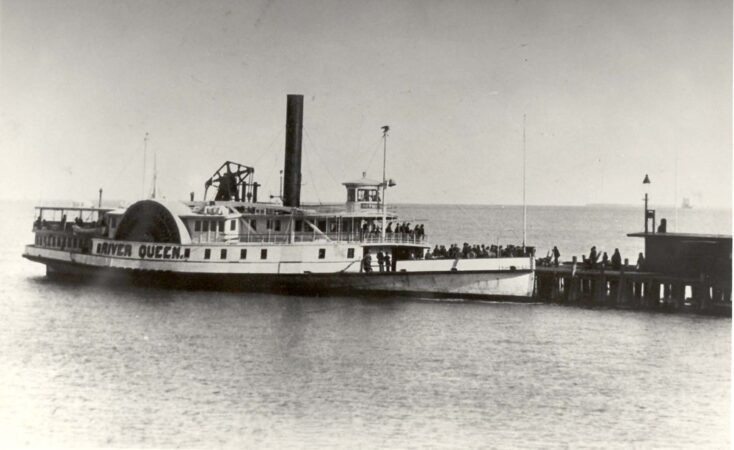

On March 31, 1864, the steamship SS River Queen, one of numerous side paddlewheel steam-powered vessels built in Monmouth County in the years prior to the Civil War, was launched by Benjamin C. Terry in Keyport. When launched, the River Queen was the largest vessels to come out of Keyport, 181 feet in length with 536 tons displacement, and only one other, the SS Seawanhaka, would ever be built bigger locally.

The River Queen was built for Alfred Van Santvoord, a wealthy American businessman who made his fortune running steamboat lines. It originally saw service carrying passengers between Providence and Newport, R.I. In December of 1864, she was “chartered to the [U.S.] Army Quartermaster Department at New York for $241 per day for a period of thirty days and as long thereafter as her services were required.”

The ship, now the USS River Queen, was valued at the time of the Army charter at $145,500, about $2.5 million today. She was sent to Fort Monroe, Va., and used as a troop transport and then carried supplies to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters at the junction of the James and Appomattox Rivers. She served as Union Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s headquarters for a time, then as Gen. Grant’s dispatch boat.

During this era, a “dispatch boat” was a vessel that carried messages, or mail – called dispatches – between high-ranking military officials aboard other ships or ashore. Large numbers of dispatch boats, such as USS Massasoit, USS Gladiolus and USS Geranium among others, were used during the Civil War, especially by the Union. Gen. Grant depended on dispatch boats during his Virginia campaign to correspond with Union Navy ships on the James River.

The Hampton Roads Conference

As the war’s end became imminent, representatives of the Confederacy planned to travel to a neutral location to negotiate peace terms with U.S. Secretary of State William Seward. Grant needed a suitable vessel to accommodate such meetings. The Army quartermaster, in recommending the River Queen, wrote: “This boat is almost new, is built in the most substantial manner, is very fast and powerful and well adapted for a dispatch boat.”

On January 31, 1865, three Confederate commissioners: Alexander Stephens, C.S.A. vice president of the Confederacy; John A. Campbell, secretary of war; and Robert M.T. Hunter, senator, made their way toward the battle lines around Petersburg, Va., in a carriage under a flag of truce. After careful negotiation with Union leaders, the three were eventually allowed to cross. A remarkable scene occurred when the Confederate commissioners passed through the lines. Fighting ceased and troops on both sides came out of their trenches and bomb-proofs, cheered loudly and shouted lustily, “Peace! Peace!”

The trio made their way through the Union lines and eventually boarded the River Queen to meet with Seward. Discussions began on February 1.

Grant felt that Lincoln had to be involved as certain questions arose that could only be decided at the highest level of authority. On February 3, Lincoln joined what became known as the Hampton Roads Conference for four hours of discussions that ultimately failed to accomplish anything. The two sides still had very different viewpoints about ending hostilities. While inconclusive, the meeting was helpful to Lincoln and his leadership in steeling their resolve that any end to the war had to entail restoration of the union, and an end to slavery. They now also understood this would only happen after the surrender of the Confederate armed forces.

Lincoln’s Final War Summit

On March 27, 1865, Lincoln held a strategy session by his Union high command on the River Queen to discuss how best to press their campaign to a victorious conclusion. Present were Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, Grant and Lincoln. It was the first and only time Lincoln and Sherman met.

In the war’s waning hours, Lincoln and his family moved onto the ship to await news of the impending surrender. On April 9, the River Queen returned the president and his family to the capitol. Before Lincoln retired that night, he learned that C.S.A. General in Chief Robert E. Lee had surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. This was the last time Lincoln would be aboard the Queen; he was assassinated five days later.

New President Andrew Johnson, for various reasons, chose not to use the River Queen as a presidential yacht. On October 30, 1865, her charter was allowed to expire, and she was returned to her owners. She saw passenger service on the Potomac, and then, in 1868, the once-again SS River Queen returned to the waters of her birth, running passengers between Spermaceti Cove on Sandy Hook and New York City for the Long Branch & Sea Shore Railroad.

After changing hands, the Queen offered passenger excursions between Newburgh, N.Y., on the Hudson River, and New York City. Shortly thereafter, she was chartered to ferry passengers between Woods Hole and Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., for the New Bedford, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Steamboat Company. That company eventually purchased the ship in 1874 and opened a new Hyannis–Nantucket route. That summer, now-President Grant heard that the ship he had come to love was running this new service and brought his family to Cape Cod on vacation for a trip aboard the familiar vessel. Once again, the fabled ship made national news.

After about 18 years running passengers along Nantucket Sound, the River Queen was moved back to another familiar locale, the Potomac, running passenger excursions to Mount Vernon, Va.

Despite enormous interest in the ship’s historic role during the Civil War, it was sold in 1898, converted into a barge, and finally registered as a total loss following a spectacular fire that lit up the wharf in Washington D.C., with the wreck later sold as junk. The SS River Queen had served with great distinction for 47 years.

Sources:

Alfred Van Santvoord Dies on his Yacht. (1901). The New York Times, July 21, 1901, P. 5.

Harris, William C. (2000). The Hampton Roads Peace Conference: A Final Test of Lincoln’s Presidential Leadership. Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. Volume 21, Issue 1, Winter 2000, P. 30-61. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0021.104

Reussille, Leon (1975). Steam Vessels Built in Old Monmouth 1841 – 1894. J. I. Farley Printing Service, Inc., Brick Township, N.J., P. 111-116.

Webster, Ian. (2013). Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator. Available: https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1864?amount=145500

Leave a Reply