward to the time when ancient Middletown can have a more worthy historian.”

The book is a compendium of history and folklore, that is, what some might call myth, but the two are conflated throughout. The title claim is a good example of how this book can be confusing to unpack.

Is Middletown in fact “the oldest settlement in New Jersey?” Mandeville makes this claim in two ways. Of the Lenape tribes, the aboriginal inhabitants of this region, he states that “These early owners of Middletown claimed they were the most ancient of all aboriginal nations.”

The claim is not attributed. But in the Notes, the author states that the “oldest settlement” claim is due to a Middletown resident, Thomas Whitlock, having been the first person in New Jersey to receive a recorded deed, and on that basis, making him “the first N.J. settler of record under the English.” That happened in 1664. But Camden (1626) and Jersey City (1630) are both much older, and several other communities in New Jersey were settled the same year as Middletown.

From that dubious and confusing start, Mr. Mandeville eventually presents a chapter on “Pirate Days in Middletown.” In it, he makes a number of wholly unsubstantiated statements such as, “There is sufficient historical data to make positive the fact that many of Captain Kidd’s pirate crew did spend considerable time in Middletown and its environs.” This is a reference to Moses Butterworth, but that story is given separate treatment elsewhere, and so this could be interpreted as referring to other Kidd crew members. The Moses Butterworth event actually happened, but we are unable to find evidence anyone else from Kidd’s crew was ever in Middletown.

And while Mandeville tries to clarify it was Kidd’s men who had a connection to Middletown, not Kidd himself, he at the same time appears to originate the claim that Leeds was a “chief cohort” of Kidd’s. There is no recorded use of the phrase “chief cohort” prior to Mandeville’s book…but it will be repeated and presented as established fact thereafter.

In 1999, as just one example, a story in the Asbury Park Press included the following: “History looks favorably upon William Leeds, from what is now Lincroft, even though this lifelong resident of Monmouth County was known to be one of Kidd’s chief cohorts.” From myth to fact.

Mandeville’s claim that members of Kidd’s pirate crew came to be residents of Middletown was said to have been confirmed by one “Don Seitz.” We believe this is a reference to Don Carlos Seitz, a newspaperman and author, who wrote a seminal book of pirate stories called Under the Black Flag: Exploits of the Most Notorious Pirates.

But this book makes only this bare mention with respect to its retelling of Kidd’s tale: “…he [Kidd] approached his home port cautiously. Some of the men went ashore on the Jersey coast and made themselves scarce. With the others he put into Peconic Bay…”

A person can choose to interpret “the Jersey coast” as Monmouth County, but the event remains highly unlikely. It’s important to remember that the channel through which all shipping bound for or departing from New York City ran very close to the tip of Sandy Hook, which is why there were so many shipwrecks in that area, and why it was chosen for one of the first lighthouses in North America. Kidd would have known sailing anywhere near Monmouth County was taking a higher risk of being spotted and being apprehended. The comings and goings of vessels at the turn of the 18th century was a matter of high interest to a great many people, and so ships did not move about anonymously. Sooner or later, if he passed by enough other vessels, someone was going to recognize Kidd, or figure out the wanted pirate had returned.

Mandeville was clearly repeating what he had seen in 19th century newspapers, such as the Brooklyn Star and the Monmouth Democrat (Freehold), that seemed to almost never pass up an opportunity to give air to a spurious pirate story. For example, if a rusty pistol was found…it must be Kidd’s! Kidd buried treasure in Connecticut, somewhere “up the Mystic River.” Money diggers in Poughkeepsie. A cannon was raised from the Hudson River near Stony Point and “It is expected that all of Captain Kidd’s money will be found in this vessel, and that it will be got up in the course of a few days.” An unidentified body found on Coney Island “is probably one of Captain Kidd’s men, left to take care of the pirate’s treasures.” A Monmouth farmer digs up an iron kettle, it must contain Kidd’s gold! Alas, only dirt. And yet, a kettle of found dirt was deemed by a newspaper publisher as being worthy of inclusion in his newspaper. In 1873, the Monmouth Democrat reported “Captain Kidd’s particular trunk has been dug up again at Cape May, with untold wealth therein.” Their use of “again” here seems sardonic.

