The early life-saving stations from Sandy Hook to Egg Harbor were for the use of paid officers called “commissioners of wrecks,” or “wreck-master,” who were responsible for leading and coordinating marine rescue and salvage efforts. These men received about $200 a year, and if one discovered a vessel in distress he had to collect a crew to assist him. State law provided for payment for these helpers, and penalties for those who refused, but most of those who did respond did so voluntarily, such was the minimal nature of the pay. (Click here to read An Early Legislative History of New Jersey State Laws Concerning Wrecks). A wreck-master might have to hike for miles before he could get a crew together, and perhaps by the time they reached the station, the vessel would be broken up and all hands lost. There was no central organization or management, and no inspection system to insure that men and equipment were up to standards.

And yet, these men succeeded time and again in effecting incredible rescues under the most daunting circumstances.

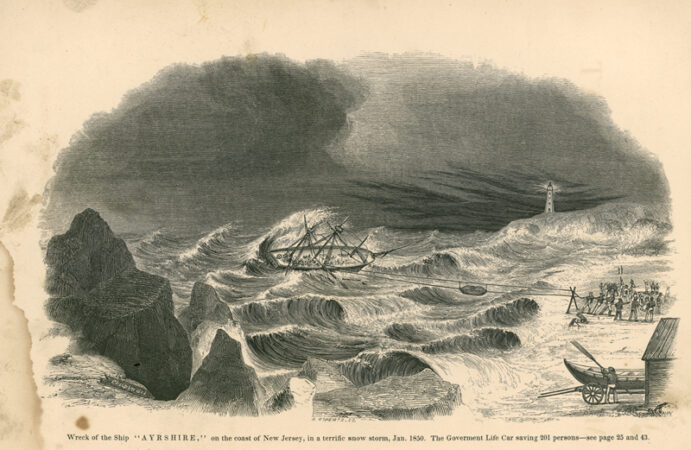

On New Year’s Day, 1850, two years after the federal funding of the life-saving stations, the Scottish bark Ayrshire ran aground on a sandbar off Absecon Island, in Atlantic County. Winds from the furious storm soon tore the sails from her spars, dismasted the ship and disabled the rudder. Eventually, the storm subsided, and the Ayrshire was blown free of the sandbar, but, unable to navigate, drifted at the mercy of winds and current for twelve days, traveling some 50 miles northward. The ship was getting closer to shore, but blinding snow made visibility almost impossible. Those on shore could hear the anguished cries of those who were just beyond reach. The Ayrshire finally breached off Squan Beach and turned over on her side in the surf.

One passenger later described seeing a flash from shore, and suddenly a heavy rope flew over the ship. The seas being too rough for surfboats, Commissioner of Wrecks John Maxson was eager to try out their new Francis Life-Car. Over the next two days, Maxson and his crew of volunteers on shore rescued 201 people aboard the doomed ship, with only one death, from a young man who panicked and tried to jump on top of the Life-Car, but was blown into the sea and drowned.

The amazing success of the rescue of the Ayrshire quickly prompted Congress to allocate additional funds to build more life-saving stations, extending to Cape May. The Francis Life-Car used in the Ayrshire rescue was donated and is on exhibit at the Smithsonian Institute. Another Francis Life-Car is on display at the museum at the Twin Lights of Navesink in Highlands.

The system of stations languished until 1871 when Sumner Increase Kimball was appointed chief of the Treasury Department’s Revenue Marine Division. One of his first acts was to send Captain John Faunce of the Revenue Marine Service on an inspection tour of the lifesaving stations. Captain Faunce’s report noted that “apparatus was rusty for want of care and some of it ruined.”

Kimball convinced Congress to appropriate $200,000 to operate the stations and to allow the Secretary of the Treasury to employ full-time crews for the stations. Kimball instituted six-man boat crews at all stations, built new stations, and drew up regulations with standards of performance for crew members.

By 1874, stations were added along the coast of Maine, Cape Cod, the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and Port Aransas, Texas. The next year, more stations were added to serve the Great Lakes and the Houses of Refuge in Florida. In 1878, the network of lifesaving stations were formally organized as a separate agency of the United States Department of the Treasury, called the U.S. Life-Saving Service.

Sources:

Bennett, Robert F., Bennett, Susan Leigh, & Dring, Timothy R. (2015). The Deadly Shipwrecks of the Powhattan & the New Era on the Jersey Shore. The History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2015.

‘Timeline 1700’s-1800’s (sic). (2020). United States Coast Guard Historian’s Office. Available: https://www.history.uscg.mil/Complete-Time-Line/Time-Line-1700-1800/

Means, Dennis R. (1987). A Heavy Sea Running: The Formation of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1846-1878. Prologue Magazine, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Winter 1987, Vol. 19, No. 4. Available: https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1987/winter/us-life-saving-service-1.html#SL4

Public Acts of the Thirtieth Congress of the United States. (1848) August 14, 1848, P. 114. Available: https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/30th-congress/c30.pdf

Noble, Dennis L. (1994). That Others Might Live: The U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1878-1915. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1994.

https://americanhistory.si.edu/onthewater/collection/TR_160322.html

Image source: https://americanhistory.si.edu/on-the-water/maritime-nation/shipwrecks/wreck-rescue-immigrant-ship (artist and publication not known)

Leave a Reply