Possibly the most egregious example of pirate fiction posting as fact in newspapers is a page-one story from The Monmouth Democrat in 1877. Under the headline, “Capt. Kidd and his Gold,” the story has six breathless sub-headlines: “Great Excitement at Ocean Beach.” “Digging for the Long Hidden Treasure.” “The Money Chest Discovered,” and so on. The story relates at great length an Indian legend about four white men in a canoe who buried bags of treasure on a hill near the beach south of Barnegat. The four men murdered a Black man and buried him with the treasure, so as to guard it.

The story continues for almost two full columns. But it ends with an absurd notion that treasure hunters finally did see a chest, but then found that “lo! it had disappeared because it was Satan’s treasure.” And nothing was ever found. The article is signed “Capt. Kidd.” It is complete fiction, but only those who read all the way to the very end would know this. Scant wonder these sorts of fictions would take hold as fact.

It is important to note that newspapers of this era regularly blended fact and fiction, for various reasons. Sometimes it was a matter of repeating an erroneous story published elsewhere, not knowing it was untrue. Sometimes, a story was just too good to pass up when there was a newspaper to fill and there was money to be made.

This was common practice in the days preceding the Civil War; you had all sorts of “newspapers” that blurred fiction and non-fiction, news and entertainment. Remember all the entertainment people had in those days was what they read. This was popularized in the 1830s with the “penny press,” a way to get the working class to read newspapers.

Joel Kaplan Ph.D.

Associate Dean for Professional Graduate Studies

Newhouse School, Syracuse University

An examination of newspaper coverage of Captain Kidd in New York and New Jersey from 1700-1845 shows almost anything could be tied to Kidd and presented as established fact. In addition, beginning in the mid-19th century, Kidd and other famous pirates become the subject of new books, plays, and sketches. The public fascination (and commercial business) with pirates of yore was in full swing.

In Monmouth County, legends of Kidd’s treasure being buried near Barnegat in an area that became known as “Money Hill” were repeated in various forms. The Camden Morning Post ran a story in 1877 declaring that Ocean Beach (now known as Belmar) was becoming a winter attraction due to ongoing attempts to find Kidd’s gold. “There are mysterious comings and goings and dark hints of iron chests and unfamiliar coins. Nobody seems to be willing to acknowledge the finding of anything, but everyone suspects his neighbor of more knowledge than he shares.”

James A. Bradley, founder of the Monmouth County towns of Asbury Park and Bradley Beach, claimed in a promotional pamphlet that Kidd buried treasure on the dunes in the area. It seems everyone wanted to have a connection to Kidd.

Mandeville’s book and the Christ Church anniversary celebration in 1927 helped usher in a new round of fictive pirate stories, and no less an authority than The New York Times repeated these as gospel in 1935. Their take was that “bloodshed and crime of more than two centuries ago now pay the salary of the rector of Christ Protestant Episcopal Church at Middletown.” The Times story unquestioningly repeated Mandeville’s assertions that Leeds was one of Kidd’s “chief cohorts,” and his gift to the church was out of guilt, remorse, and a desire for atonement.

And so it goes. As recently as 2020, a publisher of history books came out with a new edition repeating Mandeville’s claims about Kidd and Leeds without attribution, sources, or new evidence of any kind. Perpetuating myths sells books. But, the legacy of William Leeds Jr., and possibly even that of William Kidd, deserves a more truthful telling.

Our cultural obsession with pirates is such that many people simply want to believe stories more fantastic than factual. All over Monmouth County (and New Jersey) there are references to pirates of various sorts that have very little basis in fact.

Today, all across Monmouth County, pirates are a celebrated part of the culture. For example, the Red Bank Regional High School mascot is the Buccaneer; Red Bank once had a semi-pro baseball team called the Pirates. While being smeared as being in cahoots with pirates was once something to be avoided at all costs, modern citizens seem to embrace all things pirate as though the crimes committed by them were as fictional as so many other aspects of buccaneer lore.

There were indeed actual pirates who operated in and around Monmouth County, but they are obscure figures with relatively unknown names. We believe Kidd and Leeds may have been associated before Kidd’s accused piracy, but Leeds’s fortune was not tainted by ill-gotten gains. How pious they really were cannot be known, but their contributions in establishing and supporting houses of organized worship created lasting legacies.

Rick Burton is the David B. Falk Professor of Sport Management at Syracuse University.

Sources:

All Sorts of Items. (1873). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., February 6, 1873, P. 1.

Captain Kidd. (1837). The Long-Island Star, Brooklyn, N.Y., April 27, 1837.

Capt. Kidd and his Gold. (1877). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., January 18, 1877, P. 1.

Captain Kidd and His Treasures. (1844). Buffalo Courier, Buffalo, N.Y., July 12, 1844, P. 1.

Cheslow, Jerry. (1995). If You’re Thinking of Living In: Middletown Township, N.J.; A Historic Community on Raritan Bay. The New York Times, December 24, 1995, Section 9, P. 3. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/1995/12/24/realestate/if-you-re-thinking-living-middletown-township-nj-historic-community-raritan-bay.html?searchResultPosition=4

Christ Church of Shrewsbury Now 225 Years Old. (1927). Asbury Park Press, October 22, 1927, P 1, 3.

Coffee for every body — Pistol for one. (1831). The Evening Post, New York, N.Y., July 26, 1831.

Cushing, Luther S., & Dixon, S.F., editors. (1842). Captain Kidd. American Jurist and Law Magazine for April and July, 1842, Vol. XXVII, P. 347-363. Charles C. Little and James Brown, Boston, Mass.

DeNicola, Linda. (2011). The Truth About Christ Church: A Legacy of Piracy in Middletown. Community Corner, Patch, March 11, 2011. Available: https://patch.com/new-jersey/middletown-nj/saving-souls-with-ill-gotten-gains-in-middletown

Early History of Middletown. (1928). The Daily Standard, Red Bank, N.J., January 20, 1928, P. 3.

From the Archives. (2016). Captain Kidd Lends Runner & Tackle for Building First Trinity Church. Trinity Church Wall Street, July 15, 2016. Available: https://www.trinitywallstreet.org/blogs/archives/captain-kidd-lends-runner-tackle-building-first-trinity-church

Geffken, R., and Smith, M.J. (2019). Hidden History of Monmouth County, The History Press, Charleston, S.C.

Hanna, Mark G. (2017). A Lot of What Is Known about Pirates Is Not True, and a Lot of What Is True Is Not Known. Humanities, National Endowment for the Humanities, Winter 2017, Volume 38, No. 1. Available: https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2017/winter/feature/lot-what-known-about-pirates-not-true-and-lot-what-true-not-known

Harbour, Glenn. (1999). The pirates of Middletown. Asbury Park Press, June 7, 1999, P. 1.

Irwin, Dean. (2012). Captains, Pirates and Ghosts. Secrets of New York, WNYC-TV, November 2, 2012. Available: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/media/shows/secrets-of-new-york.page?id=1870?pg=5

Kaplan, Joel. (2021). “RE: Seeking an expert on the history of U.S. newspapers.” Message to Rick Burton and John Barrows, April 23, 2021. E-mail.

Leeds Was Not A Pirate. (1897). The Monmouth Press, Atlantic Highlands, November 27, 1897, P. 1.

Mandeville, Ernest W. (1927). The story of Middletown: The oldest settlement in New Jersey. Christ Church, Middletown, N.J., January 1, 1927.

Memories of Captain Kidd Still Haunt Shore. (1961). Asbury Park Press, January 29, 1961, P. 5.

The Money Diggers. (1840). New York Daily Herald, New York, N.Y., January 10, 1840, P. 2.

A Monmouth Farmer in Luck. (1871). Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., November 23, 1871, P. 2.

The Mysterious Body Found at Coney Island. (1845). Brooklyn Evening Star, Brooklyn, N.Y., September 1, 1845, P. 2.

Ocean Beach. (1877). The Morning Post, Camden, N.J., January 25, 1877.

One of the Iron Guns. (1844). Brooklyn Evening Star, June 10, 1844, P. 2.

Searcher, Selah. (1872). Gov. Parker’s Historical Address. Monmouth Democrat, Freehold, N.J., June 6, 1872, P. 2.

Seitz, Don C. (1925). Under the Black Flag: Exploits of the Most Notorious Pirates. Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, New York.

Zacks, Richard. (2002). The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd. Hyperion. New York, N.Y.

Featured image credit: Captain Kidd in New York Harbor by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Pirate Relaxing by Howard Pyle , Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: The Pirates Own Book, by Charles Ellms, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: The Book of Buried Treasure by Ralph Delahaye Paine, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply